Plans to publish a new John Steinbeck biography by William Souder, a Pulitzer Prize finalist for Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America, received wide attention for good reason. When Souder’s John Steinbeck biography is released by W.W. Norton & Company in 2019, Jackson Benson’s classic life of Steinbeck will already be 35 years old. Jay Parini’s 1995 John Steinbeck biography covered some of the same ground, but Benson’s experience with Steinbeck’s heirs may have intimidated other biographers, delaying reinterpretation of Steinbeck’s life and work for contemporary readers more interested in new information than old quarrels. On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson, Souder’s brilliant biography of the crusading ecologist who wrote the 1962 book that made environmentalism a burning issue, promises to connect ecology, Steinbeck, and the so-called American century, renewing appreciation and deepening our understanding of a troubled writer who seemed, almost equally, behind and ahead of his turbulent time. Like John James Audubon, John Steinbeck was a complicated man who sometimes managed to cover his tracks. Like Rachel Carson, Steinbeck was a passionate dissident who championed change, challenged power, and suffered the consequences. In this interview, William Souder explores the connections and compares the three figures, explaining why (and how) he is writing a new John Steinbeck biography now.

WR: Your John Steinbeck biography will be titled “Mad at the World: John Steinbeck and the American Century.” How was this title chosen, and what does it tell us about your approach?

WS: Titles are important. Sometimes it comes to you easily at the start, and other times you struggle to find the right one. With Steinbeck I had this title almost from the moment I decided to write about him. There’s the obvious meaning—that Steinbeck wrote in response to the injustice and evil he saw in the world. That’s clearly true in books such as In Dubious Battle, The Grapes of Wrath, East of Eden, and The Winter of Our Discontent, a book I regard highly, and that contains some of Steinbeck’s most elegant prose. Of course, most writers concern themselves in some way with the ills of the world. Steinbeck seemed to take it more personally. He was, especially when he was young, prickly. Not bad-tempered, but running a couple of degrees hotter than everyone else. He bridled at conformity—his deep friendship with Ed Ricketts was based in large part on their shared hatred of convention. Steinbeck didn’t like school, didn’t like Salinas, didn’t like working as a reporter in New York. And all of those things didn’t like him back. Stanford was happy to be rid of him when he finally gave it up. Later, people in California thought The Grapes of Wrath was obscene and filled with lies. Steinbeck pretended to ignore criticism, but no writer actually can. When he said he didn’t think he deserved the Nobel Prize I don’t believe he really meant it. I think he just wanted to disarm the critics who were lining up to say as much. Of course, they said it anyway.

One of the things that attracted me to Steinbeck is that he was far from perfect—as a man, a husband, a writer, he had issues. He had a permanent chip on his shoulder. He got sidetracked by ideas that were a waste of his time and talent. Some of his work is brilliant and some of it is awful. That’s what you want in a subject—a hero with flaws. Steinbeck was a literary giant who wouldn’t play along with the idea that he was important. I love that. He was mad at the world because it seemed somehow mad at him.

Anyway, I think it’s a strong, provocative title. And I hope it explains that I want to place Steinbeck firmly in the historical context that was the wellspring for so much of his work.

WR: Like Steinbeck’s father, you spent your early life in Florida but moved away. Where, when, and how did you become a writer?

WS: I did grow up in Florida, but I was actually born in Minnesota. My dad was an aerospace engineer, and we moved to Florida when the space program got going in the late 1950s. I loved it there, the beaches and the Gulf of Mexico, and the scent of orange blossoms in the warm night air. Florida will always be home to me, but I’ve lived in a lot of places. I married a girl from St. Paul and once you do that you’re committed to the tundra. I’ve been in Minnesota now for longer than anywhere else. It has a lot going for it, though in the winter it’s like living on another planet. We’re out in the country, with the coyotes and the wide open spaces, and the dark, dark starry nights. Our neighbor still cuts hay on our property. But we can see the Minneapolis skyline from our house—in fact I’m looking that way right now.

