Fresh questions raised by scholars about the source of John Steinbeck’s brief short story “With Your Wings,” recently published for the first time, reminded me that Steinbeck’s college friend, the writer A. Grove Day, once sent me a personal letter with an eye-witness explanation of the incident behind “The Snake,” an earlier short story set in Doc’s Lab on Cannery Row. “The Snake” was written before Tortilla Flat appeared in 1935, and Steinbeck’s friend Bruce Ariss, the Cannery Row painter-writer-publisher, printed it as “A Snake of One’s Own” (the original title) in a local publication called The Beacon. In 1938 the short story was published in Esquire magazine and in Steinbeck’s classic short story collection The Long Valley, where it continues to attract readers fascinated by its gritty, gruesome subject and intriguing origin.

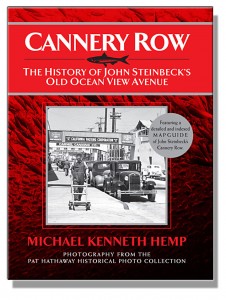

“The Snake” takes place in a familiar version of Ed Ricketts’ Doc’s Lab on Cannery Row, a frequent venue in Steinbeck’s writing and a big part of my recently revised book Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean Avenue . Steinbeck tells the story from the viewpoint of a Dr. Phillips, the story’s Ed Ricketts character, and it contains stark sexual symbolism frequently interpreted by critics in Freudian terms. But did the disturbing incident at the story’s core come from Steinbeck’s imagination, or did it really happen as described? Even Steinbeck’s friends from the time didn’t agree about where he got the idea for “The Snake.”

“The Snake” takes place in a familiar version of Ed Ricketts’ Doc’s Lab on Cannery Row, a frequent venue in Steinbeck’s writing and a big part of my recently revised book Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean Avenue . Steinbeck tells the story from the viewpoint of a Dr. Phillips, the story’s Ed Ricketts character, and it contains stark sexual symbolism frequently interpreted by critics in Freudian terms. But did the disturbing incident at the story’s core come from Steinbeck’s imagination, or did it really happen as described? Even Steinbeck’s friends from the time didn’t agree about where he got the idea for “The Snake.”

