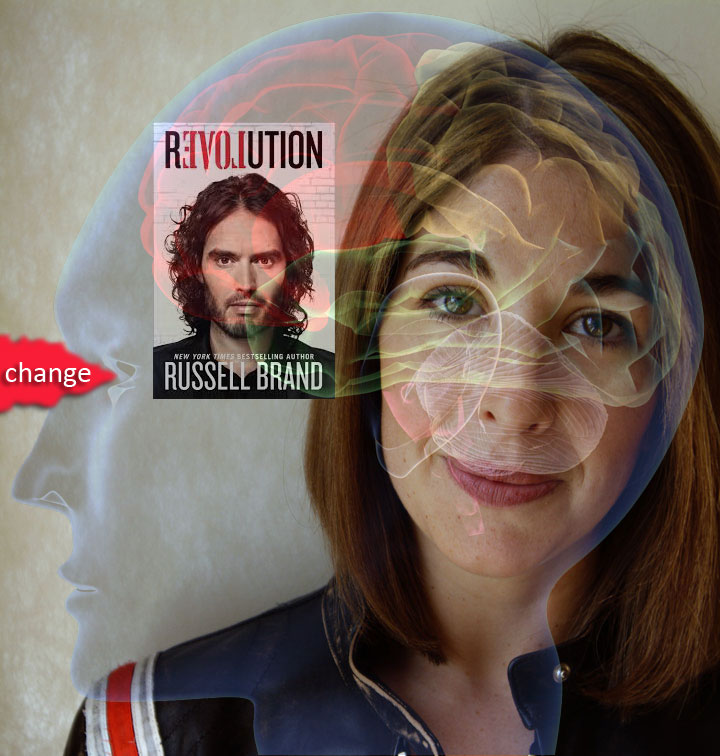

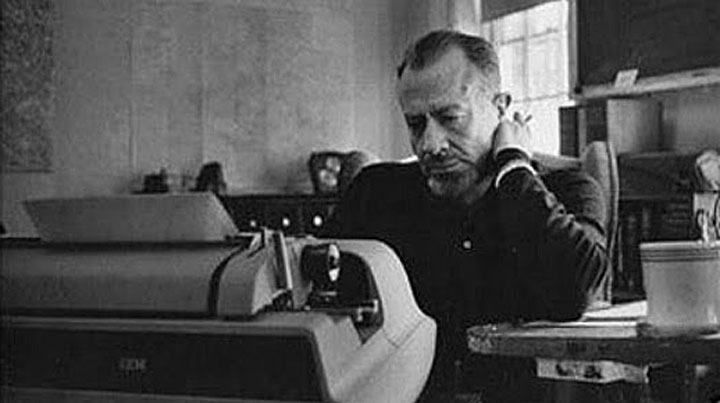

Though he’d probably be puzzled by the media contemporary counter-cultural critics like Russell Brand and Naomi Klein employ to communicate the human cost of mounting income inequality, predatory capitalism, and pending climate crisis—YouTube, podcasts, personal websites—John Steinbeck would likely agree with their call for a revolution in how we think and organize ourselves as a survival-species. I encourage you to read Russell’s Brand’s Revolution and Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything, both published in 2014, if like me, The Grapes of Wrath captivated your imagination and outraged your sense of justice.

Though he’d probably be puzzled by the media employed, John Steinbeck would likely agree with the call for a revolution in how we think and organize ourselves as a survival-species.

Not long after meeting Joseph Campbell—quoted by Brand and Klein in their writing about human belief and behavior—Steinbeck encountered first hand the evidence of destructive income inequality and environmental degradation in the Midwestern Dust Bowl and California labor camps of the Great Depression. The Grapes of Wrath was the result of John Steinbeck’s personal epiphany. Both the struggle and the enlightenment he dramatized continue in our time. Russell Brand and Naomi Klein project Steinbeck’s local vision on a global screen, exposing the noxious roots of global income inequality, climate change, and predatory capitalism—problems that are worse today than when John Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath.

‘The Grapes of Wrath’ was the result of John Steinbeck’s personal epiphany. Both the struggle and the enlightenment he dramatized continue in our time.

