John Steinbeck invited his readers to participate imaginatively in his fiction. James Kent, a consultant and community organizer, has responded with inspired ingenuity, applying life lessons learned from Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row in his consulting career. Doc’s Lab: Myth & Legends of Cannery Row, a collection of real-life Cannery Row profiles by the late Ed Larsh, describes how Kent used one method—modeled on the group dynamics of Mack and the Boys—to resolve an issue of survival for the community of Minturn, Colorado. Kent’s recent post on John Steinbeck’s social ecology stimulated so much interest that we wanted to share Larsh’s chapter on Kent’s methods as well. Doc’s Lab is out of print, but we requested and received permission to reproduce “Mack and The Boys as Consultants” from Kent, Larsh’s successor at the nonprofit organization that published Larsh’s book in 1995. The colorful cover art depicting Doc’s lab and its denizens is by the late Eldon Dedini, a magazine cartoonist and modern Cannery Row figure who was born in King City, California, and lived in Carmel.

Cannery Row’s Mack and the Boys as Consultants

Pascal Covici, Steinbeck’s editor for the novel Cannery Row, stated that Cannery Row was written on four levels and that “no critic has as yet stumbled on the design of the book.”

Had Steinbeck been a futurist instead of a great writer, he might have predicted the discovery of the novel’s design to occur in the year 1971 in a small town in Colorado called Minturn.

In the summer of 1887, the Denver and Rio Grande Western built a railroad from Pueblo, Colorado, to Leadville, Colorado, where the silver mines were producing millions of dollars in carbonated ore. The Denver and Rio Grande Western then continued to construct its line over the continental divide, from Leadville to the western slope of the United States and down the Colorado River basin to access Aspen, another flourishing mining town, and then on across Utah to the Pacific’s Eastern Rim. But first you had to have great coal-fired steam engines called “mallots” to pull the trains over Tennessee Pass, which was very near Leadville. Once you got the trains on top of Tennessee Pass it was all down hill. Except if you were going the other way. Then you had to add four or five of the largest engines ever built to the train at a little town called Minturn, Colorado. It was up hill over the continental divide all the way from Minturn to Leadville, a town which sits at 10,200 feet.

Leadville, Colorado, where I was born and raised, is not an easy place to live. My mother, who lived there her entire life, always wanted to move. She would have moved anywhere—anywhere, that is, except to Minturn.

Had Steinbeck been a futurist instead of a great writer, he might have predicted the discovery of the novel’s design to occur in the year 1971 in a small town in Colorado called Minturn.

Minturn, however, does have a colorful, romantic, and traumatic past. The ancestors of many of the Hispanics who were living in Minturn in 1971 came into that high mountain valley 300 years ago. The conquistadors came north from Santa Fe in the 17th century, bringing with them sheep and sheep herders. These sheep herders settled in the upper Eagle Valley of Colorado. The Denver and Rio Grande Western railroad in 1887 was in need of cheap labor. They found it in the Hispanic village called Minturn. The railroad hired the Hispanics as section hands and gandy dancers, a radical cultural and career change—sheep herding to working on the railroad. The workers were 95% Mexican-Indian immigrants; they were Catholic, prolific, hard working, gentle, beautiful people. They erected small wooden houses along the Eagle River, a natural watershed for the high, snow-covered Rocky Mountains. The clear, crystal mountain water cascaded down through deep gorges into the Colorado River Basin.

Two miles above Minturn the river, on its way to the sea, flows through a steep canyon. It passes beneath the crest of Battle Mountain where, near the top but deep underground, rested a large deposit of zinc. And as the Twentieth Century arrived, so did the New Jersey Zinc Mine. The absentee mine owners built a company town for the Hispanic laborers. They called the town Gilman and placed it at the edge of the precipice. The closest structures to the precipice were the outhouses. The Zinc Mine then built a mill on the site, and by diverting the higher water were able, by gravity, to wash the tailings of the mill into the once-clear river some 1,500 feet below. All of this disturbance took place only a few hundred yards from where the ancient river flowed through the Hispanic town of Minturn, and where the shiny new rails carrying the giant coal-fired steam engines were belching black cinders over the freshly washed sheets that the Hispanic women hung dutifully over their clothes lines.

For those of us who were in the far reaches of the Pacific Ocean at the end of the war in the fall of 1945, when Cannery Row was first published, there was a driving necessity and a compelling dream to go home. I have a strong feeling that it didn’t matter whether home was in Brooklyn, New York, Beverly Hills, California, or small towns in Colorado. Or whether you were Sicilian-Americans from New Monterey, White Anglo-Saxons from the Midwest, African-Americans from the South, or Spanish-Americans from Minturn. We all wanted to come home.

Many years later, while working for the U.S. Department of Education in Washington, D.C., I was asked to investigate a small town in Colorado called Minturn regarding some educational issues involving a large number of Hispanic immigrants. I was told that there was something going on involving the national forests and a large developer who was expanding the ski industry.

That was my first introduction to Jim Kent, a community organizer and private consultant. We met for the first time in a saloon called The Saloon in Minturn, Colorado.

Jim Kent, Ed Ricketts, and Lessons from Doc’s Lab

Jim Kent is an applied sociologist who brings to his work the wisdom found in everyday living. Jim was born and raised in the northern mountains of Appalachia, where family networks are essential to everyday survival. He discovered the dynamics of social action through Steinbeck’s Ed “Doc” Ricketts, and he has applied this knowledge with success all over the world.

The story of Minturn, as Jim Kent tells it, is the story of ordinary people discovering that their lives were changing and wondering what they could do to preserve the things they knew and loved. In more dramatic terms, they discovered how to save themselves from being destroyed. Now, some 24 years later, the people of Minturn, Colorado are still there, in a sense, because of the influence of Ed Ricketts and John Steinbeck. The issue for Kent was how to have the people discover the need to save their way of life, and a method to accomplish this, and he found the answers in fiction.