I got interested in film and photography and writing after I got out of the Navy. I went to the journalism school at the University of Minnesota, which at the time was among the best j-schools in the country, and where you could study all of those things. This was right after Woodward and Bernstein had turned journalism into a glamorous profession. There was a legendary professor there named George Hage—he’s long deceased, but still remembered here as an inspiration to several generations of journalists—who was a mentor to me and who convinced me to become a reporter. Which I did. Then, in 1996, a story I wrote for the Washington Post turned into my first book. I was 50 when it came out four years later and I didn’t look back.

WR: Your first book was about a local ecological catastrophe. How did that lead to writing a life of John James Audubon, who could hardly be characterized as an environmentalist?

Let’s pull the curtain back. For many writers, it only looks like one book naturally follows another. The truth is that, in between, there are often false starts and dead ends. Ideas that don’t pan out. Concepts that your agent or your editor—or both—don’t like. I’ve sold four books to publishers, but I’ve had probably twice that number rejected, though most of them in the early, talking stages, when I had little invested. Some of those ideas probably deserved to die, but with others I wonder what might have been. At one point I was determined to write a book about hurricanes. I had plenty of firsthand experience with hurricanes growing up in Florida, and I wanted to get inside a big storm by flying with the Hurricane Hunters out of Miami. But my editor didn’t think it would work and I moved on. Later that year, Katrina hit New Orleans.

My interests are science—especially biology—the environment, history, and writers. So I look for subjects that embody those interests. That’s the common thread in all of my books, and it applies to John Steinbeck, too. It’s true that Audubon was no environmentalist. Nobody was back then. But he was, in addition to being a great painter, a naturalist and explorer and ornithologist who was immersed in what we call “the environment,” which is really just the world as it is—including the damage we do to it.

WR: Your biography of John James Audubon was a Pulitzer Prize book finalist. Winning the Pulitzer Prize seemed to surprise Steinbeck and disrupt relationships in his life. Did making the Pulitzer Prize short list influence your choice of subject for your next book?

WS: Being a finalist for the Pulitzer means your book was one of three nominees for up for consideration. One book wins, the other two are the finalists. So it’s a select group and an honor. And it did have one important effect on my future work: It confirmed for me that I could write biography, a discipline I didn’t know anything about until I did the Audubon book, but which I fell in love with. It turns out that I have that gene that makes you willing to spend weeks or months in an archive crawling around inside someone else’s life. And when you do that, and that other life becomes a story you have to tell, you know you’re cut out for biography.

You do choose your subjects. Absolutely. And there can be a lot of calculation in it. You’re searching for a book that you want to write and that people will also want to read. But for it all to come together, on some level your subject has to choose you. I started thinking about writing about Rachel Carson around 2005. But I wanted to time that book so it would come out in 2012, on the 50th anniversary of Carson’s Silent Spring. I figured I had time to write one, or maybe two other books before turning to Carson. But a couple of ideas didn’t work and by 2008 I realized it was time to start on Carson. She left a rich paper trail—most of it is at the Beinecke library at Yale, one of my favorite places in the world—and the more I looked at the material the more insistent it became. Once someone’s life gets inside your head you can’t shut it off. It’s like hearing a voice. Let’s do this now.

WR: Your John James Audubon book is also a biography of frontier America’s adolescence. What motivated the leap from 19th century to 20th century America in your decision to write about Rachel Carson?

WS: In my mind, Audubon and Carson have deep connections to each other. Audubon recorded, in his remarkable bird paintings and in what he wrote to accompany those images, an American landscape largely unmarred by civilization. A century later, Rachel Carson surveyed that same landscape—first as a writer for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and later as the author of Silent Spring—and found it damaged. With Silent Spring, she almost singlehandedly launched the modern environmental movement. And that movement has as its objective the preservation of a natural order that Audubon took for granted. We will never get there, but Carson started us in the right direction. A good friend of mine who is a biologist once told me that our job is not to save the world, but to save ourselves. Audubon showed us why; Carson showed us how.

