Lily had a little antique and junk shop a half block off Main Street. She also had a thick head of wavy white hair that she brushed up and back like a lion’s mane. The store was as neat and clean as Lily herself, who shone with a healthy scrubbed look. Her strong jaw and high cheekbones were set off by distant, light gray eyes and straight white teeth.

Lily opened the shop shortly after her husband Len died from a stroke at age sixty-seven, and it became her life’s center. She went into the shop almost daily to fill the loneliness—sometimes, if the sadness was upon her, opening on Sundays after church. Lily’s shop traded in old furniture, tools and small farm implements, saddles and fancy bridles, quilts, and framed vintage photographs from the Victorian era. Glass cases contained old post cards, yo-yos, and Dell and DC comics.

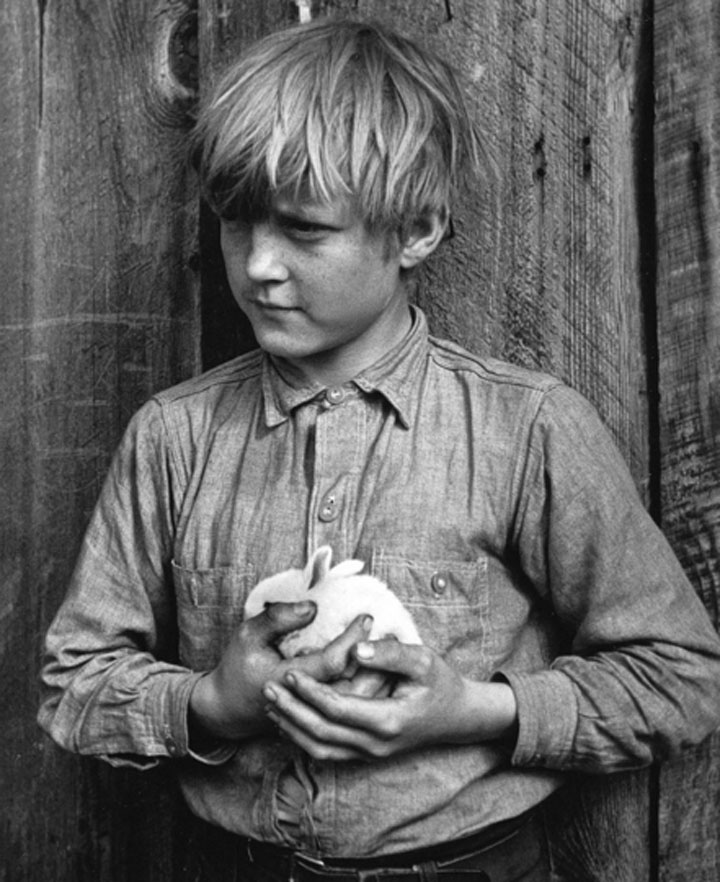

On the counter she kept a plastic container of red licorice sticks for five cents each. But when adults came in with children, she’d give the children a free licorice to keep them happy and allow their parents to browse. Anyway, she liked children. She even kept a full water bowl for dogs.

Now and then something valuable would come into the shop—a fine painting, a painted antique six-board chest, a rare piece of art glass, something like that. Lily was not lazy about researching such interesting acquisitions. If she thought it might be special but wasn’t sure, she kept it in the back room until she was. After all, hardly a day went by that a runner or picker didn’t stop in hope of picking off a valuable piece Lily had undervalued and thereby make a killing reselling it in San Francisco or Los Angeles.

Lily acquired some of her inventory at yard sales and farm bankruptcy auctions. But most of the merchandise came through the front door with people in need of money toting items important and dear to them.

Oddly, there was one item Lily didn’t want to see come through the door—books. She especially dreaded books by a particular author, yet they came in often because the author had not only been prolific, he had been born and raised—and so heavily read—in this very town, Salinas, in California.

Even if the seller didn’t have a book by that writer to sell to Lily, the possibility one of his books might be among the offerings invariably got her remembering again. This was something she didn’t want to do—it always led to a repeat of the series of nightmares that had haunted her in her younger years.

A telephone call had led to this dark incident, which would stay with Lily all her life, taking her back to a time in the late 1930s when there was to be a gathering, a reunion of thirty or so high school classmates. Two couples came up with the idea over too many beers at a bar in East Salinas; tipsy, they made late-night phone calls, and the event was set.

