Anticipating the 80th anniversary of John Steinbeck and Edward Ricketts’s expedition to the Sea of Cortez, and the 75th anniversary of the publication of Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row, new profiles by or about a pair of writers born in England brilliantly reflect the role played by Steinbeck, Ricketts, and their free-range relationship in marrying literary imagination with marine biology to create modern ecological consciousness.

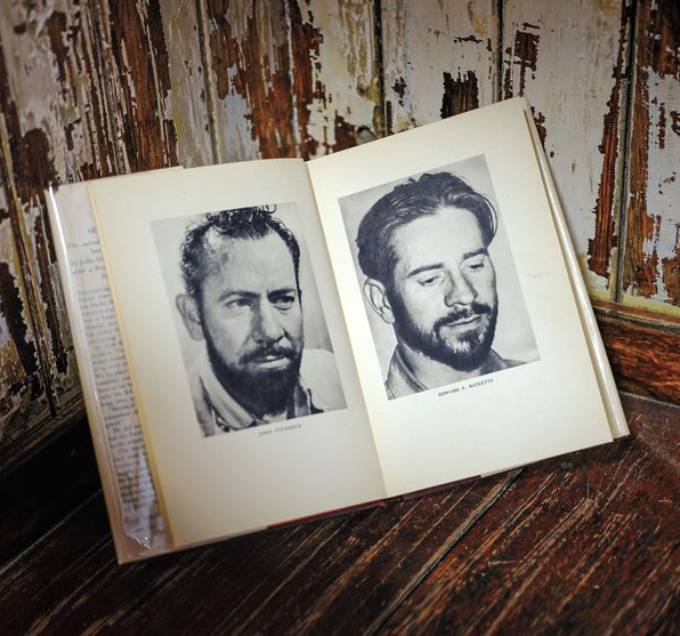

“John Steinbeck’s Epic Ocean Voyage Rewrote the Rules of Ecology”—a thoroughly researched and well-written feature by Richard Grant in the September 2019 issue of Smithsonian Magazine—recounts the 1940 journey that resulted in Sea of Cortez, the 1941 book co-authored by Steinbeck and Ricketts, and the ambitious project to restore The Western Flyer, the boat they used for their “voyage of discovery” to the waters and shores of Baja California. The fact-filled text by Grant, a British journalist based in Mississippi, is creatively complemented by photographs (like the one above) by Ian C. Bates, who lives near Port Townsend, Washington, where work on The Western Flyer continues, with an eye toward relaunch off Cannery Row in 2020.

