A Story of Betrayal in John Steinbeck’s Time

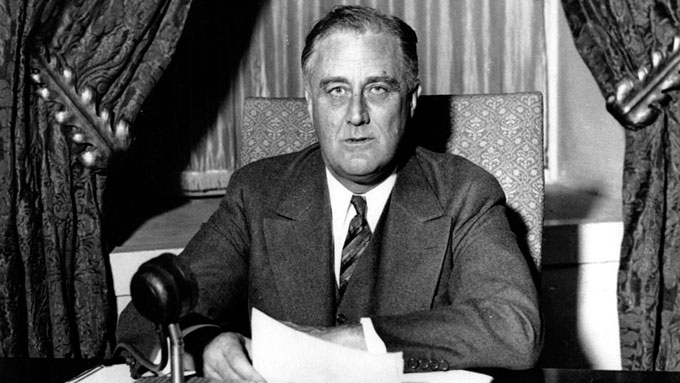

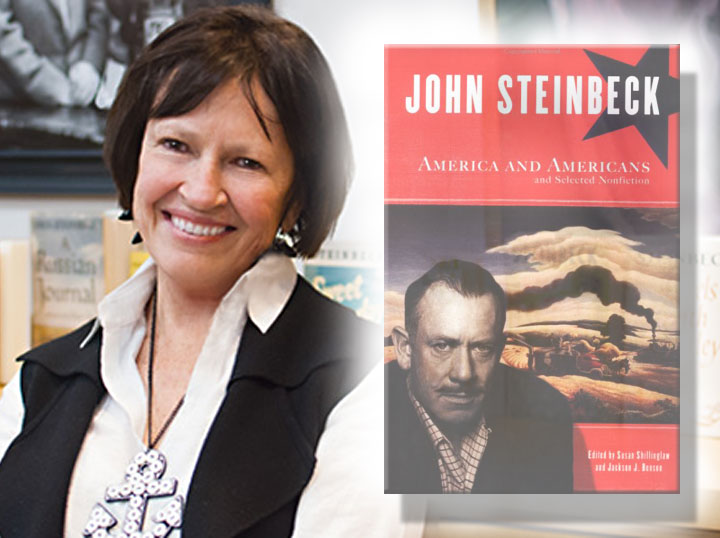

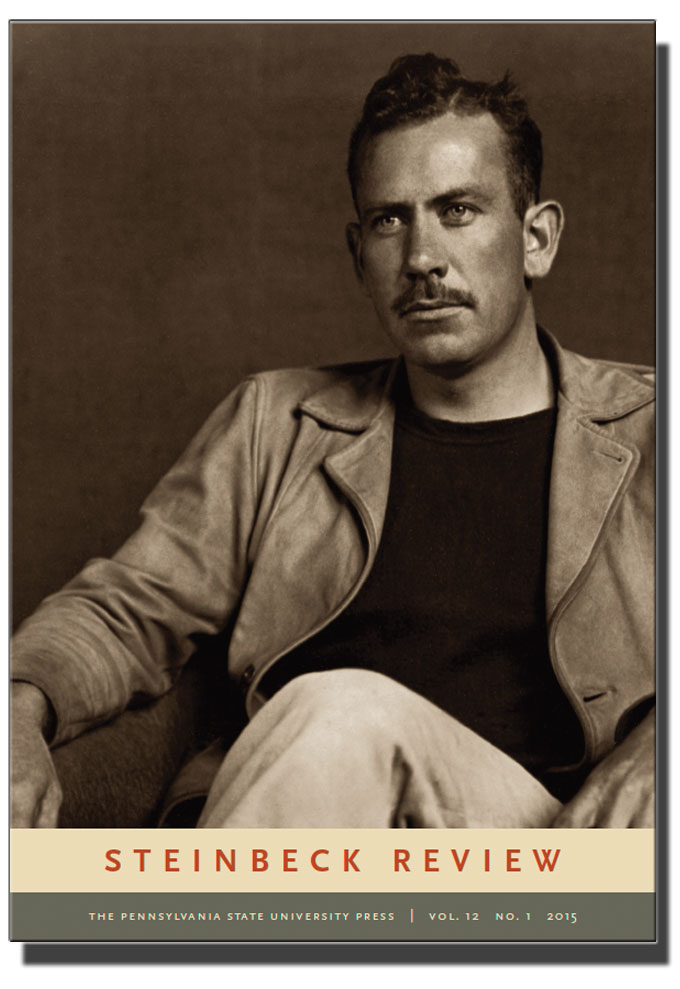

Winston Churchill’s mug? Odd connections to John Steinbeck’s life continue to appear at SteinbeckNow.com, thanks to authors like John Bell Smithback, a Far East expert and former resident of the neighborhood in Pacific Grove, California, where Sea of Cortez was written in 1941. His true story of the spy who contributed to the attack on Pearl Harbor—the 200th post since SteinbeckNow.com started—combines compelling narrative, imaginative investigation, and a streak of ornery independence, features that appeal to our readers and attract web surfers to John Steinbeck. Who knew that Winston Churchill colluded, through his silence, with a high-ranking Scottish spy to provide Franklin Roosevelt a reason to join Britain’s war with Germany? The true story begins in the spring of 1941, as Steinbeck sat writing Sea of Cortez while his marriage collapsed, Europe fell, and Japanese aggression threatened the Far East. On December 7, within days of the book’s publication, Japan attacked America at Pearl Harbor and Franklin Roosevelt declared war, as Winston Churchill had every reason to hope. Pearl Harbor swamped Sea of Cortez, which as John Steinbeck predicted it would, sold poorly. Blackballed from receiving a military commission by brass in Franklin Roosevelt’s war office, Steinbeck—remarried and living in New York in 1943—enlisted as a foreign war correspondent for American newspapers, reporting first from England, then from North Africa and Italy. In London he got leads and told stories other reporters overlooked. Did he hear rumors of a high-ranking spy in Winston Churchill’s government? “Certain people could not be criticized or even questioned,” he wrote years later in Once There Was a War, a collection of his World War II correspondence: “It is in the things not mentioned that the untruth lies.”—Ed.

