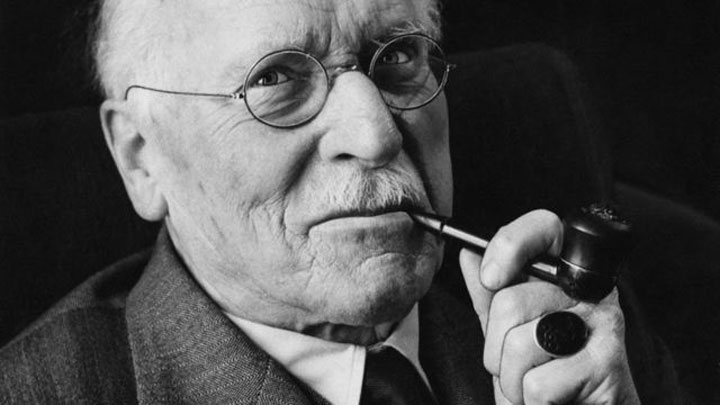

John Steinbeck was ambivalent about psychology. In 1962 he lashed out at his country’s modern “psychiatric priesthood” in Travels with Charley. But 30 years earlier he had stayed up nights discussing the psychological insights of Carl Jung, the great Swiss psychologist-psychiatrist shown here, with Ed Ricketts, Joseph Campbell, and other members of the bohemian Cannery Row circle in the Monterey of his youth. As a result, Jungian principles of a collective human unconscious, the meaning of symbols and myths, and the essential role of certain types of individuals in group behavior inform Steinbeck’s most successful fiction of the 1930s. To a God Unknown and In Dubious Battle are frequently cited examples. As I will show, the insights of Jung in advancing Steinbeck and Ricketts’ phalanx theory are equally evident in Tortilla Flat, the book that launched Steinbeck’s reputation as a promising new writer.

John Steinbeck was ambivalent about psychology. In 1962 he lashed out at his country’s modern “psychiatric priesthood” in Travels with Charley. But 30 years earlier he had stayed up nights discussing the psychological insights of Carl Jung, the great Swiss psychologist-psychiatrist shown here, with Ed Ricketts, Joseph Campbell, and other members of the bohemian Cannery Row circle in the Monterey of his youth. As a result, Jungian principles of a collective human unconscious, the meaning of symbols and myths, and the essential role of certain types of individuals in group behavior inform Steinbeck’s most successful fiction of the 1930s. To a God Unknown and In Dubious Battle are frequently cited examples. As I will show, the insights of Jung in advancing Steinbeck and Ricketts’ phalanx theory are equally evident in Tortilla Flat, the book that launched Steinbeck’s reputation as a promising new writer.

Carl Jung, John Steinbeck, and the Problem of Language

I reached this conclusion not through studying literary theory in a classroom but by reading Carl Jung and John Steinbeck and applying their insights in my three-decade career designing, developing, and leading critical skills and management training programs for corporations such as RCA, KPMG Peat Marwick, Honeywell, AT&T, Blue Cross/Blue Shield of New Jersey, and others. In business, critical skills include tasks where failure to properly perform may cause death, serious injury, or financial loss. Central to the development of cost-effective critical skills training programs in my work was assuring clearly and uniformly understood terms, concepts, and models. To do this, a good instructional designer must define terms and concepts so that training objectives and process are easily communicated and comprehended.

This is usually not too much of a problem in industries and professions that have well-defined lexicons, such as law, engineering, and accounting. It is more difficult when training enters more the ambiguous arena of consulting, marketing, management, and sales. But these activities also require clearly-understood language for personal, interpersonal, team, and group-related tasks. Naturally the field of psychology seems an appropriate place to handle individual, interpersonal, and teaming challenges that arise in the process of doing business and improving outcomes. Yet key terms and basic concepts vary greatly throughout psychology from one school of thought and practice to another. For instance, the essential term ego is defined quite differently by followers of Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud and was ignored completely by later behaviorists such as B.F. Skinner.

Because reliable sources to develop a useful lexicon for applying psychological theories outside the box of clinical psychotherapy are few—and because individual psychologists frequently employ esoteric language and the terms, concepts, and models commonly used are often misunderstood between different schools of psychology—the study and practice of psychology in its various fields and forms is almost universally looked down upon by more precise sciences as fundamentally unscientific. The language problem inherent in psychology is a major reason why empirically-minded biologists and chemists—the sciences that attracted and engaged John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts—continue to hold psychology in low esteem.

Discovering the John Steinbeck-Carl Jung Connection

I have been a Steinbeck fan since I first read his fiction, which I found irresistibly unpretentious, down-to-earth, and clear in style and story. Who could argue with the humor and accessibility of Tortilla Flat, his earliest best seller, for example? As in Steinbeck’s later novels, the characters in Tortilla Flat are so thoroughly defined that you felt you had known them all your life.

