Near the end of Travels with Charley, John Steinbeck celebrates the inspiring courage of Ruby Bridges, the six-year-old schoolgirl who advanced the cause of civil rights by breaking the Southern segregation barrier at a New Orleans elementary school 56 years ago. San Jose State University will honor Bridges’s lasting contribution to civil rights on February 24 by conferring the Steinbeck “In the souls of the people” Award—a program of the school’s Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies—on the 61-year-old author, activist, and advocate, who has been called the first foot soldier in the modern civil rights movement.

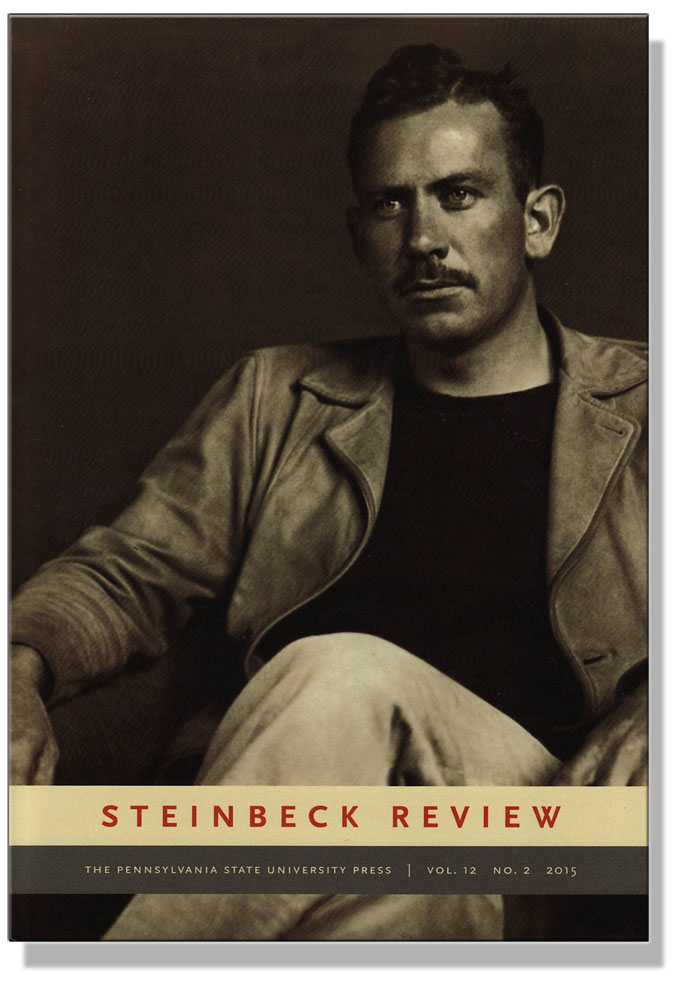

Steinbeck wrote Travels with Charley in sadness, and occasional shock, at the state of America in 1960, when he was 58, and he chose the South as the last stop on his journey of rediscovery and reconciliation because he recognized racism and civil rights as the fundamental conflict to be resolved if the country he loved was to survive. Watching grown white women curse the diminutive black girl entering William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans turned his stomach, as it did Americans reading newspaper accounts of the widely reported event. Though Ruby Bridges isn’t identified by name, Travels with Charley captures her image, braving the kind of mob Steinbeck depicted better than anyone, like a contemporary news photograph:

The big marshals stood her on the curb and a jangle of jeering shrieks went up from behind the barricades. The little girl did not look at the howling crowd but from the side the whites of her eyes showed like those of a frightened fawn. The men turned her around like a doll, and then the strange procession moved up the broad walk toward the school, and the child was even more a mite because the men were so big. Then the girl made a curious hop, and I think I know what it was. I think in her whole life she had not gone ten steps without skipping, but now in the middle of her first skip the weight bore her down and her little round feet took measured, reluctant steps between the tall guards. Slowly they climbed the steps and entered the school.

Thanks in part to Travels with Charley, Ruby Bridges became an icon of civil rights for succeeding generations—a platform she has used brilliantly as a writer and speaker to advance the values of tolerance, understanding, and equality embraced by Steinbeck in his time. “John Steinbeck expressed concern over an injustice and wrote sympathetically of me when I was a young girl,” she explains. “In a way, we’ve come full circle. I now get to honor him by receiving an award bearing his name. I’m so proud to be part of this.”

Ruby Bridges will speak and accept the Steinbeck Award a public event—“An Evening with Ruby Bridges”—beginning at 7:30 p.m. on February 24 in San Jose State University’s Student Union Theater on the school’s downtown San Jose, California campus. Tickets are available at the Event Center Box Office (408-924-6333) or at Ticketmaster.com.