“Bruton is the only spot in the world I have refused to see again since John died.”

– Elaine Steinbeck

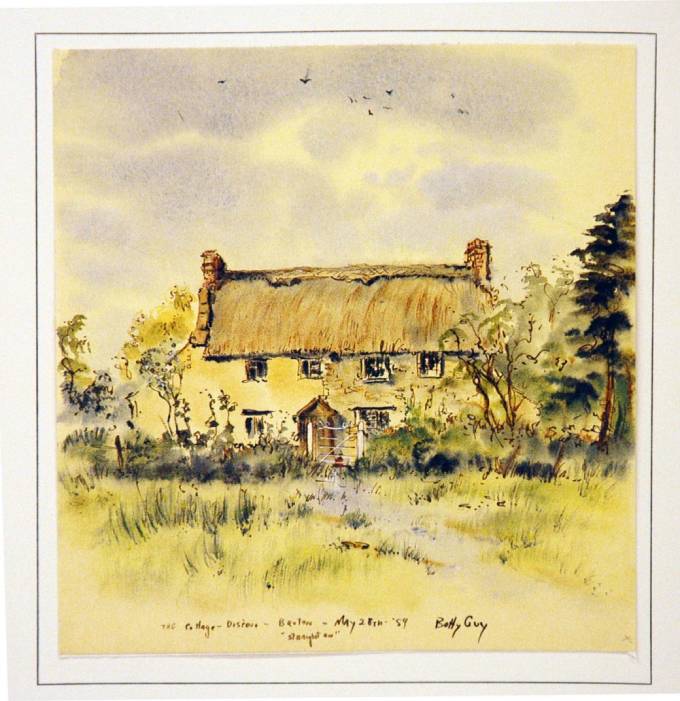

Elaine Steinbeck’s comment in a 1992 letter to the artist Betty Guy refers to the time that she and her husband John Steinbeck spent at Discove Cottage in Bruton, Somerset, England, while he worked on his “reduction of Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur to simple readable prose without adding or taking away anything.” The story behind the story of Steinbeck’s Arthurian quest started 80 years earlier, in California.

The Road from Castle Rock

Steinbeck became fascinated with the legends of King Arthur and the Round Table after his Aunt Molly Martin presented him with a child’s version of the epic tales of chivalry and knighthood on his ninth birthday. He created a secret language based on Malory’s text and, with his sister Mary, played among the exotic eroded turrets of Castle Rock in Corral de Tierra, near Salinas, as their imaginary Camelot. Arthurian themes appeared in Cup of Gold, Tortilla Flat, Of Mice and Men, and many other writings. He began working on Arthur in earnest after completing The Short Reign of King Pippin IV in 1957, work that went through numerous false starts and iterations and consumed Steinbeck for the rest of his life. As late as 1965, in a letter to the actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Steinbeck wrote: “Perhaps you will remember that for at least thirty-five years, and maybe longer, I have been submerged in research for a shot at the timeless Morte d’Arthur. Now Intimations of Mortality warn me that if I am ever going to do it, I had better start right away, like next week.”

