Seventeen or 18 years ago, maybe longer, the artist Judith Deim faxed me a long handwritten letter from near Lake (or Lago) Pátzcuaro in the Mexican state of Michoacán. It was a history of what she could remember, at around age 90, of her time in Monterey, California in the 1930s and beyond, the years of John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts and so many others. She told me deep into the missive (in no uncertain terms, which was Judith’s way), “None of this group are living now, so you are lucky to get this story.” I wouldn’t argue that for a second.

Judith Deim’s Eye for Steinbeck’s Circle Never Failed

A woman of great talent and immense courage, she traveled Europe and Africa with three children—and sometimes with a band of gypsies—for 16 years. Her marriage splintered and she lost a daughter, a flamenco dancer who drowned off the coast of Spain, and her art, called Magic Realism, became dark. Yet she persevered, composing music as well as painting before dying, at the age of 95, in 2006. She was born Barbara Stevenson in 1911 in St. Louis, where her mother taught piano, and during the Depression she traveled Highway 66 with a fellow artist, Ellwood Graham. The pair met up with Steinbeck and Ricketts in Southern California, which led them to settle in Monterey, and Barbara Stevenson became Barbara Graham. The name Judith Deim came later.

A woman of great talent and immense courage, she traveled Europe and Africa with three children—and sometimes with a band of gypsies—for 16 years. Her marriage splintered and she lost a daughter, a flamenco dancer who drowned off the coast of Spain, and her art, called Magic Realism, became dark. Yet she persevered, composing music as well as painting before dying, at the age of 95, in 2006. She was born Barbara Stevenson in 1911 in St. Louis, where her mother taught piano, and during the Depression she traveled Highway 66 with a fellow artist, Ellwood Graham. The pair met up with Steinbeck and Ricketts in Southern California, which led them to settle in Monterey, and Barbara Stevenson became Barbara Graham. The name Judith Deim came later.