As I read Russell Brand and Naomi Klein, it occurred to me that they were really channeling John Steinbeck, even when quoting Joseph Campbell or James Lovelock, the British biologist whose 1960s Gaia theory (Earth as a single organism comprised of interconnected systems) reflects advanced thinking about ecology expressed by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts in Sea of Cortez. For that matter, Tortilla Flat presages the small-group collectivism espoused by Russell Brand in Revolution, and Travels with Charley suggests the same connections between consumerism, conflict, and unhappiness drawn by Brand and Naomi Klein in their books. Events have caught up with John Steinbeck’s prophecy; as I write, his beloved city of Paris remains on security alert following the Charlie Hebdo massacre, and Agence France-Presse reports that the richest one percent of the world’s population will own half of the world’s wealth by next year. Like John Steinbeck, Russell Brand and Naomi Klein wish to advise us of disaster ahead.

As I read Russell Brand and Naomi Klein, it occurred to me that they were really channeling John Steinbeck, even when quoting Joseph Campbell or James Lovelock, the British biologist whose 1960s Gaia theory (Earth as a single organism comprised of interconnected systems) reflects advanced thinking about ecology expressed by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts in Sea of Cortez. For that matter, Tortilla Flat presages the small-group collectivism espoused by Russell Brand in Revolution, and Travels with Charley suggests the same connections between consumerism, conflict, and unhappiness drawn by Brand and Naomi Klein in their books. Events have caught up with John Steinbeck’s prophecy; as I write, his beloved city of Paris remains on security alert following the Charlie Hebdo massacre, and Agence France-Presse reports that the richest one percent of the world’s population will own half of the world’s wealth by next year. Like John Steinbeck, Russell Brand and Naomi Klein wish to advise us of disaster ahead.

Like John Steinbeck, Russell Brand and Naomi Klein wish to advise us of disaster ahead.

Russell Brand’s Revolution—Change You Can’t Believe In?

Mention Russell Brand to anyone under 40—the age the hyperkinetic actor, radio host, and comedian will reach in June—and you’ll likely learn about Forgetting Sarah Marshall and Get Him to the Greek, youth-market movies in which Brand played offbeat characters. I’ll show my own age and admit I didn’t know who Russell Brand was until he was called out by Bill Maher (on Real Time with Bill Maher, soon after the 2014 election) for asserting in Revolution that voting is pointless because all political parties have the same agenda: getting and keeping power and protecting moneyed interests. But watching Maher, I recognized Brand’s face from St. Trinian’s, an offbeat British comedy about an anarchic private girl’s school that I enjoyed. In the movie, Brand plays a hyperbolic drug dealer, Colin Firth is a clueless Tory Minister of Education, and Rupert Everett portrays a playboy dad and—in dreadful drag—the school’s pot-smoking headmistress, who is Firth’s love interest as well. Naturally, I bought Brand’s book.

Mention Russell Brand to anyone under 40 and you’ll likely learn about ‘Forgetting Sarah Marshall’ and ‘Get Him to the Greek,’ youth-market movies in which Brand plays offbeat characters.

When I learned more about Russell Brand, his role in St. Trinian’s made sense. Turns out he’s an up-from-poverty populist with an ability to talk fast, a history of alcohol and drug abuse, and a slight criminal record—sort of an updated character from Tortilla Flat, but with an East London accent. As a thinker Brand firmly believes in benevolent anarchy, the form of social reorganization he recommends in Revolution. As a speaker and writer he manages, like John Steinbeck, to mix high-level messaging with low-level language, similar to the chatty social outcasts who populate Cannery Row. Also like Steinbeck, Brand attributes greed and consumerism to spiritual causes embedded in the human condition. This is where John Steinbeck’s friend Joseph Campbell, the anthropologist of myth-making, comes in handy for Brand, a recovering alcoholic whose 12-step program for curing income inequality (Chapter One: “Heroes’ Journey”) rests on spiritual insights found in the world’s great religions and literature. William Blake, whose visionary poetry particularly appealed to John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, is mentioned frequently in the same vein.

As a thinker Brand firmly believes in benevolent anarchy, the form of social reorganization he recommends in ‘Revolution.’

