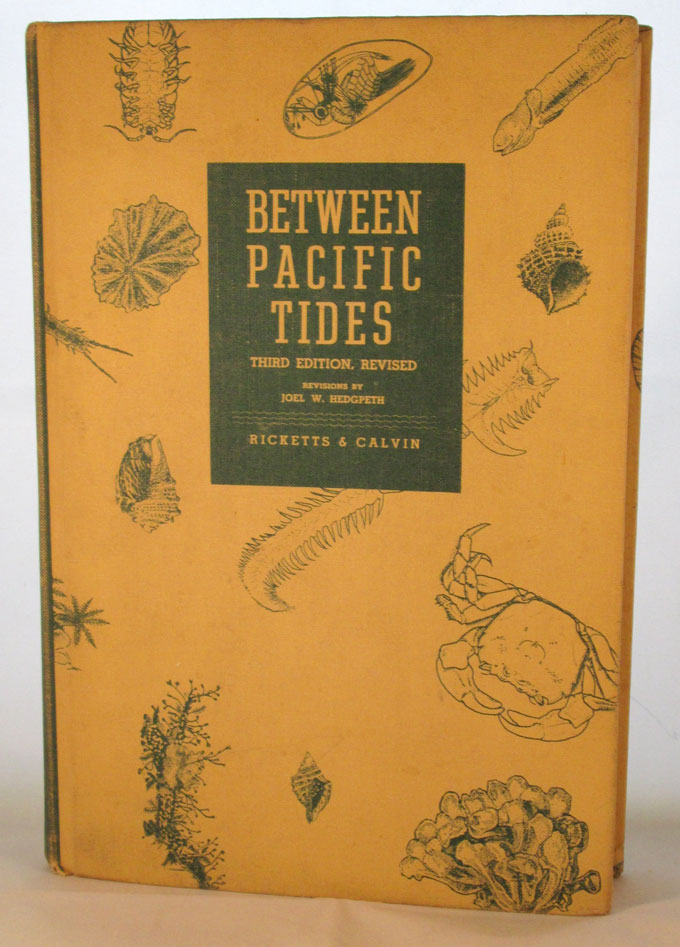

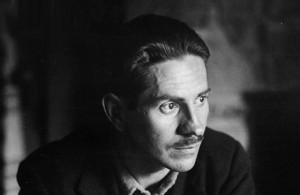

John Steinbeck was born on February 27, 1902 in the front bedroom of the Victorian house at 132 Central Avenue in Salinas, California. In 1905 he was christened in the parlor of the Queen Anne-style structure—the same room where he later practiced the piano. In the living room he announced that he intended to become a writer. In the basement he regaled neighborhood friends with ghost stories and other tales. In an upstairs bedroom he wrote short stories that he sent to magazines, unsigned, as a teenager. He left for Stanford in 1919; years later he and his wife Carol returned to help care for his dying mother, a former school teacher who insisted that all four of her children go to church, learn piano, and attend college. In the same upstairs bedroom he occupied as a boy he continued to work on The Red Pony and Tortilla Flat, the book that brought him fame when it was published in 1935, the year his father died.

In the upstairs bedroom Steinbeck occupied as a boy he continued to work on The Red Pony and Tortilla Flat, the book that brought him fame when it was published in 1935, the year his father died.

The home was sold following Olive’s death, near the bottom of the Great Depression, in 1934. For the next four decades—years of war, recovery, and modernization—ownership of the aging Victorian house passed through various hands until its purchase by the newly created Valley Guild in 1973. A 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization created to save the house where Steinbeck was born, the Valley Guild made repairs, conducted research, and produced results that are evident today. The bed in which Steinbeck was born was returned. So were Olive’s desk and table. Steinbeck’s sisters stayed in California, and they and their children and grandchildren made generous gifts of period furnishings and family heirlooms. Thanks to the hard work of Valley Guild volunteers, the Steinbeck House was added to the National Register of Historic Places, a prestigious designation with some practical benefits.

For the next four decades—years of war, recovery, and modernization—ownership of the aging Victorian house passed through various hands until its purchase by the newly created Valley Guild in 1973.

Recognizing the need for an income stream to support ongoing maintenance and preservation, the founders put their heads together and came up with a plan that serves educational and economic goals equally. For five days each week throughout the year the House is open to the public as a lunch restaurant, gift shop, and bookstore operated by a team of 98 dedicated volunteers. The restaurant employs a professional chef and offers a changing menu. Table service is provided by Valley Guild members in period dress—docents in motion who educate diners about Steinbeck while taking orders and serving food. The annual Steinbeck festival and the National Steinbeck Center on Main Street, three blocks from the Steinbeck House, are partners in the enterprise of keeping Salinas, California at the forefront of global interest in Steinbeck’s life and work.

Time Catches Up With Every Victorian—Even Steinbeck’s

Age has its advantages, but keeping a 119-year-old Victorian house in working order is expensive. Not long ago it was discovered that the center of the Steinbeck House, supported by eight posts on brick footings, was slowly sinking. The posts run the length of the basement gift shop and bookstore and serve as the building’s legs. As they go, so goes the body. To prevent collapse, soil engineers and construction experts determined that the deteriorating posts and bases had to be replaced using concrete. Although the restaurant has remained open during the process, the project required closing the gift shop and book store, raising the central beams, and installing temporary supports while making excavations and constructing permanent posts and footings—all necessary to insure the future of John Steinbeck’s birthplace as a public resource.

Using the GoFundMe Page Makes Giving Safe and Easy

The project is well along and, once all expenses are paid, is expected to cost $35,000. The bill, along with the revenue hole caused by the gift store closing, has created an urgent need for funds to keep the Steinbeck House open and operating in the black. The people of Salinas, California are community-minded and do their part. But the Steinbeck House is a national treasure, and help is also needed from friends and fans who live elsewhere. Fortunately this group is growing: visitors from 68 countries and 50 states have enjoyed lunch and a lesson in Steinbeck history while eating at the restaurant. Please do your part to keep the Steinbeck House on its feet. Visit the new GoFundMe page and make your tax-deductible gift to the project. The Victorian house where Steinbeck first wrote fiction is getting on, but just as beautiful as the day Steinbeck was born in the front room of his family home 115 years ago.