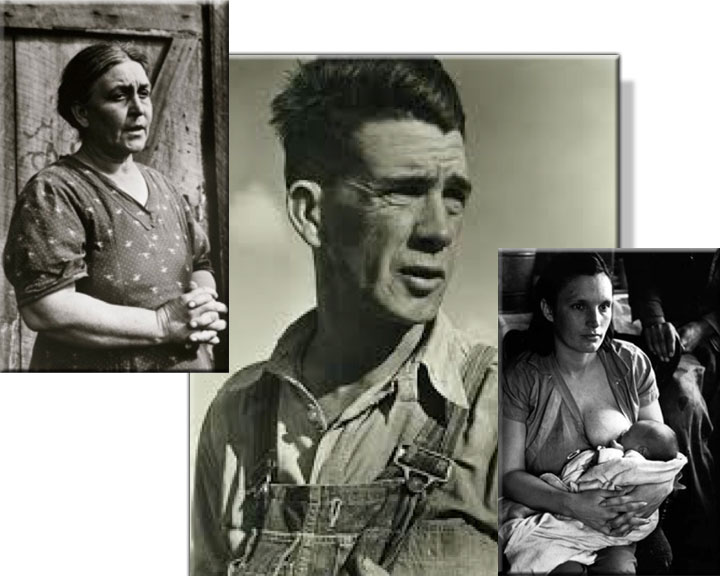

The reunion was to be held in a town park on a spring Sunday afternoon. They would eat and drink and talk about what had been going on in their lives. The participants wanted the writer John to be a part of the gathering. He had, after all, been a member of their graduating class. But John had not been seen in Salinas since his parents died.

“He thought there were people in Salinas who might do him harm because of what he wrote and was writing, which is one reason he lived over on the coast. At least that was the story,’’ Lily told a listener decades ago, just a few years before her death in the very chair in which she sat recalling the incident.

“To tell the truth, we felt John had deserted us for those snooty coast people and we were hurt. The folks here have long resented those folks on the coast with their golf courses and big houses and ocean views while over here we lay down manure and grow most of their food for them. I can tell you that the animosity was especially deep in those days.’’

Lily was probably closing in on ninety at the time she told her story. She was sitting at her desk, the sun shining through the shop’s front window, remembering. As she spoke, she absently watched the cars passing by.

“John and I had been close in high school, not sweethearts or anything, you understand, but we liked each other and kidded around a lot. We were both big, awkward kids, maybe that had something to do with it. He was a big fellow, I was a big girl. He called me Lil’. He was a funny guy, fun to be with, not so serious as people made out.

“Anyway, everyone said, `Lily, you call him, you call John and tell him about our little get-together reunion, he will listen to you. You can talk anyone into anything.‘ And that was almost the truth—I can be pretty damn persuasive. `If you tell him he should come, then he will. Remind him he was our class president and we want him here. It’s only right.’

“So I called his house on the coast and Carol answered—she was his first wife and didn’t know me from boo—and she seemed pretty suspicious, maybe because I was a woman and everyone said back then I had a sexy voice, so someone who didn’t know me might actually think I was pretty. Word was John and Carol were on the outs, or close to it. Well, she didn’t have to worry about me. I was not pretty and I was perfectly happy with my Len.

“When I told her why I was calling she said she didn’t think there was much chance of John coming to Salinas, but she put him on the phone anyway. He said, `Hi, Lil’, how are you?’ He was cautious at first and that surprised me because it wasn’t like the John I knew. But as we chatted he loosened up and we started talking about high school and that stuff.

“He even asked about Len and our kids and I asked him about his writing, which of course we had all been reading about in the newspapers anyway. He said to forget those stories, it was all balderdash, he was still struggling and, if he had his way, would always struggle because it was good for him. When I steered the talk to how things were going in Salinas, he got real quiet real quick.‘’

Lily paused for a moment, nervously rubbing her hands together. She continued reluctantly, not looking at her listener.

“Well, so then I got around to telling him why I called, you know, the reunion and all. He said right away, `Sorry, Lil’, I can’t make it. Thanks for asking.’ But just like me,’’ she added ruefully, “I kept after him.’’

“I said, `John, we all know you think people are mad here about what you’ve been saying and writing, about the field workers and the working conditions and all, but we think you’re imagining a lot of it. Sure there are some crabby people, a lot of old curmudgeons so dried up they can’t spit, and some selfish growers just after the buck, but frankly most of us agree things need to be better. We don’t think you should let the crabby ones keep you away. It’s your home too after all.’

“Well, he still resisted, said it wasn’t that . . . though we all knew it was. So I played my hole card; I played to his ego. I told him we were all excited about his success and wanted our wives and husbands and children to meet the famous writer we’d gone to school with, and maybe at the same time he’d like to keep up with what all of us were doing.

“Of course nobody was writing anything about us, but most of us were doing OK. My husband Len’s western wear store was doing very well, for one. John was excited about that. He said, `Good old Len, he has always had the eye. He picked you out, after all. You’ll soon be rich, Lil’. I predict it.’ ‘’

Lily looked around the shop.

“Len’s store was in this very space, did you know that? The place back then was called Len and Lily’s Western Paraphernalia Store. Len picked that unwieldy name paraphernalia on purpose—he said it would encourage people to use their dictionaries. And once they got the word paraphernalia in their heads they’d always think of us. We did very well, so maybe he was right. When Len died I kept the space, but it wasn’t long before I turned it into this shop because I didn’t like dealing with haberdashery wholesalers—that was Len’s job. I’ve always loved old things anyway. Kept the same sign and had Western Paraphernalia Store painted out and Antiques and Etcetera Shop painted in so it says Len and Lily’s Antique and Etcetera Shop. I figured people could look up etcetera just like they looked up paraphernalia. Anyway, etcetera covers a lot of things.’’