Minturn in 1971 had been in the path of the Vail ski-area expansion. Vail Associates, owners of the ski area, wanted to turn Minturn into a fancy resort town to service a new mountain which they called Meadow Mountain, and then to build on federal land in the national forests (all of which required environmental impact statements).

There is a large hill near Minturn that is referred to as Aveja Colina, a Spanish name meaning “sheep hill,” evidence of generations of a Spanish influence in the area.

That, essentially, was the context; a 19th century mining town facing a 20th century recreation machine intent on changing and developing not only the town, but the mountains and forests surrounding it.

Jim was born and raised in the northern mountains of Appalachia, where family networks are essential to everyday survival. He discovered the dynamics of social action through Steinbeck’s Ed ‘Doc’ Ricketts, and he has applied this knowledge with success all over the world.

Jim Kent came to Minturn to see what might be done to face this enormous challenge of dealing with major changes in a manner that might prevent the people from losing their culture. After a few weeks spent with the local dwellers of Minturn, Jim realized that formal organizational techniques would not work; that if the people did not create a different mechanism to work within the cultural context of their community, they would indeed lose out to the overwhelming forces coming from outside.

As a basis for Kent’s organizational work, he reached deep into the story of Ed Ricketts, as told by John Steinbeck. Jim worked in the Eagle Valley from 1971 to 1979. His story has a very successful and exciting ending.

The story Jim told me is, in essence, the story of how he moved from fiction to reality, from Steinbeck’s fiction of Cannery Row, through the understanding of Ed Ricketts’ ecological theory, and finally to the solution of a modern social problem. He had to go beyond Steinbeck’s Cannery Row to The Moon Is Down, a book Steinbeck wrote in 1943 for what was to become the CIA. What Steinbeck reported in that book concerned an informal process whereby the citizens of a Norwegian town networked together to deal with Nazi Germany’s occupation of their land. Essentially, the people, through their informal networking, drove the German occupiers into frustration. By the simple means of shunning them, by not looking them in the eye, and by not asking them questions—by not engaging them in any way—they literally controlled the situation, even though they were occupied. That was what Kent was looking for in Minturn. How could the people participate in and control the situation in the face of a very strong outside alien force, a force that to them was not unlike the occupation forces in wartime Norway?

Cannery Row, The Moon Is Down, and Minturn, Colorado

The book Cannery Row was the civilian counterpart of The Moon Is Down. It literally took the informal system that Steinbeck describes in The Moon Is Down and connected it to place, to the working fishing community known as Cannery Row. Networks led by Mack and the Boys, and exchanges that took place in Ed Ricketts’ lab, dealt with moral conflicts and with ideological conflicts very similar to those dealt with in Norway.

What is important, though, is to note that The Moon Is Down was so powerful that when the manuscript of the story was found by a German trooper, the person on whom it had been found was summarily executed. Revealing the power of the informal network, The Moon Is Down ultimately became a handbook for the French, Norwegians, and others engaged in guerrilla warfare. Steinbeck, in writing Cannery Row, was able to describe the process of intelligent resistance in a very humorous, but significant form.

Jim Kent understood that once you can interact with your environment, you can then choose from your culture what you need to keep and what you can safely discard. If you cannot interact with your environment, and it is controlled by outsiders, then you will systematically lose your culture and lose your sense of place.

Empowerment came through the rich descriptions in Steinbeck’s novels, and that became the primary criteria for Kent’s base of networks and operations in Minturn.

Kent explained:

“If you believe in process rather than product, you work with ideas that come from the people, or from discussion with the people, ideas that are generated in the informal gatherings of society. Ordinarily, in formal situations, organizers take the point and the lead and later learn that the people they were leading became powerless once the organizers have left. My mode of operation, what I learned from Steinbeck and Ricketts, was to deal with the essence of leadership; not to come on as an authority, but to help the people feel ownership through a leadership style, utilizing a discovery process. In Minturn, we had a chance to apply Ricketts’ and Steinbeck’s social action design, the thing that had been projected in novel form, and convert it into a real-life setting.”

Descriptions in networks, according to Kent, can prevent the dissolution of a culture. The process can also assist the participants to accommodate change. The key concepts, if change is going to work, are participation and ownership.

Networks led by Mack and the Boys, and exchanges that took place in Ed Ricketts’ lab, dealt with moral conflicts and with ideological conflicts very similar to those dealt with in Norway.

Kent learned, from Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, a social-ecological approach that would be non-teleological. What gave Jim a license to intervene was the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, which governed Environmental Impact Statements. It declared that developments must maintain the harmony of the physical, biological, social, and economic environments. So Jim for the first time was attempting to put into practice the social aspects of Ricketts’ theory. And also for the first time, the design and levels of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row could come to life for the average reader as a process for celebrating life rather than as just a work of fiction.

Richard Astro, who wrote a very good book called John Steinbeck and Ricketts: The Making of a Novelist, gives us a major insight into how this came about. In the last paragraphs of Astro’s epilogue he writes: “It is clear that the artist rarely operates in a vacuum. And with Ricketts’ world-view accessible to him, we may be thankful that Steinbeck chose not to write all his books in isolation.”

By analyzing the range and depth of Ricketts’ impact on Steinbeck’s fiction, one may see Steinbeck’s accomplishments as a writer with fresh perspective. The novelist’s philosophy of life is not tenth-rate, and his social and political material is not worn and obsolete. In his best works, Steinbeck fused science and philosophy, art and ethics, by combining the broad vision and compelling metaphysic of Edward F. Ricketts with a personal gospel of social action. In his own time and with his own voice, John Steinbeck defined and gave meaning to the uniquely complicated nature of the human experience.