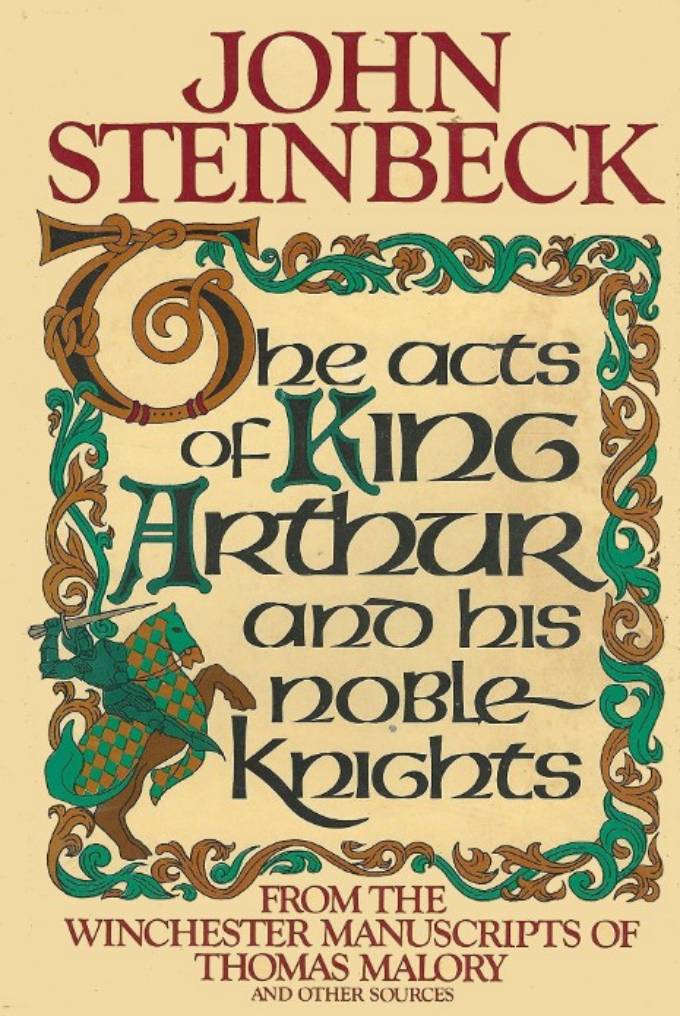

Ultimately Steinbeck failed in his quest to transpose the music of Malory’s language for modern ears. Two unfinished draft manuscripts survive, one created in Somerset, the second written some years after his return. Initially concerned that it would detract from his reputation, Elaine relented to posthumous publication when she realized that her husband had incorporated references to his love for her. Edited by Chase Horton (owner of the Washington Square Bookstore in New York and a friend of his agent Elizabeth Otis), The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knight appeared in 1976. The volume includes an extensive appendix drawn from the author’s letters and journals.

In his correspondence, Steinbeck describes the heights of elation and the depths of despair he experienced while pursuing his search for artistic perfection.

In this correspondence, the writer describes the heights of elation and the depths of despair he experienced while pursuing his search for artistic perfection. One unwavering theme is the sense of joy and contentment in the simple lifestyle he enjoyed during the months spent researching and writing in Discove Cottage, near Bruton in Somerset, England, in 1959. The biographies of Steinbeck by Jackson J. Benson (The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer) and Jay Parini (John Steinbeck: A Biography) recount Elaine’s recollection of a conversation with her husband during his final hours of life. He asked her, “What’s the best time we ever had together?” “The time at Discove,” they agreed. Parini quotes Elaine: “John had discovered something about himself in Discove Cottage.”’ Elaine never returned to Discove, but she remained friendly with the owner, Mrs. Kay Leslie, and she visited the Leslies several times after they sold the cottage to Mr. and Mrs. David Whigham in 1977. Perhaps recalling her husband’s disappointing return to Monterey as recounted in Travels with Charley, Elaine did not wish to disturb the memories of their idyllic sojourn in that humble rural cottage.

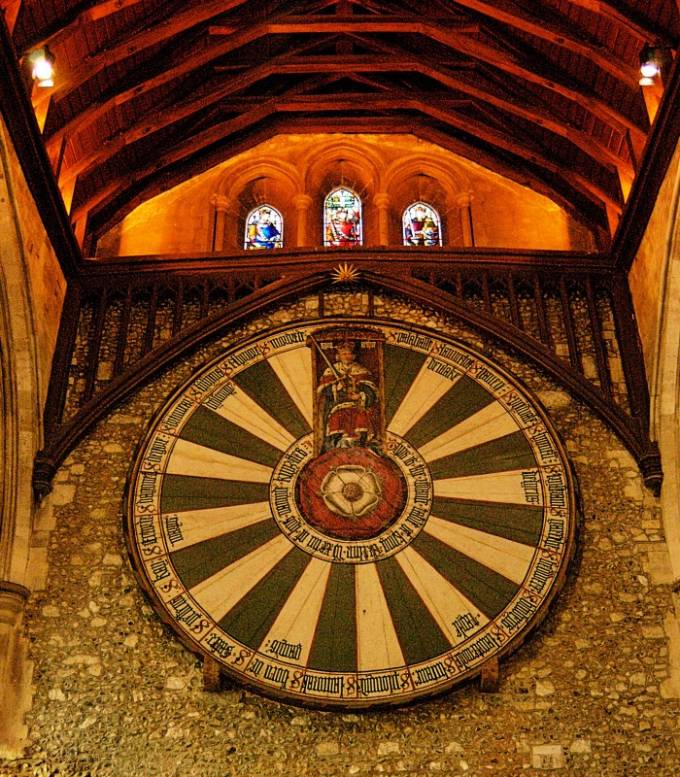

Exploring England’s Camelot Country

During 1957 and 1958, the Steinbecks traveled Europe in search of original material. John researched in the Vatican libraries in Rome as he believed Sir Thomas Malory had traveled to Italy as a mercenary. In England they met with Professor Eugene Vinaver, a scholar and authority on the 15th century, and toured many Arthurian locations across the country, including Glastonbury Tor in Somerset, the heart of King Arthur Country, and the medieval replica of the Round Table at Winchester Castle. Stage and screenwriter Robert Bolt (A Man for All Seasons, Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago), who taught English at the nearby Millfield school, introduced them to other ancient English traditions, including cricket and the village pub.

