Despite writing classic books read by millions, John Steinbeck wasn’t on the approved list of great writers when I attended Wake Forest and pursued my PhD at the University of North Carolina. I chose to study the connections between William Blake and William Butler Yeats for my dissertation and taught classic books by other great writers (not Steinbeck) to bored college students before returning to Wake Forest to work as university editor. There I reported to Wake Forest’s legendary provost, a popular English professor who inspired a love of Blake, Yeats, and classic books and plays of the Irish literary renaissance in generations of students like me. We shared an interest in new drawings, particularly creative images of great writers, and he introduced me to the literary portrait etchings of Jack Coughlin, a professor of printmaking at the University of Massachusetts. I love creative images as much as classic books, and Coughlin brought these passions together in new drawings of established writers sold at affordable prices. When the artist issued new drawings of Irish writers in a limited edition, I bought a copy of his haunting portrait of Yeats. For 35 years it has followed me wherever I moved.

Despite writing classic books read by millions, John Steinbeck wasn’t on the approved list of great writers when I attended Wake Forest and pursued my PhD at the University of North Carolina. I chose to study the connections between William Blake and William Butler Yeats for my dissertation and taught classic books by other great writers (not Steinbeck) to bored college students before returning to Wake Forest to work as university editor. There I reported to Wake Forest’s legendary provost, a popular English professor who inspired a love of Blake, Yeats, and classic books and plays of the Irish literary renaissance in generations of students like me. We shared an interest in new drawings, particularly creative images of great writers, and he introduced me to the literary portrait etchings of Jack Coughlin, a professor of printmaking at the University of Massachusetts. I love creative images as much as classic books, and Coughlin brought these passions together in new drawings of established writers sold at affordable prices. When the artist issued new drawings of Irish writers in a limited edition, I bought a copy of his haunting portrait of Yeats. For 35 years it has followed me wherever I moved.