How Cannery Row Became California

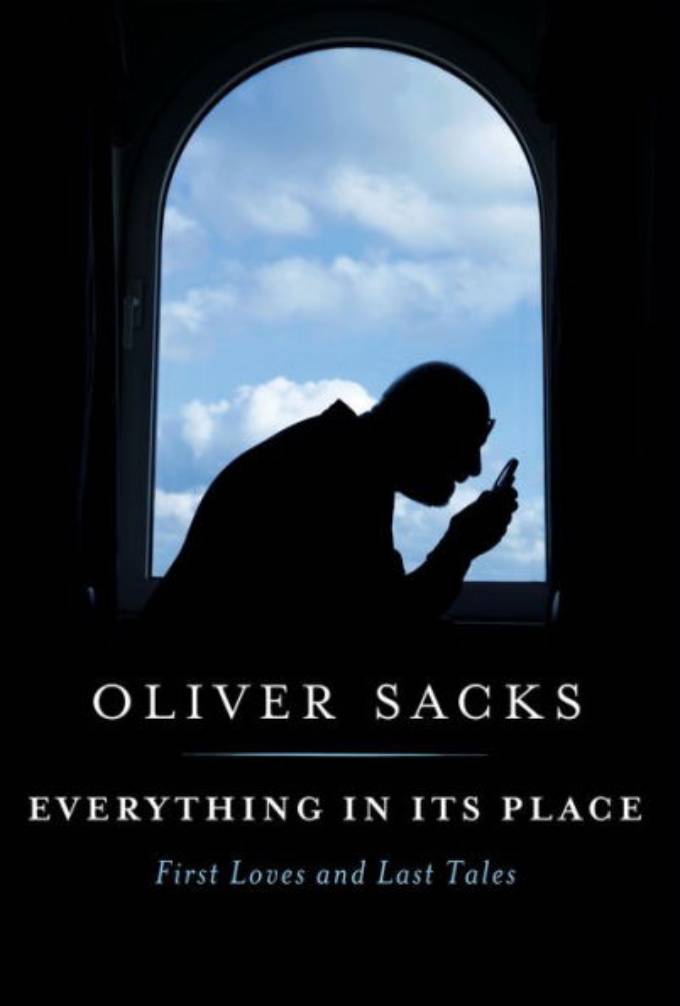

The British literary naturalist and neurologist Oliver Sacks died from cancer in August of 2015, but the prolific polymath’s debt to Sea of Cortez, Cannery Row, and the Steinbeck-Ricketts collaboration is detailed in a pair of books published in the first half of 2019. Everything in Its Place: First Loves and Last Tales, the “final volume” of essays on life, death, and Planet Earth by Sacks (who published 15 books, including Musicophilia and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) contains this paragraph about coming to Steinbeck country from Canada in 1960:

I was twenty-seven. I had arrived in North America a few months before and started out by hitchhiking across Canada, then down to California, which I had been in love with since I was a fifteen-year-old schoolboy in postwar London. California stood for John Muir, Muir Woods, Death Valley, Yosemite, the soaring landscapes of Ansel Adams, the lyrical paintings of Albert Bierstadt. It meant marine biology, Monterey, and “Doc,” the romantic marine biologist figure in Steinbeck’s Cannery Row.

How Melville and Steinbeck Became Bookends

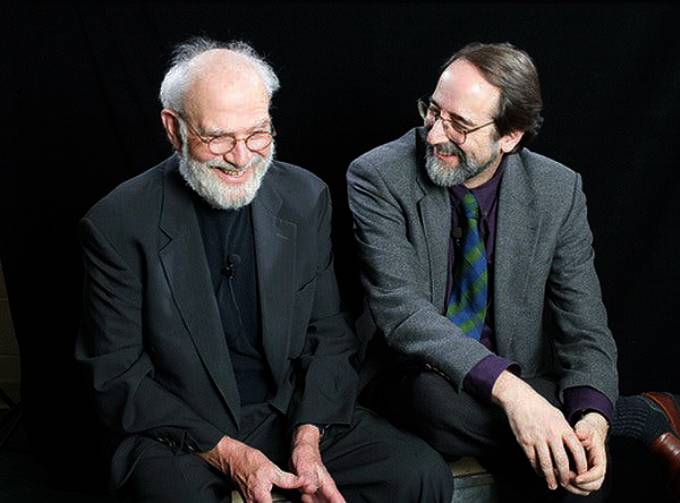

By 1982 Sacks had achieved fame as a medical renegade with literary genius for his book Awakenings, a suspenseful history of the set of post-encephalitic parkinsonian patients temporarily unfrozen by experimental L-dopa at the Bronx psychiatric hospital where Sacks worked, not without controversy, after he moved to New York. In 1982 Sacks was accompanied by the American journalist Lawrence Wechsler (at right in photo with Sacks) on a trip home to England for a New Yorker magazine profile of Sacks that never appeared. And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?—Wechsler’s memoir of the 35-year friendship that developed between the two men—records the following exchange, about influences, after a visit with Sacks’s 90-year-old father, a genial general practitioner in London who introduced his four precocious sons early (three became doctors) to the pleasures of science and reading:

Later, conversation with Oliver reverts to his childhood and school years. I ask him what sorts of books captivated him as a youth.

“Moby-Dick,” he replies, without a moment’s hesitation. “What can you say about Moby-Dick? There’s Shakespeare and there’s Moby-Dick and that’s that.

“We liked Cannery Row and Sea of Cortez, for the marine biology.” (Funny that, as bookends go: Moby-Dick and Cannery Row.)