‘I am depending on Somerset to give me the something new which I need,’ wrote Steinbeck.

In July 1958, Steinbeck started work on the translation at his retreat in Sag Harbor, New York, but soon reached an impasse in his search for an appropriate “path or a symbol or an approach.” Believing that he could find this thread in England (“I am depending on Somerset to give me the something new which I need”), he and Elaine crossed the Atlantic again in February 1959. They landed at Plymouth, took delivery of a Hillman Minx estate car (station wagon), and drove to the ancient market town of Bruton. Here they rented Discove Cottage, located for them by Robert Bolt on the estate of Discove House. Steinbeck was so pleased with Bolt’s find that he presented him a gift of the complete thirteen-volume edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.

In July 1958, Steinbeck started work on the translation at his retreat in Sag Harbor, New York, but soon reached an impasse in his search for an appropriate “path or a symbol or an approach.” Believing that he could find this thread in England (“I am depending on Somerset to give me the something new which I need”), he and Elaine crossed the Atlantic again in February 1959. They landed at Plymouth, took delivery of a Hillman Minx estate car (station wagon), and drove to the ancient market town of Bruton. Here they rented Discove Cottage, located for them by Robert Bolt on the estate of Discove House. Steinbeck was so pleased with Bolt’s find that he presented him a gift of the complete thirteen-volume edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Discove House is a Grade II Listed Building. The two-storey stone house features a projecting porch and a steep thatched roof between coped gables. Although it does exhibit earlier features, much of the structure dates from the 17th century. At 140 feet in length, the house is said to be the longest thatched residence in England. Steinbeck called it an “old manor house,” but Discove was more likely the dower house for the nearby Redlynch Estate of the Earls of Ilchester. A dower house is a residence reserved for the widow when an entailed estate passes on to the older son.

Discove Cottage is a former farm laborer’s dwelling hidden from the road in the fields behind the main house.

Discove Cottage is a former farm laborer’s dwelling hidden from the road in the fields behind the main house. It has two bedrooms upstairs and a kitchen-dining room and a living room downstairs. According to Steinbeck, “It has stone walls three feet thick and a deep thatched roof and is very comfortable . . . . It is probable that it was the hut of a religious hermit. It’s something to live in a house that has sheltered 60 generations.”

The name Discove is believed to derive from a combination of the proper names Dycga or Diga and the Anglo-Saxon word for bedchamber or hut.

The name Discove is believed to derive from a combination of the proper names Dycga or Diga, used by monks 600-800 AD, and the Anglo-Saxon word cove, for bedchamber or hut. In the 1086 AD Doomsday Book of William the Conqueror, it is recorded as Dinescove. The surrounding area has been occupied since ancient times. A possible barrow, or Neolithic burial chamber, has been identified at Redlynch, and a tessellated pavement from the Roman era, 1,000 years before the Conqueror, was uncovered at Discove in 1711.

‘We are right smack in the middle of Arthurian Country.’ wrote Steinbeck. ‘And I feel that I belong here. I have a sense of relaxation I haven’t known for years. Hope I can keep it for a while.’

The Steinbecks settled into rural life quickly. “Elaine is seeding Somerset with a Texas accent,” wrote Steinbeck. “She’s got Mr. Windmill of Bruton saying you-all. At the moment, she is out in the gallant little Hillman calling on the vicar.” As for the task at hand, “If ever there was a place to write the Morte, this is it. Ten miles away is the Roman fort, which is the traditional Camelot. We are right smack in the middle of Arthurian Country. And I feel that I belong here. I have a sense of relaxation I haven’t known for years. Hope I can keep it for a while.”

“Yesterday I cut dandelions in the meadow and we cooked them for dinner last night—delicious,” Steinbeck reported. “And there’s cress in the springs on the hill. But mainly there’s peace—and a sense of enough time.” The praise approached mysticism. “I can’t describe the joy. In the mornings I get up early to have time to listen to the birds. It’s a busy time for them. Sometimes for over an hour I do nothing but look and listen and out of this comes a luxury of rest and peace and something I can only describe as in-ness. And then when the birds have finished and the countryside goes about its business, I come up to my little room to work. And the interval between sitting and writing grows shorter every day.” Elaine agreed: “John’s enthusiasm and excitement are authentic and wonderful to see. I have never known him to have such a perfect balance of excitement in work and contentment in living in the ten years I have known him.”

