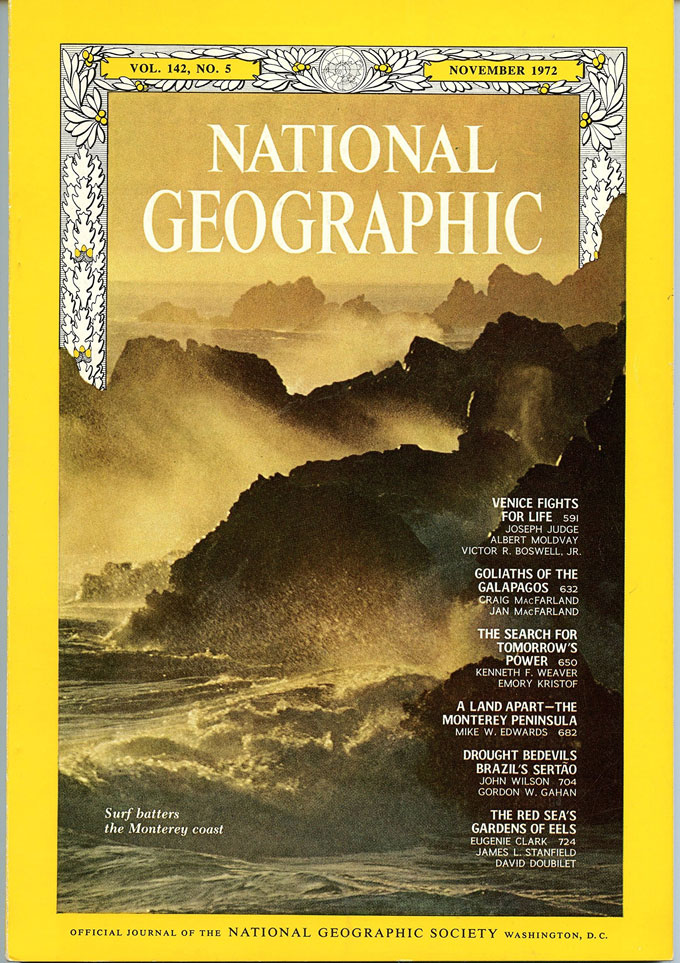

Although I think he eventually changed his mind, in 1972 I was able to empathize with John Steinbeck’s dislike of being interviewed when a writer from National Geographic magazine came to California’s Monterey Peninsula to do a cover piece on the region. His name was Mike Edwards, and he phoned me to set up an interview. I had been a reporter for the Monterey Peninsula Herald, as it was called then, and had left there and was now working over the hill for the Carmel Pine Cone. Interviewing people was the same for both newspapers and I felt at ease with it. Being on the other side of the desk, being interviewed myself instead of doing the interviewing, seemed a natural, so I said yes when Mike called.

National Geographic Captured “Interesting Times” in 1972

These were interesting times in our region. The hippie movement was in full flux and kids were getting in trouble smoking weed and running away from Cleveland or Denver and hiding out from frantic parents on the Monterey Peninsula or down in Big Sur. I did a story for the Herald about a local mayor riding with the police to root out the hippies. The next day I encountered the mayor and, his eyes big, he said, “My God, that story you did on me—people are furious with me!’’ That reflects the way Monterey Peninsula people could be in those days. There was a lot of conservative money, yes, but most of the citizens believed in individual rights. They didn’t want a mayor to be a cop hassling hippies. When an oil company threatened to drill in Monterey Bay, protestors included hippies and others from the left, along with marchers from the right, joining in common cause. The oil company backed off.

These were interesting times in our region. The hippie movement was in full flux and kids were getting in trouble smoking weed and running away from Cleveland or Denver and hiding out from frantic parents on the Monterey Peninsula or down in Big Sur. I did a story for the Herald about a local mayor riding with the police to root out the hippies. The next day I encountered the mayor and, his eyes big, he said, “My God, that story you did on me—people are furious with me!’’ That reflects the way Monterey Peninsula people could be in those days. There was a lot of conservative money, yes, but most of the citizens believed in individual rights. They didn’t want a mayor to be a cop hassling hippies. When an oil company threatened to drill in Monterey Bay, protestors included hippies and others from the left, along with marchers from the right, joining in common cause. The oil company backed off.

