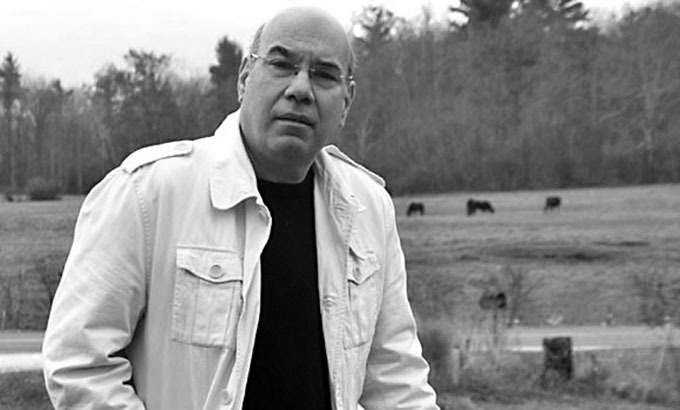

John Steinbeck studied Pilgrim’s Progress at his mother’s knee. Literally. John Bunyon’s allegory of sin and salvation was still family reading when Olive Steinbeck taught her pre-school son the alphabet 100 years ago and home libraries like the Steinbecks’ had books like Pilgrim’s Progress, so essential to Christian living that they were read aloud at family gatherings like the Bible. Like his father, John Steinbeck was often depressed about life, and Bunyon’s Slough of Despond colored his dark view of home town Salinas, a place of sloughs in both senses of Bunyon’s word—“swampy” and “characterized by lack of progress.” Like his mother, he had conflicting views about religion, “a curious mixture [for her, he said] of Irish fairies and an Old Testament Jehovah.” Her parents were frontier Calvinists, but she sent her son to the Episcopal church, where he stayed, nominally, until he died. He told his physician that he didn’t believe in an afterlife, but he wanted an Episcopal church funeral anyway and his fiction is full of religion gleaned from books he read in childhood—the Bible, Pilgrim’s Progress—and mined for material in books still read today. Fortunately for readers without grounding in Steinbeck’s religion, Steinbeck’s biographer Jay Parini (in photo) has provided a Pilgrim’s Progress for the post-Christian century in The Way of Jesus, a spiritual autobiography by a gifted writer that also serves as a reader’s guide to Christianity in the spirit of Steinbeck’s fiction—progressive, companionable, and inviting participation.

The Way of Jesus: A Better Way to Understand Belief

Like John Steinbeck, Jay Parini found refuge in the Episcopal church from the fundamentalism of puritanical forebears. Like William Faulkner and Gore Vidal, authors whose lives he chronicled after writing about Steinbeck, Parini is a working novelist with a foot in the film world and—like Robert Frost, another subject—a people’s poet with a Vermonter’s view of America. He teaches creative writing at Middlebury College, and The Way of Jesus is a teaching book with all the traits of a well-taught course. A second-semester sequel to Parini’s life of Jesus with a literary approach to scripture and belief, it explores the poetry of T.S. Eliot and the aggregation of writings we call the Bible with equal agility. Designed for readers without special knowledge, its explanation of esoteric topics like Christian liturgy, Calvinist theology, and the church year—features of Steinbeck’s fiction from Tortilla Flat to The Winter of Our Discontent—is abundantly clear and courteous to newcomers. The ease and efficiency will appeal to students, and the extra equipment, including source documentation, will please their professors. Happiest of all will be fans of literature (if not religion) who love somebody else’s story when it involves them and invites action, like Steinbeck at this best.

Like John Steinbeck, Jay Parini found refuge in the Episcopal church from the fundamentalism of puritanical forebears. Like William Faulkner and Gore Vidal, authors whose lives he chronicled after writing about Steinbeck, Parini is a working novelist with a foot in the film world and—like Robert Frost, another subject—a people’s poet with a Vermonter’s view of America. He teaches creative writing at Middlebury College, and The Way of Jesus is a teaching book with all the traits of a well-taught course. A second-semester sequel to Parini’s life of Jesus with a literary approach to scripture and belief, it explores the poetry of T.S. Eliot and the aggregation of writings we call the Bible with equal agility. Designed for readers without special knowledge, its explanation of esoteric topics like Christian liturgy, Calvinist theology, and the church year—features of Steinbeck’s fiction from Tortilla Flat to The Winter of Our Discontent—is abundantly clear and courteous to newcomers. The ease and efficiency will appeal to students, and the extra equipment, including source documentation, will please their professors. Happiest of all will be fans of literature (if not religion) who love somebody else’s story when it involves them and invites action, like Steinbeck at this best.

I respectfully disagree with the theories and conclusions of this article. In my opinion, the reason Steinbeck was buried as an Episcopalian was out of love and deep respect for his mother who was on the Altar Guild of the Salinas Episcopal church. I do not believe he completely embraced the (Nicene) creed of the Episcopal, Anglican, or any other Christian church. His relationship with God was similar to that of Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, and George Washington. John Steinbeck was a non-teleological, cognitive Gnostic. Privately he would not embrace any religion that demands unquestioned acceptance of dogma or doctrine. He would resent any demand that you leave your brains at the door of the sanctuary. Didn’t he and Ed Ricketts visit the local Monterey Unitarian Universalist congregation one time? His covenant with his God was as unique as his intellect. “I am a sect of one.”–Thomas Jefferson.

Thanks Wes, insightful as usual. I agree with you. There is evidence throughout Steinbeck’s writings that he would not be a member of any church. A psychological impossibility. For instance from East of Eden i find a statement that the Unitarians would love to own: “An this I believe: that the free, exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world. And this I would fight for: the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any idea, RELIGION, or government which limits or destroys the individual. This is what I am and what I am about.” Amen to that!

Also one of my favorites from The Grapes of Wrath:” There ain’t no sin and there ain’t no virtue: There’s just stuff people do.” Sounds a lot like Ed Ricketts “is” theory.

Thanks Jim, Love the response. As usual you are on themark.

Wes