Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, a book of short stories by Steve Hauk based on the life of John Steinbeck, will be published by SteinbeckNow.com on July 22. The first print project undertaken by the website, it is the product of a two-year collaboration between Hauk—a playwright in Pacific Grove, California—and Caroline Kline, a Monterey artist with a flair for illustration and a feel for John Steinbeck, whose affinity for art and artists began when he was growing up in the Salinas Valley and eventually extended to Europe. Earlier versions of four of the short stories have appeared online at SteinbeckNow.com. All sixteen feature original art work by Kline inspired by Hauk’s fictional rendering of dramatic episodes—some real, others imagined—from Steinbeck’s storied life in Salinas, Pacific Grove, New York, and beyond.

Archives for May 2017

Bill Lane Center at Stanford University Examines John Steinbeck, Environmentalism

John Steinbeck and the environment was the subject of a May 10 symposium held at Stanford University and attended by students, teachers, and others. Guest speakers for the campus event, sponsored by the Bill Lane Center for the American West, included Susan Shillinglaw, William Souder, and members of the Stanford University faculty. The late Bill Lane—the legendary publisher and philanthropist for whom the Center for the American West is named—was born in Iowa in 1919, the year Steinbeck entered Stanford as a freshman. Lane also attended Stanford before building a lucrative publishing empire around Sunset Magazine, a Lane family enterprise headquartered in Menlo Park, California. A Teddy Roosevelt Republican (like Steinbeck’s parents), Lane was a leader in the movement to protect pristine California wilderness from commercial development by acquiring it privately and putting it into public trust. Follow this video link learn more about John Steinbeck as an environmentalist.

Trump-Age American Life And Victorian-Era Madness

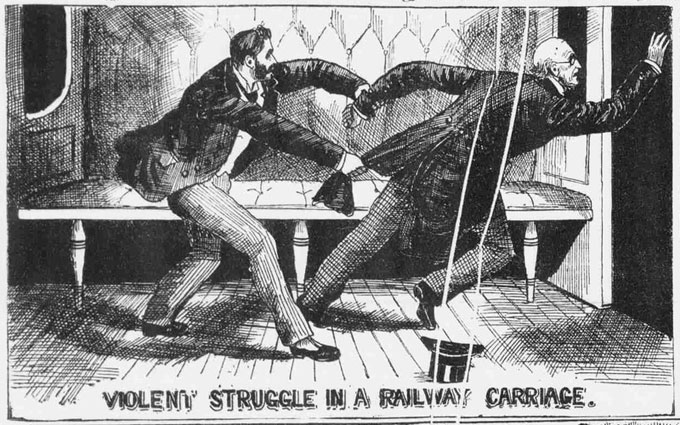

The Victorian Belief That a Train Ride

Could Cause Instant Insanity

Somewhere in Appalachia, a woman

is telling her oldest son not to strike back

at a fugitive father for having abandoned them.

The standard unit of pain is hers to call whatever

she wants since she wears the bruises like the son

wears Goodwill Levis and a t-shirt saying Tramps

Like Us, Baby, We Were Born to Run. The son isn’t

showcasing what he is, in his father’s cast-off t-shirt,

because Springsteen is the last word in Suffering. He

puts it on, the t-shirt, because what changes the way

we breathe is what we believe—though the Victorians

believed train rides could drive you mad. The riders

were rescuing themselves from the insanity of others

just by boarding. Just now, this one knots his leather-

and-scrap-wood tchotchke crucifix around his neck—

the cross is hollow and carries a powder they say

will kill you. I say what kills you isn’t the drug but

the hopelessness puts it there. Saying that, though,

is like floating on the wind through sainted hillsides

where row-house chimneys are censers distributing

God’s breath as coal smoke. The smoke is bruised

gold. It says how, even if there is no God and all

the days from Then to Now have handed us no

reason to hope, we still have a train to catch.

Inspired by an Atlas Obscura item linking Victorian-era train rides and mental illness.

Curing Verbal Tic Disorder On MSNBC’s Evening News

Last week I channeled my inner English teacher by urging greater attention to grammar in blog posts about John Steinbeck. As with Steinbeck, however, I had issues with my high school English teacher. Like Mrs. Capp, the Salinas High teacher who underestimated Steinbeck’s need for praise, a teacher named Margaret Garrett used negative attention against adolescent error at Page High School in Greensboro, N.C. Once a month in our senior English class each of us had to give a short speech without notes, facing the class and Mrs. Garrett’s gorgon gaze. Filler words—I mean, like . . . umm, you know—were sharply received. Uh . . . kind of, sort of, in any event—mumbling, cliché, butchered syntax produced a steep frown, and the noisy clap! clap! of Mrs. Garrett’s hard, red hands. The technique she used to cure teenage verbal tic-disorder was practiced and perfected and frightening. In my case it was effective, engendering a hypersensitivity to sloppy speech that makes the talking heads on MSNBC, my preferred purveyor of cable news, increasingly hard to watch and hear.