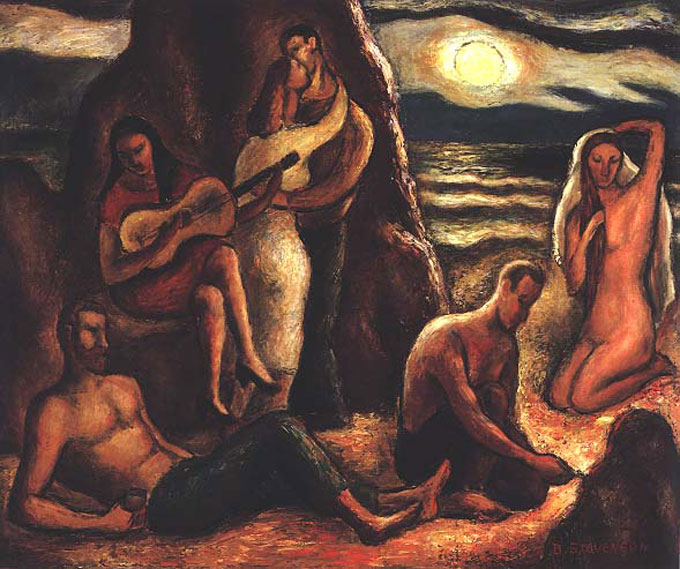

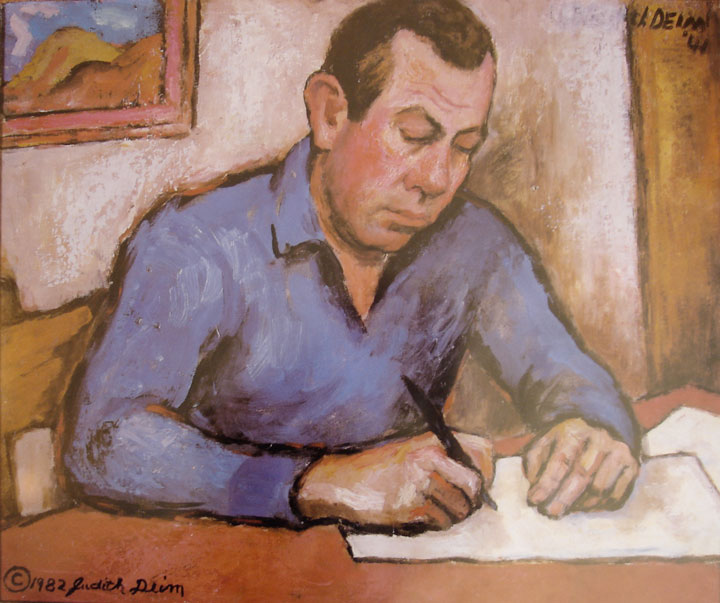

In the late 1930s she created the painting, called “Beach Picnic,” shown above. It depicts a group of companions—including a pensive-looking John Steinbeck, a broad-shouldered Ed Ricketts, and Deim herself—under a night sky. She told me once that artists, photographers, and poets used to accompany Steinbeck when (as reflected in this painting) his friends felt he needed protection. Sometimes Charlie Chaplin would drive up from Los Angeles and join them. The portrait of Steinbeck by Judith shown below hangs in the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University. The one she mentions by Ellwood Graham—a nervous yet compelling effort—has been missing for years.

Judith did not pass unnoticed. I and others wrote about her and her work was exhibited, including a solo show at the Carmel Art Association. The film about her by the award-winning director Irena Salina, “Ghost Bird: The Life and Art of Judith Deim,” was voted an audience favorite on the Sundance Channel. She had a mystical side, as shown in the transcript of the undated letter she wrote me, reproduced here for the first time. Her spelling and grammar required some touching up and she begins with a mistake—mentioning a mural in Santa Barbara which she may be confusing with one she and Ellwood worked on at the Ventura, California post office under the direction of Gordon Grant. But her perceptions of Steinbeck, Ricketts, and their circle are precise, and her eye, unlike her memory, never failed her.

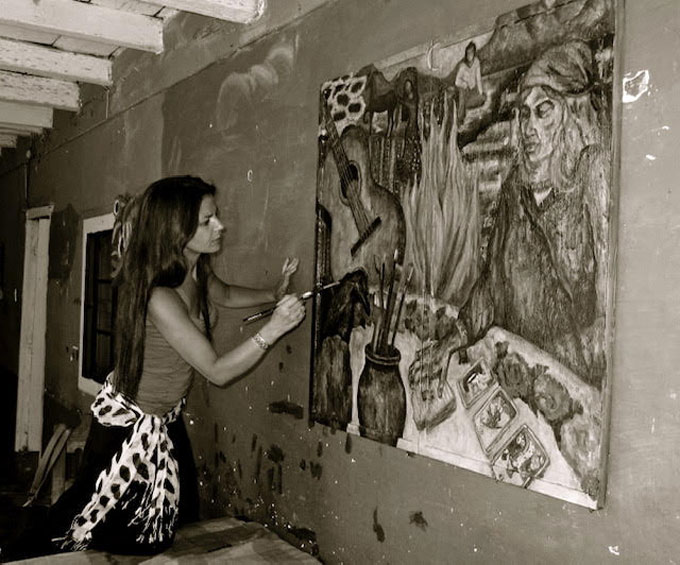

Judith Deim inspired the story “Judith” in my book Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, as well an almost completed screenplay I’m calling “The Willow Grave.” Then again, she has always been inspirational. Her sons Daniel, a sculptor, and Benje, a guitarist, continue her creative legacy. Granddaughter La Tania is a world-renowned flamenco dancer, and another granddaughter, Tiffany (shown here painting Judith), is an oil painter and muralist who works with disadvantaged kids in inner-city Los Angeles. Tiffany’s art, like that of her grandmother, expresses duende—the quality of inspired passion described by Judith in the letter.

Undated, Unpublished Letter from Judith Diem

Dear Steve—

Enclosed response to you [is] material for your article. We planned to record [the] interview with Vatche Geuvadjelian, a poet and painter, but the recording didn’t work (bad sound), so I dictated [the following for] Vatche, which he could write down far better than myself. I hope it will cover several of the questions [you] sent, improvised [with] little time to do it. Use what you wish.

