What is there left to say about the complicated life of John Steinbeck? In a blurb for Jackson Benson’s magisterial 1984 biography, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, Steinbeck’s friend John Kenneth Galbraith, the Harvard economist who became John Kennedy’s ambassador to India, claimed that “There will never be another book like it”—adding, “nor will we need one.” The first half Galbraith’s prediction proved to be accurate. Benson—now 90 and Professor Emeritus of English at San Diego State University—began his 16-year project of research and writing on Steinbeck’s life eight months before Steinbeck’s demise on December 20, 1968. In the aftermath of the author’s death, Benson had direct personal access to scores of Steinbeck’s friends, colleagues, and acquaintances, many of whom were dead by the time the next full-scale life of Steinbeck—John Steinbeck: A Biography, by the Middlebury College professor and poet Jay Parini—appeared in England in 1994 and in America in 1995. With its massive assemblage of meticulously researched primary material, Benson’s ambitious life of John Steinbeck is still the source no serious student of the author can afford to ignore.

With its massive assemblage of meticulously researched primary material, Benson’s ambitious 1984 life of John Steinbeck is still the source no serious student of the author can afford to ignore.

Given the scope, depth, and durability of Benson’s accomplishment—and the persistence of Galbraith’s doubt that another book like it was needed—the question of what’s left to say about Steinbeck, 36 years after the publication of The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, is deserving of an answer. Given the complex, controversial, and consequential character of Steinbeck’s life and reputation, the answer to the question is plenty. The reasons for this are both general to biography-writing and specific to Steinbeck studies. In addition to new material not previously available, newly important details may have been slighted or misinterpreted by previous biographers, and the passage of time typically requires a fresh perspective on familiar facts and old assumptions. Even when details of important events and relationships in a subject’s life story are already well-known—as they are with Steinbeck, thanks to Benson—there is the delight of anticipation in recalling them again in a new rendering, much like looking forward to a favorite passage of music when listening to a familiar piece played by a new performer. New biographers, having the advantage of time, can also address the question—especially thorny in the case of a figure like Steinbeck—of how the subject’s critical and popular reputation has fared through the years. Which works have endured and which have lost their relevance for readers? What are the major reassessments, if any, of an author’s writing? Finally, there is the matter of accessibility and appeal in an age, like ours, of short attention spans. Benson’s biography of Steinbeck exceeds 1,100 pages. Parini’s is less than half as long. William Souder’s Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck totals 446 pages, revealing much that was unknown, or off limits, to Benson and Parini.

To its credit, Jay Parini’s life of John Steinbeck included information which was unavailable to Benson or which Benson decided—or was advised—to leave out. Most notable, perhaps, was Parini’s revelation that Steinbeck’s first wife, Carol, had an affair, or at least an intense infatuation, with the future mythologist Joseph Campbell. The beginning of the deterioration in the Steinbeck marriage coincided with Campbell’s 1932 move to Monterey, where the young Ivy League graduate became friendly with the Steinbecks, their boon companion Ed Ricketts, and the bohemian circle that gathered regularly at Ricketts’s marine lab on Cannery Row. Parini reports that Carol, at Steinbeck’s insistence, had a botched abortion that required a hysterectomy, further contributing to the breakdown that led to the Steinbecks’ divorce in 1942. Although the biography adds little to our understanding of Steinbeck’s involvement with Lyndon Johnson and Vietnam in the 1960s, Parini reflects the tenor of the 1990s by offering a more critical appraisal (Steinbeck “fell hook, line, and sinker for an old-style patriotism”) than Benson did a decade earlier.

To its credit, Jay Parini’s 1994 life of Steinbeck included information which was unavailable to Benson or which Benson decided—or was advised—to leave out.

In keeping with greater gender-sensitivity, Parini is also less forgiving of Steinbeck’s treatment of women in the novels and stories, pointing, for example, to the stale stereotyping of women intruding upon an Edenic male world and contributing to its destruction, as Curley’s wife does in Of Mice and Men—stereotyping that was raising eyebrows even before Parini wrote. Without disparaging Benson, reviewers were generally positive about Parini’s book when it appeared, pointing out its appeal—especially to non-academic readers—and praising its economy, pacing, and novelistic approach to Steinbeck’s life. Despite Galbraith’s assessment of Americans’ reading stamina, it seems likely that more non-specialists have been introduced to Steinbeck through Parini’s short life than through Benson’s longer one—until now. Disproving Galbraith’s claim that no new life of Steinbeck would ever be needed, Mad at the World seems certain to join existing biographies on the bookshelves of present and future Steinbeck fans, especially in America, a country whose history pervades William Souder’s writing, as it did Steinbeck’s.