Shakespeare, Melville, and marine biology also fired John Steinbeck’s mind. As bookends go, Oliver Sacks and Smithsonian Magazine make splendid specimens of the exultation expected in 2020 around Sea of Cortez, Cannery Row, and the marriage of marine biology and literary imagination—on both sides of the Atlantic.

Once I attained adult consciousness and maturity, my life journey has been one of world and self exploration and discovery. To me this and the resulting lessons are the purposes of this life experience.

As Swiss psychiatrist Carl G. Jung pointed out, given the scope of the universe or our Earth, it is humanly impossible to consider the whole thing and we must, therefore be satisfied with exploring bite sized pieces to form conclusions on the whole. It is the same with the individual human psyche.

Within that philosophical context, when I am asked what Steinbeck books I feel most influenced my life the two I name are Cannery Row and The Sea Of Cortez (kco authorred with Edward F. Ricketts), more specifically The Log From The Sea Of Cortez. The former because it was a somewhat idealized story of a loving community of widely diverse characters reflected what I believed was the goal of the American founding fathers for a society living for generations in freedom and liberty.

The Sea of Cortez convinced me of a direct Jungian influence on Steinbeck writing that had only been my theory up to that time. There’s no doub about it, Steinbeck writing includes the practical application of psychology as described by Jung and Harvard professor William James. It is a philosophical gold mine for explorers.

The concept of “bite size pieces” is the the building blocks of Steinbeck’s informal networks which is the core of his social ecology theory that he created and used in his writings. How could he not have created such a theory hanging out with Ed Ricketts and absorbing his Marine Biological consciousness. The “bite size pieces” shows up in a recently discovered story he wrote for the French Daily Le Figaro. He rented a place in Paris in 1954 near the Champs-Elysees in Paris. He wrote many columns, but this one was recently discovered at the Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. It has now been translated into English and published by the Strand literary magazine, July, 2019 for the first time.

It is a delightful and humorous story called: “The Amiable Fleas”. As you know I have spent many years constructing and applying a major Social Ecology theory from Steinbeck’s writings never quite finding a direct statement about his approach to writing about the people. Well in his introductory paragraph in The Amiable Fleas he made the following statement: “I am sometimes criticized for avoiding the great discordant notes for the times and closing my ears to the drums of daily doom. But I have found that the momentary sound very well shortly becomes a whisper and the timely fury is forgotten, while the ‘soft verities persist year after year’. (my quotes added). ……..Suppose I were to write of these important matters! By the time my piece were printed all would be past and much of it forgotten and there would be new earthquakes……We have not survived on great things, but on little ones.” Informal networks persist year after year for generations they carry the culture, the survival, the taking care of each other essentially the social ecosystem. Informal networks are the ‘soft verities’ that persist year after year.

This is a clearest statement he has ever made about the difference between the ecological concept of social ecological persistence (soft varities) as distinguished from vertical systems that are based on transactional concepts (discordant notes) not ecological processes.

So your “bite size pieces” reference got me to write this dissertation to you about how Steinbeck understood exactly that in his writings. The bite size pieces eventually aggregate to powerful action but they come from the “ground up” not the “top down” as Steinbeck has so eloquently expressed in his writings.

Jim Kent

Beautiful Jim, as usual. Thank you. There is so much work to do to change old tired perceptions of life, love, and liberty and it must be done.

Wes Stillwagon

Thanks for keeping this good stuff in circulation, Will! The SOC piece from Smithsonian is especially valuable, and the Oliver S connection to JS is new to me. Thanks for keeping all of us informed.

An interesting pairing, the journalist and the scientist, and the Smithsonian article is well worth reading.

I was in Washington last year and spent some time and effort in an unsuccessful attempt to see the Western Flyer in her partially rebuilt condition in Port Townshend . The place was locked up tight, no one around, the windows covered so that even a glimpse of the craft was impossible. I’ll have to wait until she’s returned here to Monterey County. In the meantime, a re-read of “The Log…” will suffice.

Dale Bartoletti