I marked my copy of Revolution as I read along because so much that Russell Brand says is, like his movie roles, so entertaining. And while he’s perfectly aware of the paradox that he’s trashing capitalism in a product published by an affiliate of the media conglomerate Bertelsmann, it wouldn’t be fair to discourage other buyers by over-quoting from the book. (Also, as Brand might observe, there’s them corporate lawyers, so look out.) Brand’s serio-comic perceptions are memorable because they mix things up, Tortilla Flat-like. Here are a few examples, chosen because they connected with John Steinbeck, Joseph Campbell, Blake, or my funny bone:

“We are living in a zoo, or more accurately a farm, our collective consciousness, our individual consciousness, has been hijacked by a power structure that needs us to remain atomized and disconnected.”

“Campbell said, ‘All religions are true in that the metaphor is true.’ I think this means that religions are meant to be literary maps, not literal doctrines, a signpost to the unknowable, a hymn to the inconceivable.”

“At some point in the past, the mind has taken on the duty of trying to solve every single problem you are having, have had, or might have in the future, which makes it a frenetic and restless device.”

“The alarm bells of fear and desire are everywhere; these powerful primal tools, designed to aid survival in a world unrecognizable to modern civilized humans, are relentlessly jangled.”

“At some Anglican sermon in Surrey, the ‘file-down-the-aisle, handshake-and-smile’ ending is the energetic climax of proceedings. After a polite rendition of ‘Jerusalem’ (in which Blake was apparently being sarcastic) or ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ (which Stewart Lee breaks down beautifully), there isn’t a moment of postcoital awkwardness where everyone thinks, ‘F*** me, we really let ourselves go here.’”

And that’s only from the first five chapters. There are 33 in all, and there are no asterisks in any of them, suggesting a P-13 rating if the book were a motion picture. In a hostile review, The Guardian newspaper dismissed Revolution as “The barmy credo of a Beverly Hills Buddhist.” Then again, the London paper’s online logo boasts that it’s a past “Winner of the Pulitzer prize,” information that Russell Brand would probably identify as a sign of deep-seated corporate insecurity, and that John Steinbeck, who won a Pulitzer for The Grapes of Wrath and disliked self-promotion, would also find deeply unimpressive. Newspapers were economic enterprises with political agendas in Steinbeck’s view, one based on bitter personal experience, and certain media moguls particularly bothered him. The Grapes of Wrath could be characterized as “the barmy complaining of a Los Gatos liberal” and was called worse in print; Steinbeck went out of his way to disparage (without identifying) the ruthlessly acquisitive California publisher William Randolph Hearst, the Rupert Murdoch of Steinbeck’s day. Brand, like Naomi Klein, calls out Murdoch by name for creating the global media machine that protects the interests of predatory capitalism and right-wing politics everywhere: a Citizen Kane on steroids.

The Guardian newspaper dismissed ‘Revolution’ as ‘The barmy credo of a Beverly Hills Buddhist.’ Then again, the London paper’s online logo boasts that it’s a past ‘Winner of the Pulitzer prize,’ information that Russell Brand would identify as a sign of deep-seated corporate insecurity, and that John Steinbeck, who won a Pulitzer for ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ and disliked self-promotion, would also find deeply unimpressive.