Kent said:

“Steinbeck allowed us to see life in its broadest function in one place through Cannery Row. We had to see it all, not just one part of life as Steinbeck portrayed it. We had to see total life for Danny, in Tortilla Flat, or for Mack and the Boys. Steinbeck, of course, got the vision from Ed Ricketts, the marine biologist who, upon looking into a tide pool saw it as microcosm of the universe. As for us, we were looking at the dynamics of a small community called Minturn; at how it functioned as a dynamic universe through the people’s understanding of their own natural state. This was our way of maintaining a universe as a whole, not as fragmented parts.”

I asked Jim Kent what he meant earlier when he had said that his discovery process dealt with “descriptions.” He replied:

“Descriptions have to be disciplined by the describer being a stranger. You must be able to see what was happening by observing and by listening with your whole nervous system, rather than by just hearing the words. The describer must be reflective in order to reflect back to the people their own content, to understand the power of their words so that they could bring about change in their context. Those were key qualities of Ed Ricketts: a willingness to listen as a stranger and to reflect.”

As an organizer, Jim Kent was emulating Doc in Cannery Row.

Steinbeck allowed us to see life in its broadest function in one place through Cannery Row. . . . As for us, we were looking at the dynamics of a small community called Minturn; at how it functioned as a dynamic universe through the people’s understanding of their own natural state. This was our way of maintaining a universe as a whole, not as fragmented parts.

In mining towns on a Sunday, everybody is out either on the street or in the parks with their families. So one of the first descriptors Kent discovered was the dynamics of Sundays in Minturn. In mining, there are three shifts: days, swing shift, and graveyard. Each shift is eight hours. Therefore, there is very little time to socialize except on the one day when the mine is closed down, Sunday. Kent was able to get a picture of Minturn from having read Cannery Row. He was able to track on the notion of gathering, and where people gathered. On Cannery Row, it was Ed Ricketts’ laboratory. In Minturn, it was the meat counter of the Super Food Store, where Bob Gallegos held forth. Gallegos was like Ed Ricketts. He was a philosopher with a concept about life which was very complete, very exciting. It was different from, but also similar to, Ed Ricketts’ holistic ecological theories.

People would come to buy meat, but they would always talk with Bob about what was going on. Kent knew that in Bob he had a caretaker much like Mack, from Mack and the Boys, as Ed Ricketts was caretaker to the people who would gather at the lab.

In every situation in social ecology you have caretakers in the informal systems that make those systems work. Another informal gathering place in Minturn was a bar called The Saloon. In the early 1970s, a particular group of men would gather, have a beer or two, and talk about the business of the town. The place was owned and run by an arthritic old character named Jeff who had been known from time to time to throw disruptive types through his front window. He was considered legendary in and around Minturn.

Across from the saloon was the old Eagle River Hotel, with Oscar Gruenfeld the proprietor. Oscar was very much like Lee Chong from Cannery Row, cautious, not to be taken advantage of. In the front of his hotel he operated a liquor store. Oscar understood that he should do everything in his power not to get involved in any process where he would have to give some of his liquor away. Every time Oscar got involved in the process with the gang across the street that gathered at the saloon, Oscar had to give up some liquor, or at least come out on the losing side.

In every situation in social ecology you have caretakers in the informal systems that make those systems work.

Ricketts talked about this as an obligation in the ecosystem, where, if you once get involved in a process, you have to be willing to go through to an ending. Kent calls that the social action of “beginnings and endings” out of Ricketts’ work. If you don’t go through the process, you never know how it would have ended, and therefore you never grow.

The theory is demonstrated in Cannery Row by showing how cautious Ed Ricketts was when someone would engage him, such as Mack, for example, in what Jim Kent calls “the Frog Economy.” Mack wanted to go on a frog hunt to gather frogs for Ricketts. In the beginning, Mack has tried to get Doc to put up money on the front end for the frogs. Then, he tried to get money for gas for Lee Chong’s old truck. Doc had thought of those ploys, so he told Mack he would call his gas-station person and arrange for Mack to get 10 gallons of gas at the station. No money was given to Mack. And when Mack got to the gas station, he tried to talk the gas station owner into first filling up half the gas tank and then giving him a buck for the other half, but the gas station man said, “No, Doc has already thought of that.” Then Mack tried to get him to put five gallons in the tank and give him a five-gallon can.” Nope, Doc has already thought of that, too.”

Finally, for humor and understanding, Steinbeck has Mack say to the station owner (by now Mack knows that Doc has thought of all the angles), “OK, but don’t forget to drain the hose into the tank!”

So the whole process of dealing with beginnings and endings is the same as dealing with the reality and being conscious of what is happening. Ricketts’ term for this was “what is.” What is right for today—not yesterday, or tomorrow, but what is right for today. That term for consultants such as Kent, is “Issues Management.” The “what is” thing was in looking at the three gathering places. In fact, Bob Gallegos’ meat counter symbolized the whole thing, as did the street in front of Doc’s Lab in Cannery Row.

About this stage of the process Kent got a lesson in non-teleological thinking. He was talking with Bob Gallegos one day at his meat counter and Bob said, “You know, we don’t want any more growth.” When you learn to deal with process rather than product you must stay in process. Had Jim been looking for a product, he would have said, “Right on.” But Jim didn’t download his values into what Bob said and go on out on the street and begin to organize an anti-growth campaign. And here is why. When Bob said, “We don’t want any more growth,” Kent was listening and reflecting as to what he was really saying. Bob was, in fact, saying that he didn’t want any of the Vail-type growth in Minturn. But they, the Hispanics, would like to participate in some growth, in something that might take place in Minturn and the Eagle Valley, because that way they could preserve their community as long as the change didn’t come in on top of them. That understanding by Kent became the underpinnings of the work in Minturn. How could the people accommodate change in a way that would preserve their culture? What they needed was to have Minturn viewed as a total ecosystem, through the eyes of a Doc Ricketts, so to speak—someone who could see the whole process as a biological phenomenon, with the ebb and flow of living and taking care of each other. So with Bob Gallegos as the chief caretaker, they formed an understanding of how they would operate in this new ecological system. What they needed were some more “descriptions” to find out what other people were thinking, and in what structure.