Lily started to light a cigarette, but her hands were shaking so she dropped the idea and set the cigarette and lighter on the desk.

“Len would laugh if he could see he’s dealing in antiques now. Well, we still have some western things, like that hand-tooled saddle in the window, and now and then I buy a nice rhinestone shirt or beaver Stetson from a broke cowboy, and there are plenty of them around.’’

Lily stood slowly and walked to a worn velvet burgundy curtain that divided the shop from a back room. She turned and said, slowly and sadly, “I don’t know if I could count how many times I wish John had said no to me and hadn’t made it to the reunion. But he didn’t say no and he did come and you can’t take any of it back once it happens. Amazing how long in life it takes us to figure that out.’’

Then she disappeared through the curtain, returning minutes later carrying a shoebox tied up with string. She was breathing heavily. “I had to reach up high,’’ she explained. “Need to buy a ladder.’’

Lily set the box on her desktop, snipping the string with a pair of scissors and pulling out a handful of old photographs. She handed them carefully to her listener.

“Those are photographs of the reunion. They’re faded but you can still make out children playing tag or hide ‘n seek, adults drinking and eating. Must have been forty of us at final count. You can spot John in three or four of those, big guy with big ears, holding a beer. And he was happy when those pictures were being taken—about his next book, about seeing people he liked, including Len and me I hope.

“I think the only thing he wasn’t happy about was Carol. He hadn’t brought her even though we wanted her to come. Maybe he left her behind because he was worried about her safety. He knew there was a risk. But he didn’t seem nervous like he‘d seemed over the phone. I think those beers he had probably helped. And I think he believed me. I think he thought if I said it would be alright, it would.’’

Lily closed her distant gray eyes for a moment and said, “But it happened anyway.’’

“What happened?’’ her listener asked after a few moments of silence.

“Well, the white truck,’’ said Lily. “The white pickup truck happened. Came out of nowhere, a white Ford pickup truck. Jumped the curb onto the picnic grounds. A truck with big headlights like cartoon eyes. You used to see them up and down the valley. Everyone had one. I’ll never forget those headlight eyes coming at us even though it was still daytime and the street lights weren’t on. It seemed like a living thing. I think we all sensed what it was, especially John. The bastards could have killed a child. I think about that, what might have happened to a child all because of a telephone call I made.’’

“They were after John?’’

“Oh, yes. Oh yes, oh yes. They must have known ahead of time. I always wondered about that, how they knew—still do. There were two of them. The one with a gun, a revolver, threw John against a tree with the gun under his throat. Len moved in, some of the other men, but by then it was too dangerous, what with the gun at John’s throat, so they backed off.

“The one without the gun, he said, `You write one more ‘effin word about field workers and we’ll blow your ‘effin head off!’ John’s face was red and he was clenching his fists and we all yell at one time, I don’t know how it happened but we did, as if we’d rehearsed it for a week, `John, don’t move! Don’t move a muscle!’ Then Len said, stepping up, `We know you boys, anything happens to John . . . . ‘

“And they screamed at Len he was an ‘effin moron just like John. But they wouldn’t have said that if they hadn’t had a gun, no sir, and everyone knew it. Len would have mopped up the fairgrounds with them. And they knew that too. So they pushed John back and got in the truck and drove away real quick.’’

Lily’s hands were shaking from the memory, but she lit her cigarette anyway and again looked out the window at the cars passing by.

“So that’s what happened more or less,’’ she said finally.

“Did Len really know the guys?’’

“That was an inspiration by my Len. Nobody knew them. They were hired thugs, that’s all. But Len put the worry in them. Maybe saved John’s life.’’

“You notify the police?’’

“We wanted to, but John said no, he didn’t want us to, he already had enough troubles with crooks and growers and the law. Anyway, the Salinas law didn’t like him, and what were we going to say anyway? ‘Two guys we never saw before in a white pickup truck like a hundred others. Oh, and officers, nobody got a license number either!’ So we gathered our kids around us and sat quietly for a while, calming John with one more beer, him apologizing to everyone like it was all his fault.

“Next day, a Monday, guess what John did? Applied for a gun permit—in Monterey, not Salinas.’’

“Did you ever see John again?’’

Lily looked at the man and then at the front door of the shop.

“Sure, all the time, honey. Still do see him in fact. See him in my nightmares after someone walks through that door with a pile of books. I’ll see him tonight for sure.’’

“Lily” is one of a series of short stories being written by Steve Hauk based on little-known but dramatic events in the life of John Steinbeck. The stories are inspired by actual incidents, but characters and events are added, as in any work of fiction. There are some exceptions, pure surmises based on anecdotes and reminisces, such as “John and the River,” in an attempt to capture character. Steve’s working title for the collection of short stories is “Almost True Stories from a Writer’s Life.”