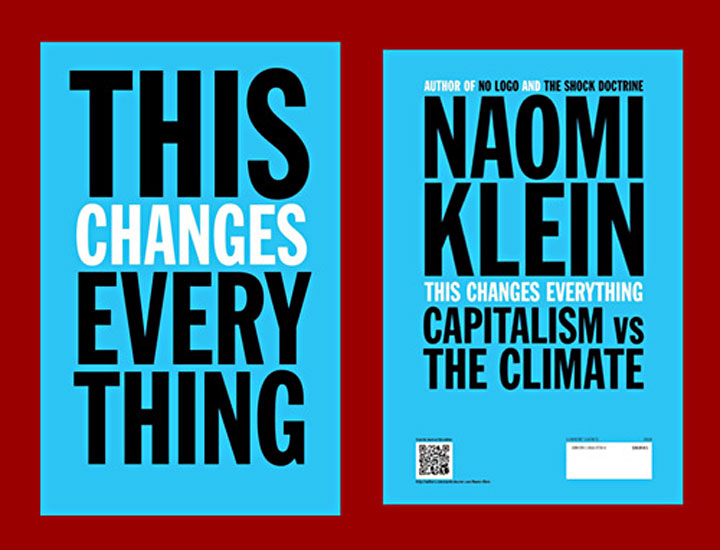

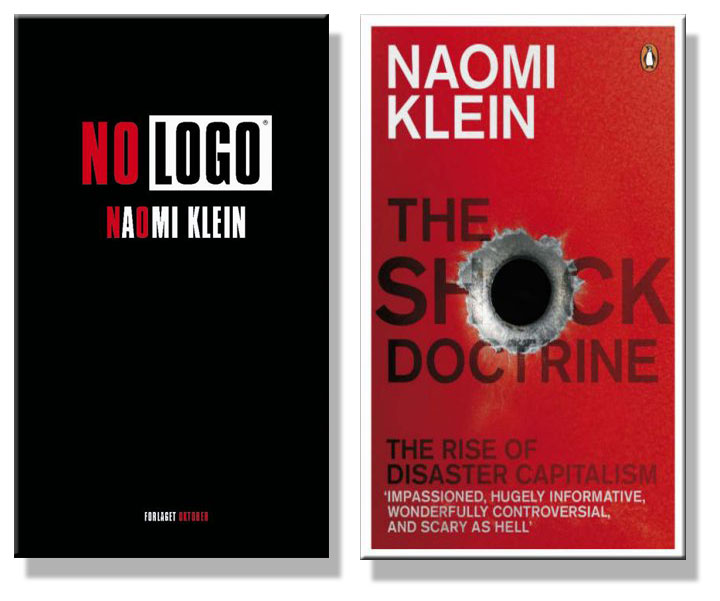

Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Third Hit in a Row

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate got better reviews. The medium is the message, and the book’s careful composition reflects the contrast between Naomi Klein’s polish and Russell’s brand of craziness. He’s hot, hyperactive, and can seem hostile, even with a bath towel draped around his naked neck on his daily YouTube news show, The Trews. Naomi Klein is cool, calm, collected—the daughter of American professionals who left for Canada during the Vietnam War. Brand grew up on the mean streets of East London with a struggling but doting mum and a step-dad. Naomi Klein’s mother is a documentary filmmaker and her father is a physician; both are social activists committed to global causes. In May, Klein will be 45, one month before Russell Brand turns 40. His previous books were wacky children’s stories; hers—No Logo (2000) and The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (2007)—are already considered classics of contemporary cultural criticism. She writes well and she writes often, for The Nation, Harper’s, and—yes—The Guardian; Russell Brand’s mode is oratory, on stage, on radio, and on YouTube. He’s poetry, she’s prose. Other than not bothering to finish college, neither one remotely resembles John Steinbeck in background or personality. But both share Steinbeck’s anger about income inequality, environmental degradation, and social injustice, writing from rage without being inhibited by academic or institutional affiliations.

‘This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate’ got better reviews. The medium is the message, and the book’s careful composition reflects the contrast between Naomi Klein’s polish and Russell’s brand of craziness.

After viewing Russell Brand’s daily Trews segment this morning—a denunciation of military-industrial profiteering and health-service cost-cutting in Great Britain—I dialed back to his October 15, 2014 podcast with Naomi Klein about her then-new book. Her clear, controlled answers to his exuberant questions were just like her writing: comprehensive, linear, and built on solid research, including copious sources, vigorous narrative, and clusters of checkable statistics. The New York Times praised This Changes Everything as “a book of such ambition and consequence that it is almost unreviewable.” The same can be said of Klein’s earlier books. No Logo (“No Space, No Choice, No Jobs”) explores corporate branding from various vantage points—economic, psychological, sociological, political—and turns up a goldmine. The Shock Doctrine connects the dots between Cold War American interventionism, both covert and undeclared (as in Chile under Pinochet), George Bush’s Halliburton-helping invasion of Iraq, and post-Katrina profiteering by firms like Blackwater. Henry Kissinger, the architect of U.S. shock-doctrine foreign policy, and Milton Friedman, the father of free-market economic ideology, receive the close attention the human damage they caused deserves.

The New York Times praised ‘This Changes Everything’ as ‘a book of such ambition and consequence that it is almost unreviewable.’ The same can be said of Klein’s earlier books.