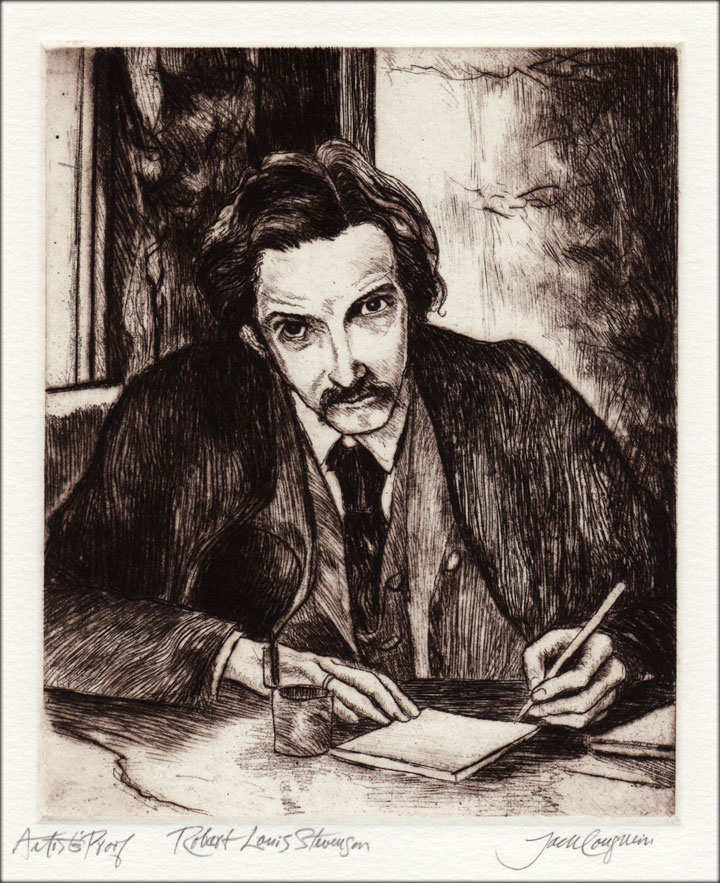

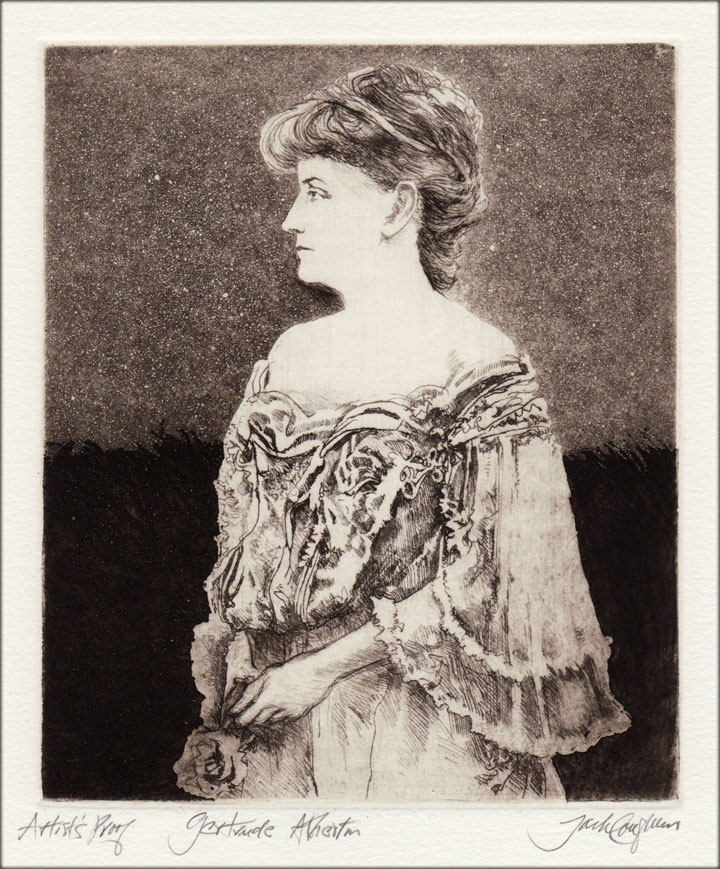

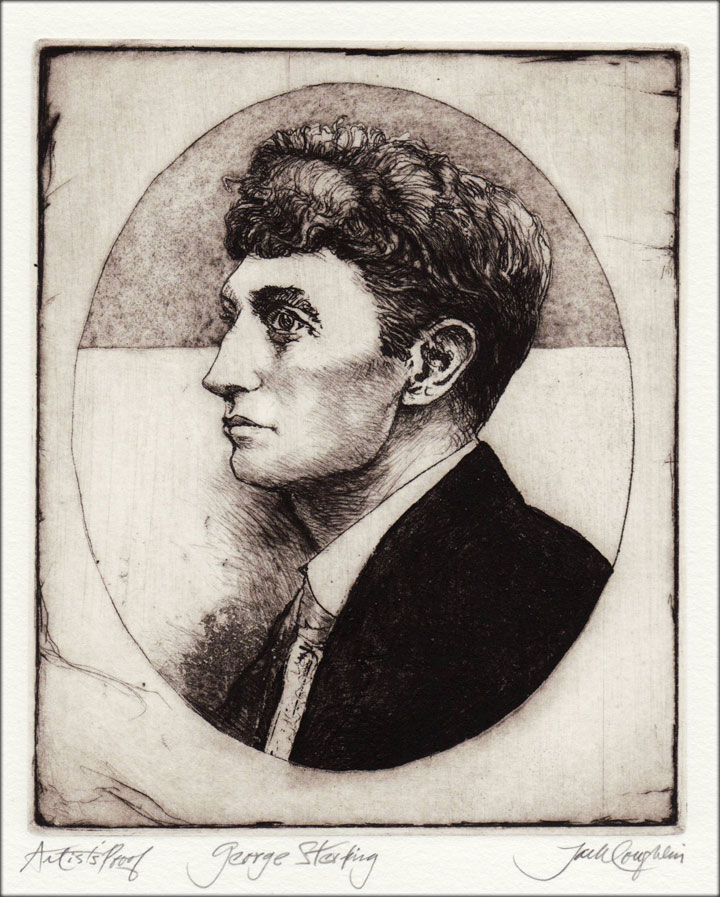

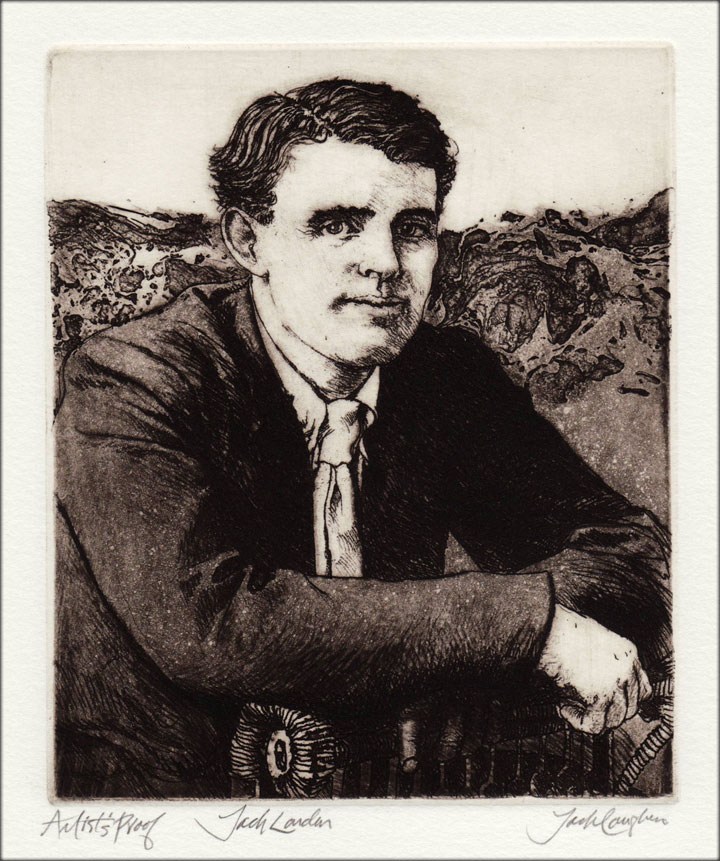

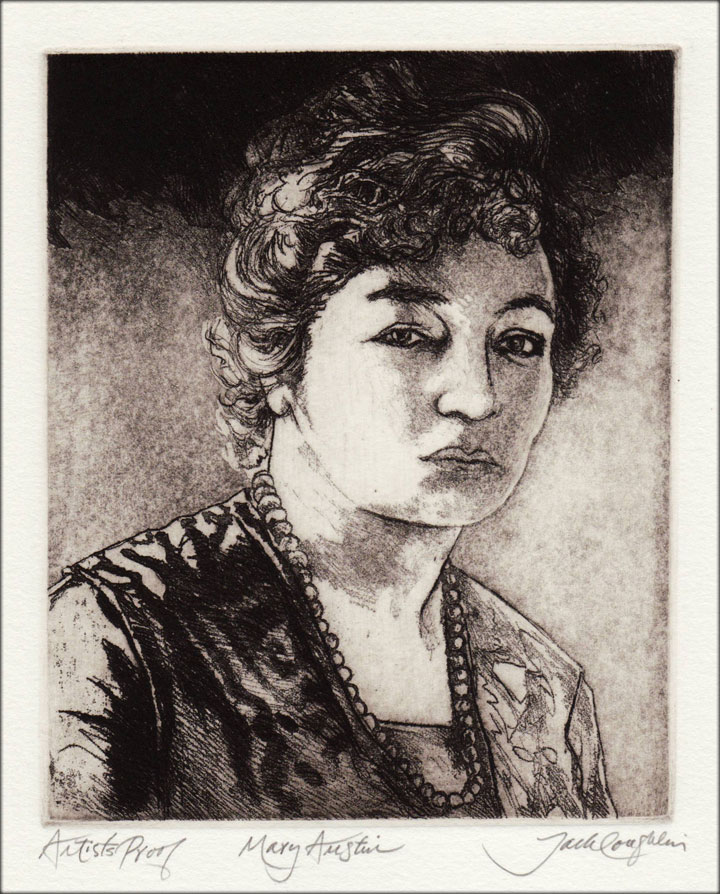

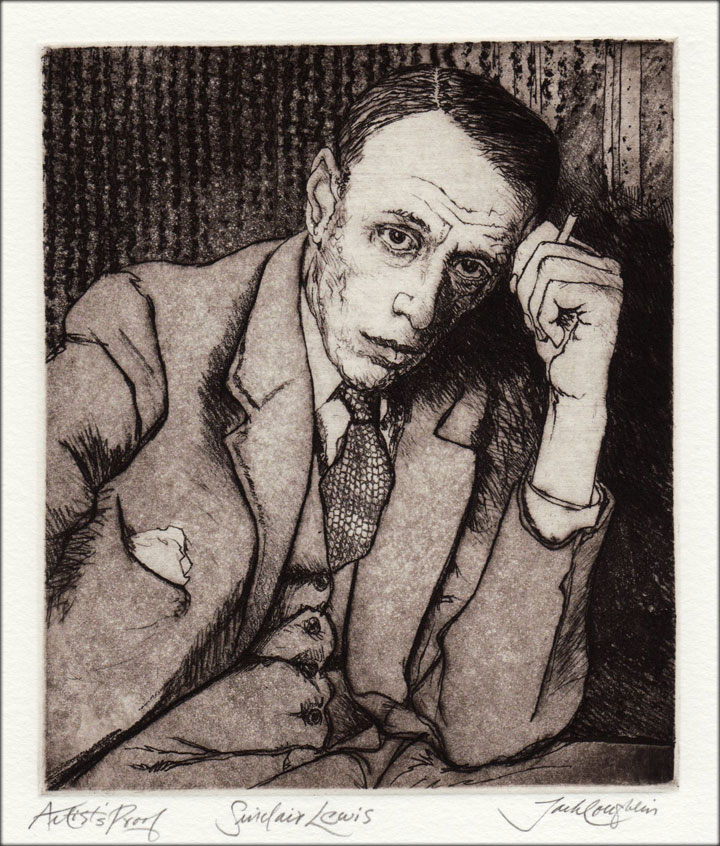

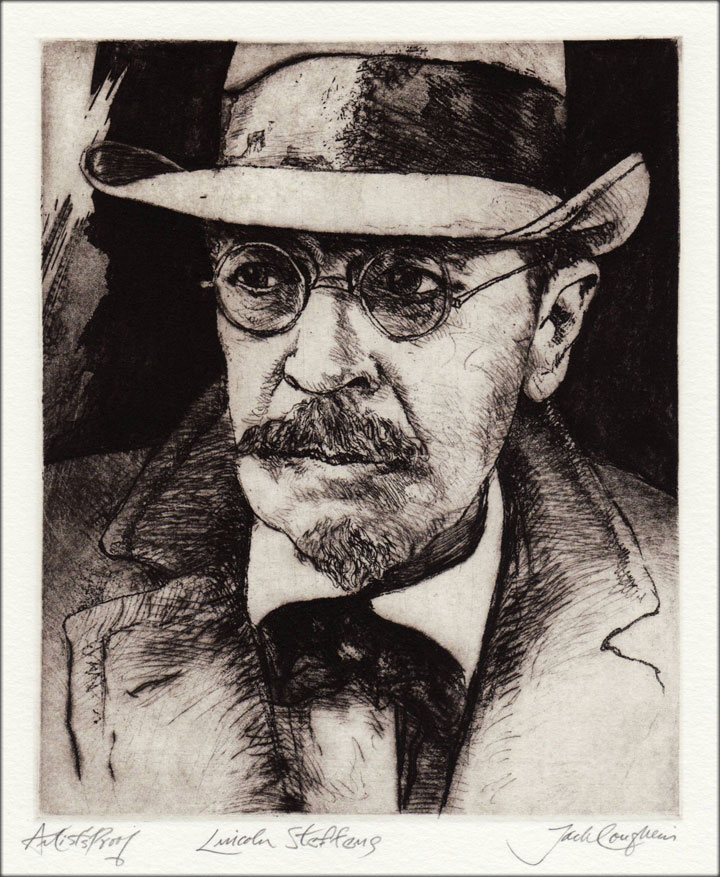

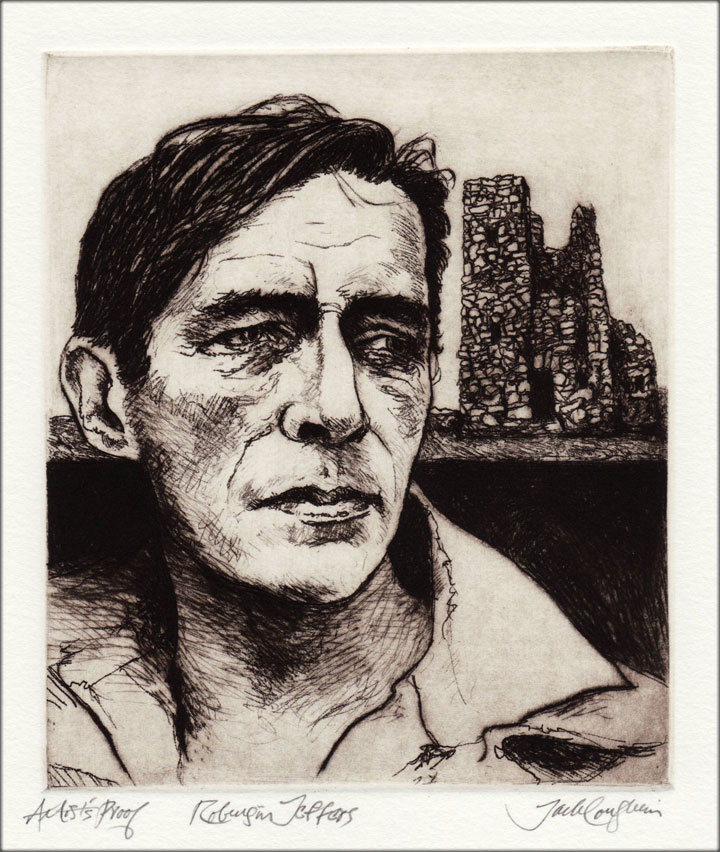

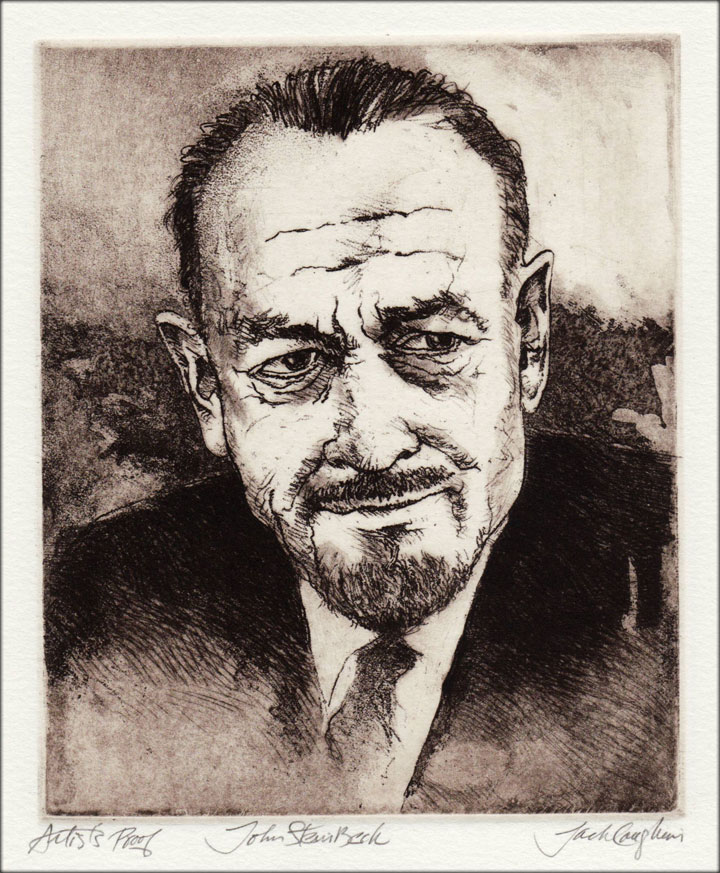

