Good news from Down Under. A Thousand Shards of Glass, a collection of essays, letters, and journal entries by the travel writer-photographer Michael Katakis, has been published in paperback and eBook by The Author People, an Australian outfit with a pioneering approach to book publishing. Founded in 2015 by Lou Johnson and Tom Galletta, the firm is dedicated to connecting authors with their audiences, wherever they may be around the world.

The most recent collection of essays, letters, and journal entries by the travel writer-photographer Michael Katakis has been published in paperback and eBook by The Author People, an Australian outfit with a pioneering approach to book publishing.

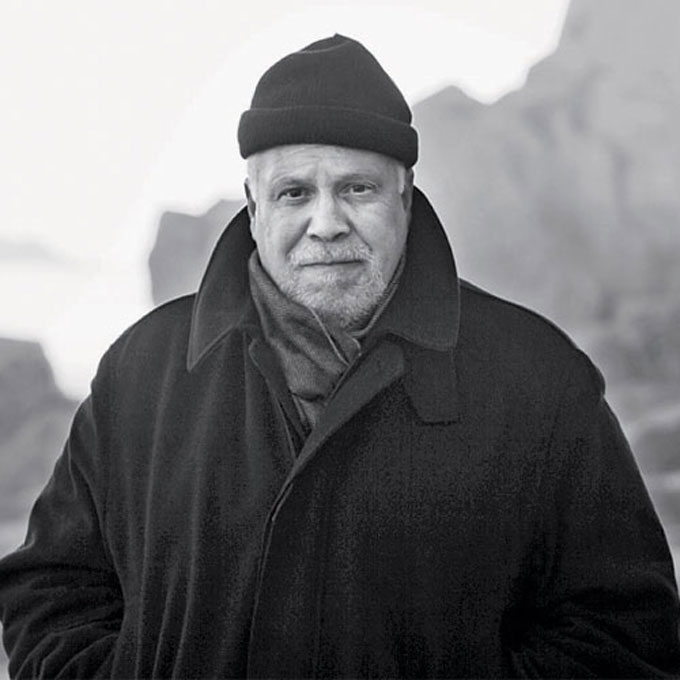

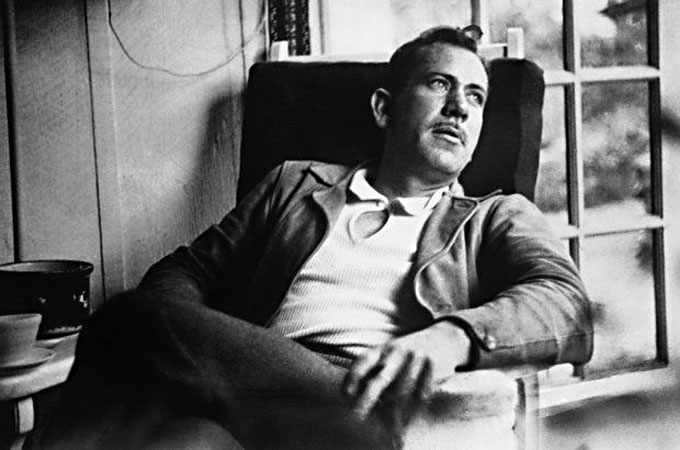

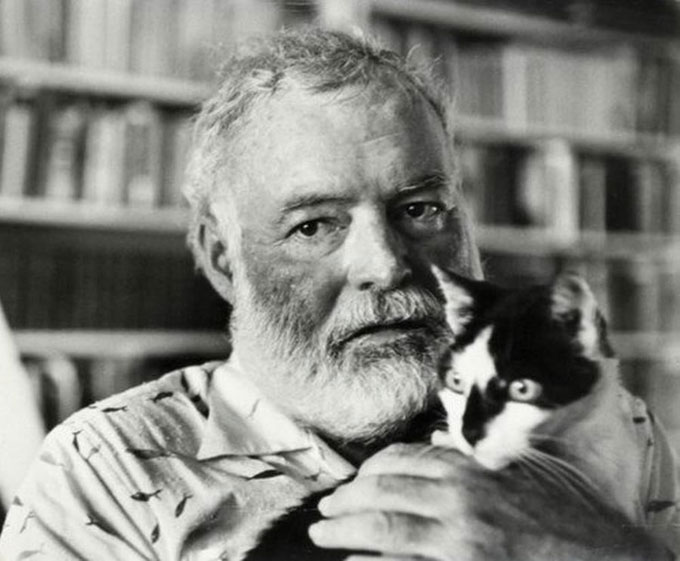

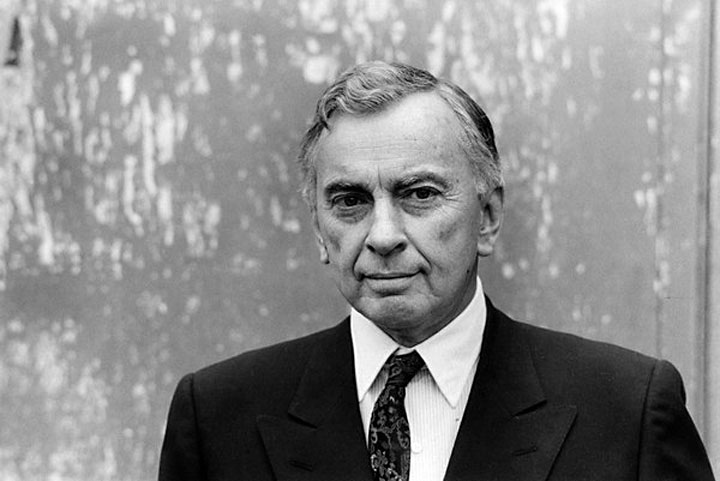

I first read A Thousand Shards of Glass in 2014, the year Simon & Schuster released a hardback edition of the book in Australia and the United Kingdom while ignoring its intended market—the United States. Since then, I’ve met Michael Katakis in Carmel, California, his part-time home, and I admire his perceptiveness as a thinker, writer, and photographer. Like John Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway, he’s an American author with a distinctive point of view, writing for a country described by Gore Vidal as “the United States of Amnesia.”

Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Vidal come up frequently in conversation with Katakis, an imposing figure with a similar intensity. In his talk, as in his career, his range of knowledge and engagement is impressive. He’s the manager of Hemingway’s literary estate, and an expert on the author. He knows much (but, diplomatically, says little) about Carmel, California, a place Steinbeck once characterized as a haven for hacks. During a chance meeting with Vidal in Los Angeles when Katakis was a warm-up singer for the Herb Alpert band, the young musician felt his life change, and he became a photographer and writer with a Vidalian urge to explore, and to question.