If you don’t go through the process, you never know how it would have ended, and therefore you never grow.

Steinbeck talked about the human part of the ecosystem. Bob Gallegos called it “productive harmony.” The basic philosophy was that the Hispanics were tied to the land and that tie made them a part of the mandates of the Forest Service, not only to preserve animals, trees, etc., but also human environments. In addition to the physical resources, the social aspects were part of the “harmony,” a new concept for the U.S. Forest Service. Kent said, “It was interesting to see harmony become part of the vocabulary of the Hispanics.” Gallegos, the meat cutter, described how the networks of the Hispanic community should proceed. They should proceed as being part of the ecology and not be managed or impacted by the changing dynamics.

These units Kent calls “informal networks.” Steinbeck called them “the phalanx.” Their primary function is to keep the society together. A function of survival—caring for each other to preserve their culture. The networks were the natural processes that moved information swiftly and accurately. As Steinbeck shows many times with Mack, that information is power.

Bob Gallegos through his meat counter put up a bulletin board so that when people came in they could see that there was an issue and that the community would have to mobilize to deal with that issue. When there were no issues the bulletin board came down. The problem, and the beauty with the caretakers and the networks, was that they were invisible to outsiders such as professional foresters, so the people of Minturn had to invite these others in to become part of the network.

If you read Cannery Row, you see beauty when people come out, when they would walk through the town. There was a routine. Steinbeck called it the “hour of the pearl”—a time between the twilight and the darkness—a time when things were different. That was the way it became in Minturn. As you define routines, you can then work within those routines. When you do that, you are working with an empowerment process because people don’t have to learn something that is different. They enhance and strengthen what they have.

What Kent was doing was mobilizing the quality of life that people bring to everyday living. Kent changed many names that Steinbeck used in the novel. “Phalanx” became “informal networks.” Places such as Flora Woods, Bear Flag Restaurant, and Doc’s lab became “natural gathering places,” called in Minturn the meat market and the saloon. Doc and Wing Chong of Cannery Row are “caretakers.”

The networks were the natural processes that moved information swiftly and accurately. As Steinbeck shows many times with Mack, that information is power.

The places were defined by the interaction of the inhabitants within their environment. Caretakers trained others to be caretakers. They learned the process of reflection and dialogue.

The Hispanics had a land ethic. They wanted to stay on their land, and that land ethic was very important to them. The one most important principle that Kent discovered was that they wanted this place to raise their families in. It was called Home.

One important story early on involved Mrs. Pena, who had her own house and another house next to her house which was an informal day care center. Essentially, the working women of Minturn dropped their children off at Mrs. Pena’s, and in the words of the formal system it was an illegal day-care operation. But to the people of Minturn, Mrs. Pena was their matriarch, their grandmother. And there was nothing that could ever happen in Mrs. Pena’s house that would ever hurt those children.

A developer sought Mrs. Pena out because her one house was in line with a ski run that could come off the back of Vail Mountain. The developer wanted that house and he wanted to tear it down so that they could put the ski lift in there and bring skiing to Minturn. On her own, Mrs. Pena’s dialogue went like this:

The developer said, “You know, for $25,000, I’d like to buy your place.”

And she said, “Well, it’s not for sale for $25,000.”

In 1971 the places in Minturn were worth around $6000, and so the developer persisted and he said, “Look, for $25,000 you can do anything you want to do in this world.”

And Mrs. Pena answered, “Well, you know, I’m doing everything that I really want to do in this world. The house is not for sale.”

Dejected, the developer walks away. Six months later, Mrs. Pena sells the house for $6,000 to a friend and neighbor who needed a home.

With this story Kent knew the land ethic was in place and he could proceed.

In many situations Kent had to put together the action as it would unfold, much as Mack did in the frog hunt, which Kent re-termed “the Frog Economy.”

Kent used the concept of the frog economy to get everyone in the networks transported from Minturn to the county seat, because the county was having a formal meeting—a critical hearing on Minturn. The county had not gone out of its way to try to involve the Minturn people. In fact, it was going to make a land-use decision that would force Minturn to capitulate to Vail Associates’ wishes. The network needed to figure out how to get these miners and their wives down to the county seat en masse during a swing shift so that they could make a statement in a manner that could be used later to educate the people on what had happened. To do that they needed mass transportation.

Henry Pacheco knew the town manager of Vail, who on occasion could use the Vail Associates’ ski buses. They were big, beautiful blue buses with “Vail Associates” and their logo painted on all their sides. They were the buses that carried people around the town of Vail for skiing, etc., and Pacheco got it in his head that those buses owned by the developers were the buses that should take these people to Eagle for the hearing. Obviously he could not go directly to Vail Associates because if he did the answer would be a firm “no.” But by going through the town manager and capitalizing on his friendship, the town manager was persuaded to ask Vail to release the buses. There wasn’t any question from Vail. They said “fine” because the town manager had asked for the buses many times before.

