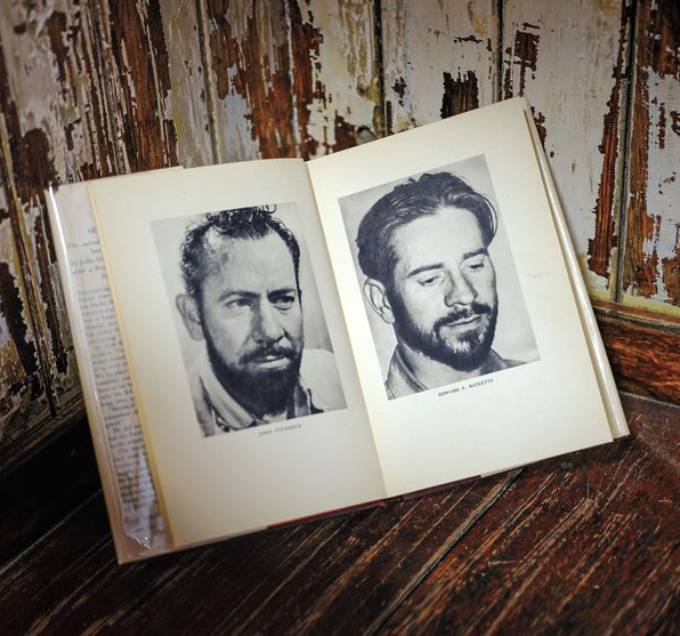

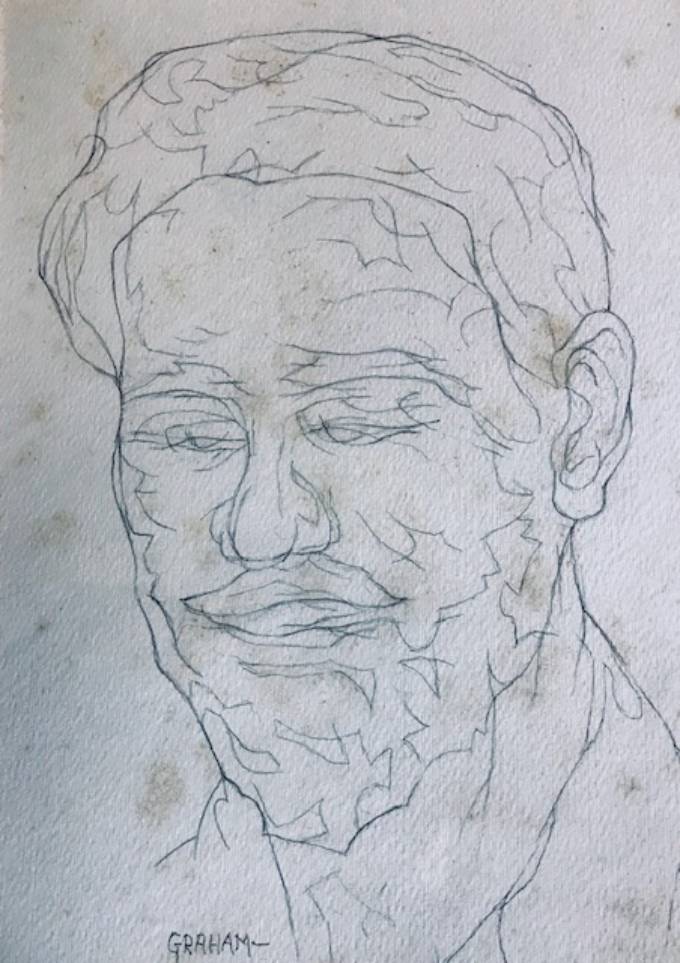

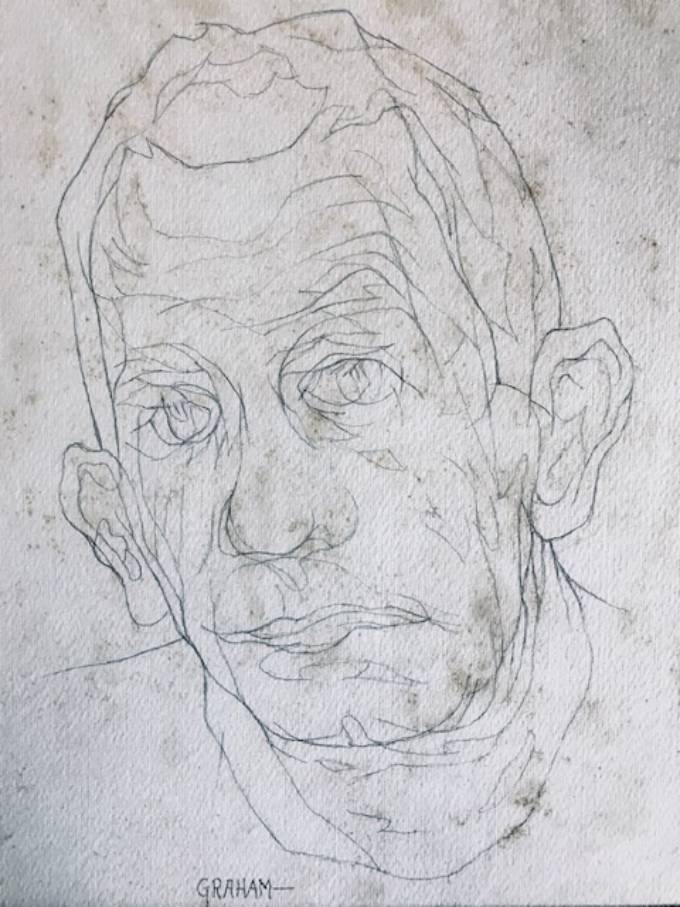

Numerous artists drew, painted, or photographed John Steinbeck, but artistic images of his friend Ed Ricketts are relatively rare. This made the chance discovery of a drawing of Ricketts by Ellwood Graham—in a Carmel, California art collection that also includes Graham’s sketch of Steinbeck—especially exciting. Both drawings are discolored and have acid burn, but Graham’s lines are vivid and the impression in both, even before restoration, remains strong.

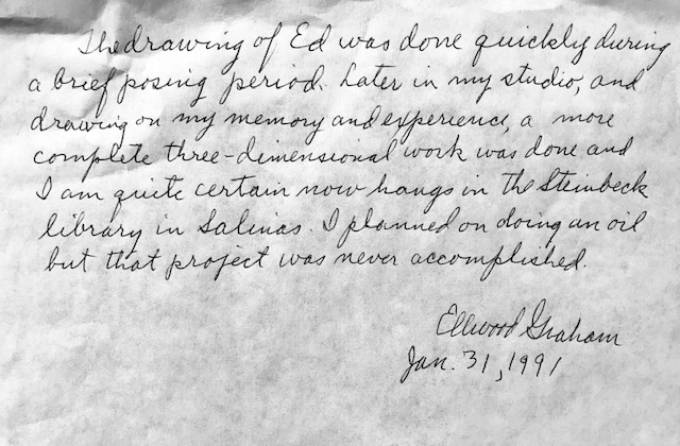

In 1991 Graham penned his remembrance of doing the two drawings (shown here) around 1940-41, and in 1995 they were included in a Monterey Museum of Art exhibition, curated by Richard Gadd and called “Monterey Life: The Steinbeck Years.” Ironically, when I came across the pair on my first visit to a Carmel collector’s home several months ago I was writing The Willow Grave, a screenplay on Graham and his wife Judith Deim. Ricketts and Steinbeck are significant characters in the story.

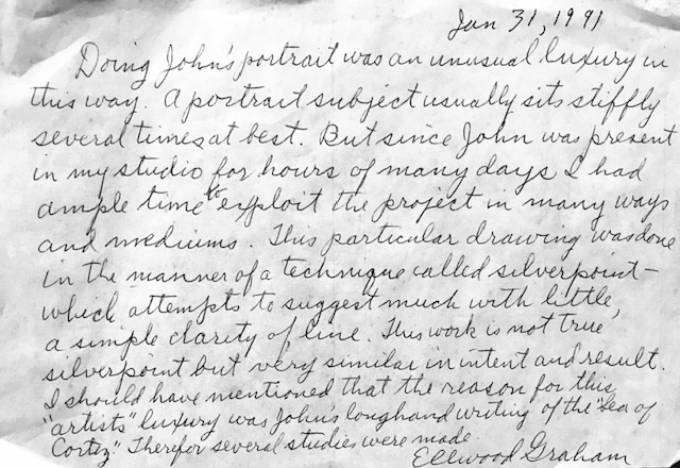

“Doing John’s Portrait Was an Unusual Luxury” for Artist

Graham’s recollection of sketching Steinbeck was still fresh when he wrote this note:

Doing John’s portrait was an unusual luxury in this way. A portrait subject usually sits stiffly several times at best. But since John was present in my studio for hours of many days, I had ample time to exploit the project in many ways and mediums. This particular drawing was done in the manner of a technique called silverpoint – which attempts to suggest much with little, a simple clarity of line. This work is not true silverpoint but very similar in intent and result. I should have mentioned that the reason for this “artists” luxury was John’s longhand writing of “The Sea of Cortez.” Therefor several studies were made.

Equally strong was Graham’s memory of sketching Ricketts:

The drawing of Ed was done quickly during a brief posing period. Later in my studio, and drawing on my memory and experience, a more complete three-dimensional work was done and I am quite certain hangs in the Steinbeck library in Salinas. I planned on doing an oil but that project was never accomplished.

