For this my Miata was made. A man, a towel, a mug, and rag top down. She may have struggled driving over the silt and rocks of the Monument Valley trail. She may have sneezed from the exhaust fumes of flatbeds and semi-trucks. But now my little car was in road rally heaven. This is what she was made for. Her adrenalin was up. Tight on the turns. Anyone can speed up on the straightaway. I love accelerating on curves. It is the story of my life. By the way, in case you haven’t heard, Convertible Top Down is mandatory on the California coast. Citizens approved this rule in one of their incessant ballot-box initiatives. Proposition 42, I do believe—but who else other than Californians is counting?

For this my Miata was made. A man, a towel, a mug, and rag top down. She may have struggled driving over the silt and rocks of the Monument Valley trail. She may have sneezed from the exhaust fumes of flatbeds and semi-trucks. But now my little car was in road rally heaven. This is what she was made for. Her adrenalin was up. Tight on the turns. Anyone can speed up on the straightaway. I love accelerating on curves. It is the story of my life. By the way, in case you haven’t heard, Convertible Top Down is mandatory on the California coast. Citizens approved this rule in one of their incessant ballot-box initiatives. Proposition 42, I do believe—but who else other than Californians is counting?

It had taken hours to drive up Route 1 from the Ventura Highway to Steinbeck Country north of Santa Barbara, wending, weaving, winding along the switch-back curves along the Pacific Coast, some with guard rails, some without. Then Moro Bay. Seal Point with hundreds of seals lolling about on their backs and bellies, tossing sand over themselves with their fat flippers. A few miles beyond, the overweight ostentation of Hearst Castle, built high above the surrounding countryside, trying mightily to look impressive. No, the seals are impressive. The expanse of the Pacific is impressive. Your castle is gaudy.

Americans don’t need guillotines; we have the American Dream.

Hey, buddy, somebody should tell you: This is America. We don’t have castles. We don’t buy into barons, lords, and sultans. Wealthy citizens might try to re-create Europe’s feudal system, but we peasants have a way of rising up and kicking out aristocrats. Americans don’t need guillotines; we have the American Dream.

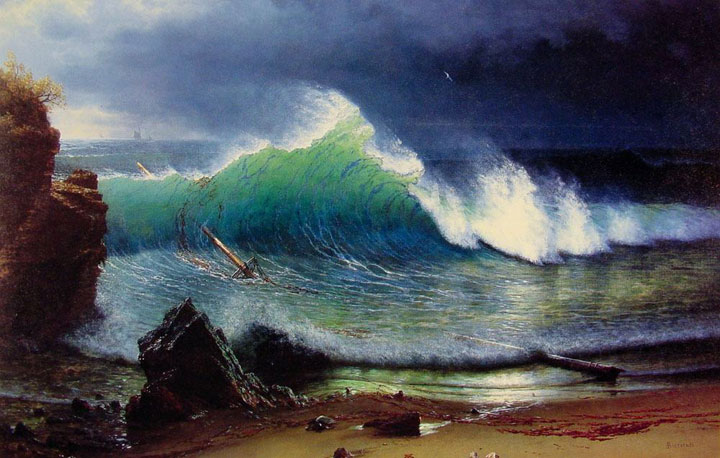

The jagged coastline of California is always the winner in a beauty contest between nature and humankind. Green grass and lush vegetation crouch up against cliffs and rocks below. Curling waves of cobalt blue crash in bright, white spray. Streaks of aquamarine signal changing currents and temperatures. Big Creek Bridge. The 1932 Bixby Bridge. Then Big Sur with its towering trees and hairpin turns. An elven glen—a place of sprites, hikers, and Zen spiritual seekers. John Steinbeck once wrote this to Adlai Stevenson: “Having too many things they spend their hours and money on the couch searching for a soul.”

‘Having too many things they spend their hours and money on the couch searching for a soul.’

North of Carmel, at Monterey, a right turn to Salinas, my final destination.

From Colorado Shepherd to Salinas Priest

From Colorado Shepherd to Salinas Priest

Father James Ezell, the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, drove up to greet me as I loitered in front of the National Steinbeck Center. Steinbeck once suggested a bowling alley if the people of his home town insisted on putting his name on a building. I followed Jim in my car to the current rectory of St. Paul’s, where I would spend the night.