I was working on a 1400-ft. mural in Santa Barbara with Ellwood Graham. I painted all the faces, sometimes mean, sometimes ugly, once in a while sweet. My work was finished [and] I left, where to? [on] the Monterey Peninsula. I met Virginia and Raymond Scardiglio; we liked each other; they invited me to live with them at their apartment in Carmel. They and 12 others of similar artistic interests were the nucleus of the group who met at Ed Ricketts[‘s] lab on Cannery Row in Monterey. There I met John Steinbeck, Ritchie Lovejoy, a writer; his wife Natalia Kashevarof, a Russian woman from Alaska; Dick and Francis Strong, Ed’s sister; Marjorie and Harold Lloyd; Henry Miller [who] came and went when his work permitted; Toby Street, John’s lawyer; and two or three others, thirteen all together. John Steinbeck and his great friend Ed Ricketts were the natural focus.

Carol Steinbeck made it possible, by working in a Relief office, for [John] to devote his time to writing. She was a wonderful country cook, with jars of preserves in all seasons. She was in rapport with all who came to the lab. She was a very important critic [of] his writing by demanding the best from him and [typing] all [of] his manuscripts.

Ed Ricketts was the ever-gracious host. He did his work, sending marine specimens all over the world. A great marine biologist, in the late hours he would disappear [in]to his lab on the ground floor and work. He loved paintings. I gave him one of an old farmwoman that he always kept above his chair, the only painting in the room.

Sometimes John spoke with me of the Big Sur. Going from the Little Sur country, his theory was [that] they were inhabited by poltergeists who were inimical to people invading the countryside and were the cause of [the] occasional disasters that occurred there.

I spent much time exploring that countryside. Sometimes I ran across the great poet Robinson Jeffers and talked with him about things he loved. His narrative poems were based on the tragic stories of people who lived in those canyons. One time I stayed behind my companions to explore an old cabin. Suddenly I felt all my strength being pulled out of me. I crawled with all my strength to get out of the cabin. I [lay] some time on a fallen tree before I continued on.

On the coast there was another well-known log cabin, run by Lolly and Bill Fassett. All [the] coast people and tourists, artists, [and] workers of the countryside gathered there. There was a bar and restaurant. Anderson Creek had been the old prison camp and had houses from the Second World War. Henry Miller and his good friends Elliott Sandow the sculptor, the Niemans, and Lilac Schatz, a fine painter, were working in these old prison houses.

A woman reporter from the Examiner [of] San Francisco came to interview all of them. They were hospitable, entertained her and showed her their work. [Then] the Sunday paper came out, devoting a whole page to the perverse [goings on and the] use of alcohol and drugs, so misusing their hospitality and their values as artists. The American Legion club members got together and planned to burn them out. [We] artists got up a petition and went to all the liberals of the community and succeeded in stopping this terrible plan.

Ellwood Graham returned to Monterey. We built [a] redwood house out of lumber we bought at an auction at Big Sur. Ellwood painted a lot of landscapes and had an experience [with] poltergeists on the Big Sur, where his canvases kept being torn from his easel even though there was no wind. He came back in a black rage, battling with the invisible. I told this story to a friend who had special photographic equipment [and] he went and took photos. The photos showed little floating light forms around the farmhouse. This related to what Steinbeck was saying about the canyons in Little Sur.

A trip was planned with two Italian brothers with their schooner to the Sea of Cortez. After much talk and discussion with the brothers they left. The idea behind the trip was for John to be inspired to write a book about the Sea of Cortez. On the trip Ed kept a log [of] everything that happened from day to day.

On their return [there was] much rejoicing, partying [and] storytelling at the lab. After a few days of this drinking and partying John felt it was time to get to work. He said, I have an inspiration. Why don’t you kids paint my portrait and I shall be forced to concentrate and get on with my book? He wanted Ellwood to have money to establish a studio. So we commissioned him to do his portrait, which he would buy whether he liked the result or not. He also wanted me to paint a portrait in any way I wanted. We celebrated his 40[th] birthday. At the time he was very proud of some Western boots he had bought for himself. He was a lot like a big child . . . . None of this group are living now, so you are lucky to get this story.