Watching Churchill’s Funeral: An Incident in Pacific Grove

“Ambition, not so much for vulgar ends, but for fame, glints in every mind.”

Winston Churchill, The Second World War

John Steinbeck lived just around the corner. He was on Eardley Avenue and I was on Laurel. Of course, we lived there at different times—so different, in fact, that it might be said we inhabited Pacific Grove in different eras. When John was there in the spring of 1941, he and Ed Ricketts were working on Sea of Cortez and World War II was underway. Most of Europe was occupied by German forces, and Hitler had begun his invasion of the Soviet Union. General Rommel’s Desert Afrika Korps had taken Benghazi, President Franklin Roosevelt announced that he’d run for a third term, and the Japanese looked more and more menacing in the Far East. Glenn Miller’s Chattanooga Choo Choo would be playing on John Steinbeck’s radio, and Cheerios had just been invented.

During my time in Pacific Grove, Lyndon B. Johnson was President, Martin Luther King was leading the march from Selma to Montgomery, Dr. Benjamin Spock, Norman Mailer, and Norman Thomas were holding a teach-in in Berkeley to protest Johnson’s war in Vietnam, and a publication put out by the John Birch Society claimed that Negroes in America were better off than ever because of the good will of whites. The Byrds were singing Mr. Tambourine Man and television had replaced radio.

It’s January 30, 1965, and outside my door I notice a small woman moving back and forth with uncertainty. She studies my house, bends forward to read my address, then moves on. I turn on my television and find there is wall-to-wall coverage of Winston Churchill’s funeral. A barge with his coffin is moving slowly up the Thames past Tower Bridge, and the event is being described as one of the most moving tributes in modern history.

John Steinbeck lived just around the corner. He was on Eardley Avenue and I was on Laurel.

It’s at that moment that my doorbell rings and I open the door to find a frail and bewildered woman standing there. She’s the same one I’d seen earlier, and she says she’s visiting from England. She’s lost, she exclaims, and says she can’t seem to find her family’s house. I ask the address and assure her the house she’s looking for is nearby, just around the corner and down the block. She’s obviously exhausted so I open the door and invite her in, offering her a cup of tea and a chance to rest. “Winston Churchill’s funeral is on television, live and direct from London,” I say. “Come in and watch, and then I’ll drive you home.”

She stiffens and makes a disagreeable face. “Young man,” she scowls, “those of us who lived through the horrible days of the war owe everything to that great man. We stood alone, and his speech about fighting the Germans on the beaches strengthened us and led us through those terrible times. Even now, I can remember listening to his words on the wireless, and no thank you, I will not come in. I wouldn’t think of watching Sir Winston Churchill’s funeral on American television!”

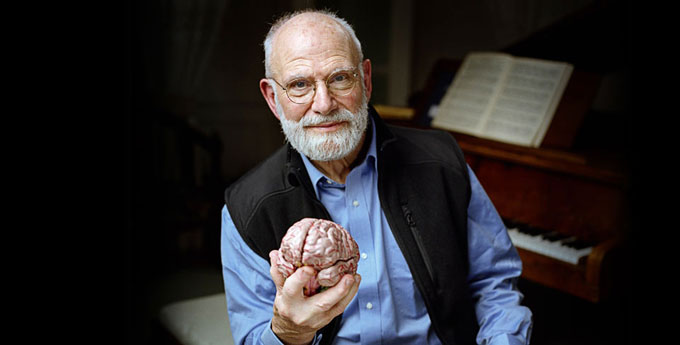

Such determination. And such a mistake. The truth is that few of Churchill’s speeches were broadcast during World War II: they were spoken in the House of Commons at Westminster to members of Parliament. Only after the war—in some cases, nine years after it—sensing the historical, political, and financial gains to be had, did Churchill record them in a studio for posterity. It wasn’t the first time the public had been duped into believing what Winston Churchill wanted history to believe. A true-story timeline of his long career would be made up of an unbroken series of serious errors, horrendous blunders, and Machiavellian maneuvers made to cover his many mistakes and further his vast ambitions.

Churchill the Manipulator, Wrong About Almost Everything

Several years ago the late Christopher Hitchens wrote a revisionist version of Churchillian history for The Atlantic magazine, describing Winston Churchill as “ruthless, boorish, manipulative, alcoholic, myopic, and wrong about almost everything” and noting that Churchill himself admitted he “never stood so high upon a principle that he could not lower it to suit the circumstances.” And lower it he did. So far, in fact, that had anyone else been Prime Minister when World War II ended, Winston Churchill—a Tory turned out of office by a Labor Party sweep—would in all likelihood have been arrested and tried for high treason.

Churchill was a master manipulator—ignoring the truth, bungling the facts, and rearranging historical events to enhance his deeply flawed role in a political career spanning nearly half a century. In his Atlantic article, Hitchens short-listed the worst mistakes, misdeeds, and deceptions and explained Churchill’s method: “A sort of alternate bookkeeping was undertaken, whereby the huge deficits of his grand story (Gallipoli, the calamitous return to the gold standard, his ruling-class thuggery against the labor movement, his diehard imperialism over India, and his pre-war sympathy for fascism) were kept in a separate column that was sharply ruled off from ‘The Valiant Years.'”

