Three young artists from Jacmel, Haiti never heard of John Steinbeck before visiting the Bay Area recently to exhibit their art at the Institute of Mosaic Art in downtown Berkeley. Like Steinbeck’s writing, the quality of their painting, papier-mache, and mosaic art—sampled here—speaks for itself. But the story of how three Kreyol-speaking youth found themselves in John Steinbeck’s back yard would have pleased the author, a global thinker and forceful advocate for social justice, individual freedom, and creative art in every imaginable medium.

Three young artists from Jacmel, Haiti never heard of John Steinbeck before visiting the Bay Area recently to exhibit their art at the Institute of Mosaic Art in downtown Berkeley. Like Steinbeck’s writing, the quality of their painting, papier-mache, and mosaic art—sampled here—speaks for itself. But the story of how three Kreyol-speaking youth found themselves in John Steinbeck’s back yard would have pleased the author, a global thinker and forceful advocate for social justice, individual freedom, and creative art in every imaginable medium.

As with John Steinbeck, Art is Our Youth’s Key to Survival

As with John Steinbeck, Art is Our Youth’s Key to Survival

My business is marketing research. My passions are children, art, and travel, which led me to Haiti. Four weeks after returning from my first trip to Jacmel in 2002, I incorporated ACFFC, a grassroots nonprofit inspired by the renowned Haitian-American artist Turgo Bastien. Nurturing children’s art talents at an early age provides a path for survival, self-expression, and self-sufficiency, particularly in Haiti. When I started Art Creation Foundation for Children (ACFFC) more than 10 years ago to provide a place for Jacmel, Haiti’s poorest children, introducing them to John Steinbeck was probably the last thing on my mind. My mission at the time was first-things-first: clothing, feeding, and schooling a handful of kids with no resources, no future, and frequently no food, wandering the ancient streets of Jacmel.

Jacmel was the architectural model for New Orleans (where John Steinbeck wed his second wife and where my son was married for the first and only, thank God, time). Although located only 1,300 miles from New Orleans in the poorest nation of the Western Hemisphere, Jacmel was once a prosperous port. But like John Steinbeck’s Salinas, its most talented children tend to migrate elsewhere. Children’s art training and community art projects are contributing to the recent revival of the city’s economy, reputation, and quality of life. This is the entrepreneurial part of our educational purpose.

Artists from Jacmel, Haiti Discover Steinbeck Country

Artists from Jacmel, Haiti Discover Steinbeck Country

Remember the Beatles’ line: “I get by with a little help from my friends”? That’s how Art Creation Foundation for Children grew.

From an initial group of four boys and four girls (we started and stayed with a 50/50 boy-girl rule), ACFFC has become an established organization that clothes, feeds, and schools more than 100 young people ages 3-22, also teaching older children how to make art and build homes using recycled materials such as styrofoam, bottles, and broken glass. Artists and businesses volunteer their time, money, and services, so ACFFC has remained extremely cost-effective. In Jacmel we employ an executive director, an assistant, kitchen and maintenance staff, an English teacher and three tutors, plus one full-time artist. Visiting artists and other professionals travel to Haiti from the U.S. to teach and lead children’s art programs for weeks at a time.

Laurel True, a celebrated mosaic artist and teacher who founded the Institute of Mosaic Art in Oakland and now lives in New Orleans, first brought the mosaic arts to our curriculum in Jacmel following the 2010 earthquake. She conceived and now directs our respected Mosaique Jacmel initiative, the reason 10 of our youth were invited to travel to the U.S. in November for a collaborative project with the Touissant L’Ouverture High School for Arts and Social Justice in Delray Beach, Florida. The American Embassy’s Office of Public Diplomacy in Port-au-Prince, Haiti was a project sponsor. U.S. Representative Lois Frankel, also an artist and advocate for children’s art, helped with arrangements and met with the group.

Mosaic Art Celebration: John Steinbeck’s Kind of Party

Mosaic Art Celebration: John Steinbeck’s Kind of Party

Three ACFFC youth also made their way to the Bay Area as part of the tour: mosaic artists and team leaders Michou Joissaint and Jepte Milfort, along with photographer Fedno Lubin. More than 100 Bay Area mosaic artists, collectors, and supporters attended the reception in their honor at the Institute of Mosaic Arts hosted by Ilse Cordoni, IMA’s new owner, and Erin Rogers, the Hewlett-Packard Corporation’s Environment Program Officer and an ACFFC board member who traveled to Jacmel, Haiti, with Laurel True following the earthquake.

