When I first read Travels with Charley in Search of America—Steinbeck’s nonfiction account of his 1960 road trip from his grandparents’ John-Knox New England to the Salinas Valley of his youth—I was researching the author’s religious roots for an article. Steinbeck’s assertion in Travels with Charley that he attended services one Sunday at a “John Knox church” and liked what he heard didn’t fit what I’d learned about the author’s life or writing. John Knox, the founder of Presbyterianism in Scotland, was a rigid, unyielding Calvinist—a type deeply unloved by Steinbeck, as exemplified in the stiff-necked, self-righteous character of Liza Hamilton in East of Eden. The easygoing Episcopalian religion that permeates The Winter of Our Discontent, written in the same period as Travels with Charley, more accurately reflects Steinbeck’s upbringing. Olive Steinbeck abandoned the Scots-Irish, John Knox atmosphere of the Hamilton ranch for St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Salinas, where her son imbibed the cultured air of candles, flowers, and English church music. What event provoked Steinbeck’s John Knox epiphany in the pages of Travels with Charley? My sources were clueless.

When I first read Travels with Charley in Search of America—Steinbeck’s nonfiction account of his 1960 road trip from his grandparents’ John-Knox New England to the Salinas Valley of his youth—I was researching the author’s religious roots for an article. Steinbeck’s assertion in Travels with Charley that he attended services one Sunday at a “John Knox church” and liked what he heard didn’t fit what I’d learned about the author’s life or writing. John Knox, the founder of Presbyterianism in Scotland, was a rigid, unyielding Calvinist—a type deeply unloved by Steinbeck, as exemplified in the stiff-necked, self-righteous character of Liza Hamilton in East of Eden. The easygoing Episcopalian religion that permeates The Winter of Our Discontent, written in the same period as Travels with Charley, more accurately reflects Steinbeck’s upbringing. Olive Steinbeck abandoned the Scots-Irish, John Knox atmosphere of the Hamilton ranch for St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Salinas, where her son imbibed the cultured air of candles, flowers, and English church music. What event provoked Steinbeck’s John Knox epiphany in the pages of Travels with Charley? My sources were clueless.

Help with the John Knox Problem in Travels with Charley

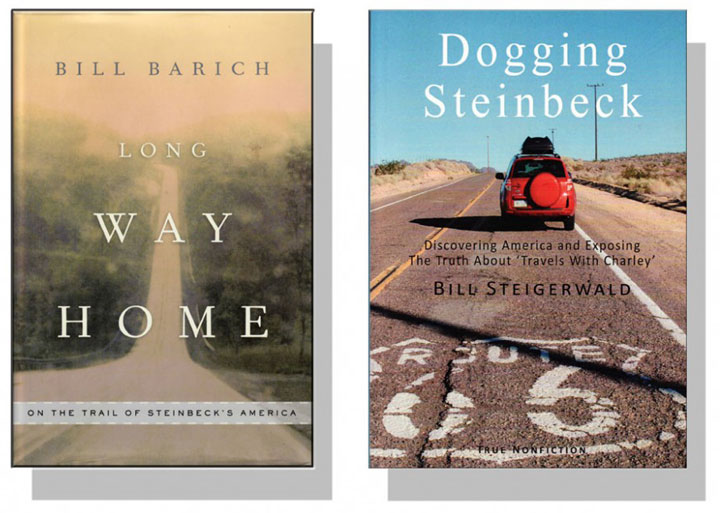

Then I read a pair of books by two non-academic writers that suggest why this detail—and others—didn’t seem quite right when I read Travels with Charley. Except for their common subject, the books couldn’t be less alike. Bill Barich, the author of Long Way Home: On the Trail of Steinbeck’s America, is a California native whose earlier book—Big Dreams: Into the Heart of California—helped me acclimate to my adopted state when I arrived in 2007. A part-time Californian with a second home in Ireland, Barich possesses an elegant style, a Marin County manner, and an inborn appreciation for California’s liberal culture and laid-back lifestyle. Bill Steigerwald, the author of Dogging Steinbeck: Discovering America and Exposing the Truth About Travels with Charley, is Barich’s opposite—a tough-minded Middle-American reporter with little love for liberalism or laying back. Barich and Steigerwald’s books retracing Travels with Charley differ dramatically, reflecting their authors’ contrasting temperaments, assumptions, and aims. Both are worth reading, and each helped me adjust to the probability that Travels with Charley is only partially true.