Despite Galbraith’s assessment, it seems likely that more non-specialists have been introduced to Steinbeck through Parini’s short life than through Benson’s longer one—until now.

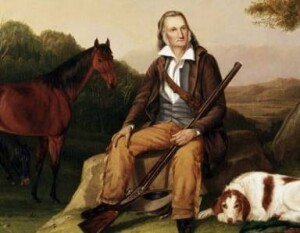

A 71-year-old resident of rural Minnesota who began his career as a journalist reporting on science for the Minnesota Daily, Souder later wrote for major publications including The Washington Post, the New York Times, Smithsonian, and Harper’s. He is the author of three previous books that reflect his interest in science and its intersection with social justice, art, and culture: A Plague of Frogs (2000), Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America (2004—one of only two Pulitzer Prize finalists for biography that year), and On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson, Author of Silent Spring (2012).

A 71-year-old resident of rural Minnesota who began his career as a journalist reporting on science for the Minnesota Daily, Souder later wrote for major publications including The Washington Post, the New York Times, Smithsonian, and Harper’s. He is the author of three previous books that reflect his interest in science and its intersection with social justice, art, and culture: A Plague of Frogs (2000), Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America (2004—one of only two Pulitzer Prize finalists for biography that year), and On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson, Author of Silent Spring (2012).

In a 2015 interview with Steinbeck Now Souder explained that he was conducting research on Ed Ricketts for his book about Rachel Carson when John Steinbeck “found” him while he was reading about the 1940 “voyage of discovery” made by Steinbeck and Ricketts to the Sea of Cortez. As he became more familiar with Steinbeck’s life, he was fascinated by the way Steinbeck’s career “cuts right across the headlong march of 20th century American history. . . . [He was] born just after the close of the Victorian era—and he dies a few months before Neil Armstrong steps onto the moon. So that was his material. I was hooked.” Steinbeck was personally attractive as a subject, says Souder, because he was “far from perfect—as a man, a husband, a writer, he had issues. . . . He had a permanent chip on his shoulder. Some of his work is brilliant and some of it is awful. That’s what you want in a subject—a hero with flaws.” When asked “What does your biography bring to the table?” Souder responded, “My way of telling a story.”

When asked ‘What does your biography bring to the table?’ Souder responded, ‘My way of telling a story.’

Looking for what was causing grotesque deformities in frogs across areas of the northern United States and southern Canada in the mid-1990s, the investigators in A Plague of Frogs confront not only the challenges of ambiguous and contradictory scientific data, but also the roadblocks thrown up by government agencies fearful of the potential economic impact of their inquiry. As in a Steinbeck novel, the investigators are forced to deal with personal and professional conflicts that further complicate their relationship with power. Souder guides the reader through a maze of technical and scientific detail, evoking landscapes and bureaucratic imbroglios with equal drama and transforming what might have become a tedious head-scratcher into a page-turning “what dunnit.”

Looking for what was causing grotesque deformities in frogs across areas of the northern United States and southern Canada in the mid-1990s, the investigators in A Plague of Frogs confront not only the challenges of ambiguous and contradictory scientific data, but also the roadblocks thrown up by government agencies fearful of the potential economic impact of their inquiry. As in a Steinbeck novel, the investigators are forced to deal with personal and professional conflicts that further complicate their relationship with power. Souder guides the reader through a maze of technical and scientific detail, evoking landscapes and bureaucratic imbroglios with equal drama and transforming what might have become a tedious head-scratcher into a page-turning “what dunnit.”

In Under a Wild Sky Souder gives contemporary readers a vivid sense of the pristine beauty of the late 18th and early 19th century American countryside—a world that was already vanishing during Audubon’s lifetime—along with a sense of the challenges of travel and communication in the vast and largely undeveloped American wilderness. Describing the distances between far-flung settlements like Louisville, and the effect of isolation on the domestic lives and the intellectual development of families like the Audubons, Souder helps us understand the lengthy, and to modern minds inexplicable, family separations that characterized the era.

In Under a Wild Sky Souder gives contemporary readers a vivid sense of the pristine beauty of the late 18th and early 19th century American countryside—a world that was already vanishing during Audubon’s lifetime—along with a sense of the challenges of travel and communication in the vast and largely undeveloped American wilderness. Describing the distances between far-flung settlements like Louisville, and the effect of isolation on the domestic lives and the intellectual development of families like the Audubons, Souder helps us understand the lengthy, and to modern minds inexplicable, family separations that characterized the era.

