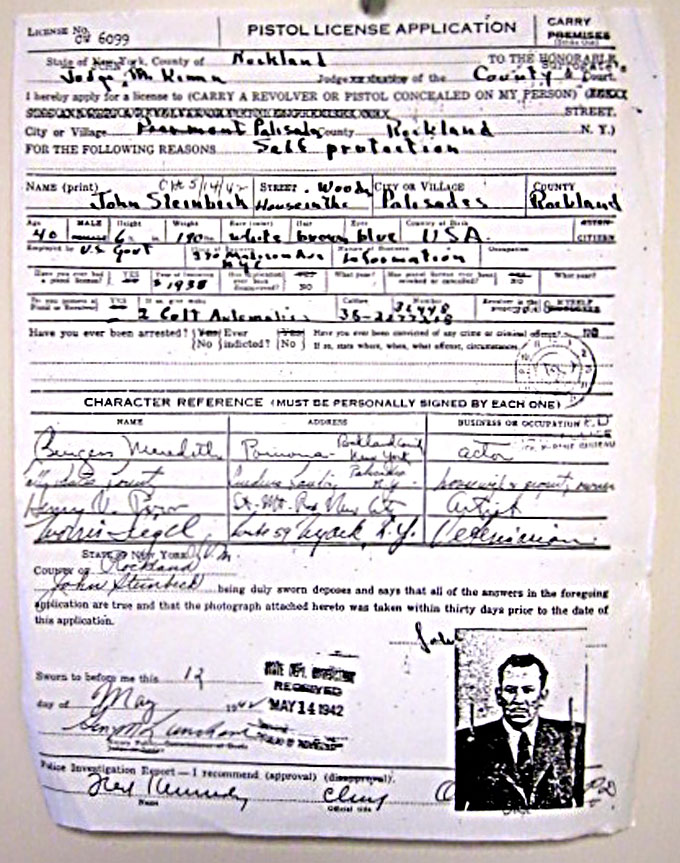

The historic visit to America by Pope Francis, which included the canonization of the Spanish-California missionary Junipero Serra, made some right-wing Catholics in Washington angry, though it would have pleased John Steinbeck, a politically progressive Episcopalian with Catholic sympathies. The pope’s call for justice, mercy, and kindness to strangers in his address to Congress inspired the editor in chief of Steinbeck Review to write about her experience with grace during a trip she took with her husband to a city John Steinbeck experienced as a welcome guest in times of war and peace: London, England.—Ed.

In “Republicans Could Have a Pope Problem,” a syndicated column about Pope Francis’s recent visit published in the September 25, 2015, Birmingham, Alabama News, the journalist Margaret Carlson writes, “Pope Francis suffused Washington with what Catholics would call grace and what everyone else—for the crowds aren’t just believers—would call pure, almost childlike happiness.” Concluding that “this is what goodness looks like,” she predicts that certain politicians and vested interests may find the Pope’s message to America—one that is so very much like John Steinbeck’s moral stance in The Grapes of Wrath—problematic, even meddling. Notes Carlson of the Pope’s emphasis on immigration reform, economic justice, and ecological awareness during his speech to Congress:

My God, he’s questioning unfettered capitalism and the worship of wealth. . . . “The son of an immigrant family” said we should welcome those who come to the U.S. Such effrontery. With Republicans watching from lawn chairs, he said that those at the top of the economic heap have a duty to fight climate change on behalf of the millions left behind by the global economic system. “Climate change is a problem which can no longer be left to a future generation,” he said. Before he leaves, he could very well call for raising taxes.

John Steinbeck would have loved this pope, who chose the occasion of his American visit to canonize Junipero Serra, the 18th century Franciscan missionary to Spanish California. Like Steinbeck, Pope Francis has a compassionate heart for the dispossessed, a dim view of ostentatious consumerism, and an abiding sense of our intimate connection to Mother Earth and the interrelatedness of all things that Casy proclaims in The Grapes of Wrath. Like Francis, John Steinbeck’s novel challenges the status quo, holds out hope for change despite the odds, and calls for love in a world threatened equally by the hatred of enemies and the complacency of friends and allies.

John Steinbeck would have loved this pope, who chose the occasion of his American visit to canonize Junipero Serra, the 18th century Franciscan missionary to Spanish California.

Although not a Catholic, California’s greatest writer was a political progressive who was friendly to Catholicism and saved his criticism of organized religion for the narrow-minded and the hypocritical—characteristics of conservative Catholic politicians such as Senator Marco Rubio, to whom Carlson refers in her article. “As for Rubio,” she suggests, “perhaps the Pope will persuade him to follow Christ’s teachings and not his most conservative followers and donors. Miracles do happen.”

Although not a Catholic, California’s greatest writer was a political progressive who was friendly to Catholicism and saved his criticism of organized religion for the narrow-minded and the hypocritical.

An Anglican who loved to travel, John Steinbeck particularly liked London, England, where I experienced my own minor miracle on the last leg of the European trip my husband Charlie and I took shortly before Pope Francis came to the United States. The date was September 20, the night before our return flight to Atlanta; the place, London’s Mayfair Millennial Hotel. As we finished dessert in the hotel dining room and prepared to pay our bill, my husband reached for his wallet. It wasn’t in his pocket. We knew instantly how someone had taken it earlier in the day—giving me a shove and stealing Charlie’s billfold while we were distracted. Far from home and facing the prospect of having to cancel all of our credit cards, we felt violated, desolate, and a bit desperate.

I experienced my own minor miracle on the last leg of the European trip my husband Charlie and I took shortly before Pope Francis came to the United States.

Thirty minutes before we were scheduled to check out the next morning, our concierge phoned our room with welcome news: “A lady has called to report that she has your billfold. It is being held for you at a hotel not too far away, and you may pick it up any time.” When we arrived at the hotel, we found Charlie’s wallet intact—his credit cards, his driver’s license, even his cash. Details of what happened to the billfold—it had been found by a Good Samaritan on a street far from Regent’s Park, where we had spent the previous afternoon—remained a mystery. As we left for the airport to fly home, everyone at the hotel desk was smiling, agreeing that this warmhearted act of grace was a “London miracle.”

As we left for the airport to fly home, everyone at the hotel desk was smiling, agreeing that this warmhearted act of grace was a ‘London miracle.’

The incident in England made an impact on us that John Steinbeck would have understood and appreciated. Like the presence of Pope Francis in the United States, it restored our belief in the possibility of goodness and honesty, decency and kindness. As Margaret Carlson notes, “Miracles do happen.”

The incident in England made an impact on us that John Steinbeck would have understood and appreciated.

Pope Francis is calling for miracles today, and characters in Steinbeck’s fiction like Ma Joad attest to their possibility. Perhaps we shall see more “miracles” in the future. I hope so, because our own fate and that of the earth we inhabit depend on them. Perhaps “good will,” “the common good,” and sustaining “Mother Earth” will become practical possibilities rather than impossible dreams. Perhaps the impression left by Pope Francis will endure, making life better for the planet we inhabit and for the strangers in our midst, whether on our border or on a side street in London, England.