Katakis’s famous photo of Maya Lin, the artist of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, became contentious when he challenged an act of censorship by the National Portrait Gallery and asked for the picture’s return.

His famous photo of Maya Lin, the artist of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, became contentious when he challenged an act of censorship by the National Portrait Gallery and asked for the picture’s return. His books include Photographs and Words with Dr. Kris Harden, co-authored with his late wife, a beloved anthropologist and ideal life-mate. Traveller: Observations from an American in Exile, published in 2009, has a foreword by Michael Palin, a fellow traveler and friend.

Like Vidal, Katakis thinks that the myth of American exceptionalism is not only foolish, but dangerous. Like Vidal, he favors living abroad and seeing Americans as others see us: self-involved but unreflective; self-righteous, but also hypocritical; militantly religious and religiously militant; obsessed by money and addicted to oil; shrewd in deal-making, yes, but easily duped by flag-pin politicians.

Like The Grapes of Wrath, Katakis’s book telegraphs its message through the metaphor contained in its title.

Like a Hemingway novel that anchors the ideas expressed in experience, A Thousand Shards of Glass consists of a series of episodes—9/11, Kris’s death, meeting Gore Vidal—described in short sentences and simple words to convey their meaning. Like The Grapes of Wrath, Katakis’s book telegraphs its message through the metaphor contained in its title. As the author explained it to an Australian interviewer in 2014, “In order to understand America one must realize that it is not a country, it’s a store where everything is for sale, every principle, ethic and friend.” The job of a serious writer, then—like that of the photojournalist—is to reveal the face under the makeup, the reality behind the myth.

