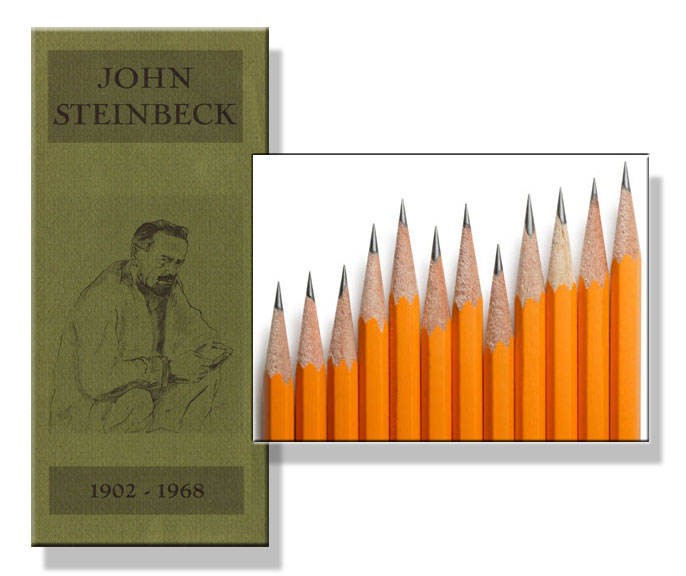

John Steinbeck always had a good word for the pencil.

John Steinbeck always had a good word for the pencil.

Among modern authors, Steinbeck probably best understood the intimate dynamic between the writer and that reliable, albeit low-tech, tool of the trade. The author of The Grapes of Wrath could look at his favored Blackwing itself and see instead a lightning rod.

“It occurs to me,” he wrote a generation ago, “that everyone likes or wants to be an eccentric and this is my eccentricity, my pencil trifling.” At the same time, though, the habitual tinkerer with things mechanical knew his was no mere crotchet, insisting that “just the pure luxury of long beautiful pencils charges me with energy and invention.” For John Steinbeck, there was no better tool for writing. As he explains to editor Pascal Covici in Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters: “I am ready and the words are beginning to well up and come crawling down my pencil and drip on the paper. And I am filled with excitement as though this were a real birth.”

The author of ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ could look at his favored Blackwing itself and see instead a lightning rod.

These letters, written as Steinbeck drafted “the story of my country and the story of me,” contain an embedded paean to the pencil and its singular role in the author’s manner of creation. No better example of this love affair with lead-and-wood is his letter of March 22, 1951. “And now, Pat, I am going into the fourth chapter,” he writes. “You know, I just looked up and saw how different my handwriting is from day to day. I think I am writing much faster today than I did yesterday. This gives a sharpness to the letter. And also I have found a new kind of pencil—the best I have ever had. Of course it costs three times as much too but it is black and soft but doesn’t break off. I think I will always use these. They are called Blackwings and they really glide over the paper. And brother, they have some gliding to do before I am finished. Now to the work.”

‘You know, I just looked up and saw how different my handwriting is from day to day. I think I am writing much faster today than I did yesterday. This gives a sharpness to the letter. And also I have found a new kind of pencil—the best I have ever had.’

Given the worldwide embrace of John Steinbeck’s work over recent decades, it is reasonable to conclude that the Nobel Prize winner has done as much for the pencil’s reputation as Mark Twain did for the cigar’s popularity in an earlier era.

Consider this 2009 entry from the online site Palimpsest: “During his life he wrote 16 novels, eight works of non-fiction, one short-story collection, two film scripts and thousands of letters. He did use the typewriter at some point but his pencils remained his preferred writing instruments. His right ring finger had a great callus—‘sometimes very rough . . . other times . . . shiny as glass’ from using the pencil for hours on end. . . . The use of the electric sharpener was part of the daily routine…as he started the day with 24 sharpened pencils which needed sharpening again and again before the day was through. The electric sharpener must have worked full-time especially during the process of writing East of Eden, for which he used some 300 pencils.”

It is reasonable to conclude that the Nobel Prize winner has done as much for the pencil’s reputation as Mark Twain did for the cigar’s popularity in an earlier era.

Even today the Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University pays unintentional homage to the author’s favorite writing instrument. On its homepage the center proudly notes “its non-circulating archive” of “items . . . unique, rare, or hard to replace.” Accordingly, it advises visiting scholars: “Pencils, not pens, must be used in taking notes.”

Archival best practices aside, is there a contemporary lesson to draw from John Steinbeck’s pencil fetish? Most certainly. Good writing, at its core, arises from the solitary, single-minded dedication to bringing forth the sharp words, the best words, words that etch readers’ consciousness with the force of inevitability. No fallback on the latest apps, no handy distractions from IM—just the age-old wrestling for one’s right words in one’s true voice. The simple pencil, it seems, is the perfect equipment for that kind of contest.

When he was completing his East of Eden draft, Steinbeck observed that writing “is a very silly business at best. There is a certain ridiculousness about putting down a picture of life. And add to the joke—one must withdraw for a time from life in order to set down that picture.”

Good writing, at its core, arises from the solitary, single-minded dedication to bringing forth the sharp words, the best words, words that etch readers’ consciousness with the force of inevitability.

As John Steinbeck might say, it all comes down to the writer and his pencil.

Then again, Steinbeck might well repeat something he also wrote to Covici: “You know I am really stupid. For years I have looked for the perfect pencil. I have found very good ones but never the perfect one. And all the time it was not the pencils but me.”

.

I know what to give all my writer friends for Christmas: a copy of this piece and a set of sharpened Blackwings. Charming. Thanks!

Great idea. Nobody has to remind you to get the lead out by shopping early this year!

Given your great taste in writing tools and your charitable taste in middlin’ commentary, pls feel free to pencil me in as a friend. Joe McK

This is a truly illuminating piece and one that, had I the printer’s ink, I would print out and refer – with all credits – to you, for you write like a man who knows and channels his ideas with wisdom and clarity. This is a rare thing in such an EM Forster-like world of muddle.

I love pencils – always have, always will. As a builder and carpenter the pencil mark reflects a conciseness that enables me to stand and think and look and imagine a construction in wood primarily before setting to the work. The pencil allows me to write slowly, sharpen ideas and focus on what is to come in the process of communicating – mostly to myself (much in drawing pictures too) but significantly to others.

I wonder if I may recommend Knut Hamsen’s ‘Hunger’. A fine book in which the pencil becomes a thing of almost total worship.

Thank you

Thank you for your comment and consider your recommendation accepted!

Excellent piece! I love Paper Mate Twist Tip Advance (Sharp Writer) mechanical pencils, used when I edit my work or take notes from lectures. Steinbeck must have had a well – functioning electric pencil sharpener. I gave up on the electric when my number 2 regular pencils wouldn’t sharpen straight. Happily, the Paper Mates are disposable, so I keep them on hand. When one is used up, I move to the next without missing a beat.

As the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reports today, the maker of Blackwing pencils has a new subscription club for those who cherish the basic tool that separates the great wordsmiths from the crowd. Steinbeck would be especially pleased.

I do not understand the choice of the yellow pencils for the illustration for this article. Common, everyday yellow pencils of unknown pedigree.

I thought it was very well known that Steinbeck used exclusively the Blackwing 602, and followed a structured routine for their care and handling.