Years ago I lived in a house on California’s Monterey Peninsula where John Steinbeck had been a frequent visitor. Recently, while reading Jackson Benson’s Looking For Steinbeck’s Ghost—the story behind Benson’s biography of Steinbeck—I was reminded of Thomas Mann’s remark that Mann enjoyed reading reviews of his own books. “From them I learn what it is I’ve written,” he said. Similarly, reading about John Steinbeck reminds me of what I’ve already read by and about the author, and what I heard from those who knew him in Pacific Grove and Monterey, where I moved after Steinbeck had left for New York.

I was reminded of Thomas Mann’s remark that Mann enjoyed reading reviews of his books: ‘From them I learn what it is I’ve written.’

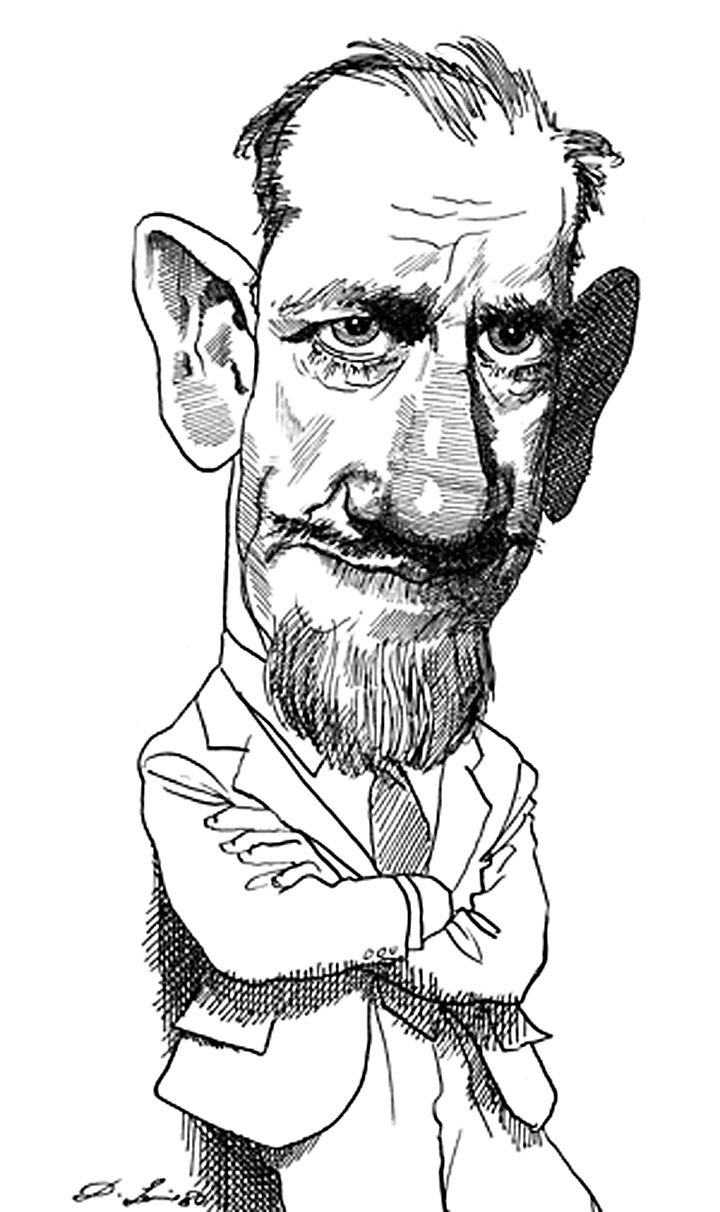

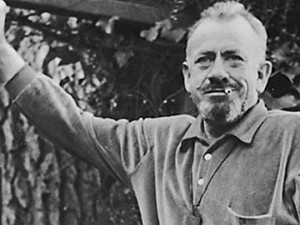

According to the artist Judith Deim—the former owner of my house in Monterey—she and her former husband, the artist Ellwood Graham, had painted John Steinbeck’s portrait in their kitchen. Steinbeck, she said, sat on a platform constructed by Graham, scribbling away on a new book while each artist painted the personality they saw in their famous friend. Although some people in Pacific Grove doubt Deim’s story, I didn’t and don’t.

One reason I believed her is that she also told me about an incident involving John Steinbeck that took place during a trip she and Graham made to New York several years later.

Low on funds, they called Steinbeck to ask if he would vouch for a check they needed to write on their account at a bank back in Pacific Grove or Monterey. Steinbeck, she said, bluntly refused. From her point of view, that ended the friendship for good.

From this story, it seemed that Steinbeck had become a snob. But the writer had once observed to me that everyone’s recollections are unreliable because no one has a perfect memory. People naturally exaggerate and embellish—adding and subtracting to make a complicated story simple or a simple incident seem more interesting than it really was. Judith Deim’s story about Steinbeck’s supposed snobbery came to mind recently when I received a note from a friend still living on the Monterey Peninsula. It proves Steinbeck’s point about not trusting memory.

Judith Deim’s story about Steinbeck’s supposed snobbery came to mind recently when I received a note from a friend still living on the Monterey Peninsula. It proves Steinbeck’s point about not trusting memory.