The grail of modern translation may have eluded Steinbeck, but the months at Discove had been wonderful: ‘this has been a good time—maybe the best we have ever had.’

The idyll was broken in May when Otis and Horton told Steinbeck that they were disappointed with the first section of the manuscript he had submitted to his agents in New York. “To indicate that I was not shocked would be untrue,” replied Steinbeck. “I was.” For the rest of the summer, Steinbeck struggled but failed to find his voice. In September he wrote, “Our time here is over and I feel tragic about it. . . . The subject is so much bigger than I am. It frightens me.” The grail of modern translation may have eluded Steinbeck, but the months at Discove had been wonderful: “this has been a good time—maybe the best we have ever had.”

Discovering Discove Decades After Steinbeck

While visiting friends in the west of England in 2005, my wife and I took a detour to Bruton to see if the cottage still looked as Steinbeck described it. On a cold, wet English October day, the Whighams welcomed us to morning coffee in the richly carved oak-paneled living room of Discove House, their home. The prior owner, Mrs. Leslie, had advised them of the estate’s literary connection. They told us that a crew from the BBC had filmed the cottage several years before for a Steinbeck documentary. They also recounted a bit of the house’s post-Norman history, including the addition of the “new” wing in 1750 to accommodate Lady Ilchester, who did not wish to return to Redlynch in the dark after her weekly bridge game.

It may be a little worse for wear, but the narrow iron gate in the boundary hedge remains. On pushing it open and strolling in the quiet of the enclosed garden, I immediately sensed the peace and contentment that fills those letters of half a century ago.

I gave David Whigham a copy of the National Steinbeck Center visitor guide that features the painting of Discove Cottage by Betty Guy. Steinbeck’s editor, Pascal Covici, had commissioned her to visit Bruton to paint the cottage as a Christmas gift for the Steinbecks in 1959. Seeing the thatched roof in the picture, the Whighams noted that it had been replaced with tiles before they acquired the building. During a pause in the rain, we walked across the lush green meadow to the cottage. The small wooden porch over the front door was gone, and the fledgling cypress tree in the 1959 painting towered over the house in 2005. It may be a little worse for wear, but the narrow iron gate in the boundary hedge remains. On pushing it open and strolling in the quiet of the enclosed garden, I immediately sensed the peace and contentment that fills those letters of half a century ago.

I was delighted to learn that this was the table upon which a literary giant crafted his evocative letters extolling the joys of ‘the time at Discove’ all those decades ago.

David mentioned that he and his wife had acquired all the furniture with the cottage. Mrs. Leslie had told him that it included a work desk and other items purchased by Steinbeck. I was most curious about a table-top draftsman’s board manufactured by Admel Drafting Equipment and supplied by Lawes Rabjohns Ltd. of Westminster. On our return to California, I found several references to the table in Steinbeck’s correspondence with Chase Horton. On April 25, 1959, he wrote, “My table-top tilt board came. Makes a draftsman’s table of a card table. My neck and shoulders don’t get so damned tired.” I contacted Betty Guy in San Francisco to ask if she had noticed a table when she was invited to the writer’s room to sketch from the window. She said she had: “When John asked me up to his room he showed me his slanted work table, so it must have been the draftsman’s table.” I was delighted to learn that this was the table upon which a literary giant crafted his evocative letters extolling the joys of “the time at Discove” all those decades ago. Steinbeck’s work table is currently on display in the Bruton Museum.

David mentioned that he and his wife had acquired all the furniture with the cottage. Mrs. Leslie had told him that it included a work desk and other items purchased by Steinbeck. I was most curious about a table-top draftsman’s board manufactured by Admel Drafting Equipment and supplied by Lawes Rabjohns Ltd. of Westminster. On our return to California, I found several references to the table in Steinbeck’s correspondence with Chase Horton. On April 25, 1959, he wrote, “My table-top tilt board came. Makes a draftsman’s table of a card table. My neck and shoulders don’t get so damned tired.” I contacted Betty Guy in San Francisco to ask if she had noticed a table when she was invited to the writer’s room to sketch from the window. She said she had: “When John asked me up to his room he showed me his slanted work table, so it must have been the draftsman’s table.” I was delighted to learn that this was the table upon which a literary giant crafted his evocative letters extolling the joys of “the time at Discove” all those decades ago. Steinbeck’s work table is currently on display in the Bruton Museum.

This article has been adapted by the author from a version originally published in the Fall 2006 issue of Steinbeck Review. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations attributed to Steinbeck are from The Acts of King Arthur and his Noble Knights, ed. Chase Horton (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976), and Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten (New York: Viking, 1975).