Souder’s attention to Audubon’s rival—a less accomplished artist whose well-connected friends protected his reputation at Audubon’s expense—serves to fill out Souder’s portrait of a rugged artistic genius determined (like Steinbeck) to do things his way and insisting, despite publishers and other doubters, on doing expensive life-sized color images for his magnum opus, Birds of America. Souder captures the contradictions and conflicts of a man who loved animals but shot them, often dozens at a time; who had no qualms about subjecting his dog Dash to an experiment he knew might prove fatal; who, despite his commitment to scientific inquiry, voiced dubious theories and made absurd claims to a prestigious and surprisingly credulous Scottish scientific society. The most ridiculous was a story about a rattlesnake chasing a squirrel up a tree, keeping pace with it as it leapt frantically from branch to branch, and finally catching and swallowing the exhausted critter.

On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson displays the same gift for psychological insight and dramatic presentation, in this case involving the challenges faced by a doggedly determined yet extremely sensitive scientist working for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries during a time of gender inequality, social conformity, and widespread disregard for the dangers of industrial chemicals like DDT applied indiscriminately as pesticides. Rachel Carson was blessed, like John Steinbeck, with a talent for lucid scientific observation rendered in the language of poetry. A woman working in a field dominated by men, she encountered problems peculiar to her situation as an unmarried and unaffiliated agent of social and political change. Like Audubon and like Steinbeck, she was assertive and convincing enough to get her way. In her fashion she defied convention as dramatically as they did, spending the happiest days of her adult life in a long-lasting love affair with a married woman. A masterful blend of empathy and objectivity, Souder’s portrait of Carson foreshadows his psychologically astute treatment of Steinbeck—as an American individualist opposed to those in authority who abuse nature or other people in the name of power or greed.

On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson displays the same gift for psychological insight and dramatic presentation, in this case involving the challenges faced by a doggedly determined yet extremely sensitive scientist working for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries during a time of gender inequality, social conformity, and widespread disregard for the dangers of industrial chemicals like DDT applied indiscriminately as pesticides. Rachel Carson was blessed, like John Steinbeck, with a talent for lucid scientific observation rendered in the language of poetry. A woman working in a field dominated by men, she encountered problems peculiar to her situation as an unmarried and unaffiliated agent of social and political change. Like Audubon and like Steinbeck, she was assertive and convincing enough to get her way. In her fashion she defied convention as dramatically as they did, spending the happiest days of her adult life in a long-lasting love affair with a married woman. A masterful blend of empathy and objectivity, Souder’s portrait of Carson foreshadows his psychologically astute treatment of Steinbeck—as an American individualist opposed to those in authority who abuse nature or other people in the name of power or greed.

A Life-Sized Portrait of a Flawed Hero

Mad at the World opens with a lyrical description of the 90-mile-long coastal California valley between the Gabilan and Santa Lucia mountains where, on February 27, 1902, Steinbeck was born to children of Scots-Irish and English-German immigrants in Salinas, the agricultural town he called home until he left for Stanford in 1919. It is a region remarkable for its sere, rolling hills, rugged mountain vistas, endless fields of lettuce, and pervasive morning fog—in the winter “so dense that you cannot see your feet on the ground,” in the summer a “sea-born fog [that] does not lie still on the land, but seeps over the folded hillsides, rising and falling along the river bottom.” It is country with a storied past, where nomadic Indians ranged for millennia before Spanish explorers arrived, early in the 17th century, in the name of their Christ and their King. When they reached the Salinas Valley they were unimpressed, reporting that its soil was “poor,” its pastures “scant,” and its footing “treacherous.” This proved to be a serious misapprehension about a land where later settlers said “almost anything would grow”—and where generations of agricultural wealth created the power structure Steinbeck complained about, often bitterly, in his writing.

Mad at the World opens with a lyrical description of the 90-mile-long coastal California valley between the Gabilan and Santa Lucia mountains where, on February 27, 1902, Steinbeck was born to children of Scots-Irish and English-German immigrants in Salinas, the agricultural town he called home until he left for Stanford in 1919. It is a region remarkable for its sere, rolling hills, rugged mountain vistas, endless fields of lettuce, and pervasive morning fog—in the winter “so dense that you cannot see your feet on the ground,” in the summer a “sea-born fog [that] does not lie still on the land, but seeps over the folded hillsides, rising and falling along the river bottom.” It is country with a storied past, where nomadic Indians ranged for millennia before Spanish explorers arrived, early in the 17th century, in the name of their Christ and their King. When they reached the Salinas Valley they were unimpressed, reporting that its soil was “poor,” its pastures “scant,” and its footing “treacherous.” This proved to be a serious misapprehension about a land where later settlers said “almost anything would grow”—and where generations of agricultural wealth created the power structure Steinbeck complained about, often bitterly, in his writing.