Now the scene switches to the county courthouse, and Kent describes a Milagro Beanfield War. Inside, the president of Vail is standing, looking out through the courthouse window along with another key person in the network who possessed technical knowledge. He was the person assigned to Vail Associates by the network to iron out what the accommodations to Minturn would be with the ski area. Six people were standing looking out the window before the meeting started—three company personnel, two planning commissioners, and Kent. On a workday afternoon when all Hispanics are supposed to be working in the mine, three blue buses pull up in front, and out of those buses come 120 Hispanics. Having been coached by their caretakers—Pacheco, Chavez, and Gallegos—the networks turned out en mass, for the first time ever, to a formal meeting. The strategy was simple: fill up the meeting room, which they did; surround the planning commission, which they did; and block the hallways in a non-threatening manner so that people just couldn’t leave the meeting.

They knew that they had only one shot. They had to keep those county commissioners and planning people there until the decision was made in their own favor. They were ready to spend the night!

The founder and president of Vail looked out the window and said loudly, “How did those people get our buses? Those are our buses!”The president, Pete Seibert, turned out to be a hero of this story. Pete Seibert had been a 10th Mountain Division ski trooper at Camp Hale during World War II and was well-liked by all from Leadville to Eagle. For the first time he began to see and understand what was happening.

In many situations Kent had to put together the action as it would unfold, much as Mack did in the frog hunt, which Kent re-termed ‘the Frog Economy.’

Pete Seibert called off the development that was happening at Meadow Mountain and Minturn. He could see the passion and knew he could not replace the significance of Minturn in the Eagle Valley. So he sat down with the caretakers—Pacheco, Chavez, Gallegos—not in the board room of Vail Associates, not in the formal offices of the county court houses, but in the informal settings of the kitchens of Minturn, Colorado. A kitchen table is a very important place for discussion in an informal environment—it levels the playing field.

Seibert said in Bob’s kitchen one night, “OK, I will not develop Meadow Mountain, but I want to develop Beaver Creek, and I need some tradeoffs.” He asked if the people of Minturn would be willing to allow Vail Associates to look at Beaver Creek as a way of preserving the community of Minturn and its culture. “You bet,” they said.

Kent explains that Pacheco became a local hero solely because he brought the Hispanic people from Minturn in the buses that belonged to the power structure. Pacheco often bragged, “Vail even paid for the gas and the drivers!”

That was very much like what Mack had done for the frog hunt. Remember, in the frog hunt Gabe goes off to get a part for his old carburetor and doesn’t come back for 160 days. One of the things that happens in the informal networks is that time is not linear—it is tribal. Kent thinks Steinbeck has taken a bad rap. People accuse him of not being loyal and of not staying in touch with people like Tom Collins, who assisted him with material for The Grapes of Wrath and so on. But what really happens in informal networks is that time is tribal. It is okay to leave and come back after 160 days. There is really no reason to stay in touch, because when you arrive back someday, you are treated as though nothing has really happened. Again, here is profound proof from Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. If you allow time to be linear, then you judge people and you force them to lose their energy and you diminish their ability to interact with you, because once you judge them over a time-situation you have excluded them. If you read carefully in Cannery Row, time was a tribal concept, a very valuable concept to pick up on when rereading the novel.

One of the things that happens in the informal networks is that time is not linear—it is tribal.

By 1977 in Minturn, the caretakers had been technically trained and could anticipate the dynamics of economics that would adversely impact their culture.

The New Jersey Zinc Mine that had been operating on top of Battle Mountain and polluting the upper Eagle Valley for over 50 years was the major employer of the Hispanics who lived in Minturn. The absentee mine owners every year would threaten to close the mine as the workers voiced a need for a higher wage. To divert a miners’ strike, the mine owners each year would announce that the mine was going to remain open. The Hispanic miners would then back off from their demands and continue to work at the same wage under the same conditions.

Bob Gallegos went to Jim Kent one day and said, “One of these years they are going to close that mine.”

What needed to be done was to have the miners learn to believe that one day the mine might close and then to actually prepare for that eventuality.

Bob Gallegos was now managing Kent’s “Life Options for the Future” project in Minturn. The mission was to get the miners to understand that the mine was in fact going to close. Had the caretakers proposed themselves as experts and called a meeting and said, “Listen, you guys, the mine is going to close. What are we going to do?,” the workers would have closed their minds and continued to do as they had for years; they would have continued to work so that they could feed their families. A classic example of the need for self-discovery in a natural ecosystem: Gallegos and the other caretakers decided to work with the natural leaders—those miners who were respected by the other miners.

There were about 12 of them. They met in Bob’s kitchen on a Sunday. The caretakers talked of things in Spanish and they talked of things in English. They did a lot of things with flip charts and they asked these miners to project what the owners would do first if that mine was going to close. They listened, and then wrote down a list of several things that they felt would probably happen.

They listed things like: the owners will stop ordering expensive wood pillars, or they will start mining out the dirt pillars where they know there is high grade ore, or they will repair worn out tools rather than buy new ones. They came up with a list of 10 items.

What the caretakers and organizers wanted were those 10 items burned on to the flip charts in the languages that the miners could see and read for themselves.

A week later, they took those 10 items and put them onto a checklist and said, “Tomorrow when you go into the mine, take the list and mark any item that you said would be happening if the mine were going to close, but only mark it if it is already happening.” The miners came back the next Sunday, and to a person they had marked nine or 10 of the items.

They owned it! They owned the discovery that the mine was going to close! The next step was to network this information in the mine, sharing the discovery with everyone.

They didn’t know when the mine was going to close, they just knew it was going to close. The message was the same concept as in Cannery Row—when Doc would carry the message, people would believe it.

The informal network then planned what could be done when the owners announced the closure. They had to diversify the community in a true ecological fashion. The two foundations of sound ecology are persistence and diversity.

The good people of Minturn listened as Pacheco, a caretaker, told the men over at the saloon, “For Hispanics in a small town in Colorado there is no place to go!”

“Where do we go? East Los Angeles or the barrios of north Denver? We have to make it here!”

