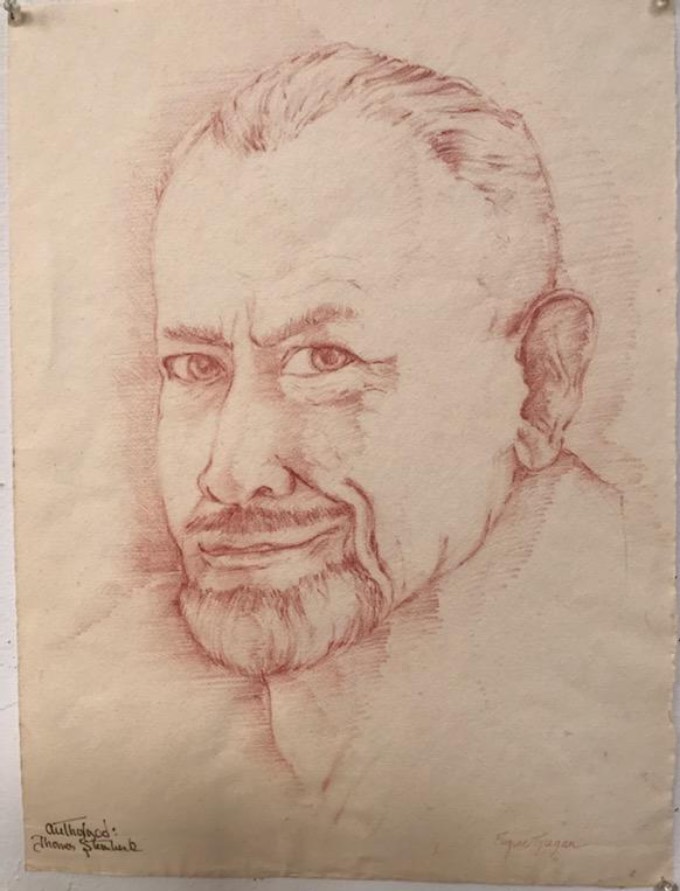

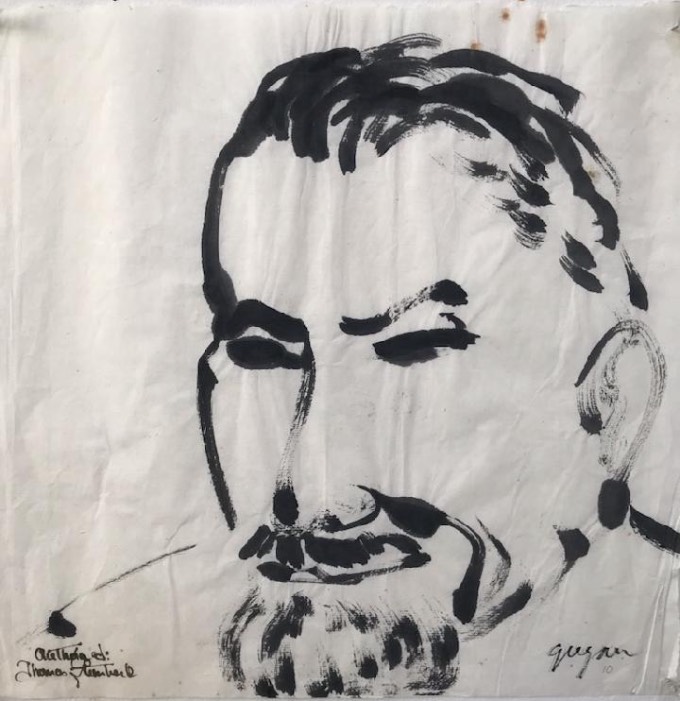

A photograph Thom Steinbeck admired of his father inspired the expressive, high-energy Sumi ink brush painting of John Steinbeck seen here. It’s by the American artist Eugene Gregan and was done in the early 1980s. “Thom showed me the photograph and asked if I would do a drawing from it,” recalls Gregan. “Thom liked the drawing, and that led to a series of Sumi ink portraits.”

