John Steinbeck not only liked being painted, he liked artists and had a deep affinity for the visual arts. For much of his life he counted artists among his most trusted friends. His appreciation for the visual arts, and the needs of working artists, started on the Monterey Peninsula and continued in New York. As suggested by this undated photograph of Steinbeck with his son Thom, he passed this appreciation on to his children. As a result, of the great American writers of the 20th century perhaps none has been captured in portraits and drawings as often as John Steinbeck.

I think there are two main reasons for Steinbeck’s attraction to artists and being a subject of their work. The place where Steinbeck lived for much of his first 40 years, California’s Monterey Peninsula, was thick with gifted artists when Steinbeck was growing up and beginning his career. And because what Steinbeck was writing in the 1930s and 40s did not make him particularly popular with the local establishment, even endangering him, his circle of friends was necessarily limited, and included artists. This connection with artists carried over when Steinbeck moved to New York and eventually extended to Europe as well. I have a 2001 letter from the late Thomas Steinbeck in which he wrote, “By the time I showed up on the scene, my father had already sat for a number of notable painters.’’ Thom “showed up’’ in New York City, where he was born to John Steinbeck and Gwyndolyn Conger in 1944.

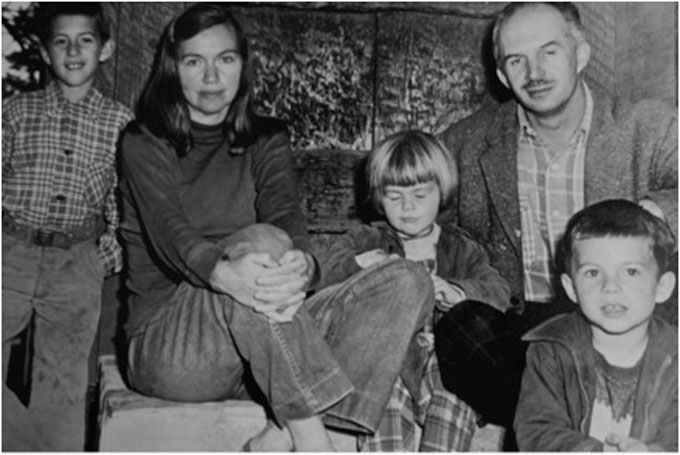

Three major portraits of Steinbeck that we know of were made before he left California for New York. One was by James Fitzgerald. The other two were by the husband-and-wife artists Ellwood Graham and Judith Deim, shown here with their children in an unattributed photograph from the late 1940s or early 1950s.

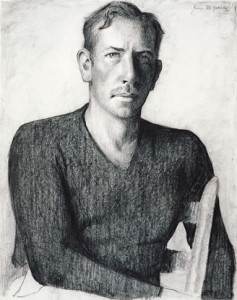

Fitzgerald was born in Milton, Massachusetts and arrived in 1928 as a seaman aboard a freighter. Once he settled in Monterey, he became a part of the group of writers and artists who gathered at Ed Ricketts’s legendary lab on Cannery Row. In 1935, the year Tortilla Flat was published, Fitzgerald did this charcoal study of a young, gaunt Steinbeck, his face half in shadow, that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. Reportedly Steinbeck and Fitzgerald had their disagreements, but their friendship endured. There is a photograph of Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, and Ricketts standing on Cannery Row with improvised musical instruments in their hands, including pots and pans. Fitzgerald left Monterey in 1943 for Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine; several years ago the Monhegan Museum established the James Fitzgerald Legacy in honor of his standing as one of America’s greatest watercolorists.

Fitzgerald was born in Milton, Massachusetts and arrived in 1928 as a seaman aboard a freighter. Once he settled in Monterey, he became a part of the group of writers and artists who gathered at Ed Ricketts’s legendary lab on Cannery Row. In 1935, the year Tortilla Flat was published, Fitzgerald did this charcoal study of a young, gaunt Steinbeck, his face half in shadow, that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. Reportedly Steinbeck and Fitzgerald had their disagreements, but their friendship endured. There is a photograph of Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, and Ricketts standing on Cannery Row with improvised musical instruments in their hands, including pots and pans. Fitzgerald left Monterey in 1943 for Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine; several years ago the Monhegan Museum established the James Fitzgerald Legacy in honor of his standing as one of America’s greatest watercolorists.

Graham and Deim were both born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1911. Sometime in 1936 or 1937 they met Steinbeck and Ricketts–who were on their way to Mexico–while working on a WPA mural project at the Ventura Post Office in Southern California. The fiction writer and the marine biologist from Pacific Grove were impressed by the work and invited the young couple to visit the Monterey Peninsula, where Deim and Graham eventually settled. Steinbeck was generous, paying their way to Mexico to learn to “paint out loud,’’ advising them, Deim later wrote, to “go to Patzcuaro and not to Tasco where all the tourists go.’’

