Anticipating the 80th anniversary of John Steinbeck and Edward Ricketts’s expedition to the Sea of Cortez, and the 75th anniversary of the publication of Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row, new profiles by or about a pair of writers born in England brilliantly reflect the role played by Steinbeck, Ricketts, and their free-range relationship in marrying literary imagination with marine biology to create modern ecological consciousness.

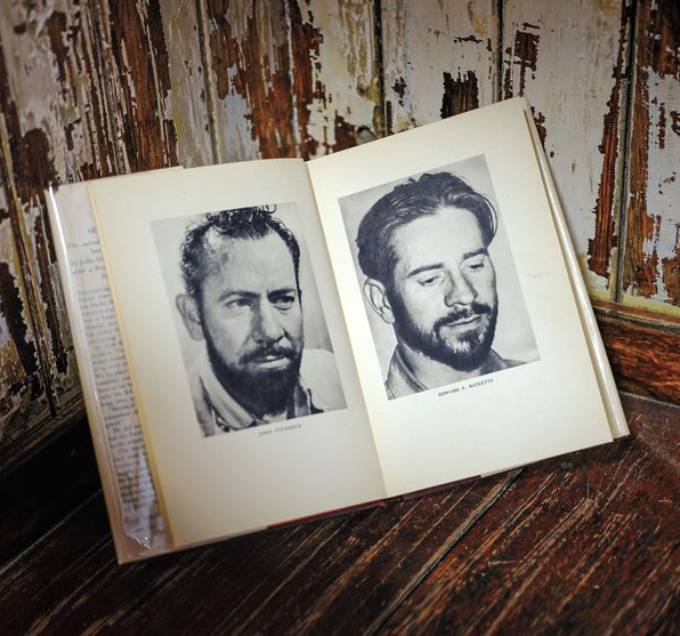

“John Steinbeck’s Epic Ocean Voyage Rewrote the Rules of Ecology”—a thoroughly researched and well-written feature by Richard Grant in the September 2019 issue of Smithsonian Magazine—recounts the 1940 journey that resulted in Sea of Cortez, the 1941 book co-authored by Steinbeck and Ricketts, and the ambitious project to restore The Western Flyer, the boat they used for their “voyage of discovery” to the waters and shores of Baja California. The fact-filled text by Grant, a British journalist based in Mississippi, is creatively complemented by photographs (like the one above) by Ian C. Bates, who lives near Port Townsend, Washington, where work on The Western Flyer continues, with an eye toward relaunch off Cannery Row in 2020.