While the calculatedly slow release of official papers of the British government has helped Hitchens write Winston Churchill down, neither Hitchens nor anyone else to my knowledge exposed two acts of calculated treachery that facilitated Japanese imperial aggressions in the Far East, a deceit designed to drag the United States into World War II and give Franklin Roosevelt the justification needed to overcome domestic resistance. The first involved a Scottish lord, the second a slow-moving steamship.

Churchill’s Spy, At Work For Japan

The Scotsman was a hereditary member of the British House of Lords named William Forbes-Sempill, the 19th Baronet of Craigievar. A decorated Royal Flying Corps pilot in World War I, Sempill transferred to the Royal Navy Air Service when World War I ended in 1918. In 1921, the Imperial Japanese Navy requested England’s help in setting up its nascent naval air service. In the hope of negotiating a number of lucrative arms deals, the British Admiralty appointed Sempill to lead the government’s advisory delegation to Tokyo.

When he left for Japan, Sempill took with him the plans for two new British aircraft carriers, the HMS Argus and the HMS Hermes. Once he arrived, he proceeded to persuade the Japanese of the advantage of basing naval warplanes on ocean-going carriers instead of on airfields. Sempill was so pleased with his success in convincing the Japanese that he remained in Japan for 18 months, training pilots in techniques of flight control and shallow-water torpedo bombing—skills that 20 years later the Japanese Empire was to employ to disastrous advantage in attacking the United States fleet at Pearl Harbor.

Acknowledging Sempill’s “epoch-making service” to the Empire, Prime Minister Tomosaburo Kato awarded the Scottish lord Japan’s highest honor, the Order of the Rising Sun, “for his especially meritorious military service.” Sempill faithfully returned the favor: for the next two decades he was paid to provide the Japanese with secret information on the latest British aviation technology, helping Japan become a world-class naval power. It was only when Franklin Roosevelt’s administration raised concern over Japan’s growing naval strength that the British government questioned Sempill about leaking secrets to Tokyo. A resulting investigation revealed that Sempill was an active member of several far-right, anti-Semitic organizations in England, including the fascistic Anglo-German Fellowship, a secretive group dedicated to ridding the Tory Party of Jews.

The House of Windsor’s High Hopes for Germany

But Sempill wasn’t the only member of England’s establishment elite who embraced fascist ideology. The most famous—Sir Oswald Mosley, the 6th Baronet of Ascoats—founded the British Union of Fascists, and its activities received positive press from London’s Daily Mirror newspaper owned by the billionaire Lord Rothsmere, a Viscount. As Hitler rose to power in Germany, Mosley’s organization attracted dozens of viscounts and dukes, earls and barons, and a wide assortment of Lords and Ladies of the realm who were sympathetic to fascism and opposed to the rising Labor Party.

Even the Royal House of Windsor—formerly the German House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha—contained ardent supporters of Hitler’s cause. Until being forced to renounce his throne “for the woman I love,” Edward VIII, later Duke of Windsor, maintained such friendly relations with the Nazis that Albert Speer, Hitler’s arms minister, lamented his abdication: “I am certain that through him, permanent friendly relations could have been achieved. If he had stayed, everything would have been different. His abdication was a severe loss.” Two years after the outbreak of World War II, the disgraced Duke of Windsor and his American wife were living in neutral Portugal, where they met with Hitler’s representatives to negotiate a Nazi-sponsored return to the British throne. The twice-divorced Duchess stated that she would become Queen of England “at any price.”

Sempill wasn’t the only member of England’s establishment elite who embraced fascist ideology.

In Britain, the appeasement policy of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had been quietly encouraged by members of the House of Windsor who feared Britain’s involvement in the war would spell the loss of the British colonial empire. When the Duke of Windsor’s brother became King George VI, his Queen was heard to say she’d be happy enough if the Nazis invaded—”as long as they kept the royal family.”

For a time, neighboring Norway (the unnamed nation in John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down) entertained hopes that an arrangement with Hitler to remain neutral would keep the Nazis at bay and the monarchy intact. But when Norwegian royalty and the entire Norwegian cabinet suddenly showed up on England’s shores as refugees, barely escaping the Nazi occupation, Neville Chamberlain finally submitted his resignation to Buckingham Palace. The date was May 10, 1940, and at the pleasure of the King on England, the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Spencer Churchill was instated as Prime Minister.

Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt’s Fateful Atlantic Meeting

As Winston Churchill prepared to move into No. 10 Downing Street, he was handed a document from the war government’s new Bletchley Park Code and Deciphering Unit. The report showed that Sempill was still receiving payments, funneled through the Mitsubishi Corporation, to spy for the government of Japan from his position in the Admiralty office. For reasons of his own, Churchill chose to ignore the evidence and Sempill kept his post at Admiralty, where he continued to have unlimited access to sensitive information about military hardware and official secrets.

Though nearly all of the intelligence files on Sempill’s subsequent activities mysteriously disappeared, surviving records show that he traveled with Churchill to meet with Franklin Roosevelt at the Atlantic Conference, held in Newfoundland in August of 1941. Four months earlier, a Gallop Poll indicated that three-quarters of Americans would support joining England’s war, but only if they believed there was no other way to defeat Germany. Bolstered by the poll, Roosevelt sent his close friend and special adviser, Harry Hopkins, to deliver a private message to Winston Churchill in London: “The President is determined that we shall win this war together. Make no mistake about it: he has sent me here to tell you that at all costs and by all means he will carry you through.”