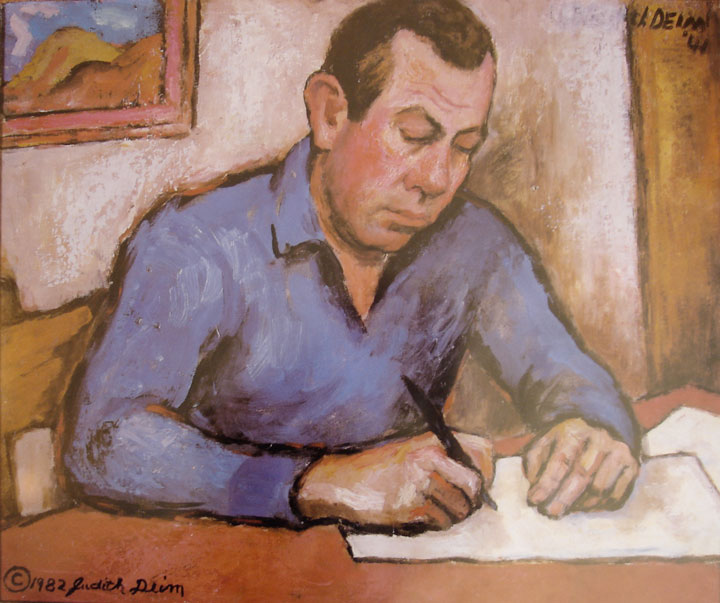

In 2000 Deim wrote that when Steinbeck and Ricketts returned from their expedition to the Sea of Cortez in 1940 “there was much rejoicing, partying, storytelling at the Lab. After a few days of this . . . John felt it was time to get to work. He said, ‘Why don’t you kids paint my portrait and I shall be forced to concentrate and get on with my book.’” Deim’s modern, compact portrait of Steinbeck in the act of writing, shown here, now hangs at the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies in San Jose.

Ellwood Graham’s psychological study of John Steinbeck (above) has been missing for decades. One story says that Steinbeck’s friend, the film director John Huston coveted the painting, another that it was won or lost in a poker game. Its discovery, if it still exists, would be a major find.

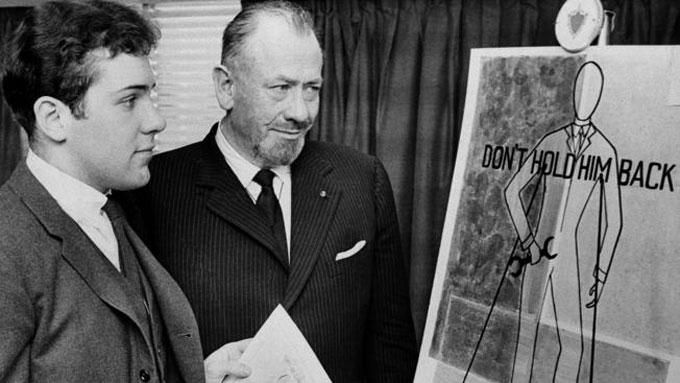

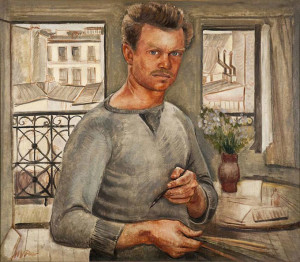

One of the first artists Steinbeck became friendly with in New York was Henry Varnum Poor, shown in this self-portrait. In the early 1940s Poor was, like Steinbeck, a resident of Rockland County, and he agreed to be a character witness for Steinbeck in 1942 when the writer applied for a New York State pistol license. This took some courage because Poor had executed a major mural in the Department of Justice building in Washington, and Steinbeck was controversial.

One of the first artists Steinbeck became friendly with in New York was Henry Varnum Poor, shown in this self-portrait. In the early 1940s Poor was, like Steinbeck, a resident of Rockland County, and he agreed to be a character witness for Steinbeck in 1942 when the writer applied for a New York State pistol license. This took some courage because Poor had executed a major mural in the Department of Justice building in Washington, and Steinbeck was controversial.

In 1944 John and Gwyn commissioned Poor to do a Steinbeck family portrait, with Gwyn holding a crying infant Thomas. It’s a stark painting. Thom, who disparaged his depiction by Poor in the 2001 letter, added that “My mother loved this painting above all others, which only lends credence to Mr. Poor’s interpretive skills.’’ Whatever he thought of Poor’s painting—which now belongs to the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas—John Steinbeck continued the family-portrait habit. Thom, again in his 2001 letter, noted that “before I could tear myself from the ancestral grasp, my portrait had been painted three times.’’

