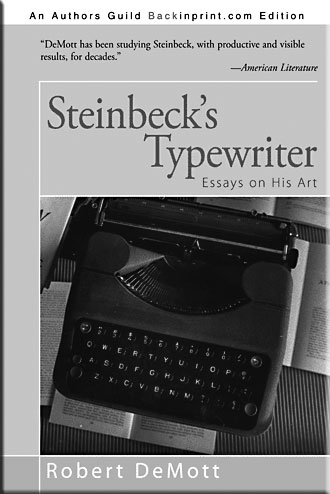

Among the great novels, John Steinbeck books, and artifacts on view at the Center for Steinbeck Studies sits the elegant Hermes typewriter Steinbeck used in Travels with Charley, its surface etched by Steinbeck with the enigmatic phrase: “THE BEAST WITHIN.” It’s there thanks to Robert DeMott, the author of numerous John Steinbeck books and articles and arguably the most original writer about the great novels of John Steinbeck alive today. As the 75th anniversary of the The Grapes of Wrath approaches, Bob is the ideal guide for readers of John Steinbeck books who have lost their emotional connection with the great novels, including The Grapes of Wrath. To recover your lost chord with Steinbeck, go to Steinbeck’s Typewriter by Bob DeMott. This superb collection of essays on The Grapes of Wrath and other John Steinbeck books, first published in 1996, was recently reissued in paperback as An Authors Guild Backinprint.com Edition. Take your time when you read it. Even the footnotes are fascinating.

Among the great novels, John Steinbeck books, and artifacts on view at the Center for Steinbeck Studies sits the elegant Hermes typewriter Steinbeck used in Travels with Charley, its surface etched by Steinbeck with the enigmatic phrase: “THE BEAST WITHIN.” It’s there thanks to Robert DeMott, the author of numerous John Steinbeck books and articles and arguably the most original writer about the great novels of John Steinbeck alive today. As the 75th anniversary of the The Grapes of Wrath approaches, Bob is the ideal guide for readers of John Steinbeck books who have lost their emotional connection with the great novels, including The Grapes of Wrath. To recover your lost chord with Steinbeck, go to Steinbeck’s Typewriter by Bob DeMott. This superb collection of essays on The Grapes of Wrath and other John Steinbeck books, first published in 1996, was recently reissued in paperback as An Authors Guild Backinprint.com Edition. Take your time when you read it. Even the footnotes are fascinating.

The Story Behind a Trio of John Steinbeck Books

In his introduction Bob notes that Steinbeck’s Typewriter completes the trilogy of John Steinbeck books he began with Steinbeck’s Reading (out of print but available on the Steinbeck Studies Center website) and Working Days: The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1989 and in print ever since. In a joyful anecdote, Bob explains how he acquired Steinbeck’s typewriter for the Steinbeck Studies Center—along with rare editions of John Steinbeck books, manuscripts, and family memorabilia—while serving as acting director and visiting professor of English at San Jose State University, almost 30 years ago. He tells the story as if it happened yesterday, and its impact still feels fresh. “In my moment of obsessive identification,” he says, “the diminutive machine came alive as a cumulative metaphor for the entire complex of Steinbeck’s working life. . . .”

In my moment of obsessive identification, the diminutive machine came alive as a cumulative metaphor for the entire complex of Steinbeck’s working life.

As this episode suggests, Bob’s approach to the great novels of John Steinbeck is direct, existential, and engaged. Propelled by passion and supported by research, the essays in Steinbeck’s Typewriter are academic in only narrowest sense the word. Instead, as Bob admits, they are “intensely personal, by which I mean they either echo thematic resonances in my own life”—a level of participation in John Steinbeck books that the author of The Grapes of Wrath invited his readers to discover when his books were first read. With astonishing depth and prodigious detail, Bob maps the structure, philosophy, and language of each of the great novels—The Grapes of Wrath, To a God Unknown, East of Eden, and The Winter of Our Discontent—discussed in Steinbeck’s Typewriter. His side excursions are equally compelling—into Steinbeck’s poetry, Steinbeck criticism, and the manuscript mysteries behind The Grapes of Wrath, East of Eden, and The Winter of Our Discontent.

Language and Politics in the Great Novels

An examination of the second draft of The Winter of Our Discontent, for example, “shows that the final thirteen pages of the novel were not in the autograph manuscript but were added by Steinbeck . . . .” A Steinbeck ledger, also studied by Bob at the Pierpont Morgan Library, reveals that Steinbeck planned to write a play-novel on the Cain-Abel theme used in East of Eden as early as 1946, the year his second son was born. The first draft of The Grapes of Wrath helps explain how the greatest of the great novels by Steinbeck was finished so quickly: “When he was hot,” as he was with The Grapes of Wrath, “Steinbeck wrote fast, paying little or no attention to proper spelling, punctuation, or paragraphing.” The typescript of the novel submitted to Steinbeck’s editor reveals that the four-letter words the writer was forced to remove before publication were the usual suspects—with the exception of a six-letter epithet still applied to unpleasant overweight cops.