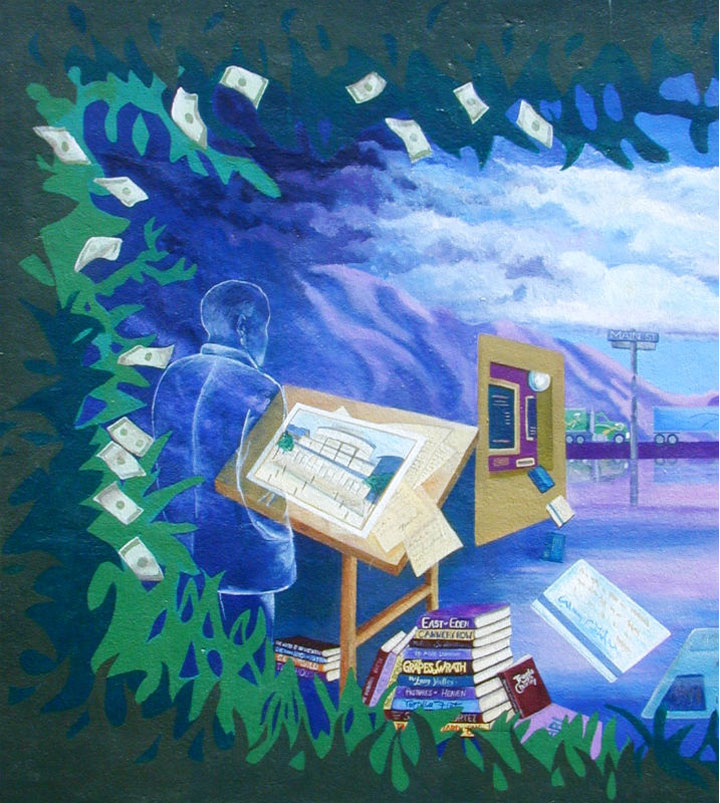

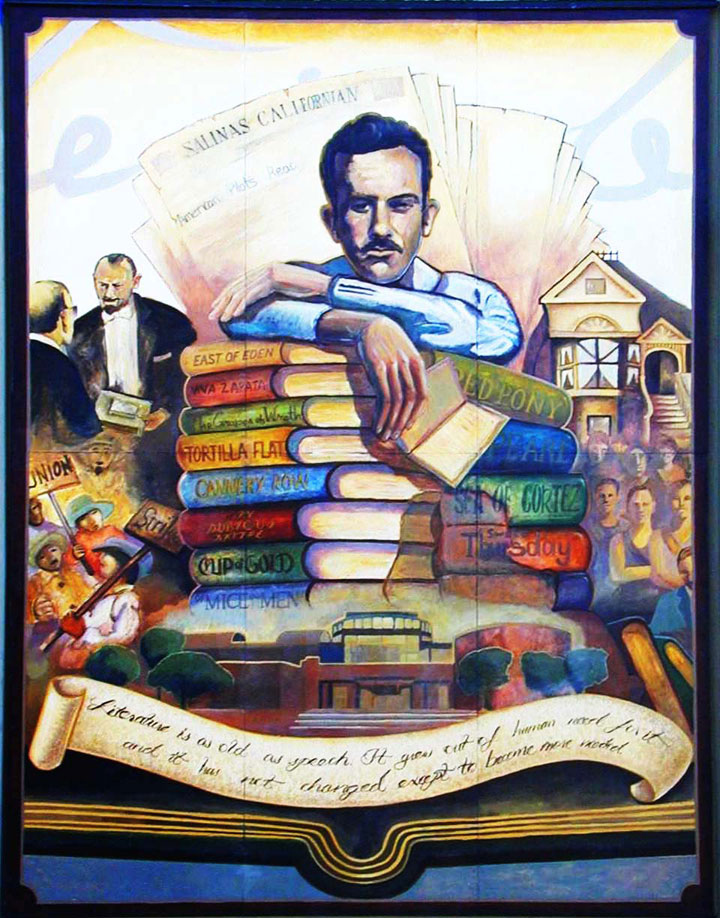

Some speculate that John Steinbeck was a citizen spy for the CIA. Whether that’s true or not, I think he would have liked the story of how three young artists from Haiti discovered Steinbeck Country on their cultural mission to California. He had an educated eye for art and loved to draw and make things, so I know that he would find these examples of ACFFC mosaic art, papier-mache, and painting equally appealing. I hope you do as well. If you would like to learn more, make suggestions, or support ACFFC’s work in Jacmel, we would love to hear from you.