John Steinbeck’s public support for American intervention in Vietnam—pre-Friedman and pre-Kissinger—continues to trouble the author’s admirers. Based on private correspondence, however, there’s little doubt that Steinbeck had his doubts about the war’s wisdom or justification, or that he might eventually have come around to Naomi Klein’s parents’ point of view. He was no friend of torture, assassination, or reactionaries, either; we can be confident that Klein’s compelling critique of Margaret Thatcher’s England, George W. Bush’s America, and Vladimir Putin’s Russia would resonate with him if he were alive. As Russell Brand would say, laissez-faire only sounds like a laid-back street party; it’s actually quite dangerous. As political and economic doctrine, it encourages corporate cronyism, induced-disaster opportunism, and national-security statism on an Orwellian scale. Brand and Klein remind us that the unfortunate evidence can be found on the ledgers of both political parties in the U.S., on both sides of the aisle at Westminster, and in both major post-Communist nations, Russia and China.

Perhaps Russell Brand is right, then: why bother to vote if the outcome will always be the same? As Klein notes, even conservatives make concessions to personal freedom (gay marriage, for example) to keep the public’s nose out of Wall Street’s business, which is avoiding regulation, breaking rules, and increasing income inequality. I know, this part’s a bit confusing, because laissez-faire economics is called neo-liberalism in Europe, rendering the term useless in discussing the economic implications of American politics. (Milton Friedman, the right wing’s Karl Marx, was a neo-liberal. Go figure.) John Steinbeck supported liberal politicians all his adult life—Roosevelt, Stevenson, Kennedy—and he actively disliked neo-liberal conservatives like Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon, who would be considered too moderate by Tea Party members today. I’m pretty sure Steinbeck would argue with Russell Brand about not voting, but I’m equally certain he would agree with Naomi Klein’s analysis of the Arab-Israeli conflict over Palestine, where he wrote some of his most interesting travel commentary before the Six-Day War that changed the political landscape of the Middle East, it would appear permanently.

John Steinbeck supported liberal politicians all his adult life, and he actively disliked neo-liberal conservatives who would be considered too moderate by Tea Party members today.

In a sense, This Changes Everything is a continuation of the cultural narrative begun in The Shock Doctrine. Indeed, Naomi Klein’s books can be read (and I recommend this) as a single meta-story, not unlike the alternating narrative and intercalary chapters in The Grapes of Wrath. The social and environmental consequences of laissez-faire economics—perpetual armed conflict, growing income inequality, cataclysmic climate change—all flow from a singe source in both interpretations of current events: the enshrinement of personal greed as a political philosophy, employing all of the tools that government, media, and private wealth possess to reshape collective consciousness and reify the status quo. James Lovelock, the author of the earth-as-organism theory that I first heard about in college biology, was and is a sunny optimist, now approaching the age of 96. But as John Steinbeck knew, hope can be a commodity too.

In a sense, This Changes Everything is a continuation of the cultural narrative begun in The Shock Doctrine. Indeed, Naomi Klein’s books can be read (and I recommend this) as a single meta-story, not unlike the alternating narrative and intercalary chapters in The Grapes of Wrath. The social and environmental consequences of laissez-faire economics—perpetual armed conflict, growing income inequality, cataclysmic climate change—all flow from a singe source in both interpretations of current events: the enshrinement of personal greed as a political philosophy, employing all of the tools that government, media, and private wealth possess to reshape collective consciousness and reify the status quo. James Lovelock, the author of the earth-as-organism theory that I first heard about in college biology, was and is a sunny optimist, now approaching the age of 96. But as John Steinbeck knew, hope can be a commodity too.

James Lovelock, the author of the earth-as-organism theory, was and is a sunny optimist, now approaching the age of 96. But as John Steinbeck knew, hope can be a commodity too.

When John Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath, Sea of Cortez, and later Cannery Row, war and drought and despair seemed liked passing phases, misfortunes to be confronted and endured and survived. Now, three-quarters of a century later, are we still that sanguine about the future? As Naomi Klein demonstrates in This Changes Everything, the global climate clock is ticking, and the accumulated power of the international petroleum industry prevents the reformation of human belief and behavior required to slow it down. I’m glad she picked Bill Gates and Virgin’s Richard Branson for special scorn in her book. As she shows, each is a wolf in liberal’s clothing when it comes to meaningful action in the current crisis: the billionaires won’t save us when the oceans rise, she proves that for sure. If not reform—as John Steinbeck warned us in The Grapes of Wrath, then what? Revolution?