At the Atlantic Conference, however, Roosevelt reminded Churchill that the 1937 Neutrality Act enacted by Congress prevented direct intervention, and that the strong isolationist element in Washington still tied his hands. America First, a conservative anti-war movement formed after 1919, persuaded many citizens that enough American blood had already been shed in Europe, and the sentiment was shared by progressives within the President’s own party, many of them isolationists who expressed disappointment that Europe was “acting so tribal” and seemed unable to attend to its own affairs. A Republican Senator, Robert Taft, the son of a former President, spelled it out bluntly: “Even the collapse of England is to be preferred to the participation for the rest of our lives in European wars. If we enter the war today to save England, we will be involved in her wars the rest of our lives.”

Though details of what transpired at the Atlantic Conference remain cloudy at best, we know that two weeks before the meeting Franklin Roosevelt had closed the Panama Canal to Japanese traffic; and in retaliation for the Japanese occupation of French Indo-China, he ordered the seizure of Japanese assets in the United States. The governments of Britain and the Dutch East Indies quickly followed suit, with the result that, virtually overnight, Japan was deprived of 88 percent of its imported oil supply.

We also know Roosevelt again reminded Churchill that because of the Neutrality Act, the U.S. could only offer a token contribution to the British war effort.

“At least for now,” Roosevelt said.

“Unless,” Churchill asserted, “you are attacked.”

Roosevelt agreed: “Unless we are attacked first.”

And if that attack on America came from Japan? At Guam or Wake Island? Or in the Philippines, or even Pearl Harbor? Would the United States concentrate its forces in the Pacific rather than in Europe? In other words, when could England count on America’s attention?

Franklin Roosevelt, a New York patrician of Dutch-English descent, reassured Winston Churchill—the son of an American mother—that the United States was “with him all the way.” In the event of such an attack, America would throw her full weight behind Britain to defeat Germany and liberate Europe. Until then, fighting a war in the Pacific would be put on hold.

Churchill had cause to press his point: he knew that in a matter of months—even weeks—the United States would, somewhere in the Pacific, be attacked by Japan. Even Roosevelt knew something ominous was transpiring, for at that very moment all Japanese merchant vessels were being called home, presumably in preparation to transport troops and war material to points in the Far East targeted in Japan’s invasion plans.

But Churchill had other, more personal reasons for bringing Sempill to the meeting with Roosevelt. In the first instance, Sempill’s paymasters in Tokyo would learn that Roosevelt was giving them a considerable period of grace—as long as two or even three years—in which to solidify their gains. And secondly, Sempill’s boss, Winston Churchill, knew he would need a scapegoat for what was about to happen to Britain’s colonies in the Far East. It was, after all, a matter of political preservation, for at that point only he knew about the capture of the English steamship, the SS Automedon . . . .

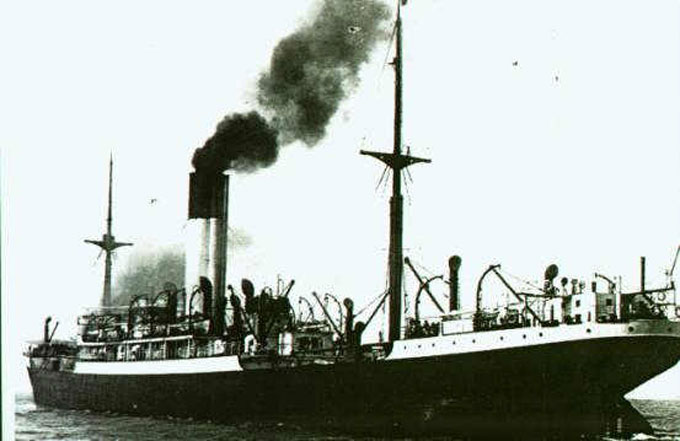

The SS Automedon: The Ship That Launched a Thousand Lies and Would Lead to the Death of Millions in the War

Within five days of the Atlantic Conference, Bletchley Park experts decoded a series of messages to Tokyo from the Japanese embassy in London containing nearly word for word the conversations that had occurred between Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill aboard the USS Augusta and the HMS Prince of Wales off the coast of Newfoundland. When Churchill read the transcript, he acknowledged it was “pretty accurate stuff,” then signaled for Sempill’s removal: “Clear him out while there is still time.”

Called before the Chief of Naval Air Services, Sempill received an ultimatum: quit or get sacked. Before Sempill could clear his desk, however, Churchill reversed his order to fire the spy. “I had not contemplated Lord Sempill being required to resign his commission,” he explained, “only that he be assigned elsewhere in the Admiralty.”

The story of the SS Automedon had yet to be disclosed. Best to keep a first-class spy like Sempill close at hand for a future bailout.

Best to keep a first-class spy like Sempill close at hand for a future bailout.

Outside John Steinbeck’s cottage beneath the oaks on Eardley Avenue, scrub jays call to one another in the trees, the California sun is warming the fragrant pines, and the monarch butterflies are making their annual pilgrimage to Pacific Grove. The writer has learned that The Grapes of Wrath has been awarded the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the controversial novel selling more than 430,000 copies, and Viking Press had ordered another printing. Steinbeck is spending his mornings working on a new book, one he and Ed Ricketts will call Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journey of Travel and Research.

But John Steinbeck doesn’t appear happy. There is a melancholy air about him as he makes manuscript corrections, sips a beer, and listens to Tommy Dorsey’s I’ll Never Smile Again on the radio. War clouds hover figuratively over his narrative of adventure and discovery, co-authored with Ricketts. Though Steinbeck’s wife Carol accompanied them on the expedition, he has just written her out of the book. Very soon he will write her out of his life.