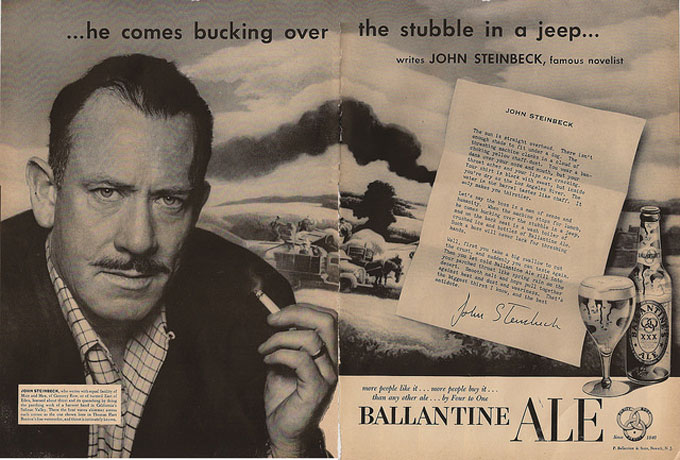

Compare the slow legato of John Steinbeck’s archived radio voice with the rapid staccato of Chris Matthews, Rachel Maddow, and Chris Hayes, who may be the most extreme example of stop-start arrhythmia on mainstream cable news. Close your eyes and count the filler words, clichés, and redundancies uttered by hosts and guests in an average on-air minute: I mean, you know, sort of, kind of, like . . . um, take a listen, tweet out, frame out, report out, break down, knock down, at the end of the day, now look . . . . Try to diagram the sentence that begins with this typical guest response: “Yeah, Chris, you’re absolutely right, yeah, but look [or take a listen to] . . . .” Imagine what John Steinbeck—a political sophisticate who thought bad syntax disqualified Dwight Eisenhower—would make of Donald Trump as president today, or of the contagious verbal tic disorder that has become the broadcast norm, corrupting discourse and advancing group-think. It’s the oral analog of thoughtless writing, caused by three attitudes Steinbeck abhorred: haste, inattention, and lazy following.

Compare the slow legato of John Steinbeck’s archived radio voice with the rapid staccato of Chris Matthews, Rachel Maddow, and Chris Hayes, who may be the most extreme example of stop-start arrhythmia on mainstream cable news. Close your eyes and count the filler words, clichés, and redundancies uttered by hosts and guests in an average on-air minute: I mean, you know, sort of, kind of, like . . . um, take a listen, tweet out, frame out, report out, break down, knock down, at the end of the day, now look . . . . Try to diagram the sentence that begins with this typical guest response: “Yeah, Chris, you’re absolutely right, yeah, but look [or take a listen to] . . . .” Imagine what John Steinbeck—a political sophisticate who thought bad syntax disqualified Dwight Eisenhower—would make of Donald Trump as president today, or of the contagious verbal tic disorder that has become the broadcast norm, corrupting discourse and advancing group-think. It’s the oral analog of thoughtless writing, caused by three attitudes Steinbeck abhorred: haste, inattention, and lazy following.

Exceptions stand out because they’re both rare and promising at MSNBC. My favorite example is a young Washington Post opinion writer named Catherine Rampell, a frequent guest on Hardball with Chris Matthews and The Last Word, Lawrence O’Donnell’s marginally more listenable show in the slot behind Matthews, Hayes, and Maddow. As a communicator Catherine is like John Steinbeck: she speaks as she writes, clearly and carefully. I’m thrilled with her because she tickles my testy inner English teacher—and because I first met her when she was a high-achieving high school student in Palm Beach, Florida, where her father Richard Rampell, a culturally-attuned accountant, was my friend and fellow in the fight for local arts funding. In the past I’ve complained about Palm Beach, about the Trumpettes of Mar-a-Lago who worship Donald Trump and his dumbing down of everything. Now it’s a pleasure to praise the place for producing his opposite: a splendid writer and speaker with a career in journalism that John Steinbeck would admire and probably envy. Look for Catherine Rampell on MSNBC. And listen. You’ll be hearing about her.

