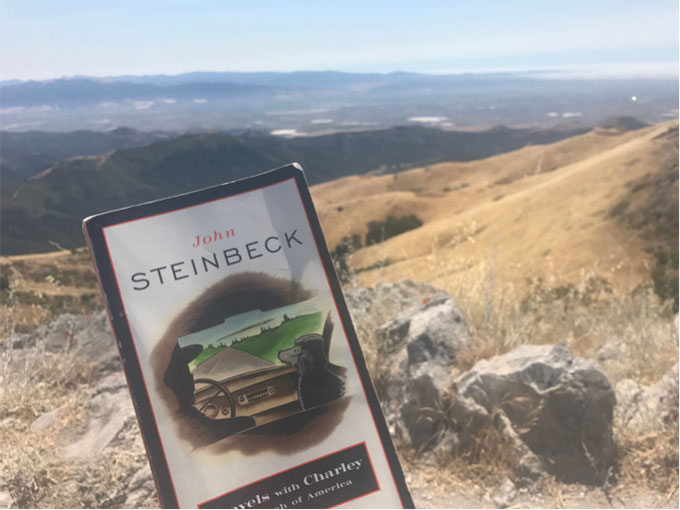

Did John Steinbeck foreshadow the genre-bending literary movements now known as New Journalism and creative nonfiction when he wrote Travels with Charley, his semi-fictional account of the road trip he and his dog Charley took “In Search of America” in the fall of 1960? Published in 1962 as a book of travel, Steinbeck’s carefully crafted narrative resonated with mid-century readers who may or may not have felt differently if they had known Steinbeck was manipulating chronology and making up characters and conversations, like a novelist, to move his audience and fit his message.

When I first read Travels with Charley I had my doubts about several episodes in the book.

When I first read Travels with Charley, half a century after it was written, I had my doubts about several episodes in the book—encounters with Sunday preachers, Shakespearean actors, straight fathers and gay sons, Southerners with neatly divided views on race—that seemed uncharacteristically wooden for Steinbeck, too conveniently timed and too clearly contrived to prove the author’s point about the moral condition of America at the tail end of the Eisenhower era. By this time I was a frequent user of Jackson Benson’s magisterial biography, The Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, but I hadn’t read Bill Steigerwald’s exposé, Dogging Steinbeck, and I didn’t become concerned with the choices Steinbeck made in Travels with Charley until I started my own research into the choices he confronted when he undertook the subject of religion in his writing.

Having failed to find the John Knox church in Vermont that Steinbeck says he attended, I turned for help to Dogging Steinbeck.

In 2014, having failed to find the John Knox church in Vermont that Steinbeck says he attended in Travels with Charley, I turned for help to Dogging Steinbeck and learned that, like other scenes, the churchgoing episode with the fire-and-brimstone preacher was a likely fabrication designed to further the persona and purpose Steinbeck set out to advance in his book. Steigerwald, a veteran Pittsburgh journalist, had retraced Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile road trip as faithfully as possible in 2010 for an online newspaper series and discovered proof that Travels with Charley was heavily fictionalized. Though the New York Times praised Steigerwald on its editorial page for blowing the literary whistle on Steinbeck’s iconic road book, he caught grief from scholars and fans alike when Dogging Steinbeck came out in 2012. But as the journalist and author William Souder notes in Mad at the World, the new life of Steinbeck scheduled for publication in October, “Steigerwald could be forgiven for applying the rules of journalism to a work that purported to be journalism. First among those rules is that facts matter.”

Recently I caught grief of my own from a conscientious reader for appropriating the term creative nonfiction in a post about the sequel, Chasing Steinbeck’s Ghost.

Recently I caught grief of my own from a conscientious reader for appropriating the term creative nonfiction in a post about Steigerwald’s new e-book sequel, Chasing Steinbeck’s Ghost. I turned to Steigerwald and Souder for their advice on the subject, and both replied.

Bill Souder and Bill Steigerwald on a Sensitive Subject

Explained Souder, a literary expert whose 2004 biography of John James Audubon was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize: “The term ‘creative nonfiction’ has been muddied up in recent years, mainly, I think, by memoirists. But being the old school stick-in-the-mud that I am, I prefer the original definition: Creative nonfiction = The truth, well told. By that light, ‘creative’ does not nullify ‘nonfiction.’ It’s not a license to invent.

