I first read Steinbeck in high school. The book was Of Mice and Men, and I still remember how I felt when I finished. Lennie’s death was sad, but the final scene struck me as both necessary and beautiful, though I had yet to explore the paradox it presented. My world was black and white, filled with the naive explanations and simple solutions of boyhood. It had no room for ambivalence or complexity. Lennie was going to hang. George had no choice. What was I supposed to make of that at the age of 15?

Lennie was going to hang. George had no choice. What was I supposed to make of that at 15?

As my understanding of life and literature matured, I learned that philosophical questions lurked behind the emotional ending of Steinbeck’s novella-play. Was George justified in killing Lennie? What is justice? And who is the judge? What is the right response to a broken world? Above all, is there hope for healing? Spurred by these questions, I went on to discover subterranean levels of meaning in Steinbeck’s longer fiction, particularly in East of Eden, where the conflict of good and evil is clear but also complicated.

The Road from “Of Mice and Men” to “East of Eden”

“I believe that there is one story in the world, and only one,” Steinbeck wrote in the novel. “Humans are caught . . . in a net of good and evil . . . . There is no other story.” The moral dichotomy laid out by Steinbeck is simple in concept, but the narrative iterations in which it appears are endless. Steinbeck, whose world was never black and white, expressed this complexity throughout his work. He recognized the danger posed by the utopian revolutionary and the reactionary cynic alike, each attached to a false premise of possible permanence. Instead of certainty he sought balance, truthful balance, and he knew that relativity and change are rules imposed by nature.

Steinbeck, whose world was never black and white, expressed this complexity throughout his work.

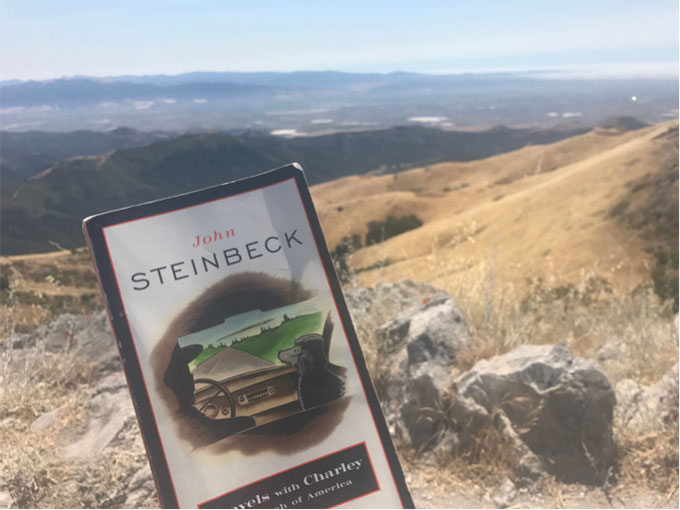

An avid observer of marine life, Steinbeck writes like the changing tides, never claiming to know where one wave ends and another begins. Instead, he contemplates water hitting the shore and the adaptation required of all creatures to survive the shock, inviting readers to consider the process and the results. After Of Mice and Men, I began to appreciate the confounding complexity of existence and the responsibility of the individual to uncover meaning which Steinbeck embraced in his writing. “He’ll take from my book what he can bring to it,” Steinbeck said of his readers in a note to Pat Covici, his editor. “The dull witted will get dullness and the brilliant may find things in my book I didn’t know were there.” Steinbeck had done his part. Now, it was my turn to drive.

Steinbeck had done his part. Now it was my turn to drive.

Six years after first reading Of Mice and Men, I keep coming back to Steinbeck with a perspective that, if not brilliant, is deeper than that of high school. His work has not changed, but my understanding and appreciation have, and I’m writing fiction of my own. I’ve abandoned the passive interpretations of youth for the active ambiguity of adulthood, as Steinbeck had done at my age. Like Steinbeck and Ricketts searching the Pacific tide pools, I look below the surface of the prose I encounter and create, combing for balance and truth in the shifting sand.

Thank you for sharing a classical “turn.”

Dear Carter Davis Johnson:

Why in the world would you want to be a military cadet? I am a Vietnam combat veteran and I had THOUGHT I fought in the last of America’s Bad Wars. Silly me! With the on-going wars in Afghanistan and Iraq— combined with the conflict in Syria and our shameful involvement in the Yemeni civil war— we are faced with the prospect of endless war; and the ever expanding military budget that entails; and the resulting crumbling of our funding of other, vital civilian needs.

P.S.: I am the author of “The Combined Action Platoons: The U.S.Marines Other War in Vietnam.” (Praeger Press: 1989).

An enjoyable, insightful piece. I hope Mr. Johnson gets out here one day to experience our gentle, shimmering with life Pacific Grove tide pools. Steinbeck wrote to his friend Toby Street that walking by them was “a good way to get back a sense of proportion.”

Like Gone with the Wind, books are the best. So much more is fleshed out.

Like a book going into film, Gary Sinise’s film Of Mice and Men is the best. I wish Steinbeck had lived to see it.