John Steinbeck’s dog Charles le Chien remains a creature to be envied, having been squired across mid-20th century America by his restless owner, the author who transformed their journey together into Travels with Charley, a lyrical paean rich in social commentary that became a favorite of Steinbeck readers then and now.

As if a 10,000-mile, tree-filled experience weren’t heavenly enough reward, Elaine and John Steinbeck’s big blue Poodle also gained literary immortality, taking a star-turn in the book that records a road trip taken more than 50 years ago and continues to be read and debated. The appellation lucky dog comes to mind, but Charley was ready for his role as the author’s celebrated sidekick. Steinbeck wanted to see America on his own, but needed a companion who listened well. Charley did.

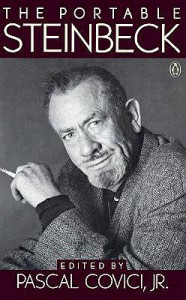

Wartime Portable Steinbeck Published BC (Before Charley)

No fan of John Steinbeck will ever be quite as lucky as Charley-dog. But may I suggest a second-best experience for two-legged vacationers half a century after Travels with Charley became a national bestseller? Take along your own copy of Viking’s The Portable Steinbeck when you travel this summer. Like John Steinbeck’s polite, attentive Poodle, this popular anthology of the author’s work travels well and fits any space.

No fan of John Steinbeck will ever be quite as lucky as Charley-dog. But may I suggest a second-best experience for two-legged vacationers half a century after Travels with Charley became a national bestseller? Take along your own copy of Viking’s The Portable Steinbeck when you travel this summer. Like John Steinbeck’s polite, attentive Poodle, this popular anthology of the author’s work travels well and fits any space.

A compact book designed for stuffing into suitcases and knapsacks, The Portable John Steinbeck remains an unsurpassed introduction for newcomers to John Steinbeck’s writing and a continuing delight for long-time lovers of The Red Pony, East of Eden, and The Grapes of Wrath. With apologies to a fellow author Steinbeck admired deeply, allow me to call The Portable Steinbeck a moveable feast for readers on the run who favor timeless prose and strong ideas over mindless literary escapism.

The Portable Steinbeck was first published in 1943 at the height of World War II as part of the Viking Portable Series—a literary brainstorm attributed to the writer-broadcaster and soldiers’ champion Alexander Woollcott. As noted at the website AbeBooks.com, “The physical characteristics of the wartime Portables owed more to practicality than anything else. The books were meant to be ‘built like a Jeep: compact, efficient, and marvelously versatile.’”

Idea by Alexander Woollcott, Introduction by Pascal Covici

Woollcott wanted the Portables produced for “the convenience of men who are mostly on the move and must travel light”—soldiers far from home fighting in both theaters of an uncertain war. John Steinbeck shared Woollcott’s belief in the democracy of books and the heroism of young soldiers, some as young as 17. The editors at Viking echoed Woollcott’s words on the jacket of the original Portable Steinbeck, the second book they published in the series.

The Portables, they explained, were produced to present “a considerable quantity of widely popular reading in a volume so small that it can conveniently be carried and read in places where a book of ordinary format would be a hindrance.” Domestic resources were scarce, and the wartime Portables featured “light paper, small margins, and other production economies” while offering a “well and legibly printed and sturdily bound” book designed as much for durability as for literary quality and content.

Like Travels with Charley, Portable Steinbeck Still Popular

Sturdy indeed. The John Steinbeck anthology has gone through numerous editions since 1943, although this Baby Boomer patriot particularly cherishes a pair of copies published in the 1980s, each with an elegant introduction by Pascal Covici Jr., the literary son of Steinbeck’s loyal editor and friend from the prewar 1930s.

The younger Covici’s introduction to John Steinbeck’s long-lived anthology is a model of to-the-point prose:

The gusto of Homer and of Whitman is indeed here, along with the thoughtfulness of Emerson, that philosophical presence which more and more readers have been finding woven into the sturdiest standards of American literature. A humor sometimes sly and often carelessly robust finds its way onto Steinbeck’s pages too.

Contemporary cynics might anticipate a lawyerly disclaimer at this point: Individual reader’s results may vary. But the book’s content lives up to its billing as an introduction to the variety of works written by John Steinbeck, including in its pages the complete version of The Red Pony and a self-contained segment from Cannery Row, along with excerpts from The Grapes of Wrath and (in later editions) the full text of John Steinbeck’s inspired Nobel Prize acceptance speech.

Portable Steinbeck—Beach Reading for the Eternal Ocean

I can think of no better way to make the inner light shine brighter for modern readers than this brilliant passage from The Grapes of Wrath:

If you who own the things people must have could understand this, you might preserve yourself. If you could separate causes from results, if you could know that Paine, Marx, Jefferson, Lenin, were results, not causes, you might survive. But that you cannot know. For the quality of owning freezes you forever into “I,” and cuts you off forever from the “We.”

Or read the sunny lines spoken in passionate hope for the future by John Steinbeck in Stockholm in 1962:

And this I believe: That the free exploring mind of the indivdiual human is the most valuable thing in the world. And this I would fight for: the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any idea, religion or government which limits or destroys the individual. This is I what I am and what I am about. I can understand why a system built on a pattern must try to destroy the free mind, for that is one thing which can by inspection destroy such a system. Surely I can understand this, and I hate it and I will fight against it to preserve the one thing that separates us from the uncreative beasts. If the glory can be killed, we are lost.

The Portable Steinbeck is a summer book for any season, but it’s far from shallow—a beach read, if you will, that plumbs that ocean of eternal wisdom. Covici in his introduction describes the progression and profundity of the excerpts selected: “a focus of interest more implicit than realized in the very early works, then gradually emerging into sharpened consciousness until it becomes a matter of articulated intention.”

As a child of icy winters spent on the Great Lakes, I embrace summer days. Like John Steinbeck with Charley, I relish them with my favorite fellow-traveler, The Portable Steinbeck, in tow.