Thanks, Will, for this information. I have enjoyed your postings and recommendations–always thought-provoking–to say the very least! Keep up your good work!

Thank you, Jim. That’s why we do it!

Now THAT was one hell of an article. Nicely done!! Now I have even more to read.

Thank you, Jody. Your J. Edgar Hoover and Me piece was a hard act to follow.

I was about to go into Walmart the other day to check prices on a television set when a person with a clipboard asked if I’d care to sign a petition limiting the state’s auto license tax. Sure, I said, believing that would be something anyone with a car would find agreeable. But I was wrong, for only a handful of shoppers bothered to stop. As I had time to spare, and since the national election was just around the corner, I decided to intrude by asking a question or two of the refusers. “Are you registered to vote? Are you going to vote in the upcoming election?”

“No”

“Hell no”

“What for?”

“Why?”

“Of course not.”

“Never!”

“Why bother?”

“What’s it to you?”

“Are you a Communist of something?”

The man with the clipboard might have done better elsewhere, but to get a read on what people think of their government and its politicians, querying them outside the doors of one of America’s beloved shopping institutions makes a great deal of sense. It’s there that I found that the vast majority of America’s adults don’t give a fiddler’s damn. That proved to be only too true, for on the day after the election it was found that only 12% of the nation’s eligible voters had bothered to cast a ballot. And in the aftermath, checking the records of those they voted into office, it became woefully apparent that what America’s 12% wants is a quick return to the era of the Robber Barons and self-enslavement. With 88% of the population asleep and adrift, apart from thinkers like Naomi Klein (and Thom Hartman and Senator Bernie Sanders, and a slight handful of others), what this country needs is its own Russell Brand. And thanks to Will Ray for helping to sound the alarm!

Mr. Smithback,

In agreement with your views, I would like to ask a question about where the blame lies regarding low voter turnout. Apathy and disenfranchisement seem to be rampant, judging by your anecdote and the statistics you cite. That is my take too.

But should we also ask after the cause of that apathy? Is low voter turnout a cause of disenfranchisement or a symptom? (I suppose that is an obvious question. Disenfranchisement is clearly a symptom and I would argue that it is not simply attributable to voter-originated apathy.)

Legislation, like so many cell-phone contracts, is written in a way that is ridiculously and, perhaps intentionally, verbose to the point of obscurity. Open a voting guide to read the legislation you are voting on and if you don’t fall asleep it is only because of the fact that your heart rate has risen running back and forth to the dictionary so much or because you can’t fall asleep tied up in such amazing knots of legalese language.

Hypothetically, can we say that readable legislation might make for a more engaged electorate?

If the language of legislation is actually not meant to insulate the legislature from an easy and open examination from the public, it does a good job of that insulation nonetheless.

Does this line of reasoning excuse low voter turnout? I would say no. It doesn’t But, if we want to get worked up and go all Russel Brand on this issue, I think we have to spread the blame and look to the various causes of disenfranchisement.

I would guess that you might agree on this. I’m not saying anything here that disagrees with your points, I think. Just taking one of the next logical steps in thinking about the nature of the problem you are addressing.

Cheers.

Fascinating. I’ve been a fan of Joseph Campbell for years, and it’s encouraging to see “younger” seemingly somewhat mainstream folks like Brand actually know who he is. I sometimes think Campbell’s wisdom holds the secret to our salvation as a species.

I’m so glad you pointed out the two books. They’re on my list of “to reads.”

Jane Ann

What an interesting article. Just a suggestion regarding the title of the book, “The Sea Of Cortez” by Steinbeck/Ricketts, it should not be confused with the non-fictionok, “The Log From The Sea Of Cortez.” The former is a detailed scientific record of their exploration of the Gulf of California, and includes specimen catalogs and etc.while the “Log” is a philosophical record. The “Log” is one of my favorite fun to read Steinbeck works.

