Why did George Orwell put John Steinbeck’s name on the list of “crypto-communists” he kept in his notebook while writing 1984, his Cold War classic about totalitarian England under a Stalinesque Big Brother? As the troubled alliance between the USSR and the Free World collapsed following World War II, confirming Orwell’s deepest doubts and deadliest anxieties about Stalinist dictatorship, Steinbeck was living alone in California, dealing with personal depression, divorce, and the death of Ed Ricketts, while Orwell worked frantically to finish 1984 on a remote island in Scotland, filling his notebook with the names of public figures he considered potential collaborators in the Stalinist invasion he feared. Why was the author of The Grapes of Wrath, Bombs Away, and The Moon Is Down among those suspected by Orwell of being fifth-columnists for the communist cause in England and the United States?

Why did George Orwell put John Steinbeck’s name on the list of “crypto-communists” he kept in his notebook while writing 1984, his Cold War classic about totalitarian England under a Stalinesque Big Brother? As the troubled alliance between the USSR and the Free World collapsed following World War II, confirming Orwell’s deepest doubts and deadliest anxieties about Stalinist dictatorship, Steinbeck was living alone in California, dealing with personal depression, divorce, and the death of Ed Ricketts, while Orwell worked frantically to finish 1984 on a remote island in Scotland, filling his notebook with the names of public figures he considered potential collaborators in the Stalinist invasion he feared. Why was the author of The Grapes of Wrath, Bombs Away, and The Moon Is Down among those suspected by Orwell of being fifth-columnists for the communist cause in England and the United States?

Parallel Lives for Two World War Writers

In their personal lives and political views Orwell and Steinbeck weren’t so different, despite Orwell’s distinct Englishness and Steinbeck’s individualistic Americanism. Born too late to fight in World War I, their paths could have converged in London during the darkest days of World War II, though a meeting was unlikely for reasons that will become clear. As adults who came to age following World War I, each writer defied family expectations, rejected their Anglican faith, and dropped out of school to gain real-life experience for their writing among working class people during the turbulent period between 1919 and 1939. Both became pro-labor leftists in the 1930s and attempted, without success, to enlist in active service when World War II began. Both did their part in the world war against fascism using their best weapon—words.

Like George Orwell, John Steinbeck was an urban liberal activist with small-town conservative roots.

Like George Orwell, John Steinbeck was an urban liberal activist with small-town conservative roots. As a Stanford student following World War I, he witnessed America’s Big Red Scare, when hysteria about Bolsheviks, blacks, and labor unions created what Frederick Lewis Allen called a “reign of terror” by the federal government and local vigilante groups. When Red-Scare tactics were employed against Steinbeck following The Grapes of Wrath, the writer complained to the Roosevelt administration, incurring the wrath of J. Edgar Hoover, director of Roosevelt’s newly named Federal Bureau of Investigation. In post-World War II America, Steinbeck’s celebrated liberalism remained part of the public image of California’s famous pro-democracy writer. Yet George Orwell—a communist-inspired socialist with political views left of Steinbeck’s—accused Steinbeck of being the communist when the Cold War began. What change caused this charge?

Dangerous Developments in Post-World War II Events

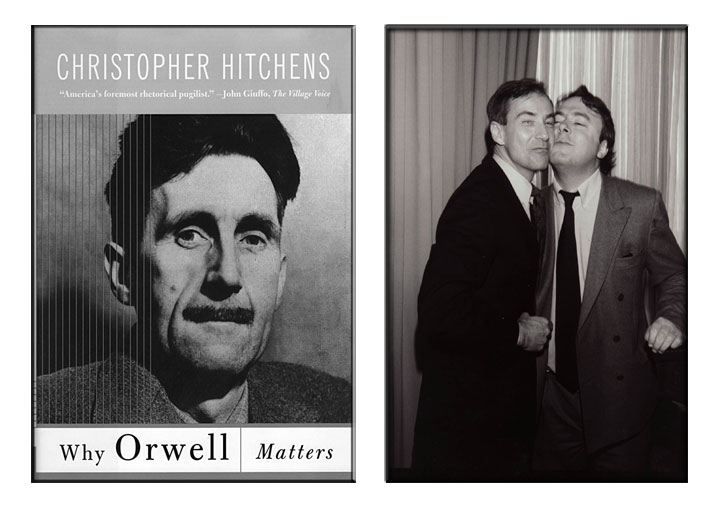

George Orwell certainly understood the potential consequences of his Cold War list of “crypo-communists.” Wounded in 1937 while fighting with English volunteers against Franco’s fascists, Orwell was better educated and more experienced in European politics than Steinbeck, an American democrat who denied ever being a socialist or an –ist of any kind. Betrayed by Stalinist spies embedded in the anti-Franco coalition, Orwell barely escaped from Spain with his life. Who new better than Orwell the cost of being secretly accused by former comrades of taking the wrong side in an internecine struggle for partisan dominance? If Orwell’s list of suspected communists became public when the Cold War turned hot, as Orwell anticipated, those he named —including Steinbeck—could be expected to pay a price.