Barich and Steigerwald’s books retracing Steinbeck’s journey differ dramatically, reflecting their authors’ contrasting temperaments, assumptions, and aims.

Barich retraced portions of Steinbeck’s 1960 election-year Travels with Charley tour during the presidential year of 2008, when the Obama-McCain campaign divided Americans generally along Kennedy-Nixon lines. I happen to share Barich’s enthusiasm for Obama and his respect for Steinbeck’s progressive politics. The author was a lifelong FDR Democrat, despite his family’s John Knox, Teddy Roosevelt Republican roots. He wrote speeches for Stevenson’s 1956 campaign against Eisenhower and supported Kennedy against Nixon in 1960. The pages of Travels with Charley are full of liberal-minded sentiments, underdog characters, and conversations about current issues that aren’t always recognizable as the way real people talk. This, of course, is where Bill Steigerwald comes in. He thinks Travels with Charley belongs in the category of fiction. My reasons for partially agreeing with him are quite personal.

Personal Questions About Travels with Charley Characters

When my mother was pregnant, my dad was still in the Army at Fort Hood, Texas. A proud North Carolinian, Mom insisted on returning to Winston-Salem before my birth because, as she later explained, “I wasn’t about to have my first youngin’ born in Texas.” Perhaps that genetic prejudice produced my doubts about Steinbeck’s sincerity in praising the virtues of his Texas hosts—friends of his Texan-born wife, Elaine—on display during Thanksgiving Day dinner in Travels with Charley. As an ex-New Orleanian, I was also challenged by the tidy trio of Louisiana conversationalists encountered by Steinbeck in the climactic episode of Travels with Charley, a horrific hate-fest observed outside a recently desegregated New Orleans school. Steinbeck’s screaming racist mothers belong to a recognizable segregationist type. But none of the individuals he talks with about the issue of integration sounds to my ears like a Southerner, a Louisianian, or a living human being. Other characters present similar problems. These are the few I sensed were phony from my own experience.

None of the individuals Steinbeck talks with about the issue of integration sounds to my ears like a Southerner, a Louisianian, or a living human being.

Politically, Bill Steigerwald is no John Steinbeck, Bill Barich, or Will Ray. A crusty contrarian with a chip on his shoulder about big government of either party, he wrote Dogging Steinbeck during the Tea Party election of 2010, managing a kind word for Sarah Palin while deconstructing Steinbeck’s 50-year-old classic. It seems unlikely that anyone reading this blog isn’t familiar with the controversy created by Steigerwald in his argument from fact to reclassify Travels with Charley as fiction. Unlike Barich, he retraced Steinbeck’s route and schedule as closely as he could. Unlike Barich’s sentimental journey, Steigerwald’s road trip was gritty, gumshoe detective work. Skeptical by nature and by profession, Steigerwald looked for inaccuracies and found them. He couldn’t locate the “John Knox church” Steinbeck claimed to visit, doing the math to prove that Steinbeck’s published schedule made a Sunday morning church service of any kind unlikely the day Steinbeck says he got a dose of his grandmother’s John Knox religion.

Read Steigerwald’s book or visit his website. He’s a John Knox kind of journalist—hardnosed, relentless, and unfazed by criticism from what he describes as the “West Coast Steinbeck Industrial Complex.” I predict we’ll be hearing more from him about the shades of partial truth he uncovered in Travels with Charley.

[…] and Bill Barich’s book about Travels with Charley (also shown in photo), by reading “Shades of Partial Truth in Travels with Charley“ at […]