Creative nonfiction has roots in the New Journalism of the 1960s and 1970s.

“Creative nonfiction has roots in the New Journalism of the 1960s and 1970s, when writers like Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, Truman Capote, Hunter Thompson, Norman Mailer, et al made their reporting more dynamic and engaging by using the narrative and descriptive techniques of fiction writing . . . including, in many cases, becoming their own first-person narrators. But they didn’t make up what happened. They only made it more interesting. One of the archetypes of the genre is Capote’s In Cold Blood, a true story that reads like a thriller.

Travels with Charley is an inventive, incisive essay on America that, because Steinbeck made some of it up, can’t really be called a snapshot.

“I don’t think your readers will mind the term as you deploy it here, but if it were my call I’d use something different. Travels with Charley is an inventive, incisive essay on America that, because Steinbeck made some of it up, can’t really be called a snapshot. It’s more like a painting.”

I agree about creative fiction being ‘truth, well told.’ It’s really how I used to think of newspaper/magazine journalism.

Adds Steigerwald, a contrarian reporter with a libertarian perspective on Steinbeck’s politics: “I agree about creative nonfiction being ‘truth, well told.’ It’s really what I used to think was the purpose of newspaper/magazine journalism—presenting/deploying important or interesting facts in an entertaining, informative, fair-and-balanced narrative way without distorting the truth. The difficulty is/was that too many newspaper proles in my era—at the Los Angeles Times and two Pittsburgh dailies from 1977 to 2009—were better at gathering facts than presenting them in an interesting way on paper. Or the writers/reporters were too politically or culturally biased, deliberately or without even knowing it, to be able to stick to the ‘truth’ and balance of their story while they performed their creative tricks.”

Email your idea for a post of your own about the truth or falsity of creative nonfiction. It’s a surprisingly sensitive subject.

I can’t improve on either summary, but you’re invited to try. If you’re a protective fan of Steinbeck’s writing with something to say about the foreshadowing of New Journalism in Travels with Charley, please leave a comment on this post. Or email your idea for a post of your own about the truth or falsity of creative nonfiction. It’s a surprisingly sensitive subject.

Was Steinbeck a dedicated notetaker, such as, we might assume, Hemingway was, having a more extensive journalism background? If Steinbeck wasn’t, or had been but in later years preferred his literary instincts to the rules of journalism, I can almost imagine him trusting the former, feeling he had earned the right, and sometimes getting it wrong or filling the vacuum with fragments of memory.

Those who know me accept that I love and respect the work of John Steinbeck. I am currently reading the Truth behind Travels with Charley and enjoying the experience.

Even Steinbeck acknowledged that his journalistic accountings of characters and events were, in his memory, partially (or completely) products of his imagination, it doesn’t alter my admiration for the man and his work.

In life’s low points, I tend to re-read Steinbeck’s Cannery Row books as they serve as a heart tonic and improve my outlook and attitude. When I read Travels With Charley, especially the accounting of how Steinbeck was treated on the Row on his return with Charley, I realized that his accounting of characters and events in Cannery Row and Sweet Thursday were idealized or romanticized. Even he admitted that the memories he held were altered and he couldn’t distinguish between the actual facts and his memory images, And to me this is okay. Perhaps the improved version of characters and events establishes a higher standard for individuals and society and I support the improvement.

I believe it is important to accept that Steinbeck had no desire to be dishonest in his accounting of events and characters used in his writing. I believe he recognized the difference between writing fiction and writing a journal and did both superbly.

I also believe we should distinguish between “truth” and “facts”. Truth is a personal conclusion. My trutn may not be your truth. Facts are publicly demonstrable and supported with evidence.

I don’t believe anyone should discount the value of Steinbeck’s influence on this world based upon the opinions expressed in the “Truth About Travels With Charley” book. Perhaps he travelled with Charley nearing the end of his life, to compare what he recalled with current observations in his travels.

Personally I shall always be grateful to John Steinbeck, Ed Ricketts, Flora, the Bear Flag, Wing Chongs, and Wide Ida’s for properly adjusting my perspective on life and individuals.

Sometimes We NEED snapshots…..

Sometimes We NEED paintings

Our souls yearn for both