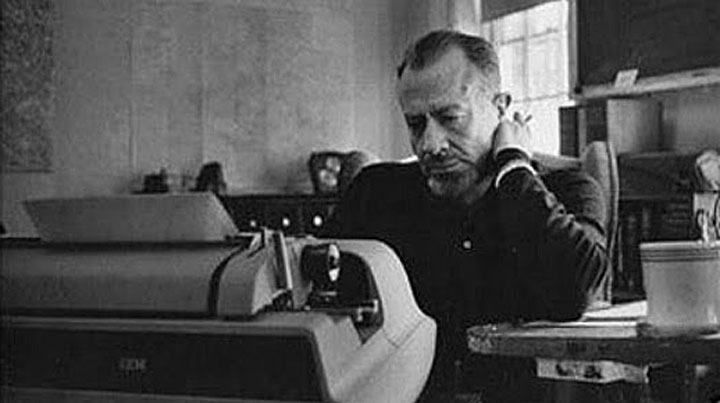

How to write well? Some writing tips enter our consciousness formally, through the classroom door. Others arrive surreptitiously, as editors unseen hover over our hands on the keyboard. But writing tips also slip through a half-open window of the struggling writer’s mind, appearing as a bright passage in a book or needed words of encouragement from a colleague that learning how to write well is a craft worth pursuing for yet another day. John Steinbeck’s writing tips took the second and third forms.

How to write well? Some writing tips enter our consciousness formally, through the classroom door. Others arrive surreptitiously, as editors unseen hover over our hands on the keyboard. But writing tips also slip through a half-open window of the struggling writer’s mind, appearing as a bright passage in a book or needed words of encouragement from a colleague that learning how to write well is a craft worth pursuing for yet another day. John Steinbeck’s writing tips took the second and third forms.

For writers like me, Steinbeck’s books and letters are a window on how to write better that never closes.

For writers like me, Steinbeck’s books and letters are a window on how to write better that never closes. Like us, he understood that every lesson on how to write more effectively, however small, is a gift for today and for tomorrow. As Jay Parini notes in John Steinbeck: A Biography, “[John Steinbeck’s] didacticism would become an integral part of his profile as a man and writer . . . .” His lessons on how to write, whatever the context or occasion, remain a source of inspiration, instruction, and delight in my life as a writer.

The Steinbeck Model in Writing Tips from Roy Peter Clark

In the opening pages of Writing Tools, a book of writing tips by Roy Peter Clark that I highly recommend, John Steinbeck appears as a model of how to write well. Clark quotes this passage from Cannery Row as an example of the way master writers like Steinbeck “can craft page after page of sentences” by relying on simple constructions of subject and verb:

He didn’t need a clock. He had been working in a tidal pattern . . . . In the dawn he had awakened . . . . He drank some hot coffee, ate three sandwiches, and had a quart of beer.

Clark notes that “Steinbeck places subject and verb at or near the beginning of each sentence” in the example offered:

Clarity and narrative energy flow through the passage, as one sentence builds on another. He avoids monotony by including the brief introductory phrase . . . and by varying the lengths of sentences, a writing tool we will consider later.

Clark notes that ‘Steinbeck places subject and verb at or near the beginning of each sentence’ . . . .

A respected resource at The Poynter Institute on how to write better journalism, Clark returns to John Steinbeck in his list of writing tips, noting that in Travels With Charley Steinbeck uses passive verbs “to call attention to the receiver of the action” at just the right time.

“The best writers make the best choices between active and passive,” explains Clark:

Steinbeck wrote, “The night was loaded with omens.” Steinbeck could have written, “Omens loaded the night,” but in that case the active would have been unfair to both the night and the omens, the meaning and the music of the sentence.

John Steinbeck’s Advice to Hugh Mulligan on How to Write

A journalist for much of his life, Steinbeck sometimes applied sideways humor to prop open the how-to-write window, a trait noted by the late Hugh Mulligan, a veteran reporter covering the war in Vietnam when Steinbeck was there. In his book The Journalist’s Craft, Mulligan states that he is writing “a nuts-and-bolts book about writing, but before I attempt to get down to the basic hardware, I should note that history is rife with confusion on this subject.” Enter Steinbeck, laughing.

Later in his collection of writing tips Mulligan quotes Somerset Maugham, the English writer who was born 28 years before John Steinbeck but died only 12 months earlier than his celebrated American counterpart:

[T]hat elegant master of the Queen’s English . . . told a BBC interviewer: “There are three basic rules to good writing. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are” . . . . I mentioned this to John Steinbeck one night in Saigon during the Vietnam War . . . . The Nobel laureate took a stab at filling in the blanks for Maugham: “Never make excuses. Never let them see you bleed. Never get separated from your luggage.” He then added a fourth: “Find out when the bar opens and when the laundry comes back.”

Speaking as a writer who has lost his notes, a bit of his virtue, and a sport coat or two on reporting assignments, I find practical wisdom woven into Steinbeck’s mordant wit. If you write for a living and don’t find yourself grinning at this advice, you might consider taking up another profession. Your absence may be missed, but not by other writers.

Maria Povova’s “6 Writing Tips from John Steinbeck”

Fifty years after their conversation, the Internet has expedited and amplified the writing tips shared by John Steinbeck with Hugh Mulligan in Saigon. While roaming the digital byways recently, I came across Maria Povova’s “6 Writing Tips from John Steinbeck,” a set of principles on how to write well gleaned from her reading of a 1975 Paris Review article and recent Atlantic magazine blog.

Call my online discovery software-supported serendipity if you like. But Steinbeck’s advice has outlasted the manual typewriter and will no doubt survive smartphones as well.

Steinbeck’s advice has outlasted the manual typewriter and will no doubt survive smartphones as well.

Here are my favorite writing tips from Povova’s piece:

Write freely and as rapidly as possible and throw the whole thing on paper. Never correct or rewrite until the whole thing is down. Rewrite in process is usually found to be an excuse for not going on. It also interferes with flow and rhythm which can only come from a kind of unconscious association with the material.

If you are using dialogue—say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.

Forget your generalized audience. In the first place, the nameless, faceless audience will scare you to death and in the second place, unlike the theater, it doesn’t exist. In writing, your audience is one single reader. I have found that sometimes it helps to pick out one person—a real person you know, or an imagined person—and write to that one.

When he talked about how to write, John Steinbeck always addressed other writers—even if he was the imagined writer he had in mind.

When he talked about how to write, John Steinbeck always addressed other writers—even if he was the imagined writer he had in mind. The process could be painful, and Steinbeck sometimes had to remind himself to follow his own advice. After the announcement in 1962 that he had won the Nobel Prize, he admitted how hard it was to write his acceptance speech in a letter to Dook Sheffield, a college friend and fellow writer:

I wrote the damned speech at least 20 times . . . . Last night I got mad and wrote exactly what I wanted to say. I don’t know whether or not it’s good but at least it’s me.