How Cannery Row Became California

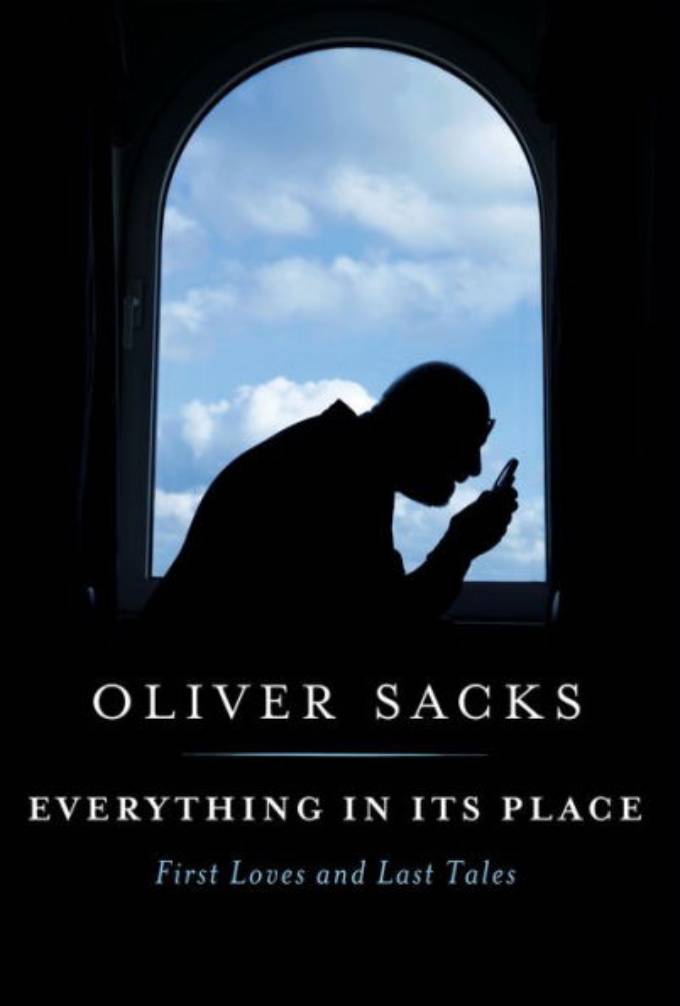

The British literary naturalist and neurologist Oliver Sacks died from cancer in August of 2015, but the prolific polymath’s debt to Sea of Cortez, Cannery Row, and the Steinbeck-Ricketts collaboration is detailed in a pair of books published in the first half of 2019. Everything in Its Place: First Loves and Last Tales, the “final volume” of essays on life, death, and Planet Earth by Sacks (who published 15 books, including Musicophilia and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) contains this paragraph about coming to Steinbeck country from Canada in 1960:

I was twenty-seven. I had arrived in North America a few months before and started out by hitchhiking across Canada, then down to California, which I had been in love with since I was a fifteen-year-old schoolboy in postwar London. California stood for John Muir, Muir Woods, Death Valley, Yosemite, the soaring landscapes of Ansel Adams, the lyrical paintings of Albert Bierstadt. It meant marine biology, Monterey, and “Doc,” the romantic marine biologist figure in Steinbeck’s Cannery Row.

How Melville and Steinbeck Became Bookends

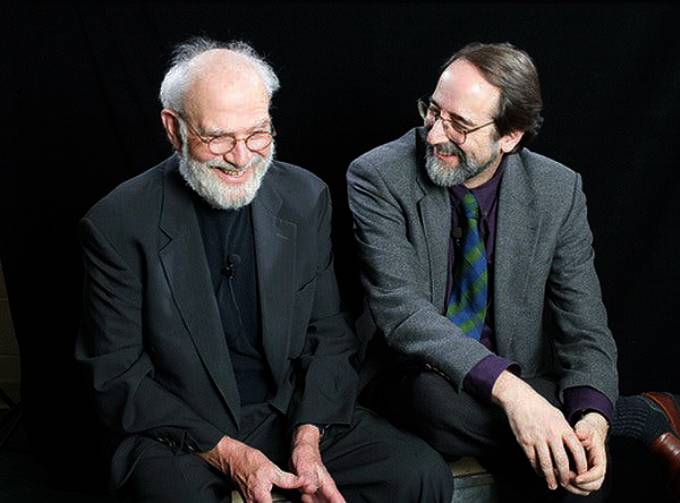

By 1982 Sacks had achieved fame as a medical renegade with literary genius for his book Awakenings, a suspenseful history of the set of post-encephalitic parkinsonian patients temporarily unfrozen by experimental L-dopa at the Bronx psychiatric hospital where Sacks worked, not without controversy, after he moved to New York. In 1982 Sacks was accompanied by the American journalist Lawrence Wechsler (at right in photo with Sacks) on a trip home to England for a New Yorker magazine profile of Sacks that never appeared. And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?—Wechsler’s memoir of the 35-year friendship that developed between the two men—records the following exchange, about influences, after a visit with Sacks’s 90-year-old father, a genial general practitioner in London who introduced his four precocious sons early (three became doctors) to the pleasures of science and reading:

Later, conversation with Oliver reverts to his childhood and school years. I ask him what sorts of books captivated him as a youth.

“Moby-Dick,” he replies, without a moment’s hesitation. “What can you say about Moby-Dick? There’s Shakespeare and there’s Moby-Dick and that’s that.

“We liked Cannery Row and Sea of Cortez, for the marine biology.” (Funny that, as bookends go: Moby-Dick and Cannery Row.)

Shakespeare, Melville, and marine biology also fired John Steinbeck’s mind. As bookends go, Oliver Sacks and Smithsonian Magazine make splendid specimens of the exultation expected in 2020 around Sea of Cortez, Cannery Row, and the marriage of marine biology and literary imagination—on both sides of the Atlantic.