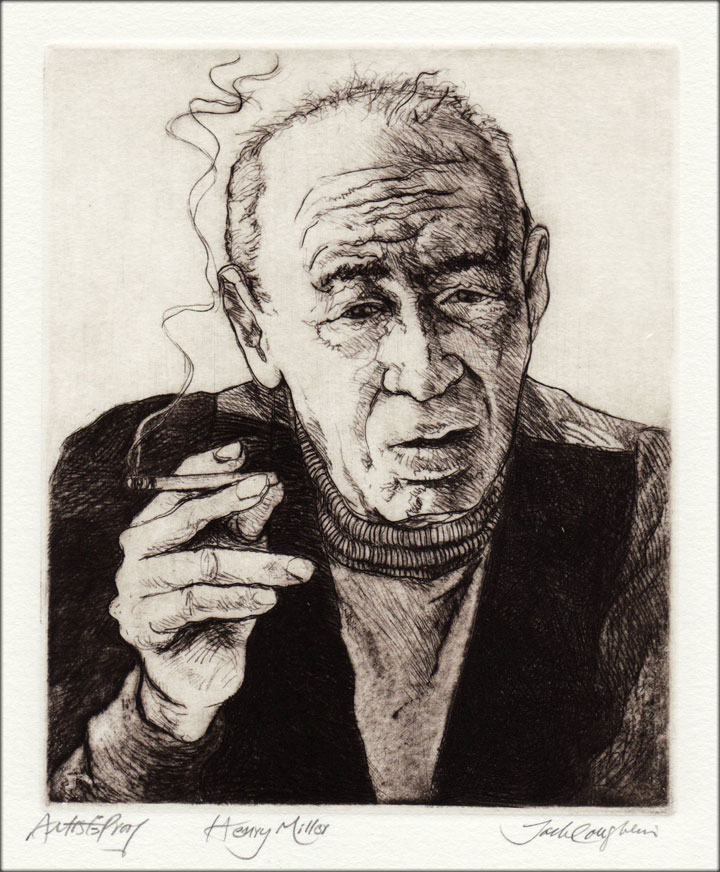

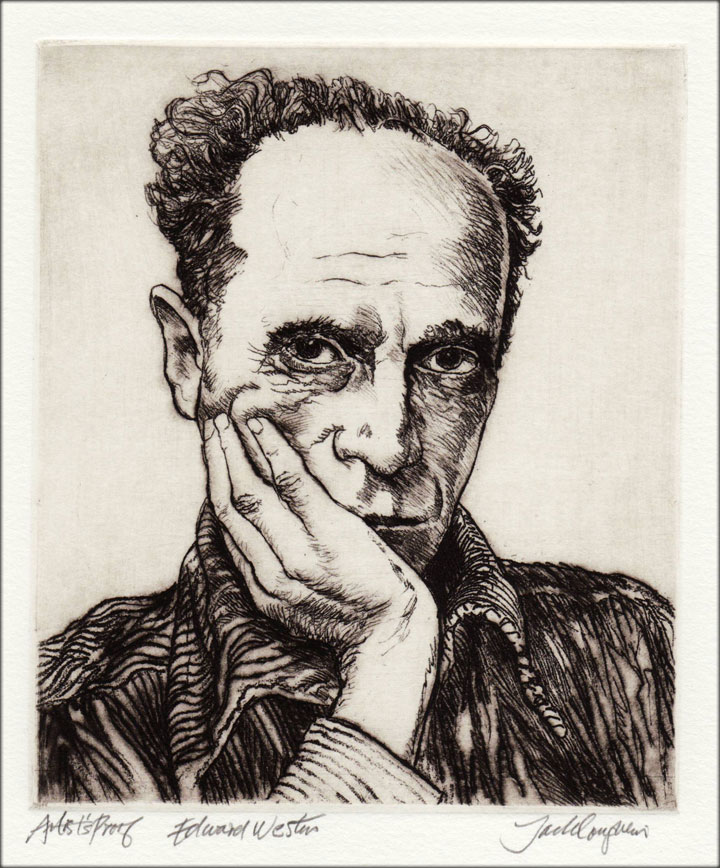

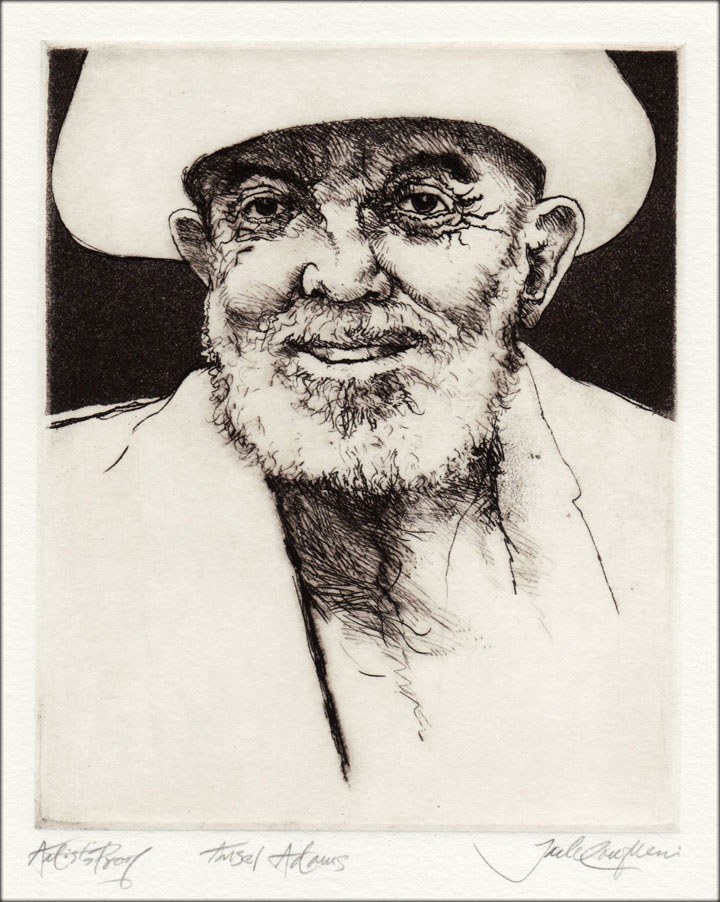

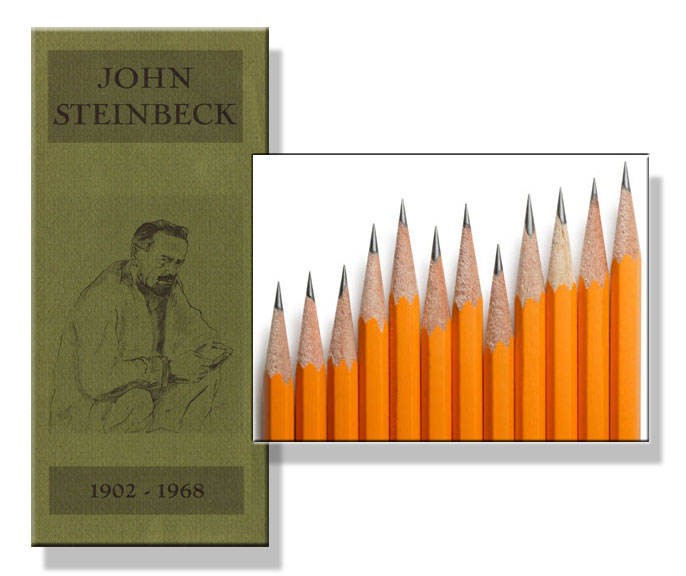

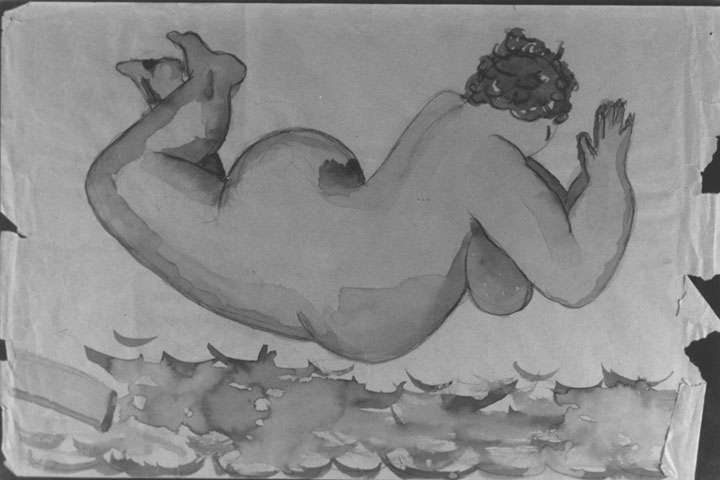

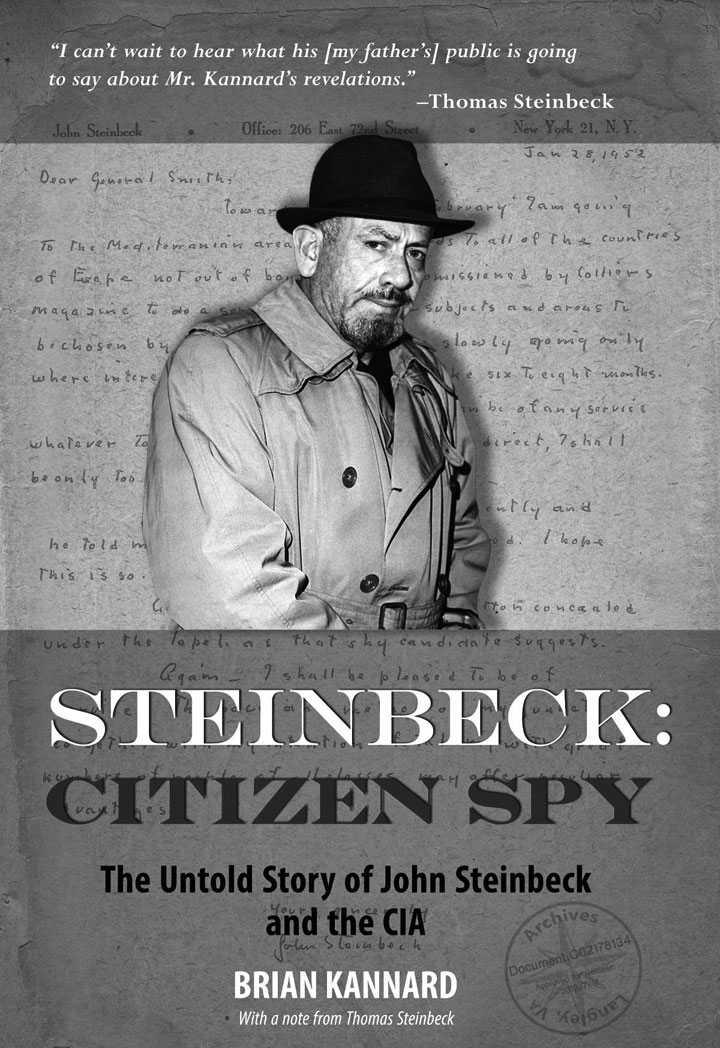

I finally read the classic books of John Steinbeck after relocating to the Bay Area and becoming the weekend organist at St. Paul’s, the great