When I met with Mike Edwards at my desk at the Pine Cone I was surprised to discover that, while interviewing others was easy, being interviewed made me uncomfortable. Though Mike was a gentleman, polite and professional, I was a nervous wreck. I was used to asking the questions, not answering them, and I was relieved when the November National Geographic appeared and I saw that Mike had been merciful. I was neither quoted nor mentioned in “A Land Apart – The Monterey Peninsula,’’ though I hoped I’d at least provided him with some decent background for his story.

Mike had come to the Monterey Peninsula deeply interested in the region through reading John Steinbeck. He wrote in his piece that he was drawn to the “derelict sheds – part corrugated metal, part masonry, part rusting clutter – that stand along the seven blocks of Cannery Row’’ by reading Cannery Row. Steinbeck’s friends Bruce and Jean Ariss helped him understand the area even more. The Arisses were on their way to becoming local legendary figures themselves, in part because of their friendship with Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts, but also because they were talented artists of great strength and character. Bruce was a painter and writer. Jean was the author of two novels—The Quick Years and The Shattered Glass.

“Being Quotable” About the Title of The Grapes of Wrath

“I spent an interesting afternoon in the company of Jean,” Mike wrote, “and her husband, Bruce, a writer, editor, and artist well known for his murals,” explaining that “they saw Steinbeck often in Edward Ricketts’ laboratory on the Row.‘’ After describing Steinbeck as “a large, thickset man, usually wearing jeans and a shabby sheepskin coat,” Jean told Mike about spending a day in 1939 with John Steinbeck, his wife Carol, and Ed Ricketts, going over the manuscript of John’s new novel, not yet titled. “She remembers Ricketts saying to Steinbeck, ‘This is a fine book – your best. It will win you the Nobel Prize.’ . . . The group spent the afternoon trying to think of a title, finally agreeing on ‘The Grapes of Wrath.’ “

“I spent an interesting afternoon in the company of Jean,” Mike wrote, “and her husband, Bruce, a writer, editor, and artist well known for his murals,” explaining that “they saw Steinbeck often in Edward Ricketts’ laboratory on the Row.‘’ After describing Steinbeck as “a large, thickset man, usually wearing jeans and a shabby sheepskin coat,” Jean told Mike about spending a day in 1939 with John Steinbeck, his wife Carol, and Ed Ricketts, going over the manuscript of John’s new novel, not yet titled. “She remembers Ricketts saying to Steinbeck, ‘This is a fine book – your best. It will win you the Nobel Prize.’ . . . The group spent the afternoon trying to think of a title, finally agreeing on ‘The Grapes of Wrath.’ “

That’s what you call being quotable. John Steinbeck gave Carol credit for the title, so perhaps it was on the day Jean recalled in her interview with Mike Edwards. I wish Jean had been more specific. If she were, I’m sure Mike would have reported it. He went on to a distinguished career, writing 54 articles from around the world for National Geographic. He was honored by the Foreign Correspondents Association for his writing on the nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl—something Steinbeck would have admired, the courage to cover that story—and he retired as a senior editor at National Geographic in 2002. He died last year in Arlington, Virginia.

Why do I think John Steinbeck eventually changed his mind about being interviewed? Because of a collection of 26 articles, all quoting Steinbeck, titled Conversations with John Steinbeck, edited by Thomas Fensch and published by the University of Mississippi. At times Steinbeck comes across as taciturn and uncooperative. At others he really seems to be enjoying himself. My wife Nancy and I picked up a copy several years ago in a little shop on Lighthouse Avenue in New Monterey, which used to have a half-dozen bookstores specializing in collectible editions. At the time I was working on a play about Steinbeck, setting him in his New York apartment at night, the only other characters a ghost, a talking myna bird, and a whirring tape recorder.

Why do I think John Steinbeck eventually changed his mind about being interviewed? Because of a collection of 26 articles, all quoting Steinbeck, titled Conversations with John Steinbeck, edited by Thomas Fensch and published by the University of Mississippi. At times Steinbeck comes across as taciturn and uncooperative. At others he really seems to be enjoying himself. My wife Nancy and I picked up a copy several years ago in a little shop on Lighthouse Avenue in New Monterey, which used to have a half-dozen bookstores specializing in collectible editions. At the time I was working on a play about Steinbeck, setting him in his New York apartment at night, the only other characters a ghost, a talking myna bird, and a whirring tape recorder.