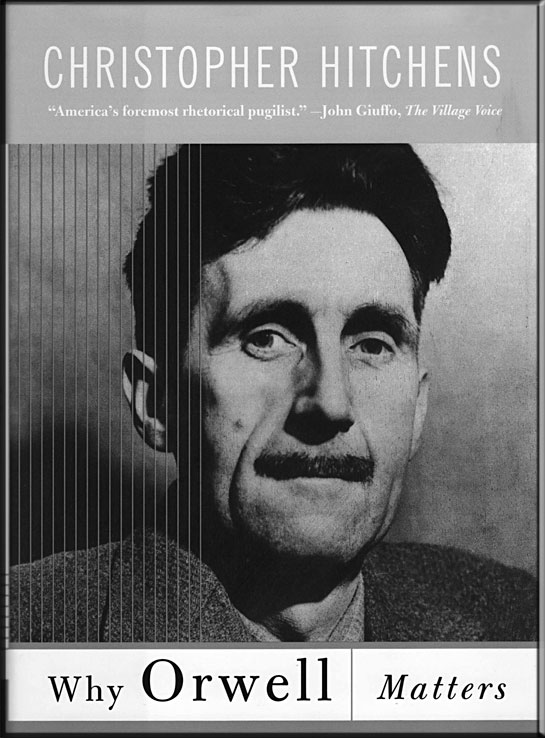

Katakis’s picture of America, like Steinbeck’s, isn’t always pretty. Kris, diagnosed with a brain tumor in the prime of life, becomes a tragic victim of the pre-Obama American health care horror show. Vidal is first encountered on a TV set decades earlier, talking with Eugene McCarthy about America’s disastrous involvement in Vietnam. Since then the US has doubled down, a nation of true believers where (to paraphrase Christopher Hitchens) religion ruins everything and (Vidal again) history teaches nothing. Clint Eastwood, the former mayor of Carmel, California, insults an empty chair at the 2012 Republican convention, an embarrassment Katakis recalls when he passes Eastwood in a hospital hallway.

Like a Hemingway novel that anchors the ideas expressed in experience, A Thousand Shards of Glass consists of a series of episodes described in short sentences and simple words to convey their meaning.

Bush’s phony Iraq war is fought in the name of Americans by 1% of the population living at the opposite end of the economic spectrum from Wall Street’s 1%. Hitchens, a guiding light to Katakis, loses his luster after 9/11, buying into Bush’s war in the Middle East for reasons Katakis ascribes to Hitchens’s upbringing as the son of a World War II vet. Katakis’s journal entry on 9/11 begins “. . . today hard terrorism hit soft terrorism.” Another, written four years later, describes Bush’s Rasputin, Karl Rove, dancing at a White House Correspondents’ dinner to the delight of reporters who are still high on the Bush & Company cool aid. Eventually, even the Beltway woke up and smelled the coffee, but Karl Rove’s victory dance is a useful reminder of how madness overtook America before Iraq imploded and sobriety set in.

Which raises the challenge posed by the book: do Americans never learn? Katakis explores the problem of American amnesia with people he meets in London, Paris, and Italy; like Hemingway and Vidal, he has perfect pitch in conversation, and he records what others say us with an infallible ear. His diagnosis of America’s mania for guns is framed by a fraught encounter with a woman from Eastern Europe, in London, following the Newton, Connecticut school shooting. “I think we Americans are afraid of each other, of everything,” he explains, despite “the fictional narrative of America that we have been selling for some time now.”

Quoting Hemingway, Katakis compares the global dominance of America’s ‘consumer corporate state’ with Britain’s East India Company two centuries ago—an undertaking of naked power wearing the fig leaf of moral righteousness.

Savoring Paris as Hemingway did decades earlier, he celebrates “the poetry of living” encountered abroad, the daily joie de vivre Americans have lost in “our obsession with our devices.” Quoting Hemingway, he compares the global dominance of America’s “consumer corporate state” with Britain’s East India Company two centuries ago—an undertaking of naked power wearing the fig leaf of righteousness. He and Kris move to Europe to protest Bush’s war, and to enjoy the poetry of living now lost in America, “the land of lists.” Their idyllic life abroad is interrupted by her father’s death; her diagnosis prevents their return. Numbed by her death, Katakis writes, “I have come to know that most Americans are sleepwalking.”

Like Vidal and Hitchens, Katakis is hard not to quote, and A Thousand Shards of Glass contains equally memorable sentences in abundance. So does a conversation with Katakis, as I learned over lunch in Carmel, California late last year, when I asked him if he thought the Bernie Sanders insurgency showed that Americans are finally waking up. He said yes, repeating the comment, quoted earlier, that he made to the Australian interviewer about America’s self-illusion in 2014. When his wife died he lost the “true north” in his life, but he’s getting his bearings again, and a note of hope for an awakening has emerged in his writing.