When I think of Steinbeck and the challenges of influencing social change, I think about his “The Moon Is Down” and the problems faced by Colonel Lanser in the book as he attempted to influence the small Norwegian town. To achieve his objectives, the colonel didn’t buy advertising spots, or post slogans on silk screened T-Shirts. He went directly to the individual he thought would best influence the little town, the elected mayor. Readers of the little book will recall that there was a collaborator or Quisling in the village who supplied information to the invading force planners prior to the action. I would expect that the complete intelligence package would have included the fact that there is quite a social difference between a community or a MOB made up of citizens who have surrendered their wills to father figure dictates and one comprised of evolved independent minded individuals like the one described by Steinbeck in his little book. It would surprises me that the spy/collaborator in the little book did not place this social fact in his disclosures. Perhaps he would have and the invasion planners simply did not understand the point as they came from a society ruled by father figures like a NAZI regime.

How easy Colonel Lanser’s life would have been if he had invaded a village of barely conscious individuals who, like aboriginal tribe members, leave all of their judgments and decisions up to the chief or medicine person. Still the basic idea of getting through to the collective, village, MOB, or phalanx via an individual is the most effective and economic. Doing so well requires a better understanding of social bodies and the relationship to individuals. The process of broadcasting oughts and musts to the collective enjoys no greater return than direct mail advertising which is always less than one percent. Hopefully the leadership of the Democratic party awakened to their failings in the previous election. It did not escape my attention that the victorious Republicans in North Carolina did use a NASCAR driver legend to suggest a winning candidate. Meanwhile Democrats were trying to unload friggen printed T Shirts.

The selfless, grand schemed, usually introverted intuitive feeling individuals (INFP in the MBTI) typical to altruism and do gooders must awaken to the fact that influencing social change requires soundly developed terminal and enabling objectives, a clear path between where the objective seekers are and where they will be, and sound processes necessary to achieve the goal. Details, effective and economic steps and processes– not friendly conceptual territory to the more lofty INFPs.

So I am suggesting that a wholesale change of philosophy is required to effectively and economically influence social change and the article, as nice as it was to read, did not give me much hope for future efforts.

Wes Stillwagon

Lillington, NC, USA

Thank you for making compelling connections between Steinbeck’s social vision and the recent books reviewed here; they are deeper and sharper than those that I drew in my remarks. Your acute reading of Carl Jung, another influence on Steinbeck frequently cited by Russell Brand and Naomi Klein in their writing, supports your analysis convincingly. All points well made and well taken.

Thank you Dr. Ray,

I appreciate your kind words. The ideas behdind my opinion/observations are not simply a product of my reading Jung but also a result of reading Jung’s ideas as they were deftly applied by Steinbeck. I then formed rational philosophical skeleton structures so that I could apply them in my work and life. As the idea forms evolved in my brain, I used them in critical skills training program development challenges where they proved their value in better performance of individual trainees and teams in profit centered organziations and partnerships. They repeatedly demonstrated value and benefit over the usual approaches.

Our nation is currently facing a crisis like that of the time previoius to president William McKinley (January 29, 1843 – September 14, 1901) when it was commonplace for the superwealthy like J. P. Morgan, Rockeffeller, Vanderbilts, and Etc. to buy politicians and their votes. Again we see that the average citizen still has not accepted citizenship responsibility or has surrendered his or her influence to those who deceptively promise fatherly care. Anti-trust and other checks and balances were not in place at that time and in-fact those very protections as well as those of our constitution are under attack by the likes of the Koch brothers. The decent people who care about their country are NOT responding well in political campaigns because they lack the knowledge necessary to effectively influence social change. The necessary conceptual models and language are not commonly understood but clear examples exist in Steinbeck novels and non-fiction.

I will see my 75th birthday this year. I worry that the huge number of lessons I’ve acquired will not be carried on and built upon I possibly have two semesters of learning objectives for a class of students wishing to carry on and build upon the concepts. I’d like to have a sponsor to support building the ideas into a worthwhile education and training experience.

Thank you. This is stimulating indeed. Is anyone up for Wes Stillwagon’s challenge?