As a boy John Steinbeck served as an acolyte at St. Paul’s when the church was located downtown, on a corner now occupied by an empty parking lot. The St. Paul’s rectory described in East of Eden still exists; today it serves as a law office. They say that Cesar Chavez, champion of the United Farm Workers, held meetings at St. Paul’s with the support of the church’s rector in 1970. Wealthy growers left the church as a result. Some churches want their ministers to be mascots. Or marionettes. But it doesn’t, or shouldn’t, work that way. The moment a pastor worries about losing his or her position is the time that pastor deserves to lose his or her position.

Some churches want their ministers to be mascots. Or marionettes. But it doesn’t, or shouldn’t, work that way.

Oh, I can’t really call the current rector of St. Paul’s “Father Ezell.” He’s Spiff. He’s Jim. He’s been my friend since junior high school. We first met near Detroit on my family’s cross country drive in our old Dodge Motor Home. Our mothers had been cheerleaders together at Westfield High, and my brother remembers seeing a photograph of the prettiest girl he ever saw—Jim’s sister Kathy—at their house. He wanted to meet her, but she was away at tennis camp. He ended up marrying her anyway. Jim, who was a hood with rolled up T-shirt sleeves and a cigarette pack in high school, once worked as a shepherd in Colorado before finishing Alfred College, where he met his wife Lynn.

Later the priesthood beckoned. His first parish was in Asheville, North Carolina, followed by decades working as a chaplain, teacher of Christian education and social studies, and boarding home master to 64 boys in Brisbane, Australia, who come in from the bush for their schooling. The children of parents with ranches requiring two days to cross by motorcycle, their only educational alternative was short-wave radio. A far cry from Steinbeck’s ranchers, a close, clubby group.

Life East of Eden in Steinbeck’s Paradise

Life East of Eden in Steinbeck’s Paradise

Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley is located between the Santa Lucia Mountains and the Gabilan Range, named for the hawks that soar among the hills, predators on the prowl around Fremont Peak. With some justice it’s called the Salad Bowl of the world. Its rich alluvial soil produces most of the lettuce used in the salads we eat. Plus strawberries, potatoes, grapes, and more.

The town of Salinas was already an agricultural center when John Steinbeck was grew up there. Today visitors can take an East of Eden walking tour, following Kate’s path to the bank to the corner of Castroville (now Market) and Main streets where she deposits the earnings from the bordello she owns. Steinbeck wasn’t always welcomed home after he left Salinas, where copies of The Grapes of Wrath—the book that exposed the plight of migrant workers a generation before Cesar Chavez—were burned in the street. Steinbeck’s was the disturbed and disturbing sadness of someone who knew how to see. Learn to look, he urged readers. Just observe. Shove aside presumptions and preconceptions. Steinbeck called it “non-teleological thinking,” and not everyone in Salinas understood.

Steinbeck called it ‘non-teleological thinking,’ and not everyone in Salinas understood.

Twelve miles south of Salinas, down the valley, is Soledad, a name that translates as both solitude and loneliness. It is the setting of Steinbeck’s novella Of Mice and Men. George and Lennie are ranch hands wandering from work to work, hanging on to the shards of their dream about a little piece of land of their own and rabbits for Lennie. Brawn coupled with ignorance spells sorrow. Lennie kills Curly’s wife because her panic frightens him. George does what he must to protect the friend he promised he would look after from being lynched by Curley’s gang. Trapped men. Imprisoned men. Lonely men.

Spiff reminds me that Soledad today is famous as the home of Soledad prison. The prison on one side, agriculture on the other. Families following their jailbird sons, husbands, and boyfriends have led to a recent increase in gang violence throughout the valley. The day after I left Salinas for San Francisco, police and federal agents in an action called Operation Knockout arrested 37 members of the Norteno drug gang in a neighborhood near the rectory of suburban St. Paul’s.

While waiting for Jim to meet me outside the National Steinbeck Center on my first day in Salinas, I watched an elderly man poke his walking stick into a trash bin. He wore a turquoise cap, a blue and white windbreaker, and grey slacks. Rummaging through the garbage, he pulled out a plastic bottle, dumped the remnants of the soda, squashed it with his sneaker, and stuck it into his plastic bag. He moved on, harvesting from other bins located along Main Street. If you don’t have a job and gather enough bottles and plastic, you can make a few bucks from recycling.

If you don’t have a job and gather enough bottles and plastic, you can make a few bucks from recycling.

Following dinner with Jim, Lynn, and their daughter at Clint Eastwood’s Restaurant in Carmel-by-the Sea—and a decent night’s sleep—I awoke to my first rain in 3,000 miles on the road. Before Jim dropped me off at the Center and drove back to his offices to prepare for a funeral, he took me to meet his friend the Methodist pastor. In partnership with local Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches, the Methodists and Episcopalians of Salinas operate a drop-in center for hundreds of homeless men, women, and children. That day these folk waited inside, out of the rain, for the free lunch the churches provide daily. They were going to have enchilada casserole.

