The Leader

I believed the leader

when he said I wasn’t free

all because of the people

who didn’t look like me

I followed my leader and became

his tool and helped break the

back of the golden rule

I did nothing when the truth

was murdered by lies and silent

when the children screamed and

died

I did what I was told

I took down names not

knowing someone else was

doing the same

I followed my leader when I

knew it was wrong because I was

afraid of not going along but now

in this room with no door or light

it is me they accuse of not being right

I followed my leader until today when

they walked me up to my freshly

dug grave

Socrates had it right, Will and the Buddha did

too, follow no one, question and to thine own self

be true

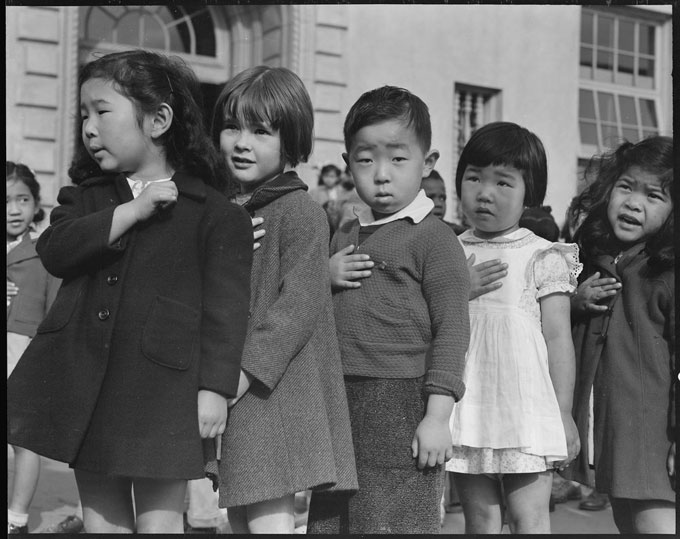

Photograph of Japanese internment during World War II by Dorothea Lange