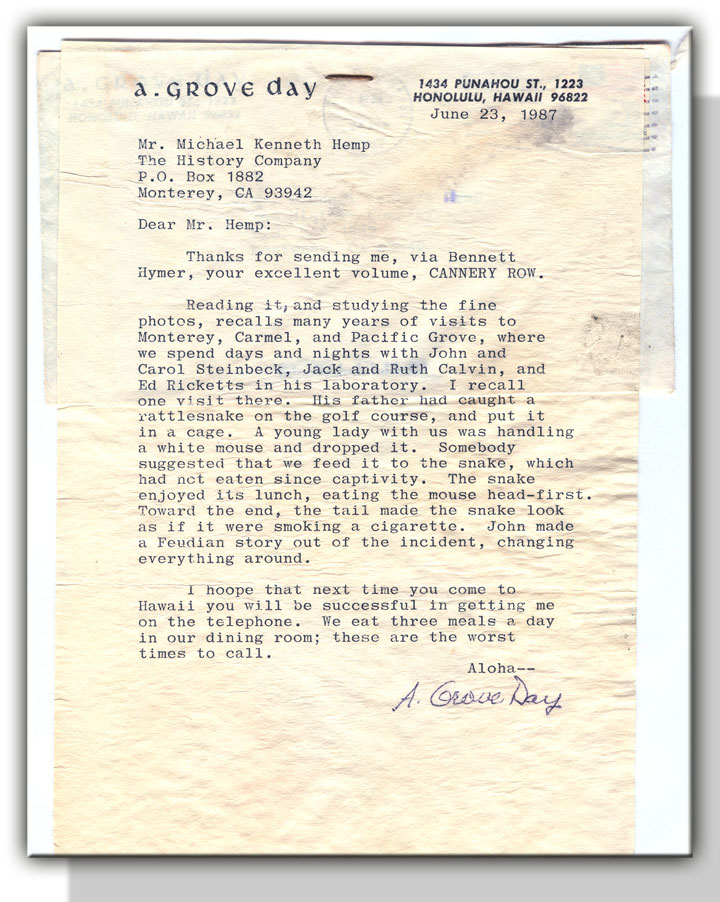

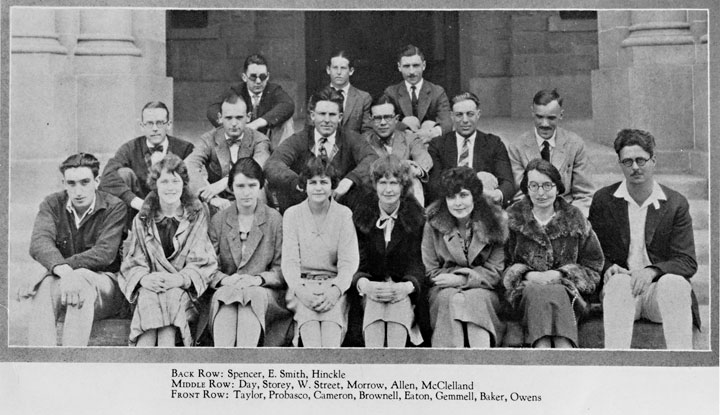

While reading comments by Robert DeMott concerning the context of John Steinbeck’s forgotten World War II story “With Your Wings,” I recalled an acknowledgement letter I received years ago from A. Grove Day, the late historian and biographer who became Steinbeck’s friend at Stanford in the 1920s, where both were members of the famous Stanford English Club. Born in Philadelphia in 1904, Grove died in Hawaii—the subject of his special expertise as a scholar—in 1994. I found his fascinating 1987 letter about “The Snake” in my files, postmarked from Honolulu.

While reading comments by Robert DeMott concerning the context of John Steinbeck’s forgotten World War II story “With Your Wings,” I recalled an acknowledgement letter I received years ago from A. Grove Day, the late historian and biographer who became Steinbeck’s friend at Stanford in the 1920s, where both were members of the famous Stanford English Club. Born in Philadelphia in 1904, Grove died in Hawaii—the subject of his special expertise as a scholar—in 1994. I found his fascinating 1987 letter about “The Snake” in my files, postmarked from Honolulu.

Grove’s letter, which shows his skill as a writer and his knowledge of Doc’s Lab, augments other interpretations of “The Snake,” including those by two other friends from Steinbeck’s Stanford student days, Toby Street and Dook Sheffield. (In this photo of the English Club, Day is seated far left on the middle row; Street sits third from the left on the same row.) Grove’s letter claims that Ricketts’s father—who helped out at his son’s Cannery Row marine specimen business—caught the snake on a golf course and put it in a cage at the Lab, where “a young lady with us” fed it a white mouse as the snake’s first meal in captivity. Sheffield, who became a newspaper reporter, was more direct when he spoke about the story. He claimed that a local showgirl needed the snake for her act, although a rattlesnake would be a dangerous choice for the purpose.

Street commented about “The Snake” in a 1975 interview with Martha Heasley Cox, founder of the Steinbeck Studies Center at San Jose State University. His version possesses the weight of what lawyers call credible evidence and is quoted in full below. At this point in his exchange with Professor Cox, Street mentions “a girl that was on the circuit here [who] took a fancy to Ed.” When asked by Cox to explain what he means by “the circuit” (roadhouse and bar entertainment replacing vaudeville with some burlesque), Street employed a combination of diplomacy and directness developed in his post-Stanford career as a Monterey attorney for clients including John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. Like Grove, Street was as careful with facts as with feelings. When he spoke to his interviewer for the record about “The Snake,” he may have omitted living names, dates, and details.