Mad at the World opens with a lyrical description of the 90-mile-long coastal California valley between the Gabilan and Santa Lucia mountains.

Many of the details of Steinbeck’s childhood are unusual, and Souder parses them carefully, peeling away layers of appearance to reveal how misleading mere facts can be. In his senior year of high school Steinbeck acted in a school play, served as associate editor of the yearbook, ran track, made the basketball team, and became class president. Despite the image of a popular all-American boy suggested by the official record, Steinbeck’s friends from that time remember him as shy, reclusive, and withdrawn. As Souder notes, his election as class president “astonished everyone,” and he never actually played in a basketball game. In fact, he “didn’t like going to ballgames.”

Many of the details of Steinbeck’s childhood are unusual, and Souder parses them carefully.

In his judicious selection of telling details, Souder benefits not only from his own research but also from Steinbeck scholarship in the quarter-century since Parini’s biography. Two books published in the last decade—Susan Shillinglaw’s insightful Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage (2013) and former investigative reporter Bill Steigerwald’s incendiary Dogging Steinbeck: Discovering America and Exposing the Truth about Travels with Charley (2012)—have special bearing on Souder’s reassessment of Steinbeck’s character. Shillinglaw’s study suggests that Carol and John’s lives were even more transgressive and untraditional than previously thought—a view that also emerges in Souder’s portrait. Biographers are allowed to judge, and Souder seems at times to admit being disturbed by Steinbeck’s behavior. He reports “disconcertingly” on the sexual braggadocio regarding Steinbeck’s relations with Carol that Steinbeck employed in his letters to Kate Beswick, a friend and lover from Stanford days. Souder’s response to Steinbeck’s writing to Beswick that his looks were getting worse, but that “my body just now is nearly perfect” is—uncharacteristically—to throw up his hands. “Why Steinbeck kept telling Beswick things like this can’t be explained in any way that makes sense,” writes Souder. “It was simply in his nature.” One thing that can be explained by “things like this” is why Steinbeck didn’t want biographers “mucking around” in his personal life.

Biographers are allowed to judge, and Souder seems at times to admit being disturbed by Steinbeck’s behavior.

It is unlikely that some of the personal details revealed here could have been published earlier—certainly not by Benson and probably not by Parini—even if they were known. Mad at the World is the first major Steinbeck biography published since the death of two surviving members of the Steinbeck family: Steinbeck’s widow Elaine, who died in 2003, and his son Thomas, who died in 2016. Among other disturbing particulars, Souder reports that “Steinbeck forced [Steinbeck’s second wife, Gwyn] to have a number of abortions and had not wanted her to have John IV,” his other son; that John IV at age five got so drunk on champagne at a New Year’s Eve party that he blacked out and woke up the next day “in a little ring of vomit”; and that in his mid-teens John IV “loaded his .22 rifle and held it to the head of one of Gwyn’s boyfriends as they lay drunkenly asleep.” These are the kind of sordid and potentially hurtful details that Jackson Benson removed from the manuscript of his 16-years-in-the making biography, publication of which stalled while lawyers wrangled over objections and possible grounds for litigation raised with Viking Press, which in turn pressured Benson, who vented in his 1988 book Looking for Steinbeck’s Ghost, an account of the interference he encountered in the process of writing the biography that others—not he—claimed was “authorized” by Steinbeck’s family. Benson was understandably embittered by last-minute objections to events which were both true in the telling and, he believed, essential to a full understanding of just how low a point Steinbeck’s life had reached when they occurred.

It is unlikely that some of the personal details revealed here could have been published earlier—certainly not by Benson and probably not by Parini—even if they were known.

Souder devotes two full pages to facts about the writing of Travels with Charley discovered by Bill Steigerwald and revealed in Dogging Steinbeck. In the course of retracing Steinbeck’s 1960 road trip “In Search of America,” Steigerwald demonstrates pretty convincingly that at the very least Travels with Charley is not the nonfictional travel journal that it originally claimed to be. For example, he concludes that in fact Steinbeck “rarely camped in Rocinante, preferring comfortable motels, cozy country inns, and the occasional five-star hotel.” Moreover, he says that for 45 of Steinbeck’s 75 days on the road his wife Elaine accompanied him—decidedly not the impression a reader is left with by Travels with Charley. More troubling for Souder are Steigerwald’s suspicions, mostly buttressed by evidence, that conversations Steinbeck claimed he had with people he supposedly met at key points in the narrative were created from whole cloth—nicely woven, but fabricated from Steinbeck’s imagination.

Souder devotes two full pages to facts about the writing of Travels with Charley discovered by Bill Steigerwald and revealed in Dogging Steinbeck.