Exceptions stand out because they’re both rare and promising at MSNBC. My favorite example is a young Washington Post opinion writer named Catherine Rampell, a frequent guest on Hardball with Chris Matthews and The Last Word, Lawrence O’Donnell’s marginally more listenable show in the slot behind Matthews, Hayes, and Maddow. As a communicator Catherine is like John Steinbeck: she speaks as she writes, clearly and carefully. I’m thrilled with her because she tickles my testy inner English teacher—and because I first met her when she was a high-achieving high school student in Palm Beach, Florida, where her father Richard Rampell, a culturally-attuned accountant, was my friend and fellow in the fight for local arts funding. In the past I’ve complained about Palm Beach, about the Trumpettes of Mar-a-Lago who worship Donald Trump and his dumbing down of everything. Now it’s a pleasure to praise the place for producing his opposite: a splendid writer and speaker with a career in journalism that John Steinbeck would admire and probably envy. Look for Catherine Rampell on MSNBC. And listen. You’ll be hearing about her.

Grammar-Check Your Blog Post About John Steinbeck

Though he occasionally misused or misspelled words, John Steinbeck wrote to be understood, often revising sentences, paragraphs, and whole chapters before publishing. Unfortunately, blog posts written about Steinbeck for online magazines, ostensibly with grammar-checking editors, frequently confuse readers with sentences so ill-considered that their meaning is unclear or absent. Recent examples of both errors in online writing about Steinbeck’s greatest fiction can be found in a pair of blog posts published by two online magazines that, except for sectarianism and under-editing, couldn’t be less alike.

How Did The Forward Get John Steinbeck So Wrong?

The first post in question is by Aviya Kushner, the so-called language columnist of The Forward, a respected Jewish publication started in New York five years before Steinbeck was born. The “news flash from the distant land of real news” on offer in Kushner’s May 8 blog post—“How Did John Steinbeck and an Obama Staffer Get the Bible So Wrong?”—is the misspelling of timshol in East of Eden, old news to Steinbeck fans of all faiths or no faith at all. Kushner’s charge—that Steinbeck’s spelling error was an offense against language, culture, and morality—is undermined by her syntax. “It comes down to caring about language,” she writes in conclusion, “and insisting that words have meaning, which is, frankly, a hot contemporary topic that is not just political but also moral.” Ouch and double ouch.

Faith Is No Excuse When Blog Posts Make No Sense

The second example of online magazines writing badly about John Steinbeck comes from Pantheon, a site that bills itself as “a home for godly good writing,” apparently without irony. “Dreaming of Steinbeck’s Country”—the May 6 blog post by a self-identified minister named James Ford—means well but also proves that sententious praise, like captious criticism, collapses when style fails subject in sentences describing Steinbeck. “I consider the Grapes of Wrath [sic] one of the great novels of our American heritage,” writes Ford. “Currents of spirituality and spiritual quest together with a progressive if increasingly that agnostic form of Christianity feature prominently in Steinbeck’s writings. And no doubt it informs his masterwork the Grapes of Wrath.” [Sic] and [sic] again.

Is Your Piece Ready to Publish, or Does It Escape?

The lesson to be learned from this week’s examples of bad online writing? When blogging about John Steinbeck, take time to spell- and syntax- and grammar-check before posting. Online magazines have editors, but contributed posts are like the morning newspaper in Florida whose editor I once overheard describe this way: “Our paper isn’t published. It escapes.” Websites with a sectarian purpose, like The Forward and Pantheon, often make the mistake of allowing sentiment to overwhelm sense when publishing blog posts by sincere writers with a pro or con ax to grind. Steinbeck agonized over The Grapes of Wrath. East of Eden took years to write. Travels with Charley didn’t, and it shows. Is taking time to self-edit when writing about John Steinbeck for any website, secular or religious, asking too much?

From Travels with Charley to 30 Days a Black Man: Review

30 Days a Black Man: The Forgotten Story That Exposed the Jim Crow South, a new book by Bill Steigerwald about Ray Sprigle, the white Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter who investigated race in America by passing through the South as a black man, is now in bookstores, including the airport shop shown in this photo. Like Steinbeck’s social fiction from the 1930s, Sprigle’s syndicated series on segregation in the South increased understanding when it appeared in 1948, but also met resistance. Steigerwald’s account of the controversy will hold particular appeal for Steinbeck fans familiar with the back story of The Grapes of Wrath, and for sympathetic readers of Travels with Charley, the 1962 work in which Steinbeck touched on Sprigle’s theme. The connections are compelling. Steigerwald is a former reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette who made the opposite transition from Steinbeck, from newspaper journalist to full-time book author, in his career as a writer. His first book, Dogging Steinbeck, exposed fictional elements in Steinbeck’s account of the picaresque journey that ends dramatically in New Orleans, where white mothers scream at black children and Steinbeck discusses desegregation with a trio of sample Southerners, real or imagined, who typify the racial divide exposed by Ray Sprigle more than a decade earlier.