“Is” thinking, as Ricketts explored in The Outer Shores, was to be found not in searching for causes, but rather for ways of breaking through.

A classic example of the need for self-discovery in a natural ecosystem: Gallegos and the other caretakers decided to work with the natural leaders—those miners who were respected by the other miners.

What they did in Minturn was to float ideas. The same idea as Cannery Row with Ricketts’ and Steinbeck’s “It might be so.” Ideas were put into the networks, just as the miners would be put into the mine to discover why it might indeed be closed.

Then the people would use their intuition, their instincts, and their values. That would deter them from their personal system. They had to learn how to absorb and accommodate outsiders without the outsider feeling rejected or confronted because of a different culture. It was quite like Mack on the frog Hunt in his handling of the farmer. Mack was able to literally bring the farmer into their network, and he became a part of Mack’s own agenda.

When the people of Minturn needed to bring an outsider in, they did so without being threatened. They became a part of the bigger picture until they felt they wanted to exit or there was an ending. The people became very conscious of Beginnings and Endings. The people became very conscious of Breakthroughs. The people could look at and see what was going on in another environment and make internal adjustments so that they could benefit from what was going on and sustain their own culture.

When Mack got back with the frogs, he finally found his leverage point to open up the “Frog Economy.” The frogs were worth a nickel to Doc, and if they were worth a nickel to Doc, then they must be worth a nickel to Lee Chong. But Doc, the caretaker, was not there when Mack and the boys got back. The point of this, according to Kent, is that things can get out of hand if a key caretaker isn’t there when you come to an ending. So instead of Lee Chong saying, “No, Mack, you have to wait until Doc gets back,” Lee makes the mistake of agreeing with Mack by saying, “Yes, the frogs are worth money.” So Lee Chong sets up a system where Mack and the boys can buy food and booze with frogs. . . .

Caretakers and Endings on Cannery Row and in Minturn

They were very conscious in Minturn, when they were coming to an end, to make sure that the key actors or caretakers were in on the ending. Otherwise it would have gotten sloppy. In Cannery Row, Doc gets mad and even hits Mack. In reality, those moments are too disruptive and can bring an entire movement down. You must complete the ecological loop because that produces harmony—productive harmony.

It was interesting to me that Kent converted Steinbeck’s social action theories concentrated in Cannery Row through the fictional mode of a novel into reality. It was even more incredible that he learned an ecological construct that included culture and real people based on a fictional Ed Ricketts. It was utterly amazing how readily adaptable Ricketts’ holistic philosophy could be to reality.

I asked Jim Kent about that and he said, “Well, today it is known as Issue Management, a term that I coined, along with the Discovery Process, but even that was based on Steinbeck, who referred to it as discipline through observation. The key, in Minturn, was to have the people become describers, because that freed them from the assumptions in their culture. It gave them some self-confidence in directing their own lives.”

I commented that there was a culture assumption in Monterey, California, up until 1948, an assumption that macho young Italians and Sicilians should be fishermen, as their fathers and grandfathers had been before them.

They were very conscious in Minturn, when they were coming to an end, to make sure that the key actors or caretakers were in on the ending.

Jim commented:

“Exactly. But at this juncture is where the parallel of Steinbeck’s social action thing expressed in Cannery Row was different from Minturn, because Steinbeck was writing fiction. He chose to limit his description to one short street called Cannery Row. What we did in Minturn was through the Discovery Process and by expanding networks. We had them think and reflect about their children, about how they could consider a preferred future and yet still retain their culture.

“They discovered the need for careers and discovered what they needed to do now to assure that their children had careers. They had to diversify the families. They encouraged the senior members of the family to continue working in the mine. By this time, they knew the mine was going to close. The other members of the family would quit their $18 an hour jobs for $4 an hour jobs.

“The people discovered how they could use the development of Beaver Creek to produce careers, how they could work with the Forest Service to produce careers.

“The people worked with Vail Associates and Pete Seibert. All of these possibilities were in the Forest Service permit to develop ski courses. They proposed a career development program, not just a promise of a $5 an hour job. They worked with banks, starting by having them hire young people as tellers. They worked with schools on reading and on survival levels of mathematics. And they worked on cultural values. They worked with community colleges with a program called a Career Conversion Program. They had another program called Life Cycle Mitigations where they negotiated with the big hotels that would be built at Beaver Creek. Ancillary to all of this, many Hispanics in the town wanted to set up their own business.”

The mine closed December 16, 1977, nine days before Christmas, but the people of Minturn were poised for new things outside the confines of their own cultural habitat. The difference of the reality of Minturn to Steinbeck’s Cannery Row was that they were able to broaden their culture base as an expansion of the ecological borders.

I reminded Jim of my friend Kenneth Boulding, the great scientist and economist from Boulder, who talked about entropy of everything unless it develops the ability to change.

You need description and ownership. Mack and the Boys in the context of the social Discovery Process were geniuses. They knew how to reflect on the ecological system. Ed Ricketts, or “Doc,” through Steinbeck, was the ideal counselor. He was always in the background, but he knew how to close the ecological loops.

The difference of the reality of Minturn to Steinbeck’s Cannery Row was that they were able to broaden their culture base as an expansion of the ecological borders.

Steinbeck developed a social action theory and described it through his fiction. He used his friend Ed Ricketts’ holistic philosophy and Ed Ricketts’ ecological understandings and converted them into a novel the essence of which revolved around the informal structure. It remains a piece of brilliant fiction.

Jim summed it up by saying, “When you look deeply at Steinbeck’s writing in Cannery Row and understand the real Ed Ricketts, you find a whole preventive theory. I hope others will discover that the thing started with Ed Ricketts, but that it was told by the Nobel Prize-winning storyteller John Steinbeck.”