Perhaps with Steigerwald’s findings in mind, Souder gives more emphasis than Benson to the claim made by Steinbeck in another work of nonfiction, Sea of Cortez, that, while aboard their research vessel The Western Flyer, Ed Ricketts delivered a monologue on Easter morning which Steinbeck later inserted into Sea of Cortez as the “Easter Sermon.” Benson’s account of the “sermon” quotes a letter Steinbeck and Ricketts sent to Viking to explain the nature of their collaboration on the book they were co-authoring. The letter mentions matter-of-factly that “in one case [in Sea of Cortez] a large section was lifted verbatim from another unpublished work [an essay by Ricketts on nonteleological thinking].” Benson explains that the reference being made is to the “Easter Sermon.” Souder is blunter, calling Steinbeck out for making up facts to suit a fiction by noting that “there was no Easter Sunday Sermon. . . . Steinbeck invented this session, inspired by an unpublished essay by Ricketts on the subject of nonteleological thinking.” He questions other Steinbeck “inventions” as well, though usually in a spirit of sympathy for the creative types who do such things, and with the understanding that Steinbeck naturally inclined toward tall-tale prevarication and embroidery, often but not always in jest. Writers of fiction do, of course “invent things,” but Souder defends Steigerwald, a fellow journalist, by insisting that the author of Dogging Steinbeck “could be forgiven for applying the rules of journalism to a work that purported to be journalism. First among those rules is that facts matter.” His vindication of Steigerwald’s work notes that it mattered enough to Viking’s parent company, Penguin Group, to call for a caveat in Jay Parini’s introduction to the 50th anniversary edition of Travels with Charley: Steinbeck “took liberties with the facts,” admitted Parini, and his book of nonfiction was “’true’ only in the way that a well-crafted novel is true.”

Perhaps with Steigerwald’s findings in mind, Souder gives more emphasis than Benson to a claim made by Steinbeck in another work of nonfiction, Sea of Cortez.

The economy of Souder’s biography in comparison with the books of Benson and Parini has another advantage: dramatic details of character and behavior stand in starker relief when they aren’t crowded by a plethora of other data, however engaging to specialists or essential to scholars of Steinbeck’s life and times. This is not to suggest that Souder is less than scholarly, or that his research was less than thorough. The helpful notes he provides for the 16 chapters in his book span 48 pages, and his index takes up another 15. His acknowledgement of sources is meticulous, his skepticism about received wisdom is healthy, and his interpretations and assessments of Steinbeck’s writings, where given, are sound. Unlike Benson and Parini, he includes a list of works cited—a scholarly desideratum inexplicably missing from their biographies of John Steinbeck.

Dramatic details of character and behavior stand in starker relief when they aren’t crowded by a plethora of other data, however engaging to specialists.

Souder’s treatment of Steinbeck’s character and conduct is sympathetic but not sugar-coated; admiring, but assuredly not adulatory. The portrait that emerges is that of a young boy raised in a proper post-Victorian household, a young church-going Episcopalian who loved his home but remained stubbornly unconventional, even when he behaved. A boy who loved nature and animals but remained aloof from his peers, few of whom could claim to have known him very well. A boy who, in the parlance of the day, would have been called peculiar; a self-styled outcast who preferred the company of other outsiders. A boy with an inner intensity betrayed by a “piercing gaze . . . [which] set him apart even more.” (In a 1981 interview with this reviewer, Steinbeck’s friend Bo Beskow, the renowned Swedish artist who painted three portraits of Steinbeck between 1937 and 1957, recalled his eyes as his most arresting feature.) The well-behaved albeit strange boy with the bright blue eyes developed into a young man whose bohemianism would put the Sixties to shame—a highly successful yet deeply troubled writer whose personal life was frequently in disarray; a deeply sensitive man who could be highly insensitive to others, including family and friends, beset with debilitating self-doubt and afflicted by celebrity which, like Kino’s pearl, proved both a blessing and a curse.

Souder’s treatment of Steinbeck’s character and conduct is sympathetic but not sugar-coated; admiring, but assuredly not adulatory.

Still, Souder’s emphasis on the virtues that attracted him to Steinbeck goes far in explaining why this “hero with flaws” remains more relevant than ever for audiences familiar with the vocabulary and values of environmentalism, equality, and the other causes espoused by Steinbeck in his life and writing. Among those virtues is the sheer variety of Steinbeck’s interests. More than any other major writer of fiction in English in the middle third of the 20th century, Steinbeck made science a pursuit and a cause—one that closely aligned with his phalanx theory of human behavior, developed by analogy with the behavior that he and Ed Ricketts observed in the intertidal organisms they collected and celebrated in the course of their collaboration. Their proto-ecology was prescient, anticipating by two decades the courageous pioneer who gave birth to the modern environmental movement—Rachel Carson. Thanks to their biographer, William Souder, Steinbeck and Carson can be seen as reverse images of one another: Steinbeck the professional writer with a serious interest in science, Carson the professional scientist with a gift for writing that made her a model of graceful style for generations of students versed in the profound simplicity of Silent Spring and Of Mice and Men.

