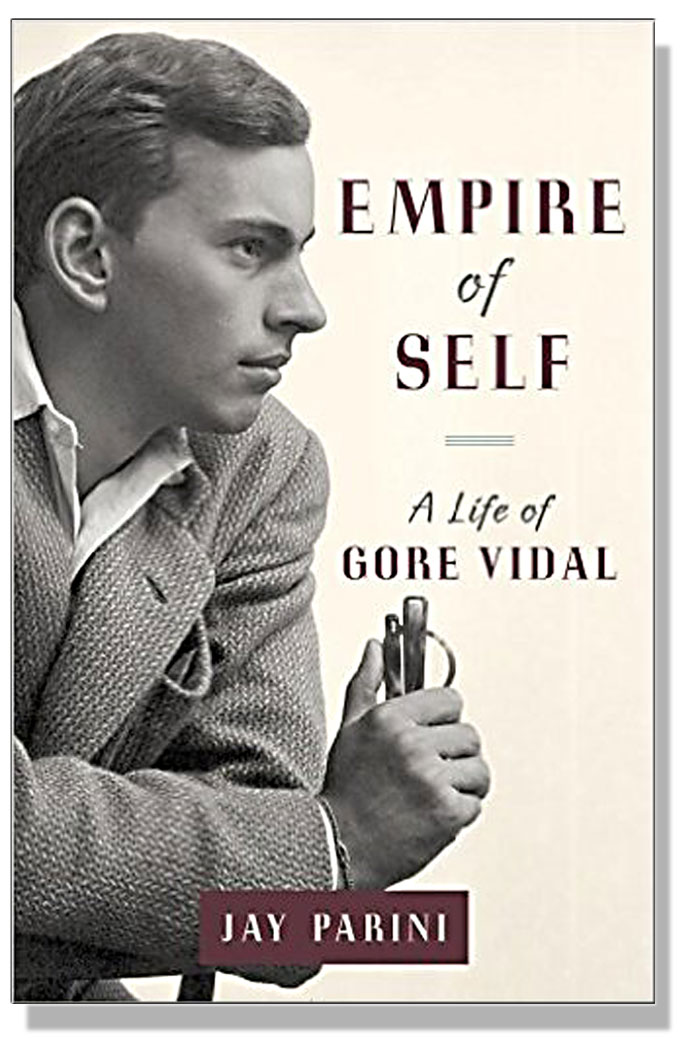

Though they were born a generation apart on opposite coasts, John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal—bestselling writers with close ties to Broadway, Hollywood, and progressive politics—had much in common. Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal, by John Steinbeck’s versatile biographer Jay Parini, considers the controversial author of Lincoln, Burr, and Myra Breckinridge to be a master of historical fiction, a literary form that didn’t fit Steinbeck but suited Vidal, who renewed its energy and spawned a generation of imitators. Axinn Professor of English at Middlebury College and a poet-novelist-critic who understands what creative writers endure for their craft, Parini suits Vidal particularly well as a biographer. Like John Steinbeck: A Life (1995), his life of Gore Vidal provides a contemporary writer’s perspective on a controversial literary career, with an advantage not shared by biographers of Steinbeck. Parini and Vidal were friends until Vidal’s death in 2012, and Parini had frequent conversations with his fascinating subject, who gave him free access to Vidal’s extraordinary circle of friends, associates, and yes, enemies.

Jay Parini, John Steinbeck, and the Case for Gore Vidal

The result of that fortunate relationship is a compelling chronicle—detailed in research, comprehensive in scope, and convincing in its case for Gore Vidal as a 20th century writer who, like John Steinbeck, is worth reading in the 21st. Describing himself as Vidal’s Boswell, Parini views his volatile subject with the empathy of a colleague and the wonder of a disciple, forgiving without judging, or ignoring, the master’s faults. This is an advisable stance for any biographer, but it serves Gore Vidal’s peculiar personality and expansive sense of self particularly well. John Steinbeck was a shy man with a domestic situation that made research and publication difficult for biographers following his death in 1968. Vidal, who admired Steinbeck and served as a source for Parini’s Steinbeck biography, avoided this danger by admonishing Parini to note the potholes but keep in his eye on the road when writing the biography that Vidal made Parini promise he would finish when Vidal was gone.

Parini views his subject with the empathy of a colleague and the wonder of a disciple, forgiving without judging, or ignoring, the master’s faults.

A gentle sort without Vidal’s sharp edges, Parini kept the bargain, filling in the self-narrative begun by Vidal in the novels Vidal wrote in his 20s, in essays and interviews and plays over a period of six decades, and in a pair of provocative memoirs that leave no prisoners. As suggested by the title Parini chose for his biography of this great-but-not-good man, Vidal’s story fascinates because it records the self-invention of a born storyteller who wrote prodigiously, characterized non-historical fiction like Myra Breckinridge as “inventions,” and considered bitchiness and versatility to be evidence of talent. He was as competitive with writers as we was in sex, and he fought publicly with colleagues who crossed or criticized him. He attacked Truman Capote, a soft enemy, and made scenes with Norman Mailer, a tougher target. He suggested that John Steinbeck, who avoided snits with other writers, was a bit of a one-note: “He “didn’t ‘invent’ things,” Vidal said of Steinbeck. “He ‘found’ them.”