“They used to have, you know, the piano player and a couple of girls and they’d entertain and they’d go around. And this girl happened to be [at the Blue Bell Café] and took a fancy to Ed, and Ed invited her to the lab. And she was a kind of sexy-looking dame and so while she was there, he said that he had to feed the snake. He had a big cage, quite a big cage full of white rats—and he went in there and selected one and put it in with the rattlesnake. The mouse ran all around, and this girl was just fascinated by the damned thing. And then, pretty soon, the little mouse stopped and the rattlesnake struck. Its fang caught in the mouse. And when he pulled, he brought the mouse back with it, and of course the mouse didn’t pay any attention, just ran around until the toxic effects began to take hold. His back got all rigid, and he stood up on his back feet and when he fell down, he put his paws right on his nose, like that. This girl, by this time, was right up there looking down at that. And the rattlesnake went over, and you know the way they do—they go up and down the body, noticing how long it is and whether it is still alive. Their auditory nerve is on their tongue. It then finally discovered that the mouse was in fit shape to eat. He went over and went through all his business and got his jaws on the edge and took this little mouse in his mouth. And she watched, oh, I think perhaps half an hour, until there wasn’t anything left but the tail of this mouse hanging out of the snake. John made a story out of it and gave it a lot of implications that probably were there.”

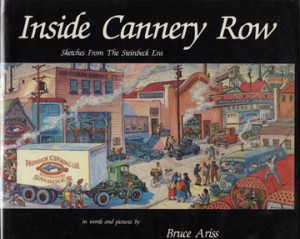

In his way, Toby Street agrees with Grove Day about the story’s Freudianism, as does Bruce Ariss, a Cannery Row legend in his own right. Bruce’s book, Inside Cannery Row: Sketches from the Steinbeck Era, identifies a tweedy, spinsterish dean from an eastern girl’s college as the woman in Doc’s Lab who became excited and told Ricketts she wanted to pay him to keep and feed the snake for her.

In his way, Toby Street agrees with Grove Day about the story’s Freudianism, as does Bruce Ariss, a Cannery Row legend in his own right. Bruce’s book, Inside Cannery Row: Sketches from the Steinbeck Era, identifies a tweedy, spinsterish dean from an eastern girl’s college as the woman in Doc’s Lab who became excited and told Ricketts she wanted to pay him to keep and feed the snake for her.

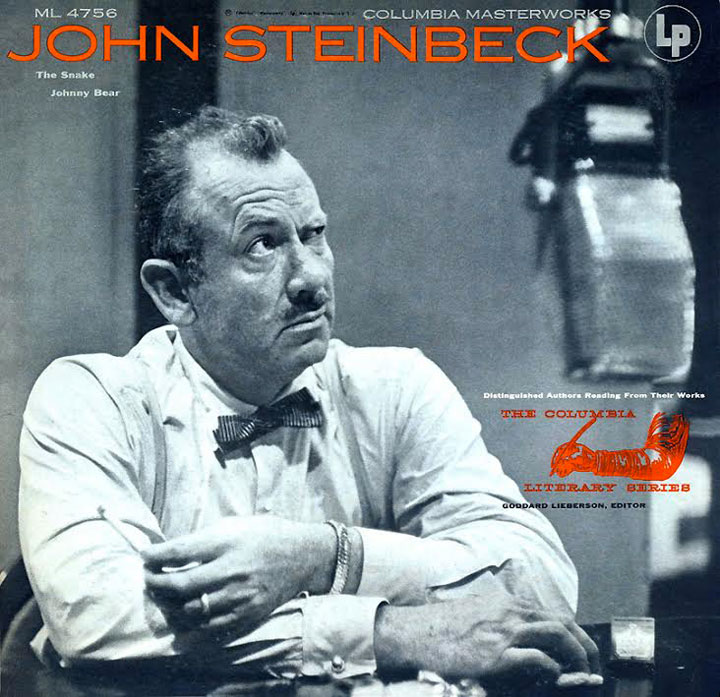

Frank Wright, another friend of Ed Ricketts from the 1940s, introduced me to “The Snake” more than 30 years after Steinbeck wrote his short story. Following Ed’s death, Frank became a member of the circle of men who saved Doc’s Lab, all friends of Monterey schoolteacher Harlan Watkins, who rented Doc’s Lab in the early 1950s before buying it from the Yee family (the real-life family of Lee Chong in Cannery Row). Watkins eventually sold the Lab to Frank and friends, and it was there that Frank first played for me the LP recording of John Steinbeck reciting “The Snake”—a dramatic way for any new reader to participate in Steinbeck’s provocative short story. Brought to life by Steinbeck’s distinctive baritone and experienced where the incident occurred, “The Snake” takes on a powerful feeling all its own. Friends lucky enough to have Frank as their Cannery Row guide continue to enjoy listening to John Steinbeck recite his story while visiting Doc’s Lab.