WR: What were the hardest parts of researching the lives of Rachel Carson and John James Audubon for publication, and how did your research methods differ in writing the two books?

WS: I’ve got a good answer, which sort of true, and a boring answer, which is totally true.

The good answer is that although biographical research is work, it is never hard if you’ve chosen your subject wisely. The test comes after the first year or two. Are you still intrigued? Do you still have the fever that set you off in the first place? I’ve been lucky (so far) that the answer has been yes. So the work is enjoyable and in no way “hard.”

The boring answer is that the hard part is organizing the material. How do you keep track of everything? There are ways, things you learn from others and things you invent for yourself. For Rachel Carson, I ended up with 100 pages of single-spaced notes and more than 3,000 documents on microfilm, plus a medium-sized library of books. Knowing where to find the one fact that you need from somewhere in all of that is the art of biography. Being clever helps, but sometimes it’s a matter of brute force. I can keep track of an amazing amount of stuff in my head.

You asked only about the research, not the writing. Now the writing—that is hard. I love it, but it is difficult. I had an editor once who liked to say that good writing is simple—but not easy. So true. Good writing involves several processes, but the most important is taking out the words that don’t belong. John Steinbeck knew this. In a well-known letter to his son Thom he apologized for going on for 18 pages. “I’d have written you a note,” he said, “but I didn’t have time.”

WR: John Steinbeck comes into your Rachel Carson book because of Ed Ricketts. How did Ricketts’s story contribute to your understanding of Rachel Carson?

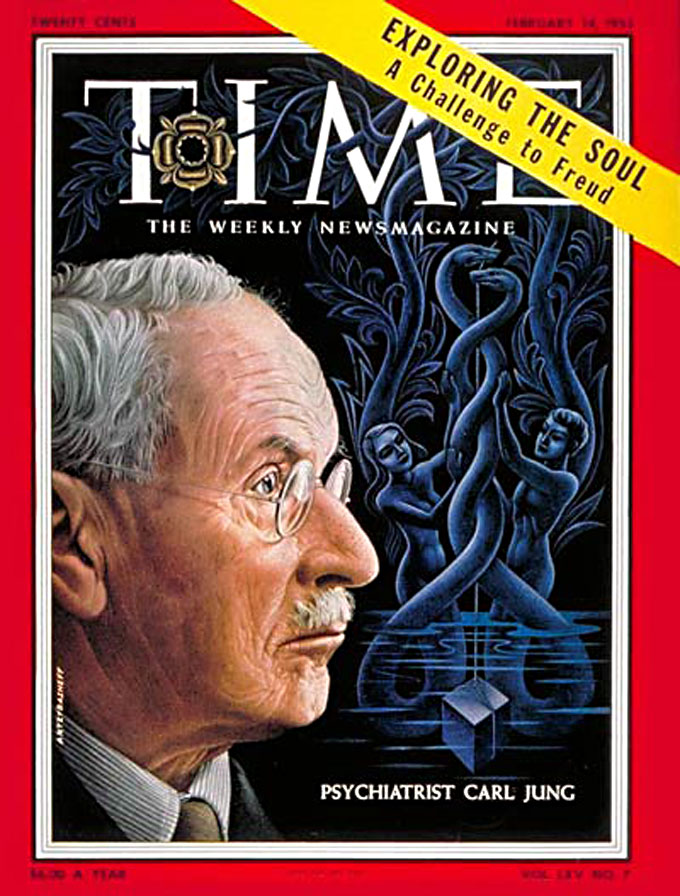

WS: Ricketts and Carson were opposites—except in the way they looked at the ecology of the seashore. Ricketts invented himself, devised a personal philosophy that corresponded to his bohemian tastes and voracious appetites. Ricketts devoured life. Carson was the product of university training and the studious contemplation of scientific research. She lived quietly with her mother and a couple of cats. Both Ricketts and Carson died young. Carson succumbed to cancer. Ricketts was run over by a train. Had the two of them ever met face-to-face I think it might have opened a worm-hole in the universe. But they agreed utterly on the nature of the world they inhabited so differently. Each understood that every living creature is part of an ecosystem that is maintained collectively by every entity within. When Carson began work on The Edge of the Sea, which had started out as only a guidebook for beachcombers, she consciously modeled it on Ricketts’s Between Pacific Tides

