In the 1980s, it was E.M. Forster. In the 90s, Jane Austen and Henry James. Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and Hemingway had their turn, along with writers of B-list bestsellers whose names have faded, like the films made from their books. In 2015, Hollywood’s Favorite Author is the American Nobel Laureate John Steinbeck. Again.

The Roots of the Recent John Steinbeck Renaissance

Interest in Steinbeck is surging. Steven Spielberg is reportedly preparing a remake of The Grapes of Wrath. Jennifer Lawrence has signed on to play the lead in East of Eden. Recently the actor James Franco, who starred on Broadway last year as George in Of Mice and Men, announced that next month he will start filming an adaptation of Steinbeck’s little-known 1936 novel In Dubious Battle.

Interest in Steinbeck is surging. Steven Spielberg is reportedly preparing a remake of The Grapes of Wrath.

This isn’t Steinbeck’s first trip to Hollywood. Between 1939 and 1957, eight of his books were made into movies, and he wrote original scripts for four more. The best of these films became classics, like John Ford’s Grapes of Wrath; Lewis Milestone’s Of Mice and Men; and Elia Kazan’s East of Eden.

This isn’t Steinbeck’s first trip to Hollywood. Between 1939 and 1957, eight of his books were made into movies.

But these films were made more than half a century ago. When John Ford’s movie of The Grapes of Wrath debuted in 1940, just a year after Steinbeck’s novel was published, the Dust Bowl was still in the news. How do we explain the Steinbeck Renaissance of 2015? What is it about Steinbeck’s work that resonates with us today?

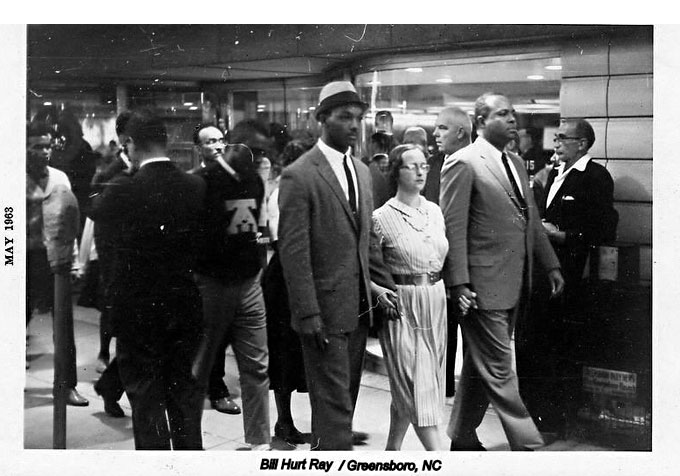

From The Grapes of Wrath to Ferguson, Missouri

The answer is a sad comment on our times. Many of the issues Steinbeck addressed in novels like The Grapes of Wrath are as relevant today as they were 75 years ago. Police abuse, for example, continues to be a major problem in America. As we demonstrate solidarity with the victims in Ferguson, Staten Island, and too many other communities, it’s hard not to think of Tom Joad’s famous line from his farewell speech: “Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there.”

Many of the issues Steinbeck addressed in novels like The Grapes of Wrath are as relevant today as they were 75 years ago.

Our society also still discriminates against migrant laborers. The undocumented workers who harvest our fruits and vegetables are today’s “bindlestiffs,” as Steinbeck called the laborers George and Lennie in Of Mice and Men. Our politicians talk about immigration reform, but nothing ever happens, and as we argue, produce rots in the fields and those laborers who dare to remain here illegally live in constant fear of deportation. I wouldn’t be surprised if this surprisingly modern conundrum is what drew James Franco to In Dubious Battle, a novel about a farmworkers’ strike in California.

Our society also still discriminates against migrant laborers. The undocumented workers who harvest our fruits and vegetables are today’s ‘bindlestiffs.’

But there’s one more reason Steinbeck resonates today. He famously said that his job as a writer was “to reconnect humans to their own humanity.” In this era of braggy Christmas letters and sanitized Facebook personas, it’s easy to forget that when we suffer, we are not alone. Steinbeck showed us humanity in all its forms, not only the happy family on vacation, but the poor and dispossessed, the filthy, the starving, and the mad. It’s no subject for a Facebook post, but it never goes out of style.

Mr. Taylor,

Your piece is thoughtful and compelling. I find that I agree with your conclusion especially – the core of Steinbeck’s work was not political or topical, but essentially human.

He is a writer who remains relevant, in my estimation, because his writing expresses the non-historical, non-political notion that the individual will always struggle to balance the Self against the will of a larger collective. This is true whether the collective is a labor union, as in the case of IN DUBIOUS BATTLE, or in case of a small fishing village, as in THE PEARL.