A longtime resident of Pebble Beach and the Carmel Highlands, my friend was responding to my request for information about Steinbeck. Had he known the writer, and if so, did he have any stories to share? His answer was brutally honest. No, he replied, my Steinbeck lore coincided with my periods of heavy alcohol use, so I can’t really know how much of it is sound history and how much is fabulous fabrication. Other than being at the same place at the same time, I have no secure memory of him. I’ve made up some tales that I told for years as fact, but know much of it never happened or happened to someone else. I’d rather not attempt to winnow the few solid grains from fable’s harvest.

A longtime resident of Pebble Beach and the Carmel Highlands, my friend was responding to my request for information about Steinbeck. Had he known the writer, and if so, did he have any stories to share?

Back to Benson’s book. Reading it reminded me how private John Steinbeck was, and how deeply he cared that he be defined by what he wrote, not what others said about him. Was Steinbeck’s reticence a sign of aloofness, as Deim’s story about the check suggests, or was there more to the author’s attitude than insecurity or shyness? An incident shared by another couple I knew on the Monterey Peninsula—Matt and Vivian—corrected this impression.

Back to Benson’s book. Reading it reminded me how private John Steinbeck was, and how deeply he cared that he be defined by what he wrote, not what others said about him. Was Steinbeck’s reticence a sign of aloofness, as Deim’s story about the check suggests, or was there more to the author’s attitude than insecurity or shyness? An incident shared by another couple I knew on the Monterey Peninsula—Matt and Vivian—corrected this impression.

Was Steinbeck’s reticence a sign of aloofness, as Deim’s story about the check suggests, or was there more to the author’s attitude than insecurity or shyness?

In the 1950s Matt and Vivian worked as on-call caterers for parties, including grand soirées at big homes in Pebble Beach, near Carmel-by-the Sea. One night they were visiting me at my house on Huckleberry Hill—the one where Barbara Stevenson (her real name, before she became Judith Deim) said she and Ellwood Graham had painted Steinbeck years earlier.

Seeing a copy of The Wayward Bus on my writing desk, Vivian stated, “We saw John Steinbeck once. It was at a very, very posh party in Pebble Beach.”

I’m not sure she used the word posh. It’s more likely she said the event was classy.

Her husband came over. “Yeah, he was a pretty snobbish guy, that one, sitting in a corner by himself all the time,” Matt explained. “He was dressed in a cape that had a red lining, and he never got up. He let everyone at the party come to him. I thought he was being pretty damn standoffish, sort of saying, ‘I’m famous, you people come over here if you want to talk to me.'”

“‘He was dressed in a cape that had a red lining, and he never got up. He let everyone at the party come to him. . . . ‘

“Everyone did, too,” Vivian said. “Matt was going around the room serving drinks, and we both saw how people had to go over to shake his hand or talk to him. That’s Steinbeck, people kept saying.”

“That’s how it went until the party was breaking up,” Matt continued. “And then Steinbeck stood up and said, ‘Well, I’ve seen life on your side of the hill. Who’s in favor of having a look at life on my side of the hill?’ Several people said yes, and then he came over to us. ‘How’d you like to come along?’ he asked Vivian and me. I said sure, we’d like that, and after we’d finished everything we had to do at the house in Pebble Beach, we followed the last guests out the gate and headed north to Pacific Grove.”

And then Steinbeck stood up and said, ‘Well, I’ve seen life on your side of the hill. Who’s in favor of having a look at life on my side of the hill?’

“So there we were, in the front room, waiting for John. He’d gone off for a minute,” added Vivian.

“Yeah, and he came back carrying a gallon jug of red wine,” said Matt, finishing the story. “He’d taken off that cape and said, ‘I’ll show you how to take an honest drink,’ and he put his finger in the handle of the jug and lifted it onto his shoulder and took a long swig. Then he passed the jug around.”

“‘He’d taken off that cape and said, ‘I’ll show you how to take an honest drink’ . . . .

Everyone embellishes. But Matt and I worked side by side, naked to the waist, swinging mattock and pickaxe for a year helping to landscape the huge Morse property in Pebble Beach. He and Vivian were a hard-working, middle-aged black couple who knew Steinbeck by reputation without ever having read his books. Unlike the friend who sent me the note, they had no reason to fabricate a story. Witnessing John Steinbeck’s transformation from the guest in the cape at Pebble Beach to the host hoisting a jug of red wine on his shoulder in Pacific Grove convinced them that John Steinbeck was relaxed, down-to-earth, and far from a snob.

Everyone embellishes. But Matt and I worked side by side, naked to the waist, swinging mattock and pickaxe for a year helping to landscape the huge Morse property in Pebble Beach. He and Vivian were a hard-working, middle-aged black couple who knew Steinbeck by reputation without ever having read his books. Unlike the friend who sent me the note, they had no reason to fabricate a story. Witnessing John Steinbeck’s transformation from the guest in the cape at Pebble Beach to the host hoisting a jug of red wine on his shoulder in Pacific Grove convinced them that John Steinbeck was relaxed, down-to-earth, and far from a snob.