The August 22 New York Times story by Adam Liptak—“Supreme Court to Consider Legal Standard Drawn From ‘Of Mice and Men’”—suggests that a book by John Steinbeck, like the Bible itself, is open to misinterpretation whenever there is a point to prove. In response to the Supreme Court’s 2002 decision barring execution of the “intellectually disabled,” reports Liptak, “Texas took a creative approach, adopting what one judge there later called ‘the Lennie standard,’” so named for Lennie Small, the mentally handicapped farmhand who kills and gets killed in Of Mice and Men. “This fall, in Moore v. Texas, No. 15-797,” Liptak continues, “the United States Supreme Court will consider whether the Court of Criminal Appeals, Texas’ highest court for criminal matters, went astray last year in upholding the death sentence of Bobby J. Moore based in part on outdated medical criteria and in part on the Lennie standard.”

The story by Adam Liptak suggests that a book by John Steinbeck, like the Bible itself, is open to misinterpretation whenever there is a point to prove.

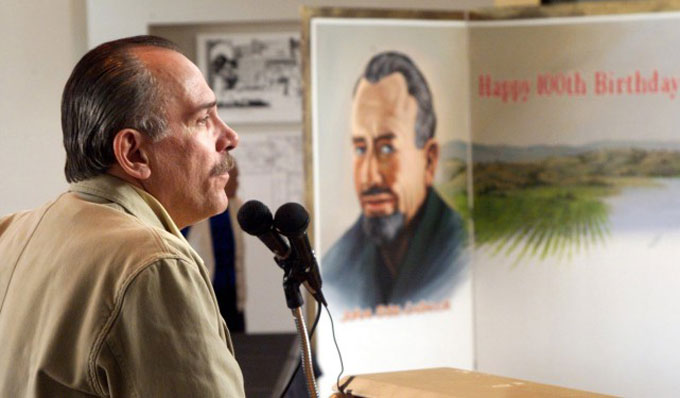

John Steinbeck explained that his fictional character was based on fact in a 1937 New York Times interview quoted by Liptak. “Lennie was a real person,” Steinbeck told the Times. “He is in an

insane asylum in California right now.” Responding to the misuse of his father’s novel when the Texas case made news in 2012, Thomas Steinbeck—a novelist very much in his father’s image—objected in the strongest terms. “The character of Lennie was never intended to be used to diagnose a medical condition like intellectual disability,” he said at the time. “I find the whole premise to be insulting, outrageous, ridiculous and profoundly tragic [and] I am certain that if my father, John Steinbeck, were here, he would be deeply angry and ashamed to see his work used in this way.”

Lessons from Literary Criticism for the Supreme Court

Of Mice and Men is popular with middle and high school students, yet legal authorities continue to misread the author’s intention, as noted in Liptak’s story. The Supreme Court’s decision regarding the Lennie standard seems certain to set a precedent for legal debate about the death penalty, so understanding what Steinbeck intended matters. Judges like source citations, and reviewing literary criticism written around Steinbeck’s intention in Of Mice and Men may clarify their thinking. The brief summary of literary criticism that follows is intended to spare Steinbeck from further misreading as arguments over eugenics, euthanasia, and the Lennie standard unfold in the courts.

Of Mice and Men is popular with middle and high school students, yet legal authorities continue to misread the author’s meaning.

Fundamental to the death penalty debate is understanding what Steinbeck meant by having George execute Lennie at the end of the novel. Charlotte Hadella and critics have questioned the inevitability of this ending, the so-called mercy killing carried out by George at Slim’s urging as something that must done to spare Lennie from being lynched. George looks up to Slim, a figure of respect whose word counts among the menon the ranch. But Slim’s motives are murky, and he is associated with earlier killings in the novel—the shooting of Candy’s dog and the elimination of Lulu’s unwanted puppies.

Fundamental to the death penalty debate is understanding what Steinbeck meant by having George execute Lennie at the end of the novel.

Likewise, Louis Owens’s reading of the novel revolves around “the various deaths that punctuate the story,” beginning with Slim’s drowning of four puppies from Lulu’s litter. Carlson takes the opportunity to agitate for saving one puppy for Candy so that they can shoot Candy’s old dog, whose offense is that he “stinks.” In an attempt “to give his argument the kind of humanitarian bent euthanasia proponents prefer,” Carlson tells Candy it’s cruel to keep the dog alive—even though there is nothing to indicate that the animal is suffering or unhappy—and a killing of convenience suddenly seems inevitable. Candy appeals to Slim, who takes what Hadella calls “an enormous ethical leap” by saying he wishes someone would shoot him if he got “old and crippled” like the dog. Or like Candy himself, who Owens suggests may have cause to wonder whether Slim will decide to shoot him too someday. Like Lennie and Crooks, Candy is just the kind of character Curley’s wife calls weak—“unproductive,” “valueless,” inconvenient like his dog.