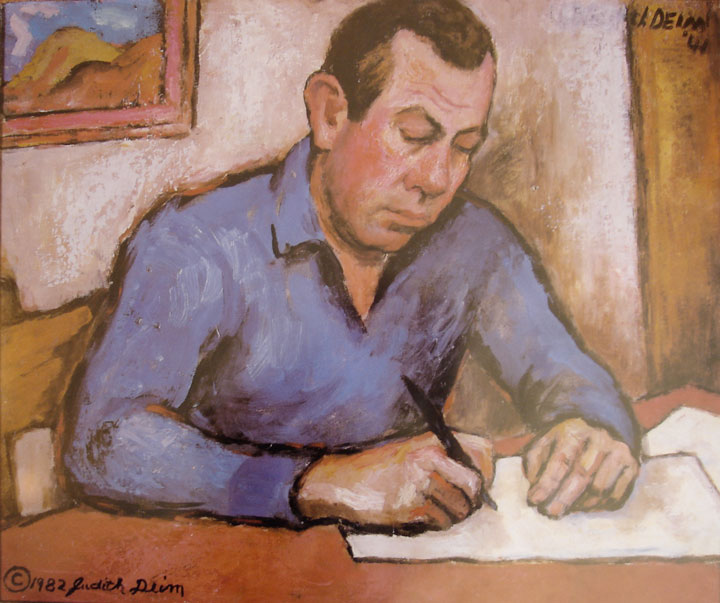

Ellwood Graham and Judith Deim—then going by her given name of Barbara Stevenson—were artists from St. Louis, Missouri, who made their way to California on Route 66 during the Dust Bowl days of the Great Depression. By chance in Los Angeles they met Gordon Grant, the California artist who was creating murals under the auspices of the Federal Art Project, and he hired them. They were working on the mural in the Ventura, California post office when—again a chance meeting—they met Steinbeck and Ricketts, who were passing through on their way to Mexico. Before parting, Ricketts and Steinbeck invited the young artists to visit Monterey, which, of course, they eventually did. Deim was to do her own portrait of Steinbeck (shown here). It is in the collection of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies. Graham also did an oil portrait of the writer, but it was lost and its whereabouts are unknown.

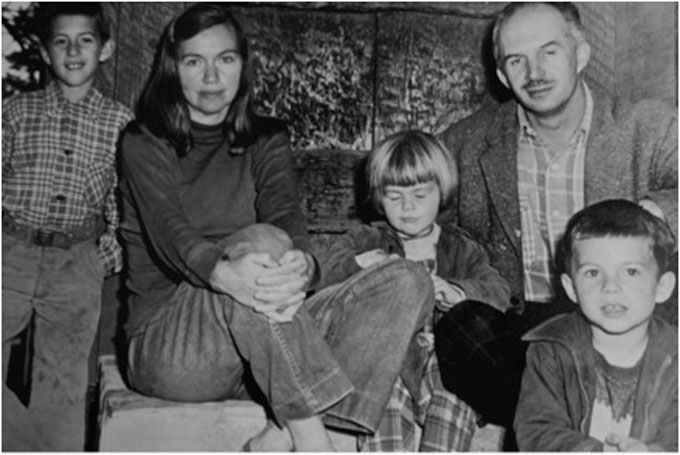

Newlyweds, Deim and Graham (shown with their children in this undated photo) met as students in the School of Fine Arts at Washington University and went on to distinguished careers in California and Mexicao. Deim exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Palace of the Legion of Honor, and the Patzcuaro Museum (she spent the last years of her life in Mexico’s Michoacan). Among many honors, she was the first artist given a solo exhibition at the Carmel Art Association, in 1946. Graham has work in the Whitney Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the De Young Museum, and the Monterey Museum of Art. Among dozens of exhibits and solos, he had work in the 1939 Golden Gate International Exhibition in San Francisco. Deim spent her last years in Mexico. Graham died in Oregon.

An art dealer in Los Angeles who specializes in early modernism told me he knew Graham had a strong sense of his worth as an artist, “because when I find his old paintings, they usually have a pretty high price—for the time—on the reverse side.” Steinbeck and Ricketts believed in Graham and Deim’s talent; Steinbeck, for instance, felt easy enough in their presence to write while they painted him. Luck brought Graham and Deim to the attention of Gordon Grant in Los Angeles and Ricketts and Steinbeck at the Ventura post office. I, too, was fortunate to happen upon Ellwood Graham’s drawings in that Carmel collection.

Ellwood Graham’s recently rediscovered sketches of John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts courtesy of private collector in Carmel, California.

Great find Steve! Especially powerful when presented side by side.

David, in Larry McMurtry’s novel Cadillac Jack, the hero, down on his luck and his car broken down on the edge of a Nevada desert, kicks the sand in frustration – and a collector’s soda bottle worth a bit of money pops up. Jack then formulates the theory, as I recall, of “Anything can be found anywere.”Art has always seemed to have a way of resurfacing.