John Steinbeck doesn’t appear happy. There is a melancholy air about him as he makes manuscript corrections.

Under a lead-colored sky in a more somber part of the world, a merchant ship flying the British ensign leaves the port of Liverpool bound for the tropical waters of Singapore. Hugging the coastline to avoid detection by German submarines, the slow-moving vessel eventually steams around the Horn of Africa into the relative safety of the Indian Ocean. Three days later, making its way east through calm seas, the SS Automedon is detected by a German military ship, the Atlantis—part of a fleet of surface raiders known as “ghost ships” that seek out and destroy merchant vessels carrying cargo to the Far East.

During a short encounter, the wireless operator aboard the Automedon has time to send a distress call that is picked up by two nearby merchant ships flying the British flag. They immediately send coded messages detailing the incident to naval listening stations in Singapore and Durban, South Africa. In turn, both stations relay word of the ship’s imminent capture to London. Overwhelming evidence indicates that British military authorities at the highest level are made fully aware of the Automedon’s fate.

At the scene of the encounter, a boarding party from the German ship finds the Automedon’s captain dead at the helm. A report filed by the leader, First Lieutenant Ulrich Mohr, states that “the ship proved to be unarmed and the crew gave up without a struggle. Unobstructed, we got to work on the strong room where we found fifteen bags of secret mail, including one hundredweight of decoding tables, fleet orders, gunnery instructions, and various British Naval Intelligence reports, including all the top-secret post en route for the Far Eastern Command, Singapore.”

Included in the haul is a complete set of Royal Navy fleet ciphers, New Merchant Navy ciphers scheduled to become valid in two months, a wealth of British Admiralty shipping and intelligence summaries, and several green bags containing 6,000,000 freshly minted New Straits Singapore dollars.

Lieutenant Mohr’s report continues: “Our search of the Chart Room brought us far greater rewards. Our real prize was a long narrow envelope enclosed in a green bag marked HIGHLY CONFIDENTIAL – SAFE HANDS – TO BE DESTROYED. It was addressed to the Commander in Chief, Far East, with the words TO BE OPENED PERSONALLY. It was equipped with brass eyelets to let water in to facilitate its sinking should it prove necessary to dispose of it at sea.”

Under a lead-colored sky in a more somber part of the world, a merchant ship flying the British ensign leaves the port of Liverpool.

The money, the reports, the codes, the intelligence reports, the green bags, the crew—the entire haul—was taken aboard the Atlantis. Then, stripped of its information and valuables, the Automedon is dispatched to the bottom of the Indian Ocean by German explosives. As the captain of the Atlantis sorts through the haul, he realizes that he’s looking at a mountain of intelligence information—a cache so vast, so significant, that he aborted his raiding mission and turned his ship to Truk Island, the nearest safe port in the Japanese-mandated island group.

There he transferred the secret documents and surviving crew of the Automedon onto a captured Norwegian tanker that was leaving for Kobe, Japan with 10,000 tons of aviation gasoline. As evening fell over Japan on December 5, 1940, the haul from the Automedon arrived at the German Embassy in Tokyo.

Over the next three days, Admiral Paul Wenneker, a German naval attaché, carefully photographs the codes and Chief of Staff reports taken from the Automedon before turning the haul over to a fellow officer, Captain Paul Karmenz, for delivery to Berlin. Karmenz went first to Vladivostok in Russia—for the moment a neutral nation—then crossed Russia by train, traveling day and night on his urgent mission.

If there was trouble, Admiral Wanneker planned to send a four-part coded telegram to Naval Command Headquarters in Berlin summarizing each of the captured reports. But the plan wouldn’t be needed. Safely delivered and deciphered, the messages were circulated among the Nazi top brass, and on December 12, under orders from Hitler, the Japanese naval attaché in Berlin was summoned to German Naval Command Headquarters. When he arrived, Captain Yokai was shown a copy of Wanneker’s summary which he immediately relayed to his superiors in Tokyo.

Yokai’s message to Tokyo was intercepted by an American listening station in the Pacific, probably on Guam or in Hawaii, where it was to sit in someone’s in-basket. It wasn’t to be deciphered until August 19, 1945, four days after Japan surrendered.

The German-Japanese Connection in the Wartime Far East

But in Tokyo, things were moving considerably faster. On December 12, Admiral Wanneker presented copies of the report to the Japanese Naval Chief of General Staff, Vice Admiral Kondo. The Admiral read the contents and shrugged. “These codes and position documents,” he remarked, “they have been allowed to fall into our hands to mislead both the Germans and the Japanese governments. This, of course, is a deception.”

“I doubt that emphatically,” replied Wanneker. “The Automedon was an unarmed merchant vessel whose captain was killed outright in our initial shelling. To a man, the crew surrendered without a fight, and upon boarding her First Lieutenant Mohr went directly to the captain’s quarters, where he found the sealed bags containing these documents. No, this is hardly a deception. The plain truth is that the ship’s encounter with the Atlantis was too short and swift to afford anyone an opportunity to destroy them.”

To make his point, Wanneker showed Kondo photographs of the green bag and a copy of the SAFE HANDS report that was to be handed over personally to the Far East Commander-in-Chief.

“This information is marked to the personal attention of Air Marshal Robert Brooke-Popham,” Wanneker adds, “And what we have here is an intimate view inside the British War Cabinet. These, Admiral, are the full minutes of the Cabinet’s meeting of 8 August 1940, a meeting in which a complete assessment of the Far East situation was presented. Included in it is a highly confidential Chief-of-Staff report on the defense of Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Far East with respect to their defenses against any Japanese attack.”