Homeless Man in Central Florida Finds Body: Poem

Homeless Man Reports a Dead Body

by Carrying a Skull into a Florida Publix

—Colin Wolf, Orlando Weekly

Imagine him in the act of crossing busy US 1,

a silver shopping cart to slow the murmuration.

See the heat shimmers above the road surface.

See a Maserati swerve. Hear a Bentley brake

hard enough to make the muscles of the heart

speed up. In no time, he is parking the object

on a trash can by a double-door to a Publix.

By the pink-flamingo-themed lottery posters.

Why did he take it? Maybe the eyes called up

long rows of tombstones. His own dear dead

or their histories. One witness says he used it,

the skull, like a hand puppet. One said it stank.

Which is why cruisers pull up and spill a cargo

of sheriffs in their Ray Ban Aviator sunglasses.

Later that day, another part of the neighborhood,

a van is parked in drifts and mangroves bordering

a strip club. Under night-marching moon and stars,

the doorjamb of the van hemorrhages arterial-red,

the factory-painted truth that this rough home

is limbed with death in the best of weather.

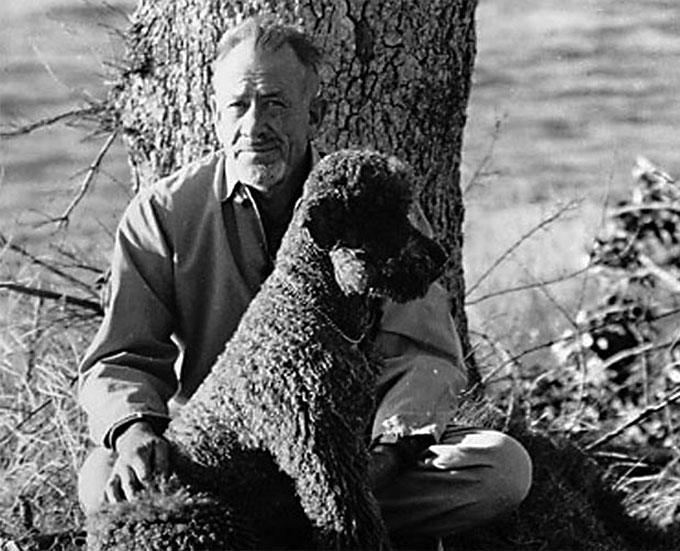

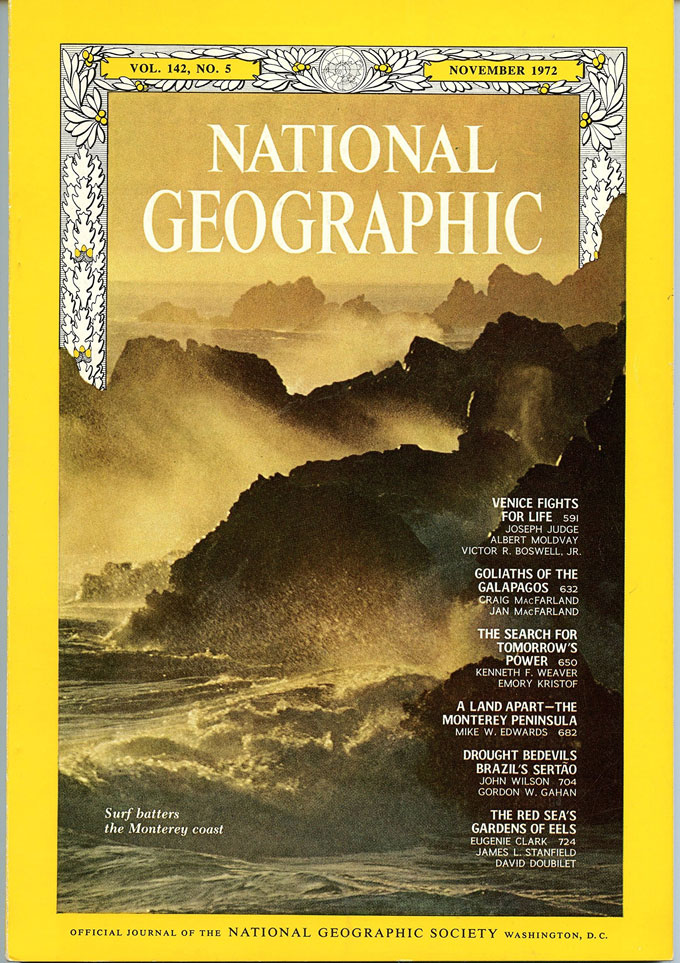

The Monterey Peninsula and John Steinbeck’s Myna Bird

Although I think he eventually changed his mind, in 1972 I was able to empathize with John Steinbeck’s dislike of being interviewed when a writer from National Geographic magazine came to California’s Monterey Peninsula to do a cover piece on the region. His name was Mike Edwards, and he phoned me to set up an interview. I had been a reporter for the Monterey Peninsula Herald, as it was called then, and had left there and was now working over the hill for the Carmel Pine Cone. Interviewing people was the same for both newspapers and I felt at ease with it. Being on the other side of the desk, being interviewed myself instead of doing the interviewing, seemed a natural, so I said yes when Mike called.

National Geographic Captured “Interesting Times” in 1972

These were interesting times in our region. The hippie movement was in full flux and kids were getting in trouble smoking weed and running away from Cleveland or Denver and hiding out from frantic parents on the Monterey Peninsula or down in Big Sur. I did a story for the Herald about a local mayor riding with the police to root out the hippies. The next day I encountered the mayor and, his eyes big, he said, “My God, that story you did on me—people are furious with me!’’ That reflects the way Monterey Peninsula people could be in those days. There was a lot of conservative money, yes, but most of the citizens believed in individual rights. They didn’t want a mayor to be a cop hassling hippies. When an oil company threatened to drill in Monterey Bay, protestors included hippies and others from the left, along with marchers from the right, joining in common cause. The oil company backed off.