Fans of Hemingway, Steinbeck, Orwell, Vidal, and Hitchens—the bright constellation in Katakis’s dark sky—will delight in his references and allusions to their writing in A Thousand Shard of Glass. Bernie Sanders supporters will discover that, on almost every issue, Katakis was there first, before the presidential campaign brought American exceptionalism into question on problems of foreign and domestic policy. In response to my followup question about presidential politics before writing this review, Katakis said this:

I have often wondered what it means to be moral or how to live an ethical life in accelerated and morally ambiguous times which have seemingly allowed for rationalizations of thoughts and conduct by individuals and institutions, that just a short time ago, would have been considered unacceptable and injurious to the common good. Marcus Aurelius wrote that “the soul becomes dyed with the color of it’s thoughts,” suggesting one of the steps toward morality was the self control of our darker selves. Gore Vidal wrote that ‘we’ Americans, ” learn nothing because we remember nothing.” That is painfully demonstrated by any objective observer watching the 2016 Republican presidential primary. We have lost our way. If we remembered our own history, we would hear in the voice of Donald Trump, and his supporters, the voices of Father Coughlin and Senator Joseph McCarthy. They would hear the fear mongering and the insults that have been the tried and true tactic of scoundrels who have never offered anything but a scorched earth. But we Americans, in our ignorance and conceit, do not know our history and, as a collective, are not a good people. To those dark voices among us I can think of no more eloquent response than that of Mr. Joseph Welch to Senator Joseph McCarthy on June 9, 1954: “You have done enough. Have you no sense of decency sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?”

John Steinbeck invited his readers to participate in his fiction. Overhearing Gore Vidal changed Michael Katakis, helping him to become a writer. Participate in the result of that inspiration by reading A Thousand Shards of Glass. You’ll change, too.

Characterizing Americans as sleepwalking would ignore the basic Jungian concept of individuation. As I have tried to point out in many essays, we share the planet and the nation with individuals who are at one of four (or more) different levels of evolution. The lowest, who are almost totally unconscious, may appear to be sleepwalking, but have in fact never been truly awake. The second level includes those who are awakening to their uniqueness and as a result beginning to manifest an Ego. They are still mainly unconscious but tend to project onto external gods and heroes (e.i., Donald Trump supporters). At the next level are those with fully developed Egos that have become the center of their perceived self. At the highest level, those who realize that there is more to the Self than the Ego, and begin to explore this new psychic territory, have experienced what the Ed Ricketts described “breaking through.” Some who believe “sleepwalking” is at the heart of the problem may suggest a remedy such as a slap to the side of the head, but waking an individual who has never been conscious produces results quite different from awakening a person undergoing with a momentary lapse of consciousness. We would be wiser to support a plan that methodically acknowledges evolving individuals and their struggles on the path to the Self.

Wes Stillwagon, Lillington, NC

Wes Stillwagon writes about the Jungian interpretation of John Steinbeck at this site.

Will, After sending you a link to Bill Curry’s analysis of Hilary Clinton and Bernie Sanders (link below) I read (and greatly appreciated) your Broken Nation article. It’s all of a piece, as my friends in England would say. I have lived through the terrible and insulting years of the House Un-American Activities Commission (HUAC), the incredible years of Joseph McCarthy, the assignations of President Kennedy and his brother Robert, the lynching of Emmett Till, the murders of Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers, and the numerous sit-ins and bus-ins that forced integration (sort of) on the states of the former Confederacy. Moreover, time and again I have witnessed how 1% of our population has been sent overseas to fight and die in no-win wars concocted by and for the 1% who profited from them. This, as Michael Katakis so rightly asserts, is a broken nation, and your review has made me wonder what the Romans snacked on during their Games. And whether they watched to be entertained…or for the commercials?

Link:

http://www.salon.com/2016/02/23/its_the_corruption_stupid_hillarys_too_compromised_to_see_what_donald_trump_understands/?source=newsletter

Katakis’s essays are less analytical than a personal reaction to the world around him, which gives them their incredible energy and passion.

In John Steinbeck’s “Bombs Away The Story of a Bomber Team” he cautions against misjudging a nation based upon its apparent disunity, strife, or struggles. He argues that those indicators evidence strength and potential not weakness. He predicted that Japan and Germany really misjudged the USA considering it weak and spineless– a nation that would quickly sue for an armistice to the advantage of the aggressors. Let’s face it, It would be easy to wrongly judge this nation based upon 2016 election news alone. Steinbeck would not be surprised to learn that China spends seven times its defense budget on internal security as the central committee perceives the threat to their absolute rule comes from the youngest citizens of the country who seem to be regularly breaking rules of order and their dictates even in the face of very harsh punishment. It is the “individual” and not the social body that should be understood.

I find Dr. Ray’s piece about my book insightful and well articulated. While I see many Americans overcome with fear and seemingly always poised to be offended, I am not in that camp nor sympathetic. However I must take issue with Mr. Stillwagon’s comments of February 23.

