Just the other day she stepped into our Pacific Grove, California gallery with a distinguished-looking gentleman who likes to do carvings. Her name’s Joy and the gentleman was her husband Jerry.

The subject of John Steinbeck came up—as it usually does in the gallery—and Joy said:

“My parents couldn’t stand him.”

“Why not?”

“They’d get late night phone calls from people, usually inebriated, asking for him—for John Steinbeck. Getting them up in the middle of the night infuriated my folks.”

Steinbeck probably would have liked Joy, a school teacher and administrator who has taught and teaches everything from English and business to quilting, because she added with finality: “And that’s all I know about it.”

It reminded me of something Ma Joad might say.

I waited a bit then asked some questions anyway.

Joy said her parents came to Pacific Grove in 1943. Her father was about 37 years old at the time but could have been drafted into the army even though he and his wife Lela had a young child. Someone recommended that he join the post office instead of the army and he did, becoming, eventually, a clerk in the Pacific Grove branch on Lighthouse Avenue, a branch Steinbeck would have used for many of his postal needs in the 1930s—perhaps sending off typescript copies of Tortilla Flat and Of Mice and Men to his publisher in New York.

What, I asked Joy, was her parents’ last name?

“Steinecke,” she said. “It came right after Steinbeck in the phone book.”

“And what was your father’s first name?’

“John,” she said.

It was beginning to come together . . . .

I could see someone in a phone booth looking up the Steinbeck phone number in the middle of the night—maybe to give the author some good advice, not realizing he was now living on the East Coast. Having had a few drinks, the caller could easily morph Steinbeck into Steinecke, or maybe the finger marking the place slipped down the page just a smidge and, hey, it still says John! If the Steinbeck name wasn’t listed, Steinecke would do nicely.

As a result, Mr. Steinecke, scheduled to begin work at the post office in a few hours, gets calls at two, three in the morning. Not easy to get back to sleep, the phone conversations likely still echoing in his head:

“Mr. Steinbeck, I think . . . I think you should change the ending of Tortilla Flat.“

“I’m a postal clerk!”

“I know, but you wrote the book.”

According to Joy, John Steinecke would not have been amused.

“My dad was the grandson of a Prussian general who immigrated from Germany in the mid-1800s,” Joy said. “His sense of humor was not particularly well-developed, and he would probably huff about those phone calls if he were still alive. Anyway, he might not laugh, but he definitely would be pleased that you were writing about him and John Steinbeck.”

So, on a recent morning, with images of John Steinbeck and John Steinecke dancing interchangeably in my head, I went into the Pacific Grove post office for stamps and spoke with a clerk named Ron. For all I know, Ron was standing where Mr. Steinecke stood decades ago.

Ron said, quite the opposite of what Mr. Steinecke thought in the 1940s, “Steinbeck’s one of my favorites. People recommend other writers, but I always seem to come back to Steinbeck.”

Of course, if Ron had been living back then, working in the Pacific Grove post office, and his name was John Steinecke, even Ron Steinecke, he might have switched his literary allegiance to Hemingway or Faulkner.

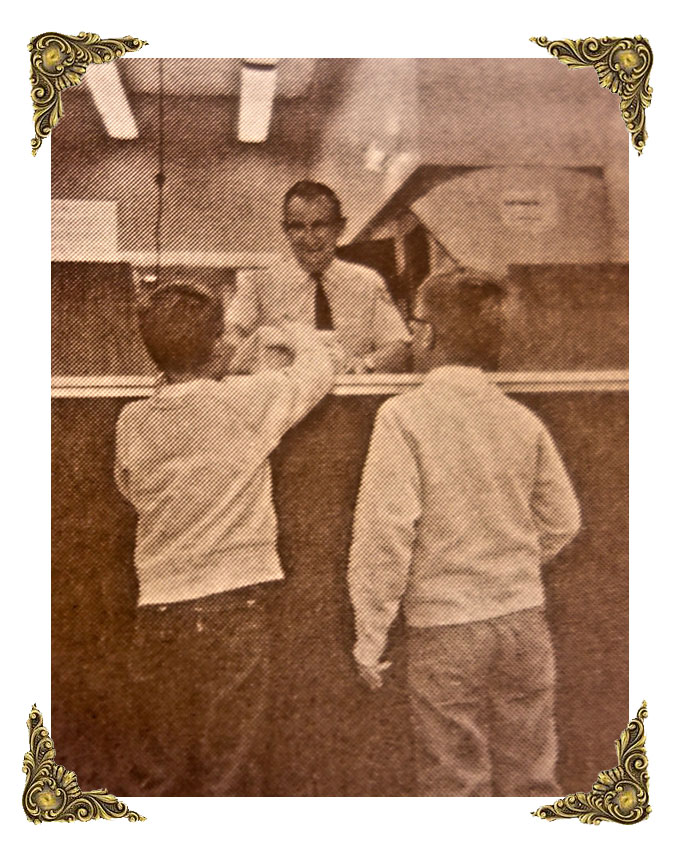

Period photo of John Steinecke serving young customers at the Pacific Grove post office from Norton and Gus, by Margaret Hayden Rector (Grossmont Press, 1976).

This is really funny Steve. Thanks for posting

As a man with a last name of Miller (Muller only four generations ago) I can sympathize with poor Mr. Steinecke. My great-great grandfather may have been in the same Prussian army and passed on the gene. Postal clerks, barbers, gallery owners–these are people you can talk to or listen to–they always have great stories.

Thanks Steve.