When he was hot, Steinbeck wrote fast, paying little or no attention to proper spelling, punctuation, or paragraphing.

But Steinbeck’s Typewriter is more than a detective story about manuscripts or a bibliography of John Steinbeck books. In nine substantial essays it explores aspects of background, language, character, and thought encountered in the great novels from To a God Unknown to The Winter of Our Discontent. The echoes of Robinson Jeffers heard in the language of To a God Unknown are amplified by scanning lines from the novel as poetry. The “gruesome experiences, including rape and murder” of Steinbeck’s paternal grandparents in 19th century Palestine “throw some starling new light on East of Eden’s characters.” The Grapes of Wrath is analyzed as a “huge symphony of language,” written while Steinbeck actually listened to Bach, Tchaikovsky, and Stravinsky—with a note that Steinbeck claimed “Edgar Varese the modern composer wants to do [a work] based on one of my books. I wrote him that I thought Grapes might be a theme for a symphony. . . .” The continued relevance of Steinbeck’s protest against “tyranny of surveillance, arrogance of power, and willful destruction of people and resources” in The Grapes of Wrath is underscored by a reminder that Steinbeck’s title was subversive when it was chosen, despite the veneer of patriotism applied after the fact.

A Guide to Greater Participation in John Steinbeck Books

Since 1969 Bob has taught the great novels of John Steinbeck and other American writers at Ohio University, where he is Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor of English. It’s a remarkable record of achievement and stability. But as a student in the 1960s Bob says he was lost—until reading John Steinbeck books for the first time changed his life for good. “I had almost no direction at all,” he explains. “My life took a marked turn after my first exposure to Steinbeck’s writing. I gained a second chance, which is one way of defining a writer’s gifted appeal and power. . . .” In Steinbeck’s Typewriter Bob suggests how participating in the great novels of Steinbeck is still possible for readers who feel lost in their lives. True, Bob was prepared by circumstance to enter the world of John Steinbeck books with more ease than some. He was born to Italian-American parents and, until he was 8, lived on the estate of Arthur Szyk, a celebrated Polish-American artist with Jewish roots and outspoken views. Today Bob writes poetry, fly fishes with expertise, and lists the monumental Library of America edition of John Steinbeck books among his academic accomplishments. Not everyone has such a resume.

My life took a marked turn after my first exposure to Steinbeck’s writing. I gained a second chance, which is one way of defining a writer’s gifted appeal and power.

Like the great novels of Steinbeck, however, Steinbeck’s Typewriter displays few signs of distance from the experience of ordinary readers. Quite the opposite. Each essay conveys an aspect of Bob’s palpable affection—for John Steinbeck books, for fellow Steinbeck critics, for the class of Steinbeck students who comprise his imagined audience. Most of all he loves Steinbeck’s characters, empathizing with their struggles and understanding them, as the author intended, in every element of their condition. Here is what he dares to write about the notorious ending of The Grapes of Wrath: “This prophetic final tableau scene—often condemned and misunderstood, but for that no less subversively erotic, mysteriously indeterminate—refuses to fade from view; before the apocalypse occurs, before everything is lost in forgetfulness, Steinbeck suggests, all gestures must pass from self to world, from thought to word, from desperateness to acceptance, from participation to communion.” Bob DeMott’s typewriter, like Steinbeck’s, is an instrument of grace—a means of understanding, a mode of deliverance, a way to participate more fully in life through reading. Use it.

Love the story of Steinbeck’s typewriter and nostalgia associated with the manufacturer’s name. I remember the Hermes that was provided for my first (and only) typing class, all under the tutelage of a heavyset, merry nun, who advised me to give it up. My final score was something like 34 wpm with 28 errors.

Fortunate for all there are avid scholars of Steinbeck, like DeMott and Ray, who keep the works of this literary genius alive and relevant to today’s readers. Thanks for the marvelous read!

Here are some quotations from John Steinbeck about typewriters:

There was delivered to me as a gift an Olivetti typewriter in a case of beautiful polished blond leather with a design in gold – one of the handsomest things I have ever seen.

– Louisville Courier-Journal, “Steinbeck in Italy”, Florence. 4/28/57,

–

The enclosed is written not on the new typewriter which I have ordered but on one loaned by IBM until the new one can be delivered. The new one has larger and prettier type but this one is a demonstrator machine.

– Letters to Elizabeth. [New York City] [11/23/57], p. 85

–

A typewriter stands between me and the word, a tool that has never become an appendage, but a pencil is almost like an umbilical connection between me and the borning letters.

– Steinbeck: A Life in Letters. Elia Kazan, 4/1/59, 624,Discove Cottage

Fascinating! Thank you, Herb. (For readers unfamiliar with the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, Herb Behrens is the Center’s senior archivist. When separating fact from fiction about Steinbeck and his hometown, no one is more knowledgeable, accessible, or accurate that Herb.)