WR: When did you decide to write a new John Steinbeck biography, and why?

WS: I didn’t find Steinbeck. He found me. And, as you suggest, it happened when I was researching Ed Ricketts for the Carson book, especially the collecting trip Ricketts and Steinbeck undertook to the Sea of Cortez.

This is how it begins: You come across a name you know a few things about—he was from California, he wrote The Grapes of Wrath—and you get curious. And because you’re always on the lookout for your next subject you are always trying to fit the pieces of someone’s life into a narrative. And in Steinbeck’s case it was easy. His story cuts right across the headlong march of 20th century American history, which I find fascinating. Steinbeck is born just after the close of the Victorian era—and he dies a few months before Neil Armstrong steps onto the moon. So that was his material. I was hooked.

WR: What other similarities, differences, or patterns attracted you to Audubon, Carson, and Steinbeck as subjects?

WS: Writers and artists don’t have to be writers and artists. But they feel compelled. It’s in the nature of a calling, a feeling that you’re meant to do something particular with your time on earth. I don’t mean that in any religious sense. No greater being taps you on the shoulder and makes you understand that you should write East of Eden. It’s more like you can’t help yourself. I think that’s the common trait among Audubon, Carson, and Steinbeck. They couldn’t help themselves. They became stories worth telling.

WR: How does researching Steinbeck’s life differ from your research on Carson and Audubon?

WS: I don’t know yet. There will be many similarities. All three were prolific correspondents, and letters are a biographer’s most important resource. I guess the main difference will be contextual, in exploring the history more closely with Steinbeck. I know what I want to get into my book. It’s a specific feeling that is hard to describe. There is a government retreat in Shepherdstown, West Virginia called the National Conservation Training Center. It belongs to the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, Rachel Carson’s old outfit. It’s a beautiful campus in the rolling hills not too far from Harper’s Ferry. All of the buildings are lined with big, black-and-white photos, many from the agency’s glory days in the 1940s and 50s, of FWS personnel in the field. I’ve visited this place twice, and both times those photos got to me—elicited an ache. Like I could feel a connection to something that happened decades ago that would have been a great story to be part of. That’s the feeling you strive for in biography, the feeling that you are close to an earlier time, a different place, a person who lived in that time and place.

When I was in Scotland working on Audubon, I noticed that the library at the University of Edinburgh had a map room. I asked them if they had a map of the city from 1826, the year Audubon was there. And they did—a postal carrier’s map that was small and portable. I had them make a photocopy—I’d never been to Edinburgh—and then used that map to navigate around the city while I was there. And because Edinburgh is old, the map was still quite accurate. It helped me to see the city as Audubon saw it—to feel closer to my subject. One fog-bound night as I walked back to my hotel along one of the ancient cobbled streets I heard footsteps approaching and for a minute I let myself think it might be him.

WR: What is your research plan for the John Steinbeck biography, and how can readers of SteinbeckNow.com help?

WS: I’m just starting. There are important collections at Stanford, San Jose State, and in Salinas, as well as other places. And there are many Steinbeck experts and scholars I hope to talk with, and places he lived or that were important to him that I plan to visit. I expect to spend most of the next two years on research, and will write the book the year after that. It’s due to the publisher in the spring of 2018 and will be out sometime in 2019.

I’m happy to hear from anyone in the far-flung Steinbeck community with tips or leads about things I need to know.