These were interesting times in our region. The hippie movement was in full flux and kids were getting in trouble smoking weed and running away from Cleveland or Denver and hiding out from frantic parents on the Monterey Peninsula or down in Big Sur. I did a story for the Herald about a local mayor riding with the police to root out the hippies. The next day I encountered the mayor and, his eyes big, he said, “My God, that story you did on me—people are furious with me!’’ That reflects the way Monterey Peninsula people could be in those days. There was a lot of conservative money, yes, but most of the citizens believed in individual rights. They didn’t want a mayor to be a cop hassling hippies. When an oil company threatened to drill in Monterey Bay, protestors included hippies and others from the left, along with marchers from the right, joining in common cause. The oil company backed off.

When I met with Mike Edwards at my desk at the Pine Cone I was surprised to discover that, while interviewing others was easy, being interviewed made me uncomfortable. Though Mike was a gentleman, polite and professional, I was a nervous wreck. I was used to asking the questions, not answering them, and I was relieved when the November National Geographic appeared and I saw that Mike had been merciful. I was neither quoted nor mentioned in “A Land Apart – The Monterey Peninsula,’’ though I hoped I’d at least provided him with some decent background for his story.

Mike had come to the Monterey Peninsula deeply interested in the region through reading John Steinbeck. He wrote in his piece that he was drawn to the “derelict sheds – part corrugated metal, part masonry, part rusting clutter – that stand along the seven blocks of Cannery Row’’ by reading Cannery Row. Steinbeck’s friends Bruce and Jean Ariss helped him understand the area even more. The Arisses were on their way to becoming local legendary figures themselves, in part because of their friendship with Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, but also because they were talented artists of great strength and character. Bruce was a painter and writer. Jean was the author of two novels—The Quick Years and The Shattered Glass.

“Being Quotable” About the Title of The Grapes of Wrath

“I spent an interesting afternoon in the company of Jean,” Mike wrote, “and her husband, Bruce, a writer, editor, and artist well known for his murals,” explaining that “they saw Steinbeck often in Edward Ricketts’ laboratory on the Row.‘’ After describing Steinbeck as “a large, thickset man, usually wearing jeans and a shabby sheepskin coat,” Jean told Mike about spending a day in 1939 with John Steinbeck, his wife Carol, and Ed Ricketts, going over the manuscript of John’s new novel, not yet titled. “She remembers Ricketts saying to Steinbeck, ‘This is a fine book – your best. It will win you the Nobel Prize.’ . . . The group spent the afternoon trying to think of a title, finally agreeing on ‘The Grapes of Wrath.’ “

