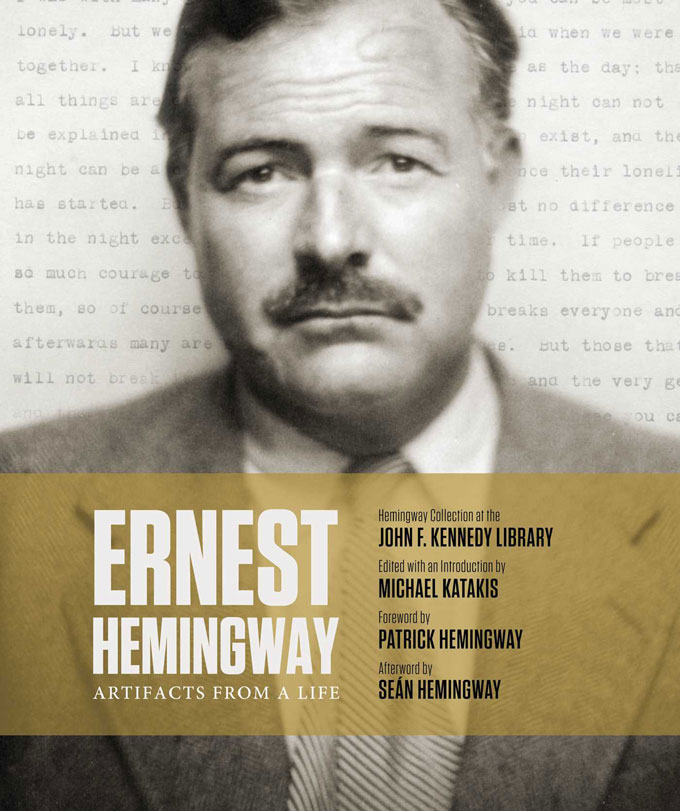

If a photo had been taken of Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck when they met for the first and only time, at Tim Costello’s restaurant in New York in 1944, Michael Katakis would know, and he would have shared it with us in the visual biography that puts a fresh face on an old legend: Ernest Hemingway: Artifacts from a Life, a life story in pictures, with connecting word tissue, drawn from the Hemingway collection at the Kennedy Library, edited with an introduction by Michael, who has served as the executor of Hemingway’s literary estate since 1999. A writer and documentary photographer, he manages to divide his time productively between Paris, Hemingway’s city, and Steinbeck’s Carmel, California, a distance that symbolizes the divide experienced by the two writers in the 1920s, and the difference in attitude each took toward other writers in the decades that followed. Steinbeck, more sympathetic and less assertive, admired Hemingway and showed respect. That Hemingway behaved otherwise is apparent in the account of the 1944 meeting written in 1989 by Jackson Benson, author of the 1984 best-seller, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer. The achievement of Ernest Hemingway: Artifacts from a Life in using archival material to reframe and restore Hemingway’s reputation in 2018 raises another issue regarding Steinbeck. Libraries at various locations hold an abundance of artifacts—family photographs, private correspondence, personal memorabilia—from Steinbeck’s life. Fifty years after his death, are his executors, editors, and heirs too distant, or too divided, to do the same thing for him?

Archives for November 2018

Sag Harbor Library Returns John Steinbeck’s Love

When John Steinbeck and his wife Elaine bought a home in Sag Harbor, New York in 1955, the whaling village on the eastern tip of Long Island had the essential ingredients for happiness the controversial writer missed after leaving Pacific Grove, California—water, history, and a casual lifestyle, like Cannery Row, that allowed for anonymity. New England whaling had gone the way of the California sardine industry long before the couple’s arrival, but weekend fishing was still good and a Sag Harbor tradition of hospitality to authors, starting with James Fenimore Cooper, survived. That particular tradition is on display again through December 20, 2018, the 50th anniversary of John Steinbeck’s death, with a commemoration of Steinbeck’s life by Sag Harbor’s John Jermain public library, named after a local hero from Cooper’s time. Activities include films, library talks, and a digital wall of remembrance for residents who knew or saw Steinbeck when he and Elaine were in town. (Catherine Creedon, the library director, is shown with Preservation Long Island award recipient Zach Studenroth in this April 11, 2018 photograph by Michael Heller, courtesy of the Sag Harbor Express.)

Finding Solace from Vladimir Putin and Trump in Steinbeck

Donald Trump said weather kept him from wreath-laying duty at the American cemetery outside Paris on the 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended the Great War. But the rain-shy Make-America-Great-Again president managed to keep his Armistice Day date in Paris with Vladimir Putin, the former KGB officer who runs Russia the way Stalin did when John Steinbeck and Robert Capa toured the Soviet Union 70 years ago. Previously undisclosed details of KGB spying on Steinbeck and Capa emerged from a recently declassified document summarized in a Radio Free Europe report that should stir anyone anxious about Russian history repeating itself in the love affair between Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump. (For a dose of relief, see Stephen Cooper’s blog post on finding solace in Steinbeck published by The Hill in 2016.)

East Meets West in the Illustrations for Tortilla Flat

A number of years ago an art dealer on the East Coast called me in Pacific Grove, California to say he had access to the original illustrations commissioned by Viking Press for the deluxe edition of Tortilla Flat. Would I be interested in buying? I found a copy of the 1935 novel that gave Steinbeck his first dose of security, glanced at the illustrations for the 1947 edition, and promptly phoned the dealer. I liked Steinbeck’s fiction, but I had no clue that I would write a book of stories about him. It was the art dealer and lover of art who said yes that afternoon. The illustrations for Tortilla Flat, by an artist named Peggy Worthington, were exquisite.