Perfect unity with the collective is an ideal in Steinbeck that is always accompanied by deep compromises. As fodder for protest and for activism, Steinbeck’s writing certainly speaks for the downtrodden and condemns any system that would crush the poor to serve in the interests of the rich. But I would offer some pushback to your assertion that the police brutality aligned with a ruling class in THE GRAPES OF WRATH is essentially parallel to the police killings that have spurred outrage in recent months.

While each issue of police brutality is tied to an abuse of power that relates directly to an idea of unequal protection under the law, don’t we have to note that in 1939 the police were taking action against the poor to protect an establishment, acting as tools of a system. Can we say that about what happened in Ferguson?

The current issue is one where law enforcement is not acting on behalf of an establishment – not in good conscience anyway. The legal insulation of the officers who have killed unarmed black men is as big a part of this story as the issue of unequal protection that these instances of police violence raise. Was that part of what Steinbeck wrote about?

Again, I agree with much of what you say in your piece. My intention here is to pose the question as to whether or not Steinbeck remains relevant because of the political views he expressed in the 30s, 40s and 50s or if he remains relevant for the point of view that informed his politics – an apolitical sense that the honest man is constantly engaged in a high-wire act on the ever-narrow bridge stretched between individual identity and the urgencies of his society.

I will be the first to admit that there is no taking the politics out of Steinbeck’s work. But I wonder if we can take Steinbeck out of politics and, if we do, see the writer as an artist and not as a politician. As a Van Gogh as much or more than as a Thomas Paine.

That’s my two cents. (And I recognize that my point is debatable. Just putting it out there.)

Nick,

I just finished rereading Travels with Charley, and the last part of that book – integrating New Orleans’ schools – and your piece, made me think back to Ferguson, Missouri. I wrestled in high school, for Kirkwood High, and two of the schools in ou rleague were/are located in Ferguson, Ferguson and Normandy highs.

As has been pointed out numerous times since the August Ferguson shooting and riots, Fegruson used to be an overwhelmingly white community. But there were some blacks, and I remeber, for several reasons, two black brothers who wrestled for Normandy. As I recall their last name was Simpson. Well, the Simpsons didn’t know me, but knew of me, and the same was true of me knowing of them. Both were excellent athletes, handsome and smart.

A year or so later, as a freshman at the University of Missouri, I was out late one night with friends when we were cornered and threatened by some gang types. Along came walking the Simpson brothers. One recognized me – wrestlers are a kind of fraternity, in the good sense of the word – and the brothers, at great risk, interjected themselves between us and the gangers, who vacated the scene.

This was in the same era Steinbeck was traveling through New Orleans, and I think back how lucky I was that two black guys saw fit to come to our rescue at the same time whites were harassing black kids in New Orleans, much to Steinbeck’s sorrow.

So in addition to finding Steinbeck a great writer and writing about him, I suddenly realize I have a kind of ironic connection to him, having a good racial experience while he was having a bad one. Thanks for helping me realize that.

By the way, watching the television coverage of Ferguson, I wonder if the Simpsons returned and live there. If so, I hope they weren’t damaged in any way.

Brilliant work, Nick. Lines like this find their mark: “But there’s one more reason Steinbeck resonates today. He famously said that his job as a writer was ‘to reconnect humans to their own humanity.’ In this era of braggy Christmas letters and sanitized Facebook personas, it’s easy to forget that when we suffer, we are not alone.” I’m not a fan of separating Steinbeck’s politics from his work. I would suggest that his expansive sense of humanity cuts to the heart and encourages hope, even today.

Hello Roy,

Would you say that an expansive sense of humanity is political? Certainly a positive sense of human potential is encouraging and hopeful, but how is it political? That is where I get hung up.

There seems to be a rather loose definition of politics at work when we suggest that a single political issue animates the action of THE GRAPES OF WRATH and police violence in 2014, or when we say that Steinbeck’s humanism is essentially a political point of view.

If this is our definition of politics, doesn’t everything end up being political? And if we say that all uses of violence are derived from the same political issue, aren’t we promoting a very broad and non-specific view of these events? To say that every instance of police violence against unarmed civilians is derived from the same political issue seems similar to saying that Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Lennon were killed for the same (political) reason. The were both assassinated, but does that mean the act is politically identical in one shooting and the other?

All I am arguing here is that certain readings of Steinbeck’s politics seem to apply a political sensibility that looks like a slippery slope toward an all-embracing usage of the term “politics.” I am not arguing that there is no political content in Steinbeck’s work, of course. What disturbs me, albeit mildly, is the notion that an artist’s vision can be so easily co-opted and even ignored because the surface elements of the work superficially resemble those of other situations.

If we take away some hope from Steinbeck, is it really a political hope?