“I spent an interesting afternoon in the company of Jean,” Mike wrote, “and her husband, Bruce, a writer, editor, and artist well known for his murals,” explaining that “they saw Steinbeck often in Edward Ricketts’ laboratory on the Row.‘’ After describing Steinbeck as “a large, thickset man, usually wearing jeans and a shabby sheepskin coat,” Jean told Mike about spending a day in 1939 with John Steinbeck, his wife Carol, and Ed Ricketts, going over the manuscript of John’s new novel, not yet titled. “She remembers Ricketts saying to Steinbeck, ‘This is a fine book – your best. It will win you the Nobel Prize.’ . . . The group spent the afternoon trying to think of a title, finally agreeing on ‘The Grapes of Wrath.’ “

That’s what you call being quotable. John Steinbeck gave Carol credit for the title, so perhaps it was on the day Jean recalled in her interview with Mike Edwards. I wish Jean had been more specific. If she were, I’m sure Mike would have reported it. He went on to a distinguished career, writing 54 articles from around the world for National Geographic. He was honored by the Foreign Correspondents Association for his writing on the nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl—something Steinbeck would have admired, the courage to cover that story—and he retired as a senior editor at National Geographic in 2002. He died last year in Arlington, Virginia.

Why do I think John Steinbeck eventually changed his mind about being interviewed? Because of a collection of 26 articles, all quoting Steinbeck, titled Conversations with John Steinbeck, edited by Thomas Fensch and published by the University of Mississippi. At times Steinbeck comes across as taciturn and uncooperative. At others he really seems to be enjoying himself. My wife Nancy and I picked up a copy several years ago in a little shop on Lighthouse Avenue in New Monterey, which used to have a half-dozen bookstores specializing in collectible editions. At the time I was working on a play about Steinbeck, setting him in his New York apartment at night, the only other characters a ghost, a talking myna bird, and a whirring tape recorder.

Why do I think John Steinbeck eventually changed his mind about being interviewed? Because of a collection of 26 articles, all quoting Steinbeck, titled Conversations with John Steinbeck, edited by Thomas Fensch and published by the University of Mississippi. At times Steinbeck comes across as taciturn and uncooperative. At others he really seems to be enjoying himself. My wife Nancy and I picked up a copy several years ago in a little shop on Lighthouse Avenue in New Monterey, which used to have a half-dozen bookstores specializing in collectible editions. At the time I was working on a play about Steinbeck, setting him in his New York apartment at night, the only other characters a ghost, a talking myna bird, and a whirring tape recorder.

I got the idea for the myna bird from a Steinbeck letter I traded for some years ago, a handwritten missive to Fred Zinnemann, the director of High Noon, From Here to Eternity, and other fine films. In the letter Steinbeck is giving the myna bird to Zinneman, and describes the bird’s character and required care. The tape recorder in the play was, I think (one can never be quite sure about these things) my own invention, perhaps inspired by reading that Steinbeck liked tinkering and “gadgets.”

The Imaginary Myna Bird With the Meaningful Name

Nancy and I took Conversations with John Steinbeck home, sat down on the couch, and opened it. One of the first interviews we read was a 1952 piece by New York Times drama critic Lewis Nichols interviewing Steinbeck in the author’s Manhattan apartment. They seemed to get along well as Steinbeck discussed work on the book that would become East of Eden. Steinbeck proudly mentioned having a writing room, something that—echoing Virginia Woolf—he considered of paramount importance. “This,” Nichols wrote, “is the first room of his own he ever has had.’’ Then: “It is a very quiet room. For companionship, Mr. Steinbeck would like to get a myna bird. With a tape recorder he would teach this to ask questions, never answer, just ask.’’

When we read that, Nancy looked at me and we laughed. We felt we were channeling John Steinbeck, though to this day I still haven’t finished the play. Neither have I given up. Someday. And someday I’d like to elaborate on Steinbeck’s charming myna bird letter to Zinnemann. Steinbeck, incidentally, called the myna bird “John L.”

When we read that, Nancy looked at me and we laughed. We felt we were channeling John Steinbeck, though to this day I still haven’t finished the play. Neither have I given up. Someday. And someday I’d like to elaborate on Steinbeck’s charming myna bird letter to Zinnemann. Steinbeck, incidentally, called the myna bird “John L.”

For the fighter John L. Sullivan? Or the labor leader John L. Lewis? Either one would be meaningful.