writer’s childhood church in Salinas. So I was searching for old books about Steinbeck, not new drawings, when I rediscovered the creative images of Jack Coughlin at a Monterey bookstore after church one Sunday last month. Delighted, I perused and purchased Impressions of Bohemia, a limited-edition boxed folio of new drawings by Coughlin of a dozen writers and artists—including Steinbeck—associated with Monterey, Carmel, and Big Sur. Published in 1986 by Pacific Rim Galleries, Coughlin’s creative images of California’s Central Coast Bohemians made a superb self-gift, and Steinbeck now hangs next to Yeats in my home, as in my heart. In addition to creative images, the folio features selected passages from classic books, poems, or journals written by Coughlin’s celebrated subjects, plus lively commentary by Richard Dillon, a popular writer of classic books about California history. Dillon’s vivid prose delivers several pleasant surprises. For example, Carmel’s Point Lobos, where family members scattered Steinbeck’s ashes in 1968, was discovered for literary purposes 90 years earlier by Robert Louis Stevenson, the author of Treasure Island and other classic books read by Steinbeck as a boy. It’s also where friends of Jack London—another author admired by Steinbeck—scattered the ashes of London’s lover 60 years before Steinbeck died.

If you’re like me and enjoy owning classic books and new drawings, particularly creative images of great writers in collectible formats, keep your eye open for Impressions of Bohemia, limited to 125 signed copies when published. Meanwhile, Jack Coughlin’s creative images of great writers and jazz musicians—a particular passion of Steinbeck, who collected records and books with equal relish—are available for purchase online at www.jackcoughlin.com/.

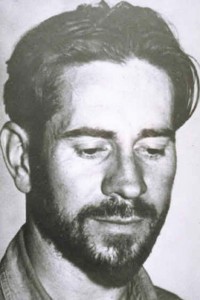

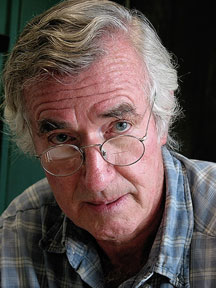

Photo of Jack Coughlin by Ken Buck.