By maintaining his relationship with artists in New York, it’s possible that Steinbeck wanted to help keep them employed, as he had for Graham and Deim back on the Monterey Peninsula. Thom writes about his father’s close friendship in New York with “that singular genius William Ward Beecher.’’ Thom and his brother Johnnie were fascinated by Beecher’s work but were “pole-axed’’ when their father told them Beecher would paint their portrait, which they realized meant lengthy sittings, away from mischief-making. Thom later recalled that when he and John misbehaved their father took out his frustration by “shaking his fist’’ at his sons’ portraits rather than at them.

Another Steinbeck portraitist was the handsome Swedish artist Bo Beskow (left), who painted or drew the writer at least three times. Beskow remained a trusted confidant during a three-decade relationship in which the two friends exchanged letters, notes, and encouragement, sometimes under trying circumstances. Beskow’s informal 1946 portrait of a smiling John Steinbeck illustrates the fall 2012 issue of Steinbeck Review. A Beskow drawing of Steinbeck with the notation “Copenhagen, Dec. 8, 1962’’—two days before Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize speech—came to auction several years ago.

Another Steinbeck portraitist was the handsome Swedish artist Bo Beskow (left), who painted or drew the writer at least three times. Beskow remained a trusted confidant during a three-decade relationship in which the two friends exchanged letters, notes, and encouragement, sometimes under trying circumstances. Beskow’s informal 1946 portrait of a smiling John Steinbeck illustrates the fall 2012 issue of Steinbeck Review. A Beskow drawing of Steinbeck with the notation “Copenhagen, Dec. 8, 1962’’—two days before Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize speech—came to auction several years ago.

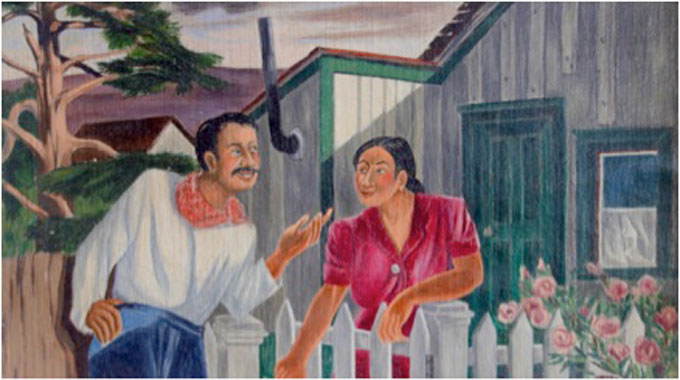

Of course artists didn’t depict Steinbeck only in portraiture. Judith Deim’s late-1930s painting “Beach Picnic’’ shows Steinbeck, Ricketts, and other members of the lab group gathered on an unidentified Monterey Peninsula or Big Sur beach. Deim said the painting, which has a pensive quality, was done when threats were being made against Steinbeck and his friends gathered around him protectively, as the composition suggests.

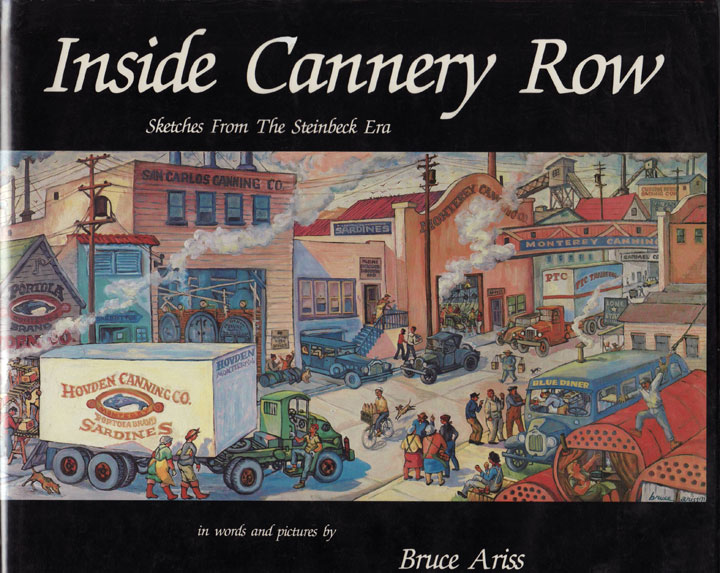

Bruce Ariss, another prominent Monterey Peninsula artist from the lab group, did an arresting drawing of Steinbeck sitting under a cypress tree watching as the characters he created parade by on a busy Cannery Row. Ariss’s spontaneous drawings of Steinbeck and Ricketts and the others populate his book Inside Cannery Row: Sketches from the Steinbeck Era. Some of Ariss’s images can be seen today on the colorful banners that dot Cannery Row.