I got the idea for the myna bird from a Steinbeck letter I traded for some years ago, a handwritten missive to Fred Zinnemann, the director of High Noon, From Here to Eternity, and other fine films. In the letter Steinbeck is giving the myna bird to Zinneman, and describes the bird’s character and required care. The tape recorder in the play was, I think (one can never be quite sure about these things) my own invention, perhaps inspired by reading that Steinbeck liked tinkering and “gadgets.”

The Imaginary Myna Bird With the Meaningful Name

Nancy and I took Conversations with John Steinbeck home, sat down on the couch, and opened it. One of the first interviews we read was a 1952 piece by New York Times drama critic Lewis Nichols interviewing Steinbeck in the author’s Manhattan apartment. They seemed to get along well as Steinbeck discussed work on the book that would become East of Eden. Steinbeck proudly mentioned having a writing room, something that—echoing Virginia Woolf—he considered of paramount importance. “This,” Nichols wrote, “is the first room of his own he ever has had.’’ Then: “It is a very quiet room. For companionship, Mr. Steinbeck would like to get a myna bird. With a tape recorder he would teach this to ask questions, never answer, just ask.’’

When we read that, Nancy looked at me and we laughed. We felt we were channeling John Steinbeck, though to this day I still haven’t finished the play. Neither have I given up. Someday. And someday I’d like to elaborate on Steinbeck’s charming myna bird letter to Zinnemann. Steinbeck, incidentally, called the myna bird “John L.”

When we read that, Nancy looked at me and we laughed. We felt we were channeling John Steinbeck, though to this day I still haven’t finished the play. Neither have I given up. Someday. And someday I’d like to elaborate on Steinbeck’s charming myna bird letter to Zinnemann. Steinbeck, incidentally, called the myna bird “John L.”

For the fighter John L. Sullivan? Or the labor leader John L. Lewis? Either one would be meaningful.

Here are two examples that Steinbeck did use a recording device:

I write longhand and then I read on tape and listen back. … I’ve tried reading aloud but then my eyes are involved. I read on tape and list back for corrections, because you can hear the most terrible things you’ve done if you hear it clear back on tape I do it particularly with dialogue because then I can find whether it sounds like speech or not.

– Conversations with John Steinbeck. Books & Bookmen, 1958, 67/8

I am enclosing my first draft of a part of the story which is titled Bourbon on the Rocks. If it is too much of a struggle to read, don’t bother with it but simply file it. I am sending off the belts [dictation] for typing … I just thought this might give you a little fun over weekend.

– Letters to Elizabeth. 3/14/56, p. 67.

Herb,

thanks. Love getting more information, especially in how he worked. I have him reading to a tape recorder at the beginning of the story “The Gaunt Visitor.” Then trying to record a ghost!

Steve

Steve:

Steinbeck donated his Dictaphone “belts” to the Morgan Library in NY. I can not tell from their catalogue if they transferred them to tape. They mention 3 of the 24 he donated, were put on tape The entry in their catalogue is rather confusing. They do not make clear what is actually on the tapes.

Herb

It could be important material. A research project for someone in NY.

Thanks Steve for a great story and loads of insights. I would bet on John L. Lewis for the name of the myna bird.

Lewis would have been someone Steinbeck would have admired for his courage and stance. Of course, Sullivan certainly didn’t lack courage. He began fighting bare knuckles.

Nice piece, Steve.

Paul, appreciate you taking the time to read and comment on it. Thanks.

This piece by Steve–and its comment exchanges with Herb Behrens and James Kent–has me feeling I’m “sitting in” on the kind of observations and exchanges that must have gone on in Pacific Biological Laboratories with similar spirits orbiting around Ed Ricketts, especially–but not exclusively–John’s. Also the comfort of learning a few more facets from them I probably would not have found on my own about the genius that left us so much to ponder and appreciate long after he’s gone. Thank you, gentlemen for this easy pleasure.

Michael,

intersting observations. There will always be that feeling around the lab I hope. I remember talking to a high school teacher years ago who said she took some students in, a couple of the lab guys who were still with us showed the kids around, and the next day the students “wrote wonderful papers about it.” I hope that can still happen.