Mr. Stillwagon makes the classic American error of trying to find, in his case with psychology, rationales for why Americans are behaving the way they are and incorrectly assumes that the criticisms in my book are current rather than long standing ones. Mr. Stillwagon’s explanation regarding my view that Americans are now ‘purposely unconscious’ does not disprove my point nor further clarify the points Dr. Ray’s article articulates so well.

I have watched America and Americans from the United States and from abroad for over forty five years and have been writing essays about what I have seen and experienced for nearly thirty. It has been a long and steady decline. It did not have to be that way. Where we Americans find ourselves now is, as Gore Vidal said, at the end of empire. One of the ancients wrote that “Myth is what never was but always is,” and we Americans have taken the fictionalized myths about our goodness to the point that it has cloaked who we really are and what we have done even from our selves. Seeing that Mr. Stillwagon wished to employ Jungian psychology in trying to explain where we are today, I would like to bring in Dr. Freud who, when trying to explain repression, suggested that ‘repression is forgetting and forgetting that you’ve forgotten.’ We know longer know who we are, or do we? Perhaps we find the romanticized fiction we have constructed about ourselves more palatable than what our unvarnished history tells us. Like Freud I believe that the way we start to get well is by telling the truth about ourselves to ourselves and each other.

To understand America today is not a complicated affair. If one looks at the USA as a country then one gets frustrated and confused by it’s actions, through policy and legislative action, that reduces it’s citizens to harvestable crops for the benefit of corporations and banks. Once someone understands that America is not a country but a store, then all of our conduct and decisions start to make sense. If what I suggest is accurate, and I believe it is, then it seems only right that in the United States of Salesmen large numbers of people would finally rally around a salesman whose words are as empty as a carnival barker’s.

Voltaire wrote that uncertainty was an uncomfortable position but certainty a ridiculous one. Many in America today, especially people of the right, seek that nirvana of strength and certainty no matter how untrue. Trump, and others offer all that and more. Only in a nation, where people have replaced knowledge and reason with fear, anger and prejudice can someone like Mr. Trump and others be listened to. This nation of customers must remember, buyer beware.

Contrast the little Norwegian Village in Steinbeck’s “The Moon Is Down” and a hypothetical village of Trump supporters

Would valuable humanities lessons be acquired by contrasting the fictional occupied Norwegian village depicted in John Steinbeck’s “The Moon Is Down” with a hypothetical village of supporters of Donald Trump? I believe there are valuable humanities lessons to be had with such a study and I’d like to table them for discussion.

Of course I am assuming the reader has read “The Moon Is Down” to fully understand the contrasted points.

The little Norwegian village in the novel was occupied by the Nazis. The village became a real problem for the occupying authority because the officer-in-charge, a Colonel Lanser was from a nation ruled by absolute vertical authority, a dictatorship similar to that seems to be preferred by Donald Trump. In order to relieve his frustration he appealed to the mayor of the village assuming he also wielded absolute authority. But it was a different kind of social body in the little village, one made up of individuals who were accustomed to making their own minds up in the face of life challenges. The role of the village mayor was quite different than one who dictated with absolute rule.

Contrasting the Nazi state of Colonel Lanser, where the population served the dictator to the little Norwegian village, where the mayor served the population. Two distinctly different social groups. You can tell how Trump would dictate by watching his commands to get any agitators out of his rallies. He would do the same if he were president. Adolf Hitler made many mistakes in his short reign., many because he didn’t listen to his generals. Most of the advisors were afraid to say anything to him that he would not like. I suspect that Donald Trump who seems to have forgotten that he is wealthy because of an inheritance not because of his wisdom, surrounds himself with yes men who are also afraid to express opinions that may contradict his own.

Given the relationship between the little village mayor and the citizens described by Steinbeck, it seems most were highly independent who cherished their freedom and liberty. They saw the mayor’s role as serving the common good and not one of absolute authority. It appears to me that Trump supporters are close to the lowest level of human evolution or adult maturity. Such individuals unconsciously project upon external gods, Superman, and father figures to protect them from their real and imagined fears. The winning majority in Germany, a mere thirty three percent of the voting population was also at that level of human involvement. Herein lies the danger of the Trump campaign.

Steinbeck’s concept of phalanx also must be considered with lower-levels of adult maturity. Since the lower levels are mainly unconscious the phalanx may have a considerable impact on group behavior as described by Mac in Steinbeck’s in Dubious Battle.