The homeless of Salinas could also change their wet clothes for dry garments from the clothing ministry. The Methodist church library, which once featured religious books read by few, now serves as a food pantry where canned goods line the bookshelves. Tillich and Barth made way for Heinz and Old El Paso sauce. Counseling services are also provided, along with volunteers who simply listen to these homeless souls tell their stories. A listening ministry. Homelessness, too, means isolation, loneliness, no one to talk with. A van pulled into the cramped church parking area. Clinica de Salud. This was dentist week. Salinas churches also participate in the I-Help ministry, rounding up the homeless in vans and bringing them to area churches for a safe, warm night off the streets.

The Truth of Grapes of Wrath Marches On

The Truth of Grapes of Wrath Marches On

This is the California where the story told in The Grapes of Wrath ends. Between 300,000 and 500,000 Dust Bowl migrants, Steinbeck’s “Harvest Gypsies,” left ruined farms in towns like Sallisaw, Oklahoma, drove the Route 66 exodus trail, and huddled together in caravans of the desperate and disillusioned, hoping to reap the abundance of California as laborers for hire. Back home they suffered from bad agricultural practices, sustained drought, and financial indebtedness. They arrived in California to experience hostile police, apocalyptic floods, and even deeper debt.

One diary of a worker on display at the National Steinbeck Center reads: April 21. Work began today. The price was raised to .30 per hamper. Made 14 hampers which made us $4.20. April 22. Something different. Rain. Rained all day. Couldn’t do anything but stay in tent and read.

I double-checked my pocket calendar. Today was April 20. Seventy-five years ago this destitute diarist was filling hampers for .30 cents. Tomorrow I’ll be taking my daughter and her boyfriend out to an expensive dinner in downtown San Francisco. I’ll use my credit card.

April 20. Later I heard the news on the radio about the explosion on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig off the coast of Louisiana. Eco-disaster. Another Steinbeck theme.

Sallisaw comes from the French word for salt, named for the salt deposits along the streams used by settlers and buffalo hunters to preserve their meat. Salinas also means salt. Salt preserves. Salt brings out flavor. Salt can also heal. Salt is the reason our tears sting.

While I was touring the National Steinbeck Center on my second visit—excited by the touch of a kindred spirit when I recognized Rocinante, the vehicle Steinbeck used to drive America in Travels with Charley—I glanced out the glass entranceway and saw through the drizzle the same fellow in the same clothes harvesting from the same trash bins I’d seen when I arrived in Salinas. Steinbeck would have found it ironic that while I was touring a wing of the museum named for him, local Rotarians arrived for lunch and a program provided by the facility.

Perhaps the Rotarians with their 4-Way Test took time to view the exhibit of photographs in the center’s side hall. I did. It consisted of pictures from around the world—from Vietnam, Haiti, Iraq, Columbia, and beyond—showing victims of war. The display included stories and quotations from the subjects of the photographs. One image depicted an elderly woman, her skin stretched, punctured, and distorted from war wounds. Her body bore the divots of callused causes. Her caption read: My body took the brunt of the bullets but my family was hit hardest. . . . my grandchildren go to bed hungry and crying.

I felt like crying.

The Way Is Open, the Choice Is Ours

The Way Is Open, the Choice Is Ours

Timshel. Steinbeck’s version of a Hebrew word meaning Thou mayest. The way is open. The choice is ours. The word Steinbeck thought was the most important word in the world.

The Grapes of Wrath begins with a drought and ends in a flood. Steinbeck based his fictional flood on a real event that occurred in Visalia, California, 100 miles north of Bakersfield in California’s Central Valley. In the novel what is left of the Joad family huddles together in a rain-soaked barn. They have lost everything except each other. Their grandchild has died and their children go to bed hungry. The Joads’ plight continues today in the sufferings of the grandmother in the photograph, the homeless in the church vans, and the old man in the cap and windbreaker on Main Street, Salinas. Timshel.

The paintings of Albert Bierstadt, shown here, provide visual counterpoint that John Steinbeck would have appreciated. Like Steinbeck, the great Hudson River-Rocky Mountasin School painter was a prolific artist of German heritage who found inspiration in the sublimity of California’s coast and mountains. He died on on February 18, 1902. Steinbeck was born nine days later.