Mr. Taylor’s piece is clear, nicely written and compelling. I am with you in your praise of the piece and in your appreciation of the conclusion as an outstanding moment. I suppose I just find this one point debatable and so I’ve pursued a debate.

I wonder if you would find some agreement with the idea that we might fruitfully apply Steinbeck’s artistic vision (the expansive humanism you mention) to political situations without saying at the same time that this positive humanism is essentially political in nature.

Maybe this seems like too much of a stretch from your point of view. From mine it seems like a way to keep Steinbeck in the political conversation without re-shaping the idea that politics refer to specific, policy-oriented ideas.

Respectfully,

Eric

Steinbeck writes from the perspective of informal networks and the power of the individual within those networks. I glean from his writings that he sees power as the ability of the individual to predict, participate in and control their environment in a manner that prevents intrusive formal systems from imposing their will on the people. The Moon is Down is a classic example of how he saw citizens in informal networks deal with the oppressor, a top down formal systems German commander with a mission. There was no way to go power on power with the occupiers so Steinbeck created a way for the people who were to be oppressed to prevent that from happening. The people were to be oppressed but they had other ideas about the occupation.

The Nazi Officer advises the Mayor to “think for” his people. The Mayor “thinks with” his people:

“Please co-operate with us for the good of all.” When Mayor Orden made no reply, “For the good of all,” Lanser repeated. “Will you?”

Orden said, “This is a little town. I don’t know. The people are confused and so am I.”

“But will you try to co-operate?”

Orden shook his head. “I don’t know. When the town makes up its mind what it wants to do, I’ll probably do that.”

“But you are the authority.”

Orden smiled. “You won’t believe this, but it is true: authority is in the town. I don’t know how or why, but it is so. This means we cannot act as quickly as you can, but when a direction is set, we all act together. I am confused. I don’t know yet.”

“Lanser said wearily, “I hope we can get along together. It will be so much easier for everyone. I hope we can trust you. I don’t like to think of the means the military will take to keep order.”

Orden was silent.

“I hope we can trust you,” Lanser repeated.

Orden put his finer in his ear and wiggled his hand. “I don’t know,” he said

Power shifted by virtue of Steinbeck’s ability to distinguish informal from formal systems in society throughout his writings. Tom Joad’s statement is a clear example of Steinbeck’s understanding of individual power and its function and influence. From an individual power perspective his statement resonates as much today as when it was written.

We have come once again in our history with Steinbeck to the point of citizens engaging the formal society to create social capital and social justice. In Ferguson, you have the government being the establishment, acting as Lanser does in the Moon is Down. The citizens immediately shifted from an individual one-on-one confrontation to the formation of a MOB as Mack discusses in Cannery Row. The MOB has a mind of its own and in Steinbeck’s interpretation becomes a Phalanx, a unconscious complex drawn together by way of a common held objective. Once this phenomena takes place the dynamics of the confrontation change from the individual to the collective Phalanx. Formal systems, as Steinbeck’s writing reflects, do not recognize this shift in power. Ed Ricketts would call it non-teleological thinking or breaking through and it only takes place in informal systems.

As I have experienced Steinbeck in my pursuit of understanding his social ecological concepts he did not write from a political perspective, but his writing about individual power has enormous political implications in the arena of building social capital in a society.

The writing of John Steinbeck is founded on sound philosophical and scientific social and psychological principles and our societies mainly consist of beings just starting on the path of individuation, his work should continue to be considered a valued intellectual resource. His fiction offers a lucid display of the principles and concepts of individuals engaged in everyday life challenges. The bully cop he wrote about in ‘about Ed Ricketts” has the same psychological issues as the cops under indictment in Baltimore Maryland. MOB behavior talked about by Mac in “In Dubious Battle” is visible in today’s MOB violence. MOB behavior continues to contrasts dramatically with that of the will of the individual participants. These are not new ideas or should they be unexpected observations. I am quite certain Mac would have expected no less in Baltimore Maryland or Ferguson Missouri.

It is obvious to me that we’ve learned so little from recent history. Even the events that had considerable associated pain and suffering haven’t produced much in the way of individual awakening or even the necessary goading desire. After all it isn’t the MOB or Steinbeck’s phalanx that must be directly influenced. The only way the MOB may be influenced is through the individual human psyche. Understanding the individual human psyche requires different models, concepts, and language than that used in statistical or behavior based psychology.

Yes Steinbeck’s writing is a powerful resource for change but it doesn’t look like we are ready for the important lessons they offer. The ideological paranoia being expressed in Texas these days proves my point. Jung said such ideology is the source of the Anti-Christ. Perhaps it is the responsibility of more evolved Steinbeck fans to build better lesson plans and paths between individual and social problems and the philosophical foundation of his work.

Lillington, North Carolina, USA