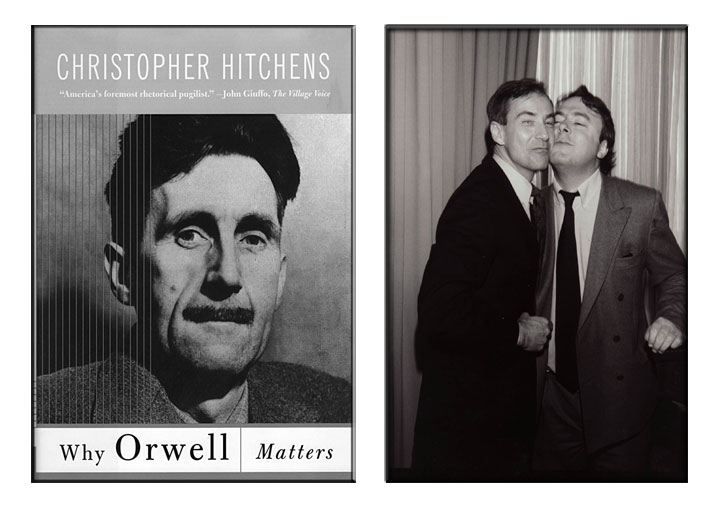

When Winston Churchill described the Soviet Union as dropping an Iron Curtain across Central Europe his speech to an American audience in 1946, George Orwell was living in London and imagining a future England under a Stalinist dictator. From Orwell’s paranoia about the Soviet Union came his masterpiece 1984. A less fortunate outcome was a set of accusatory, argumentative letters, diaries, and notebooks produced during the four years of Orwell’s remaining life, including a list of 100 or more suspected “crypto-communists” such as John Steinbeck. The late author Christopher Hitchens, Orwell’s intellectual heir and ardent defender, provided insights into the writer’s mindset in Why Orwell Matters, a convincing argument for Orwell’s continued relevance, despite lapses of judgment like the paranoid list. My friend Christopher Hitchens died in 2011. I regret now that I never asked him about Orwell’s list while he was alive.

When Winston Churchill described the Soviet Union as dropping an Iron Curtain across Central Europe his speech to an American audience in 1946, George Orwell was living in London and imagining a future England under a Stalinist dictator. From Orwell’s paranoia about the Soviet Union came his masterpiece 1984. A less fortunate outcome was a set of accusatory, argumentative letters, diaries, and notebooks produced during the four years of Orwell’s remaining life, including a list of 100 or more suspected “crypto-communists” such as John Steinbeck. The late author Christopher Hitchens, Orwell’s intellectual heir and ardent defender, provided insights into the writer’s mindset in Why Orwell Matters, a convincing argument for Orwell’s continued relevance, despite lapses of judgment like the paranoid list. My friend Christopher Hitchens died in 2011. I regret now that I never asked him about Orwell’s list while he was alive.

Why Christopher Hitchens Matters

I met Christopher Hitchens while moderating a debate about socialism during the dying days of the old Soviet Union. The Iron Curtain was falling throughout Europe, and the debate organizer explained that the challenging case for socialism would be made by Christopher Hitchens, an English-born journalist whose name was new to me. Trained in political debate at Cambridge, Christopher Hitchens rarely lost an argument on any subject that engaged his interest, including democracy movements behind the Iron Curtain, post-Soviet Union U.S. politics, and the questionable existence of God. I learned this in the course of a friendship that lasted until his much too early death.

Like Orwell, Christopher Hitchens was a master of irony, irreverence, and oxymoron. A loyal friend, he was relentless in print but respectful in person. Like Orwell, he remained faithful to his early socialist ideals while criticizing communism as it developed in the Soviet Union and its Iron Curtain satellites. He shared a tough, pared-down liberalism with Orwell and (I believe) with Steinbeck as well. Its basic principles (in my own words) are relevant to the case of Orwell vs. Steinbeck:

The Seven Laws of Liberalism

* Freedom is precious.

* Truth is objective.

* Reason is essential.

* Every individual has value.

* No authority is infallible.

* God is debatable.

* History happened.

Ten Questions for Christopher Hitchens

Liberal ideals inform everything Christopher Hitchens wrote, including his short book about Orwell. I find the same values in Steinbeck, a writer of fiction less partisan or politically sophisticated than either Englishman. Orwell accused Steinbeck of favoring the Soviet Union over democracy, and neither Hitchens nor Orwell acknowledged Steinbeck’s characteristically American liberalism. In compensation for their failure, here are the questions I would ask Christopher Hitchens, Orwell’s finest defender, if I still had the chance :

1. Like Steinbeck, Orwell was a religious skeptic who clung to the King James Bible and echoed liturgical language in the cadence of his prose. Like Steinbeck, Orwell requested and received a Church of England funeral. What should we make of this paradox in the behavior of these profoundly lapsed Anglicans?

2. Like Steinbeck, Orwell was an empiricist who preferred evidence over theory and was once described as having too much common sense to be interested in philosophy. Yet Steinbeck’s thinking about teleology and group behavior reflect similar ideas in Orwell’s social writing. What meaning can we take from this coincidence in the thinking of these covert philosophers?

Orwell was an empiricist who preferred evidence over theory and was once described as having too much common sense to be interested in philosophy.

3. Like Steinbeck, Orwell was an anti-imperialist democrat who distrusted centralized power. This position was well-established in both writers by 1943, when each was in London. Yet I find no record that they met when they had the opportunity. What conclusion can be drawn from Orwell and Steinbeck’s failure to connect?

4. In your book you describe Orwell as “a natural Tory.” Like Steinbeck, he held old-fashioned ideas about private ownership, self-sufficiency, and family loyalty absorbed from his upbringing in a small rural town. Yet both writers remained pro-labor, small-d democrats throughout their lives. What can be inferred from this inconsistency of liberal and conservative values?