Not all of Steinbeck’s artist friends drew or painted him. Armin Hansen and Howard Everett Smith were leading artists on the Monterey Peninsula with close relationships to Steinbeck, but I know of no portrait of the writer by either one. Hansen wasn’t really a portraitist, so it’s unlikely he painted Steinbeck. Smith did do portraits: perhaps his most famous subject was the poet Robinson Jeffers, after John Steinbeck the Monterey Peninsula’s greatest literary figure.

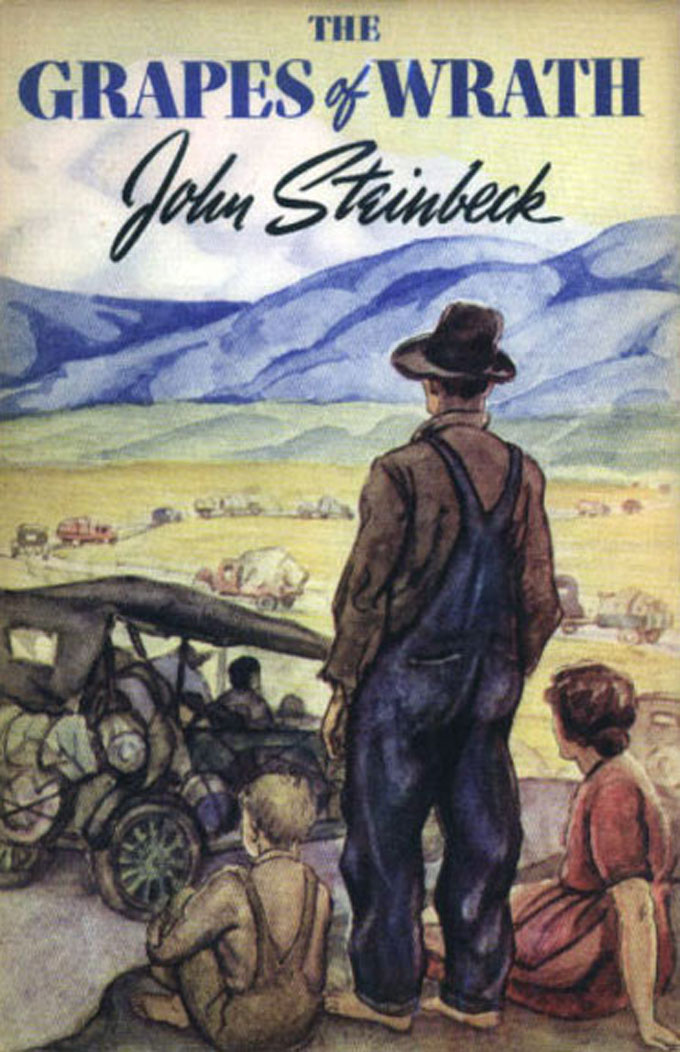

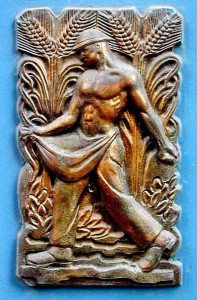

And then there were the illustrators of Steinbeck’s books. Mahlon Blaine, an artist Steinbeck met in 1925 while traveling to New York for work, created the cover art for Cup of Gold, Steinbeck’s first novel. Steinbeck was unsatisfied with the image, and he continued to be involved in selecting illustrators for many of the works that followed. To create the cover art and illustrations for the deluxe edition of Tortilla Flat like the one shown here, he helped choose Peggy Worthington (later Peggy Worthington Best), the wife of a poet and editor at Viking Press, his publisher. Thomas Hart Benton, the Missouri populist painter, was a natural choice to illustrate Viking’s deluxe edition of The Grapes of Wrath.

I’m uncertain whether Steinbeck knew Elmer Hader, the California artist who created the dust jacket for the first edition of the novel in 1939. Both Steinbeck and Hader were from Monterey County, Hader born in 1889 in the little town of Pajaro, not far from Salinas. If Hader wasn’t personally acquainted with the author, he certainly understood The Grapes of Wrath. His inspired image of the Oklahoma Joads seeing California for the first time has become almost as iconic as the characters themselves.

Some years ago I was contacted by the auction house that was putting the original watercolor for Hader’s Grapes of Wrath cover up for auction. They asked what I thought it should sell for. Guessing, I said $30,000-$35,000. That seemed high, they replied, since no Hader painting had ever sold for more than a tenth of that amount. Looking back today it’s obvious the eventual purchaser got a bargain . . . for $65,000.

I think Steinbeck would have smiled at that result. He liked artists and he wanted them to receive their due, preferably while they were alive. He passed on his affinity for the visual arts, and he did what he could to help the artists he knew.

This is the 300th post published by SteinbeckNow.com since the site launched three years ago. View the related video—Steinbeck’s Storied Artists, with commentary by Steve Hauk—from the site’s YouTube channel.—Ed.