Kondo was silent, perhaps overwhelmed. “So,” he said slowly, clicking his heels sharply and bowing generously to Wanneker. “So, these are the minutes of the British War Cabinet, with their diplomatic and naval codes.” He whispered as if only half-believing his eyes and ears: “And, of course, full information on the defense of Hong Kong and Singapore.”

“Perhaps I can remind you, Admiral,” Wanneker said, giving weight to his words, “that it was Herr Hitler himself who directed that this information be shared with you.”

“Certainly, Admiral. I assure you that this material shall be given careful scrutiny. And you must extend Japan’s gratitude to your Führer,” replied Kendo, clicking his heels and making his exit.

The London Blitz and Japan’s Good Fortune

Three years earlier, Konto had been part of the military coalition that swept out the civilian cabinet in Tokyo and took control of the government, making Japan a military dictatorship much like Nazi Germany. Within five months, the coalition had put together a war plan and, on July 7, 1937—in the dead of night and without warning—Japanese troops launched an undeclared war against China.

As the coalition had surmised, the Chinese would be no match, and by 1940 Japan controlled every important city in China. There was only one exception, and that was the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong. Putting one boot across the border would, the invaders realized, incur the wrath and power of the British Empire. Instead, Japan turned its attention to nearby Siam (today’s Thailand), where by diplomacy and threat it established a large naval base and built a number of military airstrips.

Then, quite unexpectedly, on June 22, 1940 France surrendered to Germany and Nazi troops occupied Paris. Seizing the opportunity, Japan presented an audacious request to the collaborationist Vichy government: “As Germany’s ally, we demand that France relinquish immediate control of all its colonial possessions in French Indo-China.” When a positive reply was forthcoming, Japan’s military leaders made preparations to take over Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Putting one boot across the border would, the invaders realized, incur the wrath and power of the British Empire.

Back in England, Winston Churchill had just become Prime Minister, and as war raged across Europe, Japan’s expansionist policies began to encroach on Great Britain’s Far East possessions. Directing his War Cabinet to evaluate the situation with respect to Hong Kong, Malaya (Malaysia), and Singapore, Churchill wanted to know the size of the fleet that would be required to safeguard England’s Far East outposts in the event of war with Japan. Referring to a study made a year earlier, it was determined that the minimum needed to meet Japanese aggression would be a flotilla of 10 battleships and two battle cruisers, plus several cruisers and escort destroyers. It might even be necessary as well to send an aircraft carrier or two—an action requiring 70 days or more.

As if by chance, the German Luftwaffe chose that same moment to send 348 bombers and 617 fighter planes across the channel to bomb England. The first raid would last two hours, followed by a second, then by a third wave of bombers. They came by daylight, they came at night, and the bombing of England continued for 57 days. Homes vanished, factories were destroyed, cathedrals burned. Entire cities were devastated.

Back in England, Winston Churchill had just become Prime Minister.

In Berlin, Hitler issued Directive #16 setting in motion preparations for Operation Sea Lion, the Nazi plan for an event unprecedented since the Spanish Armada—a military invasion of the British Isles by sea. “As England still shows no signs of willingness to come to terms,” Hitler explained, “I have decided to prepare and, if necessary, to carry out a landing operation against her. The aim of this operation is to eliminate the English Motherland as a base from which the war against Germany can be continued.”

Meanwhile, urgent pleas were arriving in London from the Governors of Singapore and Hong Kong: “Where are the promised troops? Where are the promised ships? Where are the promised aeroplanes of the RAF?’’ The governments of Australia and New Zealand were asking the same questions.

In response, Winston Churchill convened his top advisers, ordering the British Chiefs of Staff to update their earlier estimates about the size of the fleet needed to protect Hong Kong and Singapore. The new report, 87 pages long, was gloomier than anyone could have imagined: Britain was in no position to resort to war if Japan attacked Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, or the Dutch East Indies. The Far East was indefensible, and without the active involvement of the United States, Britain’s remaining colonies were doomed. In the event of a Japanese attack, the Prime Minister was advised, Britain must make concessions and adapt a delaying strategy.

Churchill’s reaction was to dispatch a copy of the report to his newly-appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Far Eastern Command. It was a new command, making Air Marshal Robert Brooke-Popham responsible for all defense matters in Singapore, Malaya, Burma, and Hong Kong. In the interest of secrecy, Churchill’s decision was to hand the bag containing the full diplomatic report over to the captain of the S.S. Automedon for delivery.

Britain was in no position to resort to war if Japan attacked Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, or the Dutch East Indies.

Six thousand miles away in Tokyo, a military committee called the Council for the Conduct of the War poured over the intelligence report drawn up after careful review of the documents captured by the Germans from the Automedon. Captain Yamaguchi Bujiro (Head of 5th Intelligence Section, dealing with the U.SA.) and Captain Horiuchi Shigetada (Head of 8th Intelligence Section, dealing with Britain and India) offered this prediction to the Japanese General Staff: “Even if Japan sends forces into Indo-China or beyond, Britain will not go to war.”

The Council then sent the following message to Naval Marshal Admiral Yamamoto: “In the event it is decided to go to war in Southeast Asia, to neutralize the United States Pacific Fleet it is imperative that you begin drawing up plans to attack Pearl Harbor.”

On November 26, 1941, a Japanese attack force consisting of six aircraft carriers, nine destroyers, two battleships, two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and three submarines left Iturop Island in the Kurils northeast of Japan and began the 3,000-mile journey across the Pacific Ocean to its American target.