After talking with Kent and seeing exactly how deeply Cannery Row had affected his life, I found myself deep in thought.

There are only two roads you can take to go from Carbondale, Colorado to Denver. One is Highway 82 through Aspen and then over Independence Pass, which is 12,000 feet high and closes from November to June. The other is Interstate I-70 through the Glenwood Canyon by the Colorado River and then up the Eagle Valley past Beaver Creek and Vail toward the Continental Divide, on toward Denver and the level plains stretching eastward to the Appalachians.

As you pass Avon and the huge ski area, Beaver Creek, and before you reach Vail, there is Highway 24, cutting off on your right with a sign that reads “Minturn—5 miles, Leadville—24 miles.” That was the route Jane and I took every week for three years on our way to a cancer clinic. We most often stopped at The Saloon in Minturn, where we talked to a third-generation Hispanic caretaker named Martinez.

“How’s it goin’?” we would ask.

“Did you see the new restaurant across the street run by Lopez called Vail’s Derriere, which means ‘Vail’s ass’? Just over the top of the hill behind this street is Vail, where all the rich tourists hang out.”

“What about the other businesses?” we asked.

Steinbeck developed a social action theory and described it through his fiction.

“Well, there are 35 businesses now in Minturn, all run by Hispanics. Joe Marcus owns the Exxon station over on I-70, and Bob Gallegos and his brother have the biggest masonry business in western Colorado. There isn’t a rock wall or stone house in Beaver Creek or Vail they haven’t built, including President Ford’s house, and Dan Quayle’s, and Ross Perot’s.”

“What happens to the young people that graduate from high school?”

“Most of them go to Colorado Mountain College for training in hotel management. There are plenty of jobs. Many of the managers are from Minturn. They can work there and live at home. Renting is very expensive here in Minturn and you can’t buy a house because there aren’t any houses in Minturn for sale.

When Jane and I would leave Minturn and head up Battle Mountain, we usually pulled over and stopped to look at Notch Mountain in front of the 14,000-ft. Mount of the Holy Cross. From there you can see the company town of the New Jersey Zinc Company. It has to be the largest ghost town in the world. The EPA in the 1980s constructed a chain link fence around the mine and the abandoned houses and declared it a Super Fund site. The mine leaks lead and zinc poisons into the fractured rock system that drops into the Eagle River that flows through Minturn on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. My uncle used to say: “The fishing ain’t very good.”

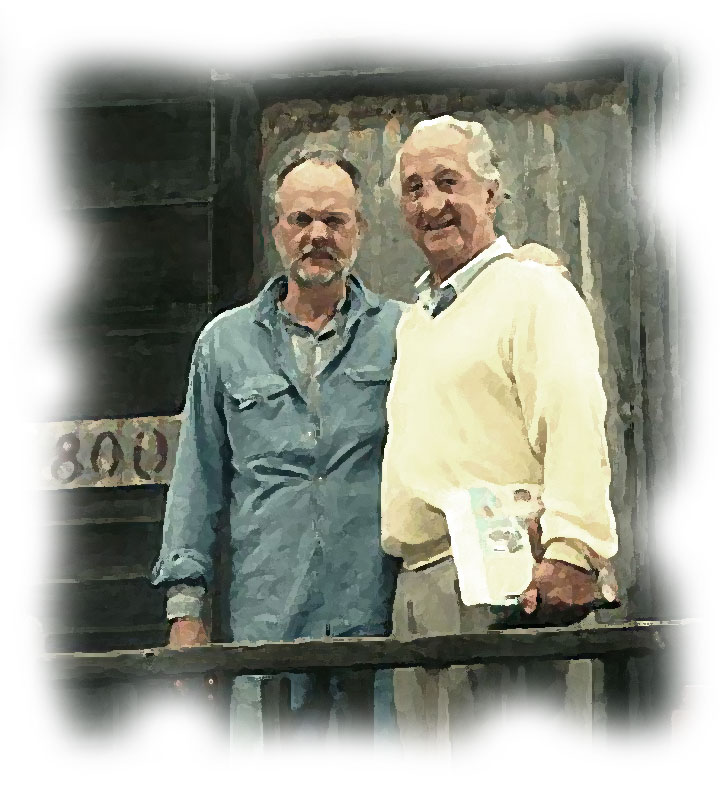

Copyright © 2006 James Kent Associates (JKA). All rights reserved. Image of Mack and the Boys courtesy Pat Hathaway Historical Photo Collection. Image of James Kent and Ed Larsh courtesy James Kent.

I discovered Jim Kent’s brilliance on a visit to Cannery Row.

Needless to say I admire my friend Jim Kent very much and appreciate him in my life. I just wanted to emphasize how much improved and expedited his discovery process would be and how the resulting social ecology plans would be if, for instance, the consultant understood the individual as Steinbeck did, that is from a Jungian point of view. They would know, for instance that in informal networks, particular types gravitate to particular roles. And this means something to producing or selling ideas to that role player. Without this concept in mind the consulting team must begin considering the individual with a clean slate, a much more tedious, time and resource consuming perspective.

In a letter written 9/27/44 to his friend Carlton Sheffield, Steinbeck wrote:”I don’t know whether it [Cannery Row] is effective or not. It s written on four levels and people can take what they can receive out of it. One thing-it never mentions the war-not once.”

The great thing I learned from Jim Kent, via John Steinbeck, is that informal networks get things done. They are the means by which survival happens at the grassroots, as shown so well with Mack and the Boys. Talking over stuff in your gathering place, with trusted friends, to figure out the changes going on and what your next steps will be–that is the essence of community life. To be part of that system–to become known and accepted within circles like that–and change begins to happen from the inside out. Change that people own, change that is impenetrable because it is culturally-based.