After rereading Tortilla Flat approximately 30 years ago, I began to sense a Jungian influence in its narrative flow and structure, an observation that was confirmed when I read the biographies of John Steinbeck that started to appear in the 1980s. When I learned that the young mythologist Joseph Campbell was part of the Cannery Row scene swirling around Steinbeck’s friend Ed Ricketts In 1932, and that Campbell’s correspondence with Ricketts continued until Ricketts’ death in 1948, there was no doubt in my mind about the influence of Carl Jung on Steinbeck’s writing—including Tortilla Flat—during the years that followed. I was equally intrigued to discover that the influence of Carl Jung on John Steinbeck did not originate with Ricketts or Campbell as some have supposed. John Steinbeck was a deep reader with wide interests who took philosophy as a student at Stanford. As a result, he came to Cannery Row in the early 1930s with knowledge about modern psychology.

The Phalanx and “Breaking Through”

The unconscious influence on behavior of individuals—Steinbeck’s “human units”—within an objective focused gathering, group, or MOB that Steinbeck called the phalanx is, I believe, worthy of closer examination today. As mentioned, To a God Unknown and In Dubious Battle are frequently adduced as examples from the fiction of the 1930s. But a piece of nonfiction published by Steinbeck in 1942, Bombs Away: The Story of a Bomber Team, includes a description of the phalanx in the training and development of bomber crews by the wartime Army Air Corps, and The Log from Sea of Cortez explains the phalanx more fully than any other work of nonfiction published in Steinbeck’s lifetime.

The MOB’s objective may seem simply unreasonable or illusionary, such as group bullying or scapegoating those who disagree with the MOB’s belief or creed. But however irrational or inexplicable, it can produce horrors like the Holocaust. Given the explosion of MOB violence around the world in our time and the reported incidence of bullying in our schools, better understanding the phalanx as Steinbeck developed and used the term seems to me to be more important than ever before.

Steinbeck’s phalanx is based in part on Carl Jung’s collective unconscious, as well as on the ideas of philosophers familiar to Steinbeck from his studies at Stanford, such as those of William James—an important influence on Jung himself in my opinion. As a result of Steinbeck’s reading, discussion, and understanding of Jung, James, and others, I believe that he consciously coined the term phalanx, clearly defined it in his thinking, and applied it in his work, including Tortilla Flat.

As also mentioned, the concept is not something Steinbeck acquired from Ricketts but came to him as a result of his personal awakening to a thread connecting random notes that he kept in a cigar box beginning as early as the 1920s. When I read about the writer’s habit of jotting ideas on bits of paper in a leading John Steinbeck biography, I thought to myself, “what a great example of Jung’s Intuition!” Significantly, the connection occurred to Steinbeck during his mother’s long illness and the crisis of caring for the parent who dominated his family and his boyhood.

To use Ed Ricketts’ term, this was a “breaking through” for John Steinbeck at age 33—a life-changing epiphany or event resulting in a leap of personal growth. Practitioners of Carl Jung’s method of psychology recognize how a personal tragedy like the death of a parent can awaken the mind’s eye to a new perspective, a deeper consciousness, and greater understanding. Importantly for my point, such an awakening proportionally reduces an individual’s susceptibility to the negative influence of the phalanx, sometimes by raising his or her resistance to participation in MOB violence and destruction. A desire to break through to deeper knowledge is a defining trait of each of the fictional characters created by Steinbeck, beginning with In Dubious Battle, based on Ed Ricketts.

Levels of Adult Maturity and the Influence of the Phalanx

In developing his phalanx concept, Steinbeck articulated two key characteristics:

* A group, gathering or MOB can take on an autonomous psychology and behave in a manner that may be quite different from what would be displayed by individual members under the same circumstances.

* The psychology of the group frequently appears to be in antagonistic counterpoint to the individual psychology of its human units.

I would add a third point: The higher the development or maturity of the group’s individual members, the less the negative influence exerted by the MOB on the group’s behavior. T

The levels of this development or maturity are fourfold:

Level 1. Level 1 persons are almost completely unaware of their uniqueness as individuals. They have no ego as the term is used in the clinical sense—that is, the psychological object within which an individual defines himself or herself. Those who exist at this level lead lives that revolve around basic survival, shelter, safety, and procreation. They leave decisions on important matters up to authority figures such as a father or mother. During Jung’s research among African and North American Native tribes, tribal members told him that they leave all thinking and decision-making to their tribal chief or medicine person. They could not distinguish between their dream state and conscious state. They told Jung that they thought anyone charged with the burden of thinking was crazy. They were mainly unconscious.

Level 2. Level 2 individuals awaken to the differences between themselves and others. This is the beginning of the existence of their ego: their awakening to their uniqueness in the world or the universe. An individual at this level typically projects onto external gods and devils. As a result of their development they gradually learn to participate in their personal path, create goals, and use individual tools in dealing with life and its issues. But for the most part they are driven to self-serving aims with their newly discovered skills. They still are mainly unconscious.

Level 3. To understand my description of Level 3, we must agree on the definition of the term ego I intend: one’s conscious image of himself or herself. When we reflect upon ourselves, the image we perceive is the ego. The term is often mistakenly used to refer to an inflated ego where the self-image of an individual exceeds reality. But in truth, the ego is the focal point to which all objects of perception must relate to become conscious. Persons at Level 3 have a nearly completely developed ego and view it as their center, denying the existence of anything about themselves outside its circumference. While the Level 3 individual denies the unconscious, they are nonetheless the victim of unconscious influences in their behavior. Examples include embarrassing slips-of-the tongue or falling in love with a person who is wrong for many reasons. They may also be victims of irrational fears or hates—the Shadow, to use another term from Carl Jung, Level 3 persons are apt to become victims of group influence at the MOB phalanx, however emphatically they may deny this possibility.

Level 4. For a variety reasons, some painful, Level 4 individuals have awakened to the reality that there is more to themselves than their ego. Accompanying this realization is a curiosity about their newly revealed psychological territory. It usually doesn’t take them long to explore this uncharted terrain within themselves. Ideally, when they do so they will seek to integrate what they discover about themselves into their existing self-image and further build their ego on stronger ground. The previously unintegrated elements of Self found in their exploration likely were the source of many of the projections they suffered at earlier stages of their development on the way to Level 4 self-knowledge. Level 4 people are thus the most conscious and least vulnerable to phalanx influence. They are truly their own man or woman.

Readers may recognize the differences in persona presented by individuals at the levels I have described. These differences can be perceived through interpersonal dialogue and interaction or through observing behavior. Strong caution must be suggested to avoid pigeon holing another and then acting on that classification. Remember, we are also responsible for the persona we perceive of others and it may be very wrong. Individuals at Level 4 (Ed Ricketts, for example) often appear peaceful, content, friendly, and kind. Those at lower levels may be more easily influenced by fear, hatred, and ignorance. The fiction of John Steinbeck, who I believe intuited this truth about humans, offers unforgettable examples of people at every level of evolution.

The Phalanx in Tortilla Flat

In Tortilla Flat, I believe that phalanx can first be observed in action among Steinbeck’s paisanos as verbalized by the character Pilon, who expresses the group’s feeling that Danny, the “group caretaker,” has abandoned them. Characters like Danny—and later Doc and Fauna in Cannery Row—play the essential group-caretaker role ably articulated and applied in his work as an international management consultant by my friend James Kent, a Steinbeck lover of profound learning and understanding.

Pilon thinks that Danny is spending too much time with Sweets Ramiriz—the grateful recipient of the gift of a vacuum cleaner she can’t use—with the result that the group feels abandoned by their leader: “At first his friends ignored his absence, for it is the right of every man to have these little affairs. But as the weeks went on, and as a rather violent domestic life began to make Danny listless and pale, his friends became convinced that Sweets’ gratitude for the sweeping-machine was not to Danny’s best physical interests.”

The verbalized concern for Danny’s physical health is a rationalization—a banner-call to action—although its actual value-driven inspiration is jealousy about a relationship that has taken Danny away from the group. This distinction is important. In judging group or team behavior in business, logical rationalizations and value-judgments are significant factors in analyzing and predicting group or team actions; since they are functionally different, they require different responses. The distinction is revealed in Steinbeck’s description of the group’s decision to do something about the situation that confronts them: “Wherefore the friends, in despair, organized a group, formed for and dedicated to [Sweets’] destruction.”

As dramatized in John Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat, the phalanx is an unconscious complex within a group drawn together with a commonly-held objective by forces from within the collective unconscious. But the attempt to effectively influence the illusionary driving forces of a MOB or community—a common response by authority to such conditions around the world—remains, in practice, a mistake. Targeting the consciously stated objective rather than the unconscious motivation of the group wastes time, resources, and—when force is involved— human lives. Steinbeck learned about the collective unconscious from Carl Jung. We have much to learn about group behavior from John Steinbeck, starting with Tortilla Flat.

This is the first in Wesley Stillwagon’s series on the application of John Steinbeck and Carl Jung’s insights in innovative corporate training program design. To be continued.

In her new book, Carol and John Steinbeck, Prof. Susan Shillinglaw writes that “throughout the mid-to late 1930s, Ricketts “consulted Jungian therapist, Evelyn Ott …”. Prof. Shillinglaw continues her discussion and writes about another “female therapist, [Lucille Elliot], also a Jungian …”who visited Ed Ricketts and “found it a ‘relief” to be at the lab”. There is further discussion by Prof. Shillinglaw about Jung’s text Psychological Types. Allegedly, John Steinbeck and Evelyn Ott may have had a “brief and intense liaison …”.

Herb Behrens

To readers who visit the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas: Make it a point to meet Herb Behrens, the senior archivist, particularly if you have questions about John Steinbeck books, letters, or interviews. The Center serves as the repository for a large collection of primary source materials useful to a broad range of research on the writer’s life and work, and Herb knows where every item is located. Call the Center to make an appointment before you arrive. Herb is always busy but happy to help. Thank you, Herb!

I’ve talked to a few Monterey Jungians about Steinbeck-Analyst relationships and all were much too young to know any details. I think that I read that Steinbeck gave Evelyn Ott’s son boxing lessons at one time. Regarding the affair, knowing Steinbeck and the possibility of transference in such relationships, this is no surprise to me. LOL