The publication of John Steinbeck’s “With Your Wings” continues to stimulate conversation about the writer’s understanding of African-Americans and the roots and relevance of his forgotten World War II short story about a black Air Force aviator. Last week Steinbeck scholar Robert DeMott challenged assumptions about the story’s origins. This week Susan Shillinglaw, author of On Reading The Grapes of Wrath and Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage, interprets the story’s African-American hero in the context of Steinbeck’s World War II experience and writings about African-American characters and issues. Like Robert DeMott, she responded generously to my request for expert comment about “With Your Wings.”

Susan Shillinglaw interprets the story’s African-American character in the context of Steinbeck’s World War II experience and writings about African-American characters and issues.

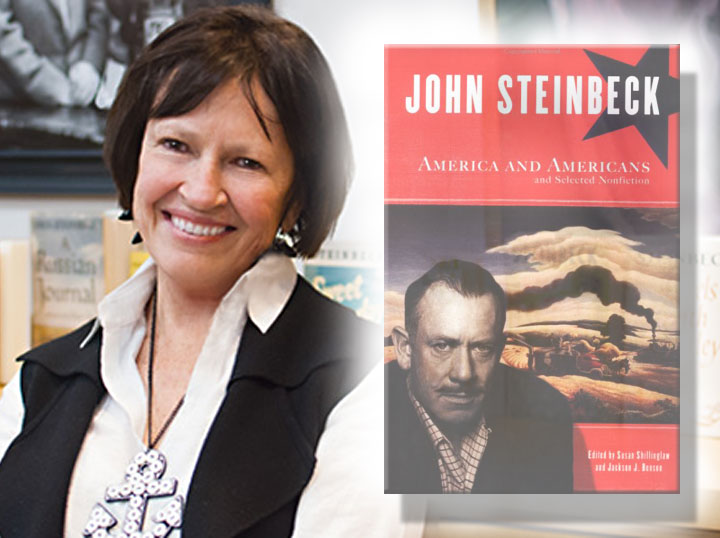

A professor of English at San Jose State University, she teaches the only regularly scheduled college-level John Steinbeck course offered anywhere. As Robert DeMott’s successor as director of SJSU’s Center for Steinbeck Studies, she introduced previously unpublished Steinbeck works of various kinds in Steinbeck Newsletter and Steinbeck Studies. These included the short story “The Kitten and the Curtain,” “The God in the Pipes”—an early fragment of what became Cannery Row—and an omitted chapter from the novel, “The Day the Wolves Ate the Vice Principal.” She wrote introductions for popular Penguin Classics editions of Steinbeck’s fiction, co-edited John Steinbeck’s America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction, and is co-editing a major Steinbeck reference work. Her 25-year record of teaching, editing, and writing was recognized by her designation as SJSU’s President’s Scholar in 2012-13. She is also Scholar in Residence at the National Steinbeck Center and co-director of a summer program on John Steinbeck for high school teachers funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

On Reading “With Your Wings”: African-Americans in John Steinbeck’s Life and Writing in and out of World War II

Susan Shillinglaw’s enlightening comments on the cultural and historical context of John Steinbeck’s World War II character William Thatcher, the African-American hero of the newly published short story “With Your Wings,” are quoted in full:

“This aviator, a second lieutenant with gold bars on his sleeves, would have earned his flight wings in Tuskegee, Alabama, where all African-American pilots were trained during World War II. ‘To have gone through the schools they must be very good, very intelligent and alert,’ Steinbeck writes in Bombs Away, a book-length propaganda piece published in 1942 on assignment for the U.S. war department in which Steinbeck lucidly explains the training of bomber pilots.

‘This aviator, a second lieutenant with gold bars on his sleeves, would have earned his flight wings in Tuskegee, Alabama.’

“Presumably Steinbeck produced ‘With Your Wings’ after writing Bombs Away and following his stint as a war correspondent covering England, North Africa, and a daring diversionary maneuver by Allied forces off the coast of Sicily and southern Italy. It’s tempting to think he wrote his short story after he returned from the front, where he might have encountered the Tuskegee Airmen, the 99th Squadron of the Army Air Forces first posted to North Africa in April 1943—four months before Steinbeck arrived at a ‘North African post,’ as in notes in Once There was a War, a collection of his World War II dispatches. Both Steinbeck and the 99th squadron then went on to Sicily, so it’s quite possible he knew and admired men like William Thatcher in this first African-American squadron posted overseas in World War II.

‘It’s tempting to think Steinbeck wrote his short story after he returned from the front, where he might have encountered the Tuskegee Airmen.’

“This aviator wants to detach from his 16-man group, to go home to ‘get something,’ to think about himself only. ‘He had thought to come home in triumph,’ a hero, a man set apart. But instead, like Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, he discovers he is a group man, buttressed by family and community and ‘every black man in the world.’ That’s ‘something’ to hang on to.

‘Like Tom Joad, William Thatcher discovers he is a group man, buttressed by family and community and “every black man in the world.”‘

“Steinbeck’s lean little sketch, which reminds me a little of his short story ‘Breakfast,’ relies on sharp details: the aviator’s gold bars, straightness (the men ‘rigid as cypress logs,’ the aviator behind the wheel of his car, the young cotton, the standing community), the sun. It’s such an ordinary scene—except that the man is black, an exemplar because he’s earned those wings.

‘Steinbeck’s lean little sketch relies on sharp details: the aviator’s gold bars, straightness, the sun.’

“Steinbeck created a dignified African-American—Crooks—in his earlier novel Of Mice and Men, made into a movie in 1939. A dignified black man also occupies the lifeboat in another Steinbeck novella—Lifeboat—made into a movie in 1944. In the 1960s Steinbeck wrote about race in a long essay, in a letter to Martin Luther King, Jr., in Travels With Charley in Search of America, and in his 1966 volume of essays, America and Americans.

‘Steinbeck created a dignified African-American—Crooks—in his earlier novel Of Mice and Men. A dignified black man also occupies the lifeboat in another Steinbeck novella made into a movie.’

“Throughout his career John Steinbeck was deeply concerned with the common good, a phrase I recently heard NEH Director William Adams discussing on the Diane Rehm radio show. Steinbeck’s sense of the common good, I think, had something to do with empathy, humility, and understanding—for all.”

It doesn’t appear that there’s a bottom to what we don’t know about John Steinbeck and his amazing dedication to the message Susan cites from the NEH’s Bill Adams: “the common good” — a political and humanitarian principle being lost in America.

This is really enlightening and stimulates so many more interesting questions about Steinbeck’s attitudes toward African-Americans. I might just add that in Spring 2007 Steinbeck Review published an interview with Corinne Cook about her experiences with Steinbeck in 1949, when Steinbeck arranged for the flight training of James Neale, an African American he had employed, and whom he asked to fly across the country to retrieve his sons from New York. “Neale was trained two times a week for six weeks in one of the Cessnas,” Cook recalled (see pp. 95-101), And she remembers vividly Steinbeck’s readiness to counter the racism with which his request to train a black man to fly was at first greeted.