He did not like Ellwood’s portrait. [It] brought out an expressionist version of an alcoholic, which John was not. He liked my portrait very much but asked me to keep it as a souvenir, then added, “You might need it.” And I did. It was the only portrait of Steinbeck writing at his desk. I showed in on Cannery Row, where I met Steinbeck’s son [Thom]. He bought six accurately reproduced prints of the painting. I said, “I guess you like it.” He answered, “I like it because it expresses Steinbeck’s sinister side. I am having a difficult time surviving while his will waits until I [am] sixty years old to get it.” Right after the portraits [Steinbeck] suggested that he would pay for us to go to Mexico, and he said, “Go to Pátzcuaro and not to where all the tourists go.”

Pátzcuaro: in a Mexican boardinghouse with a beautiful doña. Raining and dark. At 7:00 p.m. a procession of men with torches. Very little, dim electricity, too low to read with. A dark and wild feeling, in the store windows jars of powder, of everything that humans desire: love, sex, babies, money. Only one outsider in town: a mad Englishman going in circles around the plaza without stopping. It was sad that the townspeople threw rocks to keep strangers out. But they did not throw rocks at us because I was very pregnant.

Lots of rain, and more rain. I got bronchitis and went to bed. Then the money that Steinbeck’s lawyer Toby was to send us did not arrive. The boardinghouse owner kept us going, then Ellwood went to the post office under the rain [and] returned cursing like I had never heard him before. The post office man had found the wire, but instead of paying him he had torn it right in front of Ellwood to little shreds. Finally we got paid, all in small coins. After a few days I got better and we took a boat to Janitzio, a small island in Lake Pátzcuaro. We got into the small motorboat with a married couple who still wore their wedding clothes.

By the time we got [to] the middle of the lake, storm clouds came and covered the sky. Then the motor stopped, the rain came thundering down, [and] the boat would not start, so there we sat, me coughing and soaked. In one hour a boat came and towed us to the island. A fish café [that] offered shelter played old songs [and] had an old Victrola. We were freezing so we danced, danced, and danced. I danced with [the doña] and Ellwood. I asked for a baño [and] her daughter took me to [a] totally flooded room. I made do [and] we stayed the night and [the] next day [took] a larger boat to Pátzcuaro. I had back pains [which] became serious, so we went to a doctor. He was in [the] midst of an operation but said that I had a serious infection that needed to be surgically cleaned. He finished amputating a leg in this rather dirty room [while] the nurse stripped me down and scrubbed me all over with this rather stiff brush. [The] next day [when] I was taken to be operated [on] the next operating table was full of guts and blood, [so] I bade this world goodbye. He put an old gas mask on my face and put me to sleep, 7 months pregnant. [The] next day he moved me out to the back of the station wagon because he had no room in the hospital of only one room.

Next stop Laredo, to pick up [a] money order. I stayed in the back of the car [while] Ellwood went to the post office. For an endless period of time he did not come back. Finally I struggled to get up and managed to go to the post office. He had been sent to the 5[th] floor and [the] postmaster was having him fingerprinted. On seeing me barely able to walk and very pregnant, he softened up and finally gave us the money.

We finally headed out to Monterey, Ca[lifornia]. But Ellwood started to run a high fever in the middle of Texas. We got ourselves in[to] a boardinghouse and contacted a doctor. First an old doctor [who] diagnosed malaria wanted to give him quinine, but the young assistant [who] wanted tests made in El Paso registered Ellwood into a hospital, very sick. [The] tests came back negative for malaria, but the old doctor insisted [on giving the] cure [for] this symptom. [When] the young doctor refused the older doctor appealed to my female intuition and I said, “Give him quinine.” In a few days he got better, but with big black-circled eyes.

Next [there was] a flood [and] a truck had to pull us out. Finally, [when] we got back with Steinbeck, who was anxious to see us back, [and] he took care of everything, including my delivery. There were celebrations in the lab with John and our friends. Pátzcuaro was inspiring and drew me back [in the] early [19]80s. I have painted a large number of paintings [that] I believe have “duende.”

Judith Deim

[P.S.] With so little time to write this [and] to get it off by Monday, I improvised spontaneously, trying to satisfy several inquiries [by this] subjective approach. If there is anything you would like me to elaborate on send a fax concerning it and I will fax back if possible. J.D.

“Beach Picnic” by Judith Deim courtesy of private collector. Portrait of John Steinbeck by Judith Deim courtesy Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies.