Does John Steinbeck belong to English literature? Peter Ackroyd, one of Great Britain’s most prolific living writers, raised this question in my mind when I read Albion: The Invention of the English Imagination, a survey of the arts of the British Isles from Anglo-Saxon times to the present. Unlike Henry James and T.S. Eliot, native writers who defined themselves as Anglo-Americans, Steinbeck never claimed to be anything but an American author influenced by the English literature of the past. But Steinbeck’s ties to Great Britain were strong, his fiction flows from the well of English literature, and his temperament mirrored many of the English characteristics explored in Albion: The Invention of the English Imagination.

Does John Steinbeck belong to English literature? Peter Ackroyd, one of Great Britain’s most prolific living writers, raised this question in my mind when I read Albion: The Invention of the English Imagination, a survey of the arts of the British Isles from Anglo-Saxon times to the present. Unlike Henry James and T.S. Eliot, native writers who defined themselves as Anglo-Americans, Steinbeck never claimed to be anything but an American author influenced by the English literature of the past. But Steinbeck’s ties to Great Britain were strong, his fiction flows from the well of English literature, and his temperament mirrored many of the English characteristics explored in Albion: The Invention of the English Imagination.

King Arthur: John Steinbeck’s Magnificent Obsession

Thomas Malory’s King Arthur captured Steinbeck’s boyhood imagination and obsessed him throughout his life. In pursuit of this passion, Steinbeck traveled more extensively in Great Britain than anywhere outside the United States except Mexico and expended greater time and effort researching King Arthur than he did on any other project.

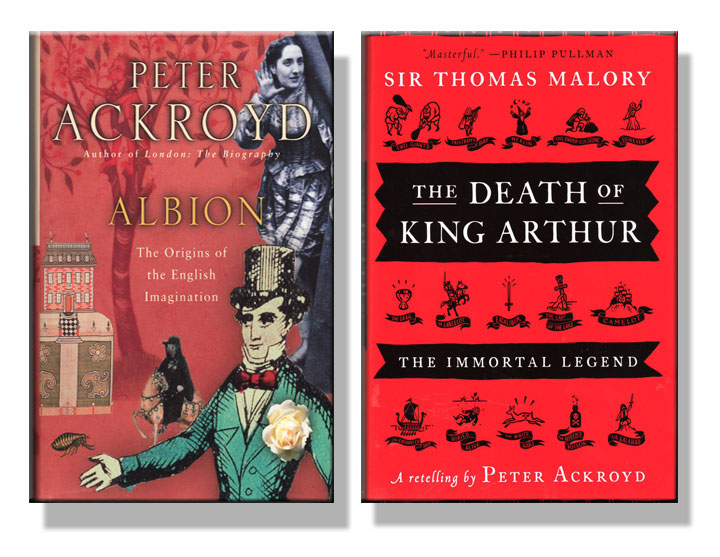

Steinbeck also loved English music. From the Tudor anthems of Thomas Tallis and William Byrd to the sea-sodden songs and symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams, the music of the British Isles inspired him when he wrote his novels and consoled him when he contemplated death. Although Steinbeck’s attempt to transpose the music of Malory’s Mort D’Arthur into modern English collapsed, King Arthur’s Round Table served as inspiration for some of his best writing, starting with Tortilla Flat, and Ackroyd includes Steinbeck in his short list of English writers most influenced by Malory and the King Arthur legend. (Ironically, Ackroyd’s adaptation of Malory’s King Arthur succeeds where Steinbeck failed. The opening sentence of The Death of King Arthur suggests why: “In the old wild days of the world there was a king of England known as Uther Pendragon; he was a dragon in wrath as well as in power.”)

It seems particularly appropriate to reflect on John Steinbeck’s Englishness today, his birthday.

But there is more to Steinbeck’s connection with Great Britain than love of King Arthur, English landscape, or the music of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Great Britain was in his blood, and it seems particularly appropriate to reflect on John Steinbeck’s Englishness today, his birthday.

The Invention of Steinbeck’s English Imagination

As indicated by the titles of In Dubious Battle and The Winter of Our Discontent, Steinbeck was inspired by English literature beyond Malory. Along with Shakespeare and Milton. John Bunyon and William Blake are notable influences, as well as the language of the King James Bible and the novels of Charles Dickens. But this obvious observation begs an interesting if unanswerable question. Was Steinbeck’s affinity for the British Isles, King Arthur, and English literature the root or the result of his Englishness? Was Great Britain in his blood before it was in his mind?

Was Steinbeck’s affinity for the British Isles, King Arthur, and English literature the root or the result of his Englishness? Was Great Britain in his blood before it was in his mind?

Steinbeck’s maternal grandparents were Scots-Irish immigrants, and his paternal grandmother was a Dickson from New England. He inherited his mother’s fascination with Celtic myth and magic. He dramatized his grandparents’ Calvinism and its conflicts in East of Eden. Whether inborn or acquired, the characteristics of Englishness described in Albion: The Invention of the English Imagination were present in Steinbeck’s thought and temperament and in his writing, from Cup of Gold to The Winter of Our Discontent, shaping his imagination and suggesting that he belongs to the tradition of English literature that began with Malory and Chaucer.

Were Steinbeck’s English traits the product or the source of his lifelong attraction to English writers and music?

Here are a few of the English traits identified by Ackroyd and shared by Steinbeck:

–A love of landscape and an attraction to the sea

–Antiquarianism, independence, and insularity

–Melancholy, fatalism, and the profession (if not the fact) of modesty

–Practicality, invention, and a love of science and experiment

–An insistence on privacy, solitude, and having a place of one’s own

–An instinctive belief in cultural continuity and “the presence of the past”

–A distrust of theology, abstraction, and fixed ideologies

–Creative translation, assimilation, and adaptation of earlier art

–A belief in ghosts, fairies, and magic (the Celts were British before they were Irish)

–A passion for home gardening, tinkering, and domestic self-help devices

–A penchant for portraiture in painting and an preference for character over plot in writing

–Making art organically, by accretion, rather than structurally by system, theory, or plan

–Moving between fiction and fact, history and fantasy, when telling a story

Were Steinbeck’s English traits the product or the source of his lifelong attraction to English writers and music? Two examples may help answer the question.

Steinbeck, Vaughan Williams, and Blake

Although Ackroyd mentions Steinbeck only in connection with Malory’s King Arthur, the nature of Steinbeck’s Englishness can be deduced from the chapter Ackroyd devotes to Ralph Vaughan Williams, Great Britain’s most popular modern composer, and from Ackroyd’s book-length biography of William Blake, the early English Romantic poet and artist. First Vaughan Williams, then Blake:

–Like Steinbeck, Vaughan Williams displayed a characteristically English “detachment and reticence” about explaining himself or the meaning of his work: “He was not given to ‘probing into himself and his thoughts or his own music. We may say the same of other English artists who have prided themselves on their technical skills and are decidedly reluctant to discuss the ‘meaning’ of their productions. . . . It is, once more, a question of English embarrassment.”

–Like Steinbeck, Vaughan Williams was moved by the early English music of Tallis, Byrd, and Henry Purcell. Noting the “plangent sadness” of Great Britain’s national music since their time, Ackroyd describes the songs and symphonies of Vaughan Williams as, like The Grapes of Wrath, “comparable to ‘the eternal note of sadness’ which Matthew Arnold heard on Dover Beach. . . . [a] note of quietly and insistently ‘throbbing melancholy’. . . .”

–Like Steinbeck, Vaughan Williams discovered universal meaning in local sources: “He believed that ‘if the roots of your art are firmly planted in your own soil and that soil has anything to give you, you may still gain the whole world and not lose your own souls.”

Like Steinbeck, Vaughan Williams discovered universal meaning in local sources.

–Although Steinbeck, like Blake, was baptized in the Episcopal church, his family’s religious roots were Lutheran, Calvinist, and—like those of Blake—Separatist. Jim Casy echoes Blake’s language (“Everything that lives is holy”) in The Grapes of Wrath. Steinbeck reflected Blake’s radical Protestant politics in his life: “The nature of Blake’s radicalism was perhaps not clear even to Blake himself . . . . But the fact that he never joined any particular group or society suggests that his was, from the beginning, an internal politics both self-willed and self-created.” Like Steinbeck, Blake “managed to combine an intense visionary belief in brotherhood and the human community with that robust and almost anarchic individualism so characteristic of London artisans” of his day.

Like Steinbeck, Blake ‘managed to combine an intense visionary belief in brotherhood and the human community with that robust and almost anarchic individualism so characteristic of London artisans’ of his day.

–Steinbeck and Blake shared a view of Mob Man as both infernal and godlike in power. A handbill for the Gordon Riots of 1780, which Blake experienced firsthand, “depicted the mob as ‘persevering and being united in One Man against the infernal designs of the Ministry.'” In Dubious Battle presents Steinbeck’s version of Group Man in Doc Burton’s observation that “[a] man in a group isn’t himself at all; he’s a cell in an organism that isn’t like him any more than the cells in your body are like you.” Like Blake, Steinbeck’s character concludes that Group Man can ultimately be perceived as God.

Like Blake, Steinbeck’s character concludes that Group Man can ultimately be perceived as God.

–Steinbeck and Blake shared the ability to transmute moral indignation into poetry. As Ackroyd notes, the chimney sweeps in Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience reflected contemporary reality: “They finished their work at noon, at which time they were turned upon the streets—all of them in rags (some of them, it seems, without any clothing at all), all of them unwashed, poor, hungry.” The starving children of The Grapes of Wrath were equally real; Steinbeck reported their plight in a San Francisco newspaper series before rendering them unforgettably in his novel. English child indenture was ended by an act of Parliament. California migrant starvation was alleviated by federal relief. But Steinbeck’s children, like those of Dickens and Blake, continue to haunt and horrify to this day. Among American writers since Harriet Beecher Stowe, it might be added, only Steinbeck possessed the power to change society by opening hearts, a defining characteristic of English literature since Blake and Dickens.

Steinbeck and Blake shared the ability to transmute moral indignation into poetry. . . . Among American writers since Harriet Beecher Stowe, it might be added, only Steinbeck possessed the power to change society by opening hearts, a defining characteristic of English literature since Blake and Dickens.

In a forgotten episode of literary history, certain late-19th century professors of English literature at American colleges such as the University of North Carolina, where I studied, advocated that the United States rejoin Great Britain to form a cultural, if not political, affiliation. Their heads were in Chapel Hill, but their hearts were in Chaucer. Yet in their time it could be argued that American writing remained subservient to English literature. While reading Peter Ackroyd, it pleased me to consider that John Steinbeck, the most American of American writers since their era, may have fulfilled their desire more convincingly than James, Eliot, and other American-Anglophile authors. Like the music of Vaughan Williams and the art of William Blake, Steinbeck’s writing expresses Englishness authentically, by staying rooted, looking inward, and achieving universality in a diversity of modes, from mythic to melancholy. These artists are, one notes, always sad, and the sea is always at their side.

Interesting piece, Will, and I am most intrigued by the line that only Steinbeck, since Stowe, “possessed the power to change society by opening hearts.” This can lead to a fascinating search of the power of various writers and artists to change the world around them. For instance, I think Tennessee Williams and Ken Kesey through “Suddenly Last Summer” and “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” powerfully changed the dark and hidden world of mental health care of their time (shock treatments, lobotomies, over-medication), and it was done through these two works opening hearts. Is mental health also society? Well, certainly a part of it. Much as “The Grapes of Wrath” changed the world of labor, and then went beyond. Thanks for the intriguing subject.

Mental health awareness is certainly a social cause, and Ken Kesey opened eyes all over the world to the comic possibilities. However, I would hesitate to say that his wonderful book (and movie), or the dark vision of the Tennessee Williams novel-film, exerted the earnest influence for political reform like that of Stowe around slavery or Steinbeck with regard to migrant labor conditions. Food for thought.

I don’t know, Will, I think they were both very powerful statements, and “.mental health” institutions became a way of putting people away, a way of silencing them. Easy to get in, difficult to get out. Williams wrote his play “Suddenly Last Summer” probably in some reaction to his sister Rose – Laura in the Glass Menagerie – being insttiutonalized, something he always felt guilty about. She outlived him.