Gore Vidal and John Steinbeck: Two Lives in Letters

Like Samuel Johnson, John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal were thin-skinned, temperamental men with mother issues. Both felt sorry for their fathers and identified with their fathers’ fathers, stronger figures, in their writing. Steinbeck compensated for self-doubt by avoiding public appearances and entangling private alliances beyond a loyal circle of friends, collaborators, and relatives. “Your only weapon,” he advised a young writer whose father was a boyhood friend, “is your work.” Vidal, a domineering narcissist, adopted the opposite strategy, creating a public persona built around conflict, desire, and adulation. Work was one weapon. So was a personality that, as Jay Parini observes, others could love or leave but never outrun. Steinbeck was a turtle. Vidal was a hare.

John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal were thin-skinned, temperamental men with mother issues. Steinbeck was a turtle. Vidal was a hare.

Reared in a rural California town where the Republican Party ruled and the Episcopal church was a center of social life, John Steinbeck got off to a slow start as a writer. Cup of Gold, his first novel, fails as historical fiction about a far-off time and place; an early attempt at mythic allegory, To a God Unknown, succeeds only because it is rooted in familiar soil. He finally found his voice in three novels, written during the Great Depression, about America’s rural underclass: ranch hands and farm workers in California, migrant sharecroppers from Oklahoma. He lived in small houses and wrote in small rooms and never forgot what it was like to go without; he feared success, and and he was right. A New Deal Democrat, he wrote political speeches but refused to make them. As with Gore Vidal, alcohol was a social lubricant, but to opposite effect. Vidal performed in company. Steinbeck looked and listened. Steinbeck liked working people, preferably farmers, and, like Faulkner, he lived part-time in the past. So did Vidal, of course, but his past was imagined rather than remembered.

Vidal performed in company. Steinbeck looked and listened. He liked working people, preferably farmers, and lived part-time in the past.

Vidal was born in Washington during the administration of Calvin Coolidge and spent his happiest times at the Rock Creek Park home of his blind grandfather T.P. Gore of Mississippi, elected U.S. Senator from Oklahoma when Oklahoma became a state. Vidal’s roots were Deep South (Al Gore is a distant relative), but his social centers as a boy were Capitol Hill, New York, and the mansions of his grandfather and his mother’s second husband, Hugh Auchincloss, a millionaire who later married the mother of Jackie Kennedy. Like Steinbeck, Vidal was christened as an Episcopalian, but he attended St. Albans, an exclusive academy run by the Episcopal Church, rather than public school. He fell in love with a classmate, and both enlisted at age 18. The boy he loved was killed in combat and, as Parini suggests, left a hole in Vidal’s heart that lasted for a lifetime.

Like Steinbeck, Vidal was christened as an Episcopalian, but he attended St. Albans, an exclusive academy run by the Episcopal Church, rather than public school.

He disliked his mother, liked his father’s girlfriends, and imbibed the Dixiecrat politics of his Grandfather Gore, which were to the right of the Steinbeck family’s progressive California Republicanism. Parini describes the anti-New Deal bias Senator Gore shared with Dixiecrat allies like Huey Long as “Tory populism”: anti-corporate, anti-war, and anti-statist, anti-values that defined Vidal’s vision of America as a Republic gone bad, like Rome, in his political essays, his historical fiction, and his campaigns for public office, first as candidate for Congress from New York, later for Governor of California. If Vidal read The Grapes of Wrath to Senator Gore as a teenager, a distinct possibility, the old man probably reacted like his fellow Oklahoman, Lyle Boren, who denounced Steinbeck’s depiction of Oklahoma from the floor of the U.S. House: with denial and disdain. Vidal’s view of America as a child was that of his grandfather’s political class: nativist, isolationist, and distrustful of Wilsonian-Rooseveltian democracy. His ambitions as an adult, like his homes on the Hudson and in Italy, were imperial.

Vidal’s view of America as a child was nativist, isolationist, and distrustful of democracy. His ambitions as an adult, like his homes on the Hudson and in Italy, were imperial.

Parini records the first time Steinbeck and Vidal met, on May 8, 1955, at a Manhattan party given by the producer Martin Manulis following the TV broadcast of Visit to a Small Planet, Vidal’s satirical comedy about Cold War paranoia and gone-mad McCarthyism. Vidal’s sci-fi caricature of mid-America invaded by aliens eventually ran on Broadway and has since been revived. When Vidal met Steinbeck at the Manulis party, Steinbeck would have been involved in staging Pipe Dream, the musical adaptation of Steinbeck’s novel Sweet Thursday by Rodgers and Hammerstein that closed within months after opening later in 1955. Steinbeck’s wife Elaine, also present at the party, was a stage manager for the 1940s hit musical Oklahoma! and had a good eye. She remembered the 30-year-old Vidal as “a tense, smart, glittering young man” who shared Steinbeck’s “passion for politics” and got along with her husband. The two men shared a special affection for Eleanor Roosevelt and an admiration for Adlai Stevenson, neither of which would have appealed to their families back home.