Frank Wright, another friend of Ed Ricketts from the 1940s, introduced me to “The Snake” more than 30 years after Steinbeck wrote his short story. Following Ed’s death, Frank became a member of the circle of men who saved Doc’s Lab, all friends of Monterey schoolteacher Harlan Watkins, who rented Doc’s Lab in the early 1950s before buying it from the Yee family (the real-life family of Lee Chong in Cannery Row). Watkins eventually sold the Lab to Frank and friends, and it was there that Frank first played for me the LP recording of John Steinbeck reciting “The Snake”—a dramatic way for any new reader to participate in Steinbeck’s provocative short story. Brought to life by Steinbeck’s distinctive baritone and experienced where the incident occurred, “The Snake” takes on a powerful feeling all its own. Friends lucky enough to have Frank as their Cannery Row guide continue to enjoy listening to John Steinbeck recite his story while visiting Doc’s Lab.

Now listen for yourself. Pay particular attention to what Steinbeck says before he recites the story. Though missing from printed editions, the compelling comments Steinbeck makes here about “The Snake” confirm how he liked to cover his tracks in his writing. Using the same phrase (“something that happened”) he employed elsewhere about other challenging subjects in his fiction, Steinbeck makes a funny reference to the sex-symbolism that distressed certain readers of “The Snake” from the beginning: “One of my favorite pieces of fan mail came from a small town librarian. She said it was the worst story she’d read anywhere; she was quite upset at its badness. Actually it isn’t a story at all. It’s just something that happened . . . . ”

Postscript: Steinbeck’s reading of “The Snake” and “Johnny Bear”—another short story from The Long Valley—was released in 1953 as a now-rare Columbia Literary Series record album. As noted, the details about the story’s origin provided by A. Grove Day in his letter differ in emphasis from those offered by Toby Street and Dook Sheffield, whose versions differ substantially from that of Bruce Ariss. As I thought about time and memory, another conversation with a friend of John Steinbeck came rolling out of the past. In 1983 I interviewed the great Joseph Campbell in Doc’s Lab, where he recalled the time “Ed called us all down to the Lab to watch him feed a rattlesnake.” Here is what Campbell had to say about “The Snake” that day on Cannery Row three decades ago.

Postscript: Steinbeck’s reading of “The Snake” and “Johnny Bear”—another short story from The Long Valley—was released in 1953 as a now-rare Columbia Literary Series record album. As noted, the details about the story’s origin provided by A. Grove Day in his letter differ in emphasis from those offered by Toby Street and Dook Sheffield, whose versions differ substantially from that of Bruce Ariss. As I thought about time and memory, another conversation with a friend of John Steinbeck came rolling out of the past. In 1983 I interviewed the great Joseph Campbell in Doc’s Lab, where he recalled the time “Ed called us all down to the Lab to watch him feed a rattlesnake.” Here is what Campbell had to say about “The Snake” that day on Cannery Row three decades ago.

Hi Mike!

Great piece you’ve written here. The story of “The Snake” has intrigued

me for years. I will have to admit that I believed the part about the gal

dressed in black who came to Ed’s door and asked to buy a snake.

Well, I’ll have to say that the story is thought provoking and worth a read

or a listen to. John’s voice of gravel is perfect for the reading and if you

are adept with Internet things, you can hear him read the story.

John was a writer of fiction, guess I’d forgotten that when I listened to his

reading. Fiction it is, not a moment in history as I had thought for some

years. Good story though, a fun reading.

And the working title for the manuscript that would be published as Of Mice and Men was … “Something That Happened” , , ,

Herb