Just to sweeten the pot, A Steinbeck/Jung Program would include Learning objectives about the following topics:

A More Complete and Useful Models of the Individual Human Psyche

Persona, Ego, the Self

Consciousness and Unconscious

The Development of the Individual

Stages of Evolvement

Psychological Types and Attitudes

Problems of Self Realization

Humans and Their Relationships To Others

Man and Woman

Youth and Age

The Individual And The Community, MOB, or Team

The Shadow,

the Phalanx, and

the Collective Unconscious

World of Values

Awareness and Creative Living

Good and Evil

The Spirit

Ultimate things

Western vs Eastern Points of View

Holism

Teleogical and Non-Teleogical thinking

Fate, Death, and Renewal

Synchronicity, An Acausal Connecting Principle

Text extracts from (Steinbeck) The Log From The Sea Of Cortez; Bombs Away, The Story of a Bomber Team; Cannery Row; Sweet Thursday; In Dubious Battle; and The Moon Is Down; (Jung) The Structure And Dynamics of the Psyche; Psychological Types. Civilization In Transition

Thank you for the thought-provoking article, William!

The idea of building a politics from the work of Joseph Campbell and William Blake is really fascinating.

There is a real power in poetics, I think, though when it comes to keeping billionaires in line (as Klein would do – and for good reason), one has to wonder just how Songs of Innocence might curb the corporate hunger of the profit-hungry-by-definition, publicly traded companies that these billionaires run… Although corporations are seen as “people” by the American justice system when it comes to campaign donations, are they educable “people”? (I don’t say this as a cynic, but as a frustrated liberal who tires quickly of political rhetoric from both/all sides.)

The question of how to teach a corporation about moral, spiritual and ecological ideas seems like a fairly big one in this context. (Who is doing the teaching? Who is doing the listening and learning, on the most practical and actual level?)

Do Klein and Brand answer this question in their books? Are their books, in essence, intended to be answers to this question?

Having seen Russel Brand interviewed on political issues in the past, I find that I tend to agree with his anger but find myself hoping for something more constructive than just attitude. (Offering complaint without leadership is roughly equivalent to simply offering attitude, right?) I take it that in his book, he does go so far as to offer positive ideas for how a revolution in our political and economic thinking might take place.

Without having read the book but after reading your article here, William, I am left wondering if Brand (and Klein too) are advocating for more government or less…

Do we need to regulate big business via a more truly representative and sensitive government body or do we need to boycott, demonstrate, and make our own way as small communities and social collectives or something?

How are we supposed to act on our anger and just what are the politics of Campbellian-Blakean spiritual thought?

Since both of these thinkers looked to a reality that is deeper than the physical, “gross” body to a greater truth of Being (one that precedes and supercedes the “rational world”), the task of translating their theory into political action seems like a necessarily creative one. I hope to pick up Brand’s book, thanks to you, William, and see how he makes that translation.

Cheers!

Eric, you intuited Brand’s vision beautifully, even without reading the book, which I recommend. Brand’s Revolution begins within–a Blakean conversion of individual consciousness reflected in democratically organized groups of like-minded souls who will replace hierarchic government as the basic unit of social organization. Creative anarchy! On the other hand, Naomi Klein calls for greater government strength in areas of economic and environmental justice, which like Brand she sees as inextricably entwined. Brand wants power devolved to freely organized groups of people without political parties or leaders; Klein supports grassroots pressure-movements to make existing governments behave better. Both oppose the claims and aims of capitalist-globalism, and neither would consider a corporation a person in any meaningful human sense–except, as Brand insists, that corporations should die when their time of usefulness to people is past. As I suggested, John Steinbeck would understand Brand and Klein’s vision and vocabulary because he read Eric Fromm, the root source of Brand’s radical perspective and the champion of ‘being rather than having’ as our life-purpose, and because he experienced the collapse of classical capitalism in the 1930s. When Mitt Romney claimed that “corporations are people too” (see John Bell Smithback’s poem of the name at this site), I asked myself the same question you pose in your comment. If they’re people, where’s their conscience, soul, or ethical accountability for their behavior? Naomi Klein’s first book, “No Logo,” is eloquent on this subject, so when you read her start there. Meanwhile, thank you for your thoughtful questions and perceptions–always acute and apropos. Please write a guest-author piece about this when you’re ready. Blake would be a fine starting point.