Souder’s emphasis on the virtues that attracted him to Steinbeck goes far in explaining why this ‘hero with flaws’ remains more relevant than ever.

Steinbeck’s anger at social, environmental, and economic injustice resonates with fresh force in the age of COVID-19. As Souder notes in his splendid concluding chapter, a number of Steinbeck’s works are still very much alive today, thanks to their relevance and readability. The creation of memorable characters may be the single most important legacy any storyteller can leave. Whether Steinbeck deserves to be ranked in the company of Dickens, Twain, and Faulkner is a question of individual taste and perception. But like Pickwick, Tom Sawyer, and the Compson clan, Steinbeck’s characters have had a life of their own, beyond the pages of Cannery Row or The Grapes of Wrath. They have survived for the better part of a century and their health remains robust.

Steinbeck’s anger at social, environmental, and economic injustice resonates with fresh force in the age of COVID-19.

Mad at the World is a more than an addendum to the Steinbeck story, challenging Galbraith’s claim that nothing need be written or read after Benson with regard to the life and adventures of John Steinbeck, writer. A brisk and engaging account by a highly-regarded biographer whose estimation of Steinbeck’s importance a half-century after his death is itself testimony to his durability as a writer of fiction and critic of our world. Readers unfamiliar with Steinbeck’s story will come away from Souder’s rendering with a forceful first impression. Those who feel they already know the story well enough can anticipate the pleasure of traveling down a newly-opened road through one’s home town: the general landscape is familiar, but the perspective is novel and the trip its own reward.

Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck will be released by W.W. Norton and Company on October 13.—Ed.

Comprehensive and intriguing piece by Coers, and Souder is a superb writer. But as to the comment “of what’s left to say about Steinbeck,” there will probably aways be something. I have an art gallery in Pacific Grove, California and hardly a month goes by, pre-pandemic and now, that someone doesn’t come in and have a Steinbeck story. Usually that person is elderly. The younger will tell stories passed down by a parent or grandparent, uncle or aunt. The stories seem about 50-50 positive or negative. The negative should probably be taken with a grain, or maybe pound, of salt, because there undoudtedly was a lot of jealousy. The late Monterey writer Jean Ariss (“The Shattered Glass,” which likely mixes fact and fiction from the Steinbeck era), often, tongue in cheek, wonderd aloud how Steinbeck could produce so much great writing “while being drunk all the time.” Earlier this year I was told that “East of Eden” was lifted by Steimbeck from a local man’s private journal. The storyteller swears by it.That was just before the pandemic closed the gallery doors.

I still want to know more – and maybe it is in “Angry at the World” – about why Steinbeck owned so many guns. He described them to Monterey motorcycle cop and friend George Dovolis as a “caboodle” – and in 1942 applied in New York for a license to carry a concealed Colt Automatic. When New York asked if he’d previously had a pistol license, he responded yes, in 1938, which puts him back in California. I attempt to understand the psychology behind what was probably fear in a just-completed play (working title “John and the Oaks”), working backward from the early 1960s to the late 1930s. Of course the play is speculation and fiction based on a few unassailable facts. Kind of fun.

Thanks for your kind words. Your wondering why Steinbeck owned so many guns jolted my memory back to May of 1981 when I interviewed Steinbeck’s long-time friend, the Swedish artist and writer, Bo Beskow. (They first met around 1937-38 in New York.) The interview took place at Beskow’s country home in southern Sweden, my entire visit lasting over twelve hours, during which time Bo’s wife, Greta, occasionally joined us. She was there while we discussed what I’m about to tell you, and backed up and added to what Bo had to say.

I rummaged around in my attic this afternoon and found the notes from that interview. I’m quoting directly from those unpublished notes:

“Steinbeck was very shy, insecure. He also had a complex about Hemingway. Tried to be a sportsman like Hemingway. . . . [He] also bought a gun collection. According to Bo, this was . . . in imitation of Hemingway. He even had a gun room and would oil his guns. Bo: Steinbeck didn’t really shoot. He was copying Hemingway.”

