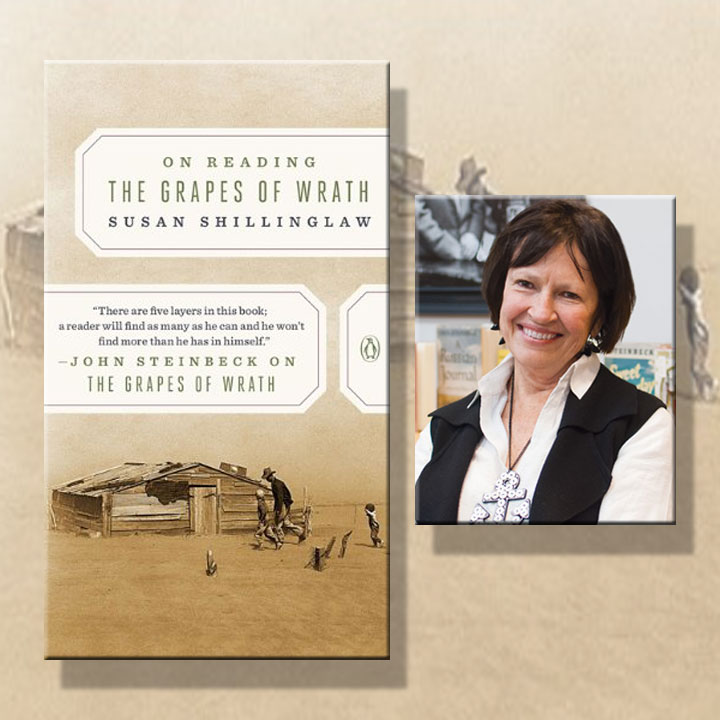

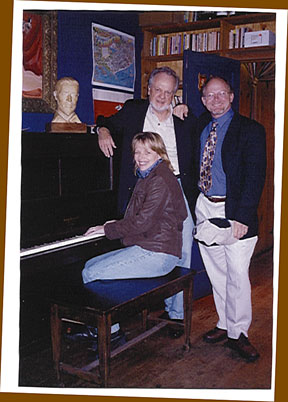

From Woody Guthrie to Bruce Springsteen, two books that made John Steinbeck famous—Tortilla Flat and The Grapes of Wrath—have inspired American singers to celebrate both sides, sunny and sad, of John Steinbeck’s moody populism. Aaron Copland wrote orchestral music for The Red Pony and Of Mice and Men in the 1940s, and Ricky Ian Gordon’s operatic setting of The Grapes of Wrath premiered in 1977. But before now pipe organs have been silent on the subject of John Steinbeck, and that seemed strange: the author listened to Bach and had an ear for church music developed as a child. The February 16 premiere of Franklin D. Ashdown’s monumental Steinbeck Suite for Organ at Mission Santa Clara—65 miles from Steinbeck’s hometown of Salinas—remedied this historic oversight. Pulling out all the stops on the reverberant Mission Santa Clara pipe organ, James Welch brought passages from Tortilla Flat and The Grapes of Wrath chosen by Ashdown to thundering and whispering life. Five movements describe moments of high drama from two Steinbeck classics: I. Perambolo (“The Humanity of John Steinbeck”); II. Divertimento (“Making Camp and Celebrating on Route 66: The Grapes of Wrath”); III. Miserere (“’If you’re in trouble or hurt or need—go to the poor people. They’re the ones that’ll help’: The Grapes of Wrath”); IV. Musica de los Paisanos (“’How lonely it would be in the world if there are no friends to sit with one and share one’s grappa’: Tortilla Flat”); and V. Toccata (“The Conflagration of Danny’s House: Tortilla Flat”). Crank up the volume on your computer, then listen, laugh, and weep. The live recording below is courtesy of Santa Clara University and includes movement pauses and audience applause.