Like Steinbeck, Orwell was an anti-imperialist democrat who distrusted centralized power.

5. Unlike Steinbeck, Orwell never visited the Soviet Union. In your book you explain that Orwell “never went through a phase of Russophilia or Stalin-worship or fellow-travelling.” What conclusions can we draw from Orwell’s distant opposition to the Soviet Union and his reaction to Steinbeck’s journey behind the Iron Curtain?

6. Like Steinbeck in Vietnam, you supported America’s invasion of a foreign country, and you became an American citizen in an act of solidarity with the administration of George Bush. Unlike you, Orwell disliked America and Americans, including Steinbeck. Yet he never visited the America. What motivated Orwell’s animosity-from-a-distance toward the United States?

Orwell never went through a phase of Russophilia or Stalin-worship or fellow-travelling.

7. Unlike Orwell, Steinbeck resisted criticizing other writers in print. Orwell publicly denigrated American regionalists like Steinbeck as reactionaries by definition, and he disparaged Steinbeck’s work in his private writing. What motivated Orwell’s public criticism and private doubts about John Steinbeck?

8. Orwell’s Cold War list of “crypto-communists” included pro-Soviet Union American politicians such as Henry A. Wallace and Claude Pepper, despite their anti-imperialist, pro-labor domestic positions (also Steinbeck’s). Was there more to Orwell’s suspicions about these politicians than their support for the Soviet Union?

Unlike Orwell, Steinbeck resisted criticizing other writers in print.

9. Besides Steinbeck, Wallace, and Pepper, Orwell’s list included Charlie Chaplin, Paul Robeson, and Orson Welles. Yet each shared Orwell’s distrust of reactionary media moguls like Citizen Cain—William Randolph Hearst. Why did Orwell single out Steinbeck, Robeson, and Welles in his list of Iron Curtain sympathizers wihtin the United States?

10. Like Steinbeck, Orwell was deeply attracted to the ficton of Jack London, whose 1906 novel The Iron Heel—like Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World—clearly influenced the writing of 1984. Yet Steinbeck’s 1942 anti-fascist piece, The Moon Is Down, apparently lacked similar appeal for Orwell. In your book you note that Orwell lashed out at other writers—including Huxley—but apologized after the fact. Did Orwell have similar second thoughts about Steinbeck before he died?

How the Soviet Union Became Orwell’s Obsession

Christopher Hitchens notes that while working for the BBC, Orwell included “the grittier work of James T. Farrell, John Steinbeck, and Archibald MacLeish” in a radio program about new writers. Orwell’s scripts were scrutinized by BBC censors to avoid offending listeners, and his on-air words didn’t always reflect his real opinion. This was clearly the case with his views on Steinbeck, who is described in Orwell’s diary as a “spurious writer” and “pseudo-naif.” Unfortunately, Steinbeck is only one example of Orwell’s muddled opinions about literary quality. In a notorious case of poor judgment, he publicly criticized W.H. Auden’s “September 1, 1939” for lack of authenticity, credibility, or accuracy in its description of the Spanish Civil War. Today Auden’s anti-fascist masterpiece is considered by many his greatest poem.

Steinbeck is described in Orwell’s diary as a spurious writer and pseudo-naif.

Orwell’s public muttering about Auden provides another clue to his disapproval of Steinbeck. Like Aldous Huxley before him (and Christopher Hitchens years later), Auden emigrated to the United States, arriving in 1939 with the English writer Christopher Isherwood. Like Huxley and Hitchens, Auden and Isherwood were attracted by certain American freedoms—including sex—not found in England. Unlike Christopher Hitchens and George Orwell, both Auden and Isherwood were gay—card-carrying members of the “pansy left” publicly disparaged by Orwell. Orwell’s anti-American bias and anti-gay prejudice combined in his attack on Auden. In the case of Steinbeck, “anti-Soviet Union anti-Americanism” appears to have been sufficient cause for censure.

Why Christopher Hitchens’ Defense of Orwell Falls Short

In Why Orwell Matters, Christopher Hitchens defends Orwell’s list of “crypto-communists” as a harmless intellectual exercise, a game of “guessing which public figures would, or would not, sell out in the event of an invasion or a dictatorship.” He surmises that Orwell’s conservatism about sex in general and gay sex in particular was the result of Orwell’s boyhood experience as a student at St. Cyprian’s, a Dickensian hellhole where bullying, beating, and buggery were routine. But Orwell went on to Eton, where he perfected his French under Aldous Huxley and began his lifelong friendship Cyril Connolly, an openly ambisextrous editor who proved helpful to his career.

Christopher Hitchens defends Orwell’s list of crypto-communists as a harmless intellectual exercise, a game of guessing which public figures would, or would not, sell out in the event of an invasion of a dictatorship.

In the end, Christopher Hitchens’ argument fails to exculpate Orwell. Of Orwell’s “crypto-communists,” he explains that “while a few on ‘the list’ were known personally to Orwell, most were not,” concluding that Orwell’s charge against people he didn’t know didn’t make him a “snitch.” Illiberal, inconsistent, and unconvincing. The world of 1984 is crawling with snitches whose testimony leads to torture and death at the hands of Big Brother. Every individual has value, truth is objective, and history happens. Orwell showed his list naming Steinbeck to influential friends, one of whom worked for an agency of government with the Orwellian name “Information Research Department.”

I agree with Christopher Hitchens that George Orwell still matters. But not always for the right reason. Unlike my late friend, Orwell was prejudiced against gays, Americans, and anyone he suspected of sympathy with the Soviet Union. Though if he hadn’t attacked Steinbeck, even that might not matter.