I should add that, despite the closeness of their friendship—they shared many confidences—it was off-and-on. Bo said he would sometimes not hear from Steinbeck for a year or two, then he would call or write or show up somewhere in Europe and want Bo to fly down and meet him at his hotel. The friendship cooled considerably after the Steinbeck’s trip to Sweden to accept the Nobel prize in 1963, so Bo’s remarks to me need to be taken with that in mind.

Also relevant to your wondering about Steinbeck and guns, I recall years ago running across something you are probably already familiar with. I believe it was an article either to or referencing the National Rifle Association—in any event strongly supporting the Second Amendment. A man of many unexpected sides as well as for all seasons.

As you say, there’s still a whole lot out there.

Don, thank you for the great information. I usuallt think of sportsmen with guns having rifles for hunting, not pistols, the latter of which Steinbeck had more than several to judge by his correspondence with George Dovolis. I know Steinbeck had a twenty-two that he might use to scare away birds in Los Gatos – he said he could never shoot them as I recall– because I have seen it. And he supposedly left it with Carol when he traveled and she stayed behind. Anyway, as you say, a complex man. Do you know what caused the fallout between Steinbeck and Bo Beskow?

The fallout between Steinbeck and Beskow, like so many such cases, has, from what I know, several causes primarily personal and political. First, Beskow really liked Carol. In fact, he told me in 1981 that he was still corresponding with her. He did not like Gwyn and didn’t care much for Elaine. He was also disturbed by what he thought perceived as Steinbeck’s insensitivities. For example, when Steinbeck phoned him in the spring of 1952 and asked him to fly down to Spain and visit him and Elaine, whom he had not yet met. Steinbeck was staying in a five-star hotel. Bo had to stay in a much humbler place across the street. Steinbeck called his friend an “introverted snob” who didn’t want to admit how much he enjoyed luxury. Beskow had the impression that it never occurred to Steinbeck that he couldn’t afford anything better. In any event, Beskow said that maybe what he called the “death push” to their close relationship began that spring of 1952.

Their political view also began to diverge around this time. Beskow thought that Steinbeck resorted to patriotic cant when he responded to an open letter written by an Italian communist named Ezio Tadei, and published in the Italian communist newspaper L’Unita. Tadei asked Steinbeck why he did not distance himself from American soldiers’ brutality in Korea. Steinbeck’s answer defended our soldiers, saying among other things, that “they were our beloved sons who are torn from our hearts in a land that needs them” and concluding that if Taddei thought that American soldiers were evil, then he was a “liar.” Beskow believed that Steinbeck had gone very pro-American in the fifties because he was frightened by Joseph McCarthy. And later he was, predictably, critical of the “silly things” Steinbeck said about American involvement in Viet Nam. Finally—and this came from Elaine, not Beskow—there were problems between the two during the time the Steinbecks were in Stockholm for the Nobel ceremonies in December of 1962. Beskow said that he had met the Steinbecks at the Arlanda Airport “with open arms.” But he also called that meeting “the last blaze of a smoldering friendship.” He said that they simply did not “travel through life in the same manner any longer.”

Elaine’s account of their interaction with Beskow during their time in Stockholm is filled with details that Beskow does not mention. She said that he basically horned in on them and their activities: “Guess who was the elbow to everybody”! She said Beskow’s intrusiveness got so problematical that the protocol official assigned to the Steinbecks, a man named Stig Ramel, later CEO of the Nobel Foundation, approached the Steinbecks and asked whether there was anything they could do to help with a delicate situation: Beskow, said Ramel, was creating all kinds of difficulties by trying to act as stage manager for the Steinbecks—which, of course, was Ramel’s job.

After that the two men never saw each other again. “The contact,” Beskow said, was “broken.” Late in 1968 Beskow said he reread some of Steinbeck’s letters and felt a sudden need to reach out to him and talk about how meaningful their friendship had been to him and to ask forgiveness if he had let Steinbeck down. He mailed the letter the second week of December.

Don, the reltionhip of Steinbeck and Beskow, tying in with the other people you mention – especially Carol and Elaine – sounds like a play. It would be helped by all the drama going on in the world at that time, from McCarthy to Korea to Stockholm. I can see actors on opposite sides of the stage, sitting on stools, getting up and pacing, trying to figure out what had happened. One of them Steinbeck, the other Beskow, of course. It is a fascinating story. Thank you.

Interesting and perceptive that you see the drama in the relationship between Steinbeck and Beskow over the 32 years they knew each other as having the essential elements of a play. In fact, Beskow himself treated the drama that unfolded over the years between him and Steinbeck and Steinbeck’s three wives in a fairy-tale-style story he shared with me in 1981 titled “Of wifes and man [sic].” Beskow casts Steinbeck as the king and himself as the court jester.