The inside cover flap of the book was sketchy about her life but accurate in explaining how well illustrations mirrored Steinbeck’s colorful text: “For this new edition, Peggy Worthington, the artist, has done seventeen paintings in oil, here glowingly reproduced as full color illustrations and jacket. She spent much time in Monterey, and has admirably captured the atmosphere of both the setting and the kind of people of whom Steinbeck wrote. The strong, primary, human quality of the story is expressed in her paintings, and the result is a thoroughly handsome book to give and to own.”

When I asked the dealer for information, he said that Peggy was an East Coast artist who was rumored to have been a student of Norman Rockwell, the most celebrated illustrator of 20th century. He added that she might also be known as Peggy Worthington Best, for she was married to Marshall Best, a senior editor at Viking.

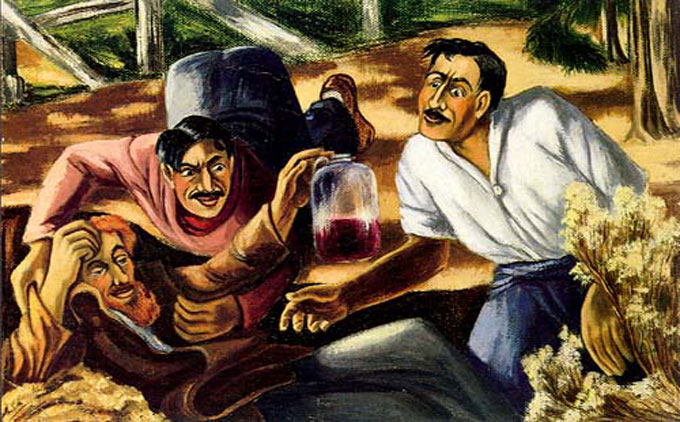

It wouldn’t have been surprising if she got the commission through her husband. Best is mentioned several times in Jackson Benson’s biography of Steinbeck, though the editor and the author weren’t close. Steinbeck’s editor at Viking, Pat Covici, was caught in the middle when conflict occurred, and Best was Covici’s boss. Peggy Worthington Best didn’t appear in Benson’s book, or anywhere else that I looked, but I bought two of the illustrations anyway. One shows Jesus Maria Corcoran polishing off a jug of wine, to the dismay of Pilon and Pablo. The other depicts Danny and Dolores in conversation over a picket fence. I wish I could have bought more, but money was tight and the price wasn’t cheap.

Both of the pieces I bought were included in the 1998 inaugural art exhibition of the National Steinbeck Center: This Side of Eden – Images of Steinbeck’s California, which I co-curated with Patricia Leach. From the Steinbeck Center in Salinas the show traveled to the Laguna Art Museum, accompanied by a brilliantly designed catalog by Melissa Thoeny and Glenn Johnson. The exhibition put our gallery on the map of Steinbeck’s California, and people started bringing in Steinbeck-related material—not just artwork, but letters and other important documents as well.

All of this eventually led to the book of short stories about Steinbeck’s life that I wrote and Steinbeck Books published in 2017. In 2008 we had created an exhibition featuring material brought in since 1998, along with the two illustrations from Tortilla Flat and other Steinbeck-related works of art. The title suggested by our friend Chris Carroll for the show—Steinbeck: Armed with the Truth—played on the idea of weaponry the way Steinbeck did when he wrote to a struggling novelist with the advice that “your only weapon is your work.” As in 1998, the show attracted a lot of attention. I still have Peggy’s picture of Danny and Dolores, but a buyer offered more than I could refuse for Jesus Maria, Pilon, and Pablo.

My curiosity about Peggy Worthington Best came to mind recently when I ran across collector copies of Tortilla Flat for sale online. Recalling the 1947 book blurb (“She spent much time in Monterey, and has captured the atmosphere of both the setting and the kind of people Steinbeck wrote of”), I realized how fully her art justified the praise. The clouds gathering over San Carlos Cathedral in one illustration, the mist drifting through the Monterey pines as the Pirate lectures his dogs, Danny and Dolores in front of her white board-and-batten cottage, so typical of Monterey and Pacific Grove past and present—everything looks seen.

Peggy must have kept a low profile when she visited. Assuming she came at or around the time of the Tortilla Flat commission, it’s possible that she (and perhaps her husband—though Benson doesn’t mention it) were hosted or helped by the author of the book she was illustrating. Less speculative than an encounter with Steinbeck in California is her relationship with an artist of equal stature in Massachusetts. This came to light recently, when a letter dated September 28 of 1961, addressed to “Peggy Worthington Best, Stockbridge,” came up for sale. The part quoted in the ad has the bones of a story by O. Henry: “Dear Peggy, since we are such good friends I just don’t want the news to reach you second hand. Molly Punderson and I are going to be married. I guess everyone in town will probably know this before long. I know you’ll be pleased for me.”

The seller of the letter in question is asking $1,000. A note to Peggy from the letter’s author sold for $250 or so some years ago. He had taken classes from Peggy in Stockbridge or Cambridge (versions differ) because his art had become tight and he wanted to loosen up. And he often sketched with Peggy. Who was the note-writer who wanted to brush up on his technique with the illustrator of Tortilla Flat? His name was Norman Rockwell . . . and he studied with her, not the other way around. Peggy Worthington may have been an East Coast artist, but East meets West in her work. Through it she came into contact with great artists on both coasts, including Norman Rockwell and John Steinbeck. Given time, who knows what other names will emerge.