Steinbeck and Vidal shared a special affection for Eleanor Roosevelt and an admiration for Adlai Stevenson, neither of which would have appealed to their families back home.

Vidal also felt an affinity for Steinbeck as an artist, noting to Parini that both authors had the ability to write narrative and dramatic works that people liked. Vidal said he envied Steinbeck’s “happy relation to Hollywood,” where Steinbeck’s work “adapted well” and “was treated with respect,” unlike his own. He observed, accurately, that the film East of Eden “brought Steinbeck to more people’s attention than a novel could have ever done.” And though both writers feared that television “spelled the end of the novel,” their most popular works in novel form have also proved to be their most enduring: The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, Cannery Row, and East of Eden for Steinbeck; Burr, Lincoln, and other historical fiction of American Empire for Vidal. Of the book critics who were irritated by Steinbeck’s persistent popularity, Vidal observed, “they could never forgive Steinbeck for saying things that people wanted, or needed, to hear.” As Empire of Self shows, the same can be said of Gore Vidal.

I love this: “Reared in a rural California town where the Republican Party ruled and the Episcopal church was a center of social life, John Steinbeck got off to a slow start as a writer.” I had not thought of Steinbeck’s beginnings in this way before now.

The review is rife with such brilliance. You take us to school in just the right way, Will.

Coming from a creative writer of your versatility and experience, this means a lot, Roy. As I note in the review, one reason Jay Parini’s biographies of Steinbeck, Faulkner, Frost, and Vidal are worth reading is that he’s a widely published creative writer, too. Thank you for your comment.

Fantastic review, Will. I’m a great admirer of Parini’s work (creative as well as scholarly) and look forward to reading his take on Vidal. I’m especially interested to know why Vidal, to borrow your phrase, “considered bitchiness and versatility to be evidence of talent.” Versatility okay, but bitchiness?

On another note, I wanted to say how fascinating it has been to read the articles on this site about people and topics other than Steinbeck. Here, Steinbeck functions as a kind of benchmark or scientific control against which everything else is compared. In the case of Gore Vidal the comparison is perfectly apt because they were contemporaries, co-laborers in the literary arts, and even cocktail party acquaintances, but I would argue that an exercise like this would be just as rewarding if we were to consider a non-contemporary like Steve Jobs, Hillary Clinton, or Jonathan Franzen.

You’re right on each point you make in your thoughtful comment here, Nick. ‘Bitchiness’ may be too strong, but Vidal exemplified and practiced this unpleasant trait in his relations with friends, enemies, and colleagues alike, as Jay dramatically demonstrates in his observations and interactions with Vidal over a period of 25 years. Though Vidal’s Empire of Self required compliant courtiers, he tolerated energetic willfulness, playful and otherwise, in artists he considered his equal, such as Fellini. (Parini is pitch-perfect on this particular subject.). As an author with experience in film writing, you’re in for a great read–and a number of eureka! moments of your own.

No one would enjoy reading about character comparisons and imaginary conversations between Steinbeck and Jobs, Clinton, or Franzen more than I would. Please pick one and write the piece. I promise top-of-page placement and lively response.

Very well done, Will, and very enlightening. I love Gore Vidal, and his statement that “Steinbeck did not invent things, he found them” is so insightful. Essentially that is one of the ideas that I learned from Steinbeck which contributed to forming my Discovery Process and Social Ecology theory. To stay grounded, stay real, and work within a culture you have to find things in people’s real-life experiences that you can relate to. Steinbeck was a master at this. When one finds things or discovers them first-hand there is a reality that is unrelenting in moving towards the outcome Vidal expressed in his statement,“they (his critics) could never forgive Steinbeck for saying things that people wanted, or needed, to hear.”

Someone once asked Steinbeck how he did his work. His response was clear and simple: “‘The process is this–one puts down endless observations, questions and remarks. The number grows and grows. Eventually they all seem headed in one direction and then they whirl like sparks out of a bonfire. And then one day they seem to mean something.” I love that quote.

Steinbeck must have loved Abraham Lincoln, who believed in the people as he did. A quote from Lincoln’s debate with Stephen Douglas in 1857 says it all: “In this and like communities, public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently he who molds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions. He (the citizen) makes statutes and decisions possible or impossible to be executed.” Steinbeck certainly “molded public sentiment.”

Then you’re in for a treat when you read Gore Vidal’s biographical novel about Lincoln, perhaps his masterpiece in a genre that, as Jay Parini points out in the concluding chapter, Vidal renewed.