Before Pearl Harbor: The Great British Double-Cross

Within a week of the Atlantic Conference, a joint Army-Navy board in Washington had presented the results of an ongoing study to the White House: in the event of War Plan Orange (war with Japan), the Philippines could not be defended and would have to be yielded by default. The following day, Roosevelt signed a bill permitting the Army to keep men currently in service for an additional 18 months. Then, perhaps on a hunch, he ordered four of the seven aircraft carriers out of Pearl Harbor, along with a number of cruisers and destroyer escort vessels, three battleships, and 21 tenders, fuel ships, and minesweepers. The carriers left at Pearl Harbor were to be assigned missions away from Hawaii.

After Churchill’s meeting with Roosevelt, British ships loaded with Hurricane fighters en route to Singapore were abruptly ordered to change course. The planes promised to Singapore were dispatched to Libya instead. Experienced troops in Malaya and Singapore—the men best prepared to defend the Peninsula and save it from Japanese conquest—were put aboard ships and diverted to India, the Crown Jewel of the dissolving British Empire.

Churchill’s earlier authorization to send a fleet of fast torpedo boats to defend Singapore was similarly rescinded. In Hong Kong, Royal Air Force combat planes were ordered out and dispersed to Burma and India. Munitions and supplies from Canada meant for Hong Kong’s defense were inexplicably sidetracked to the Philippines, and the Bank of Hong Kong, which printed and controlled the colony’s currency, was spirited out of the colony. Additionally, every ranking government official in Hong Kong—from the Governor down to the Director of Public Works—was abruptly recalled to England or transferred to a safer location. Next, nearly all merchant and naval ships received orders to leave the harbors of Singapore and Hong Kong—immediately.

After Churchill’s meeting with Roosevelt, British ships loaded with Hurricane fighters en route to Singapore were abruptly ordered to change course.

Sometime between the hours of 2:30 and 3:00 the morning of December 7, at the very moment the fleet of merchant ships was hurrying out of Hong Kong harbor, Madame Sun Yet-Sen, widow of the Republic of China’s first president, plus the head of the London Times Newspaper Bureau and a number of other notables who had been visiting Hong Kong, were hurriedly piling their luggage outside their doors at the Hong Kong Hotel and desperately summoning help to get them and their luggage to a ship that was waiting in the harbor. When someone asked them why they were leaving in such a mad rush, they replied that he “had to be a dumb mutt not to know that the Japanese were going to attack Hong Kong at any moment.” Madame Sun Yet-Sen and the rest of the visitors got clean away; the “dumb mutt” didn’t. Like thousands upon thousands of others, he was to spend the next 3 years and 8 months being starved and beaten by Japanese guards behind barbed wire in a prisoner of war camp.

Clearly, the man behind the desk at No. 10 Downing Street knew not only what was about to happen in Hong Kong but when, and he was making last-minute adjustments.

Clearly, the man behind the desk at No. 10 Downing Street knew not only what was about to happen in Hong Kong but when, and he was making last-minute adjustments.

When the attack came, the defense of Hong Kong was left to a volunteer militia comprised of civilian businessmen, lawyers, merchants, bankers, and other professionals armed with pistols and World War I rifles. Canada, which had been asked to provide support troops, had responded by sending two battalions of fresh recruits–the Royal Rifles from Quebec and the Winnipeg Grenadiers—that had been training in the cool autumn climate of Newfoundland. Through a bureaucratic blunder, the young soldiers arrived in Hong Kong while their baggage and gear was sidetracked to Manila in the Philippines. They had disembarked in the tropical heat wearing their woolen winter uniforms, and nearly all of them were seasick. Three days later, the bombs fell. They were at war.

From London, Winston Churchill took to the airwaves to warn the military planners in Japan that, though under constant attack from the Germans, England had no intention of abandoning “one single centimeter of soil” in the Far East. As a consequence of its aggression, he said, Japan would have to reckon with the fearsome might of Great Britain. As proof, he said he’d already dispatched two of Britain’s newest, fastest, and virtually unsinkable battleships, the HMS Prince of Wales and the HMS Repulse, to the region.

On the third day of the war, the two major battleships were quickly and almost effortlessly sent to the bottom of the South China Sea by a squadron of Japanese torpedo bombers.

The Cost Of the War John Steinbeck Called Dishonest

In Pacific Grove, it would have been 10:55 a.m. on Sunday. Monarch butterflies clustered on the trunks of the pines, and from the shore came the sound of the surf rolling over rocks on the beach at the foot of Eardley Avenue. Gulls screeched, sea lions barked, and the noise of fishing boats returning from their morning sardine run came from Monterey Bay. In the distance, hawks soared in wide circles seeking thermals above Jack’s Peak, and as it was a day of rest, Cannery Row was silent. It was December 7, 1941, and Japan had gone on the attack. Across the Pacific, Asia was on fire and Pearl Harbor was burning. Though he couldn’t have known it, John Steinbeck would soon be leaving the scents and the sounds of Pacific Grove for a very long time.

To a shocked world, Pearl Harbor would be universally described as a surprise attack, and for the next 44 months America and the world would be at war. Thanks to a Scottish lord, Winston Churchill, and the easy capture of a slow-moving steamship, these are the territories that would be swiftly occupied by the Empire of the Rising Sun:

- Hong Kong

- British New Guinea

- The Philippines

- Guam

- Dutch East Indies

- Portuguese Timor

- Malaya

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Straits Settlements (Singapore)

- Kingdom of Sarawak

- Brunei

- North Borneo

- Nauru

- Imphal

- Wake Island

- Gilbert and Ellice Islands

- Christmas Islands

- Attu and Kiska Islands

One year after the capture of the Automedon, the crew of the Atlantis would be invited to the Emperor’s Palace in Tokyo where Captain Rogge would be presented with a samurai sword by Emperor Hirohito. Only two other Germans had received such an honor: Field Marshal Hermann Goering, and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the Desert Fox.