In our work, we have identified eight network “archetypes”–recurring jobs that can be observed in networks to promote their functioning. The eight are: caretakers, communicators, gatekeepers, bridgers, historians, storytellers, opportunists and authenticators. Understanding the archetypes is a way to work seamlessly within informal networks to explore change, reflect on options, and develop strategies for action.

These are not arcane musings, but directly relevant to the health of society in the 21st century, as the pace of social change accelerates and the blending of populations world-wide accelerates. As corporations and governments grapple with understanding the direction of change and to work with the social diversity present in any locale, Steinbeck’s insights are ever more relevant. And the message is clear: Learn community first, before introducing a new project, program or policy.

These social trends are why Jim Kent and I in 2002 formed the Center for Social Ecology and Public Policy, believing that public policy ought to be derived from understanding cultural life in a community–the practices, beliefs and stories by which people try to sustain their lives. When we work in areas such as improving the implementation of the new health care law, figuring out how to do a new electrical transmission line, or developing collaborative approaches to forest management, Steinbeck, Mack, and Doc Ricketts are there to coach us on the humanity of our endeavors as the driver of change.

Kevin Preister, CSEPP, June 30, 2014

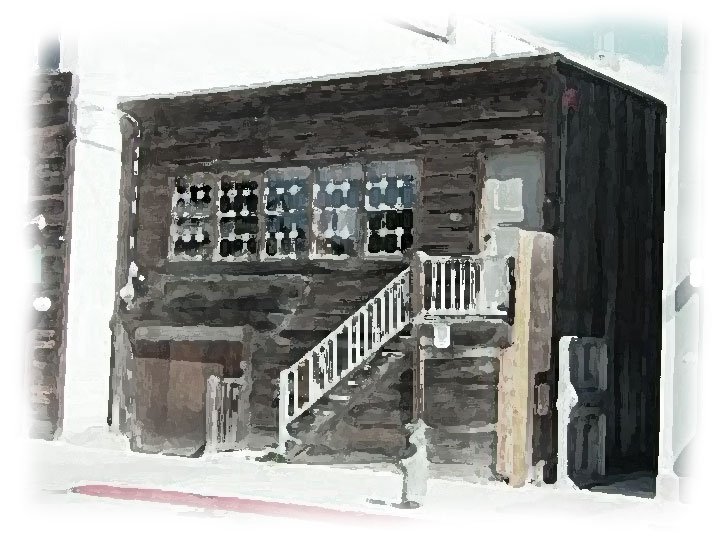

this is a blatant ad: the city of Monterey offers free tours of Ed Ricketts’ lab. Check the website for the city of Monterey. tours are about one hour long; conducted by a knowledgeable docent. you will here recordings from interviews by people who knew Ed Ricketts – Carol Steinbeck, Joseph Campbell, Bruce Ariss, etal. Next tour in July.

Thank you, Herb. Please share the time, date, and other requirements to participate in the July tour with readers who are interested in taking part.

Thank you Herb. For those who have not been in the lab it is a stirring experience. The physical space is exceptional in the sense of the flow and the spirit of Ed Ricketts, Steinbeck and others whose presence you can still feel. It is a must for anyone that desires to sense the time and place of the gatherings, the reflections, the Gregorian Chants, the writing, the plotting–the life that took place here. We wrote the book: Doc’s Lab: The Myths and Legends of Cannery Row at the Lab. In those days it was still owned by the second lab group that included Ed Larsh, and Eldon Dedini. The second lab group picture is on the wall by the bar. What a group they were. As each iincndividual passed away it was noted in the picture. Don’t miss it when you visit the Lab. In keeping with the creativity of this space from Steinbeck’s time this second group who would go there to listen to Ed Ricketts music on his old record player (still there) incubated the Monterey Jazz Festival out of this space..

The second lab group turned the Lab over to the City of Monterey in order to preserve it for posterity. The City has done an outstanding job of honoring the integrity of the Lab. When you take your tour just relax and feel the presence of the the ordinary folks who once inhabited Cannery Row and hung out at Doc’s Lab. Some of the ordinary became famous to the larger world, some were famous to Cannery Row–but all were famous in one way or another as they created life in this exceptional place called Doc’s Lab.

I have known and learned from Jim Kent since 1988. I have worked as a Town Manager in several Colorado communities for the last 30 years and in every one of those communities I have worked with Jim and used his theory and practice of issue management and informal networks. While each of the communities I worked in Aspen, Basalt, Carbondale and New Castle have benefited from Jim’s work, an even more powerful impact was registered on me as a member of these communities. My life’s work in local government is very fulfilling and I can remember the day that it started to become real for me.

In the mid-90’s, I was in Monterey with Jim Kent, Carolyn Hunka and Ed Larsch celebrating Ed’s book “Doc’s Lab: Myths and Legends of Cannery Row” in which Jim’s chapter talked about Minturn. One afternoon Jim and Ed invited me to come to Doc’s Lab to participate in a celebration with a smaller group. Many of those at the Lab that day had a connection to the First or Second Lab Groups and they told stories. The stories were interesting and fun and I felt honored to hang on the periphery of this group, I began to understand the power of community, informal networks, gathering places and caretakers. But perhaps most important I began to understand the power of listening to the stories of community members as a way of understanding that community and its beliefs and dreams. Until that day Jim’s concepts were somewhat abstract, but after that day I began to apply Jim’s idea in a way that was real for me and real for the community. I’m still learning from Jim and every time I talk to him he takes me a little deeper into his theory.

Jim’s work is so important and today it’s application is even more vital as many small communities find their resource base stagnant or shrinking. By using Jim’s theory communities can tap into their own intelligent and knowledge to solve problems and create plans without the expense of outside consultants. Also, using Jim’s theory give communities ownership and control of their future, which is why many of us live in small communities.