The Gun: Connecting Eugenics, Execution, and Fascism

Steinbeck makes the parallels between the dog’s shooting by Carlson and George’s shooting of Lennie unmistakable, for both are shot “in exactly the same way with the same gun.” As Owens notes, “Dog and man are both annoyances and impediments to the smooth working of the ranch. One stinks and one kills too many things.” When the body of Curley’s wife is discovered, George’s first impulse is humane, to capture Lennie and lock him up so he won’t be a danger to society. But Slim objects. Using the rationale that justified killing Candy’s dog, Slim argues that Lennie would be better off dead than incarcerated—in Slim’s words “locked up, strapped down, and caged.” Slim, Owens observes, “is playing God.” Significantly, the gun used for these killings is described as a Luger, according to Owens a deftly emphasized detail intended by Steinbeck to associate them with eugenics and fascism in Germany.

The gun used for these killings is described as a Luger, according to Owens a deftly emphasized detail intended by Steinbeck to associate them with eugenics and fascism in Germany.

In support of this point, Owens demonsrates Steinbeck’s familiarity with studies of eugenics whose conclusions were used to justify the forced sterilization of those deemed defective by the Heredity Court in Hitler’s Germany. Their Blood Is Strong, the title of the predecessor to The Grapes of Wrath, shows Steinbeck’s familiarity with when he wrote Of Mice and Men. As Owens points out, the ominous repetition of the word Luger in the novel clearly connects “the supposed ‘mercy’ killings of the novel with the rise of Fascism in Germany.”

Their Blood Is Strong, the title of the predecessor to The Grapes of Wrath, shows Steinbeck’s familiarity with eugenics when he wrote Of Mice and Men.

In the light of literary criticism, then, Of Mice and Men can be understood as a cautionary tale written in response to current events. Accepting Lennie’s and the dogs’ deaths as inevitable, as mercy killings that simply must be done, is contrary to Steinbeck’s meaning, the act of misappropriation pointed out by Thomas Steinbeck in his comments about his father and capital punishment. Furthermore, Slim’s inviting George to have a drink after shooting Lennie is an invitation to accept a worldview in which life is nullified—the Nazi world of eugenics, euthanasia, and extermination. This worldview is reflected in current political rhetoric about racial purity, national identity, and the justification of police violence and mass deportation.

This worldview is reflected in current political rhetoric about racial purity, national identity, and the justification of police violence and mass deportation.

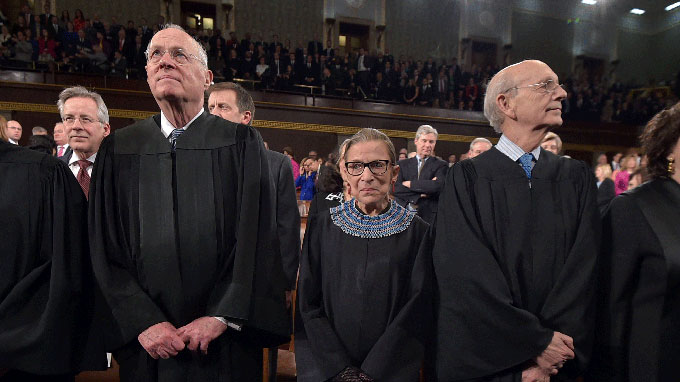

Both presidential campaigns remind us that the sanctity of the Supreme Court depends on the outcome of the election. Both would benefit from understanding the moral questions raised by John Steinbeck in Of Mice and Men. Where is our compassion? Who will care for the Lennies of our world today? As for the Supreme Court as presently constituted, I have this advice: read Steinbeck’s novel—closely, slowly, carefully, paying attention to details—and read with your heart, as Steinbeck intended for all his books. Though it may seem so sometimes, America isn’t Nazi Germany. Don’t use Steinbeck’s story as an excuse to execute those who are mentally ill or intellectually handicapped because they don’t pass the Lennie test.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Hadella, Charlotte Cook. Of Mice and Men: A Kinship of Powerlessness. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1995.

Heavilin, Barbara A. John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men: A Reference Guide. Westport, Connecticut, 2005.

Owens, Louis. “Deadly Kids, Stinking Dogs, and Heroes: The Best Laid Plans in Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.” Steinbeck Studies. (Fall 2002), 1-8.