Franklin Roosevelt, the 32nd President of the United States, died while still in office, at Warm Springs, Georgia on April 12, 1945, age 63. The President from Hyde Park, New York was mourned by millions around the world.

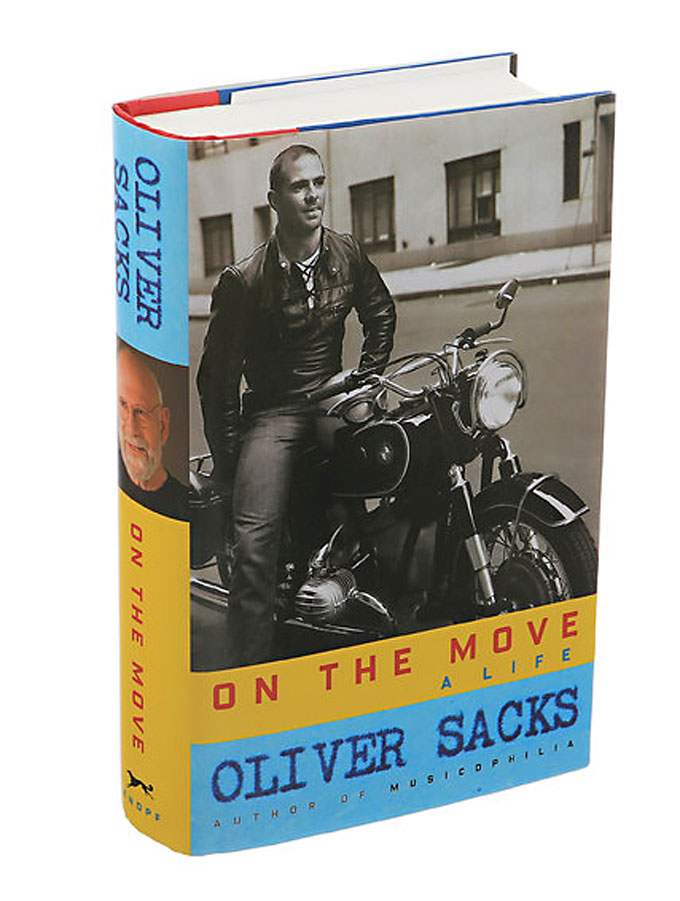

Sir Winston Churchill, KG, OM, CH, TD, DL, FRS, RA, lived 20 years longer, passing away peacefully in his own bed in London, age 90, on January 24, 1965. His state funeral would be described as the largest in the world. In Britain, the Secrets Act protects official papers from public scrutiny for a period of thirty years. Before leaving office, Churchill locked his official and personal papers out of public reach for a period of 50 years after his death.

Churchill carried the secrets about Sempill and the Automedon to his grave, but during the terrible days that Singapore and Hong Kong were under attack, he issued these words to their doomed defenders: “There must be no thought of sparing the troops or population; commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honor of the British Empire and the British Army is at stake.”

The man in Singapore to whom the order was addressed, Air Marshal Robert Brooke-Popham, was in such a hurry to flee the burning island in the final days of its siege that he broke a leg scurrying down a ramp to board the speedboat that would take him to the safety of Australia. It was he, the Far East Commander-in-Chief, to whom Winston Churchill had sent the TOP SECRET, HIGHLY CONFIDENTIAL documents. Via the SS Automedon.

Churchill carried the secrets about Sempill and the Automedon to his grave.

William Forbes-Sempill—19th Lord Sempill and Baronet of Craigevar, AFC, Third Class Commander in the Order of the Raising Sun (Japan)—died 11 months after the death of the Prime Minister who protected him, at his Craigevar Castle in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, at the age of 72. Ten days following the outbreak of war in the Pacific, at the moment Hong Kong was on the verge of surrendering, Sempill was discovered making calls to the Japanese Embassy in London. The Admiralty asked him to retire immediately, and that time he did. Unfortunately, his ruling-class connections saved him from the hangman’s noose.

Most of the documents relating to Sempill’s spying activities, like a great many of Winston Churchill’s papers, have disappeared from government archives, as have those relating to the SS Automedon. The depth of one man’s treachery, and the collaboration of another, only came to partial light in 2002. But the following statistics suggest the scale of destruction caused by this forgotten man of history, and by the Prime Minister who protected him.

Casualties in the Pacific War numbered approximately 36,000,000, half of the total casualties of the Second World War.

The estimated number of civilian victims of Japanese democide is 20,365,000:

- China—12,392,000

- Indochina—1,500,000

- Indonesia—375,000

- Dutch East Indies—3,000,000

- Malaya and Singapore—283,000

- Thailand—60,000

- Philippines—500,000

- Burma—170,000

- Pacific Islands—57,000

- Timor—60,000

The number of POW deaths in Japanese captivity is estimated at 539,000:

- Netherlands—8,500

- Britain—12,433

- Canada—273

- Philippines—23,000

- Australia—7,412

- New Zealand—31

- United States—12,935

Out of 60,000 Indian Army POWs taken at the Fall of Singapore, 12,000 died in captivity.

Not long after the war ended, John Steinbeck issued his own statement about the war that he had reported on from London, North Africa, and Italy: “The crap I wrote overseas had a profoundly nauseating effect on me. Among other unpleasant things, war is the most dishonest thing imaginable.” One wonders if, in the course of his foreign travels, he had discovered the true story of treachery and deceit recorded here.