With his usual lucidity, Don Coers makes a strong case for reading William Souder’s new and much-awaited biography. I look forward to doing so in the near future and hope to come way enlightened, as I have been by Souder’s books on Audubon and Carson. Viva Steinbeck for being a writer who so resoundingly stands the test of time and changing cultural fashions!

Great to hear from you again, Bob. When I first saw your comment, it was on my phone and I read “lucidity” first as “lunacy” then as “acidity” before I fetched my specs. So a lot of time has indeed passed! Hope you and yours are all well and safe. Still in Athens? And are you still fly fishing in the Northwest?

I wonder when Mr. Coers was last in the Salinas Valley. His reference to “…endless fields of lettuce…” is now, unfortunately, no longer as true as it was a few years back. Two or three years ago, lettuce was replaced as the valley’s Number One crop by strawberries. From any elevated point of view, what one now sees on the valley floor are thousands of acres of plastic sheeting. The furrows are created by tractors, the sheeting laid by machine, and the millions of strawberry plants maintained by field workers. If seen at certain angles, these fields appear as enormous reflective seas. The plastic serves to retain moisture and, if I remember correctly, insecticide or fertilizer can be kept from spreading away from the fields. I’ve been told that the majority of the berries are shipped to Japan

After harvest, I’ve seen truckloads of used, dirty plastic sheeting being hauled away to somewhere. We can only hope that it will be recycled.

One other major development that I’ve watched in my 52 years in the Valley, is the spectacular growth of the wine industry, nonexistent in Steinbeck’s time. This has largely occurred in the foothills which are too irregular for row crops. In 1969, I had dinner with a couple of lettuce-cauliflower growers. They were discussing a friend who had decided to try to create a vineyard along the edge of the Valley. They discussed the initial cost of planting the grapes (I think they said $7,000 an acre, which, at that time, was more than my annual salary as a teacher). They were concerned that it might then take three to five years before they could harvest any grapes. They were not enthusiastic. Today the vineyards are visible all the way down the valley as well as over the Santa Lucias in Carmel valley.

Dear Mr. Bartoletti:

I’ve been to Salinas, three times: twice in the seventies, and then again in 1992, so it has indeed been quite a while since I last laid eyes on the landscape there. Interestingly, the crops are following the cash where I live as well–in the Central Texas town of Kerrville, near Fredericksburg and the LBJ Ranch. The region has seen significant growth in wineries over the past couple of decades or so, and that growth is continuing. Last Tuesday, in fact, a small community near us voted to allow sales of wine and liquor, following indications that a winery wanted to establish vineyards and wine-sampling establishments there. The votes, not surprisingly, also following the cash!

Thanks for your comments,

Don Coers

Thank you for this really insightful overview and comparison of the various Steinbeck biographies!

I wanted to love this new biography so much and I did learn a few things about Steinbeck, but ultimately Souder’s tone is so informal and rushed that I finished the book feeling like I still don’t know enough about Steinbeck or so many of his books. At points in reading the biography I was actually shocked at how little time Souder spent on a particular work. I was disappointed that Souder makes too little use of the vast scholarly work on Steinbeck to analyze more about the works in the context in which they were written.

It’s disappointing that this biography is so hyped up due to the gap between this and Parini’s work, but something is still missing from Souder’s biography. I was READY for a 600-page meaty intellectual biography of Steinbeck, in the style of Robert Richardson’s “Emerson: The Mind on Fire,” or, more recently, Ruth Franklin’s biography of Steinbeck’s near-contemporary, “Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life.” I wanted MORE but Souder leaves us hanging.

Dear Ms. Wayne:

Thanks for your thoughtful appraisal of Souder’s Mad at the World. I really like your final sentence: “I wanted MORE but Souder leaves us hanging.” Happily, for in-depth and intellectually hungrier-than-average readers like you there is, as you are well aware, plenty more to satisfy, and thus we might even consider Souder’s contribution as at least a successful appetizer for tasty courses to follow—Benson, Parini, and Sue Shillinglaw’s Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage for starters. All show various sides and angles of an unusually multi-faceted personality and from the perspectives of thoughtful writers with different backgrounds and of several generations. My gut instinct is that Steinbeck would appreciate your appetite, which surely attests to his timelessness—and thus indirectly to the value of new assessments of his literary worth and ongoing philosophical relevance.

By the way, I appreciate your mentioning the recent Franklin bio of Shirley Jackson. Few works that I used to teach back in my English professor days evoked more student fascination than “The Lottery.” Makes me want to be back in the classroom to find out how today’s students would respond to its themes in our interesting times (and yes, I intend the ancient Chinese diplomatic sense of that term).

All best, Don Coers