If Orwell’s list of suspected communists became public when the Cold War turned hot, as Orwell anticipated, those he named —including Steinbeck—could be expected to pay a price.

Why did George Orwell accuse John Steinbeck of sympathizing with Cold War Stalinism despite his own experience 10 years earlier? Part of the answer can be explained by certain elements of Orwell’s peculiar personality—extreme partisanship, English parochialism, and literary pique. As a professional book reviewer, Orwell disparaged American writing, including Steinbeck’s. His English pride was hurt by America’s rising dominance following World War I and Roosevelt’s treatment of Churchill in the closing days of World War II. His political partisanship led to paranoid illusions about the motives of opponents, particularly those within his own party. But there were more likely American writers for George Orwell accuse of being fifth-columnists for communism in the United States. What did he chose Steinbeck, whom he probably never met? Armchair psychology and what-if history aren’t always helpful, but a bit of both is required to answer this under-asked question.

Pre-World War I Babies; Pre-World War II Adults

George Orwell and John Steinbeck were born within a year of one another, middle-class children of dominant mothers and distant fathers who displayed an early aptitude to act out for the benefit of family and friends. As a boys both were bright, independent, and inventive—indulged by doting mothers and by sisters with whom they remained close. Like Orwell, Steinbeck grew up in domestic security, surrounded by hills and fields and the animals he loved. A restless college dropout, Steinbeck bummed his way to New York to haul cement and work as a reporter after digging ditches and picking crops back home. Like Steinbeck, Orwell was restless in school. Bored by life at Eton, his failure to study nixed his chances for the scholarship to Oxford or Cambridge his parents expected him to win. Enlisting at 18 in England’s Imperial Police, he was keeping an uneasy post-World War I peace in colonial Burma during the years Steinbeck dropped in and out of Stanford and worked as a day laborer with the Salinas Valley’s multicultural farm workers.

George Orwell and John Steinbeck were born within a year of one another, middle-class children of dominant mothers and distant fathers who displayed an early aptitude to act out for the benefit of family and friends.

By the late 1920s, Steinbeck was a jobless writer living in San Francisco with an unsuccessful first novel. During the same period, Orwell was washing dishes in Paris and harvesting hops in England, collecting material for Down and Out in Paris and London, his first book. Meanwhile Steinbeck married a freethinking leftist who introduced her husband to local labor organizers agitating for better conditions for field workers and Orwell married a brave socialist who joined him on the fighting front in the Spanish Civil War. Orwell’s wife died in 1945 during a botched hysterectomy. George Orwell wasn’t at her side. John Steinbeck and his wife divorced in 1943. She survived the marriage, but probably had a similar procedure at her husband’s insistence before it ended. Orwell remarried in 1949, shortly before his death. Steinbeck in 1950, the year Orwell died.

Why George Orwell and John Steinbeck Failed to Meet

Steinbeck published The Grapes of Wrath shortly before World War II erupted in Europe. It was his eighth book and became a bestseller at home and abroad. George Orwell published Coming Up for Air, his seventh, later the same year. It sold badly, both in England and in America. Ill and unfit for duty when England declared war against Germany in 1939, Orwell joined the Home Guard and worked as a writer, producer, and broadcaster for the BBC in London through 1943. When Hoover’s files on Steinbeck prevented him from getting a commission after America entered World War II, Steinbeck—like Orwell—put his writing in his nation’s service producing literary propaganda until he was cleared by his government to report on the war in 1943.

If the gods meant for George Orwell and John Steinbeck to meet, 1943 was their moment.

If the gods meant for George Orwell and John Steinbeck to meet, 1943 was their moment. Both writers were living in London during the early months of the year, socializing with foreign figures and writing for domestic consumption. But the 41-year-old American and the 40-year-old Englishman moved in alien worlds, distanced not by language or belief but by literary and cultural politics across the deepening Anglo-American divide. Orwell was an internationalist, a journalist who insisted that all prose—including fiction—is political. He disliked Huxley, Auden, and Isherwood, English writers of his generation who moved to America in the decade before World War I, and he considered American writers like Lewis, Anderson, and Steinbeck reactionary because their subjects were regional in focus. Chauvinistic to his core, Orwelll never traveled to America, criticized American consumerism, and publicly disparaged the decadent culture of the country he refused to visit. He also kept literary grudges, and The Grapes of Wrath had been a sensation.

Like ships passing in a storm, Orwell and Steinbeck were in London at a crucial moment without leaving a record of ever meeting. Both men were permanently changed by their World War II experience, and both went on to write books of continuing popularity that reflected the transformation produced by hot and cold world war in their political thinking. But the story behind Orwell’s accusation that Steinbeck was a communist didn’t end with World War II.

Read more in Animal Farm, 1984, and Steinbeck’s Russian Journey.