Sumi ink is made from natural substances mixed with gelatin and is traditionally used by artists in China and Japan. One of Gregan’s spontaneous ink portraits, this one from life, was of Thom Steinbeck himself. As in the Sumi ink portrait of the elder Steinbeck, it exudes vitality and passion. (Note Thom’s approving inscription in the lower left corner: “Authorized: Thomas Steinbeck.”) Gregan, who knew Elaine Steinbeck but not John, is a student and teacher of Oriental brush painting. The portraits were created, he said, on specially ordered “beautiful handmade paper from China.”

Thom Steinbeck may have liked the photograph, the initial drawing, and the Sumi portraits because his father looks ready for battle in all of them, though much more so in the Sumi versions. This Steinbeckian force had already inspired Gregan. “I saw John Steinbeck introduce one of his movies on television a long time ago,” he says. I got more out of that than anything—his presence was monumental. He had that powerful voice and personality. And so did Johnny and Thom.”

Eugene Gregan and the Commune at Lookout Farm

Gregan and Steinbeck’s sons, John Ernst Steinbeck IV (whom Gregan refers to as Johnny) and Thomas Myles Steinbeck, were friends for years. Gregan, who is 84, remained close to the brothers from just after the end of the Vietnam War until their deaths. He feels that both participated in the war to please their father. “We all lived in the same commune in the Catskills,” remembers Gregan. “A place we called Lookout Farm. I moved up from Brooklyn. There were a lot of interesting people in the area, including Ram Dass.” Adds Gregan: “Johnny built a sound studio there, and Thom, who was also a talented designer, designed a scale model of the Swiss Family Robinson house for Walt Disney—it was the model for the structure subsequently constructed at Disneyland.”

Gregan and Steinbeck’s sons, John Ernst Steinbeck IV (whom Gregan refers to as Johnny) and Thomas Myles Steinbeck, were friends for years. Gregan, who is 84, remained close to the brothers from just after the end of the Vietnam War until their deaths. He feels that both participated in the war to please their father. “We all lived in the same commune in the Catskills,” remembers Gregan. “A place we called Lookout Farm. I moved up from Brooklyn. There were a lot of interesting people in the area, including Ram Dass.” Adds Gregan: “Johnny built a sound studio there, and Thom, who was also a talented designer, designed a scale model of the Swiss Family Robinson house for Walt Disney—it was the model for the structure subsequently constructed at Disneyland.”

Energized by communal life, the three friends joined forces to try to make films of John Steinbeck stories. But they soon realized, after knocking on producers’ doors, that the project wouldn’t succeed without name directors or actors backing it. The Steinbeck name alone was not enough. So when Thom wrote a screenplay treatment of The Pearl, he managed to get it to a name director: Steven Spielberg. “The screenplay was absolutely fabulous,’’ Gregan recalls. “Spielberg liked it but said the young boy couldn’t die at the end in the film—typical Spielberg.’’ Thom Steinbeck wasn’t willing to compromise.

Johnny died in 1991, Thom in 2016. Gregan said he and Thom ”closed’’ a lot of New York bars over the years. “He could light up a place with his presence. He was a great story teller.’’

Eugene Gregan studied under Josef Albers and Norman Ives at Yale and taught at the Rhode Island School of Design. He has exhibited internationally. Collectors of his work have included Miles Davis, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Robert Mitchum, Ram Dass, Judd Hirsh, Julie Christie, and Calvin Klein. His home today is not far from the old commune in the mountains. There he continues to paint while work proceeds on a film documentary of his life. His wife Beverly keeps a famously beautiful garden known to inspire poets and painters—including, of course, Gregan. He has a saying: “Invest in beauty. It is a great antidote to fear.” That beauty can include Sumi ink brush paintings of gardens, landscapes, and people—including a couple of expressively energized Steinbecks.