David M. Wrobel—Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Oklahoma University, President-Elect of the Western History Association, and Visiting Scholar at the National Steinbeck Center—recently spent a busy week in Salinas, California speaking to audiences young and not-so-young about John Steinbeck’s war reporting in World War II and, 20 years later, in Vietnam. On September 5 Wrobel explored the question of the century—“Who was John Steinbeck?—with an energetic group of fifth and sixth graders from schools named for famous figures, including John Steinbeck, Cesar Chavez, and Oscar Loya, the former superintendent of schools for the district settled by “Okies” and others, east of Salinas. On September 6 he met with John Wood’s English class at Everett Alvarez High School, then led discussion of Steinbeck’s controversial career as a war correspondent at the National Steinbeck Center—a presentation which he repeated the following day at the Monterey Public Library. Wrobel holds the Merrick Chair in Western American History at the University of Oklahoma, but he discovered Steinbeck as a British school boy growing up in London council housing. Though an Englishman explaining Steinbeck to Californians might sound a bit like bringing coals to Newcastle, Wrobel’s enthusiasm is infectious, as shown in this photo of his reception by American school children assembled for the purpose in Steinbeck’s home town.

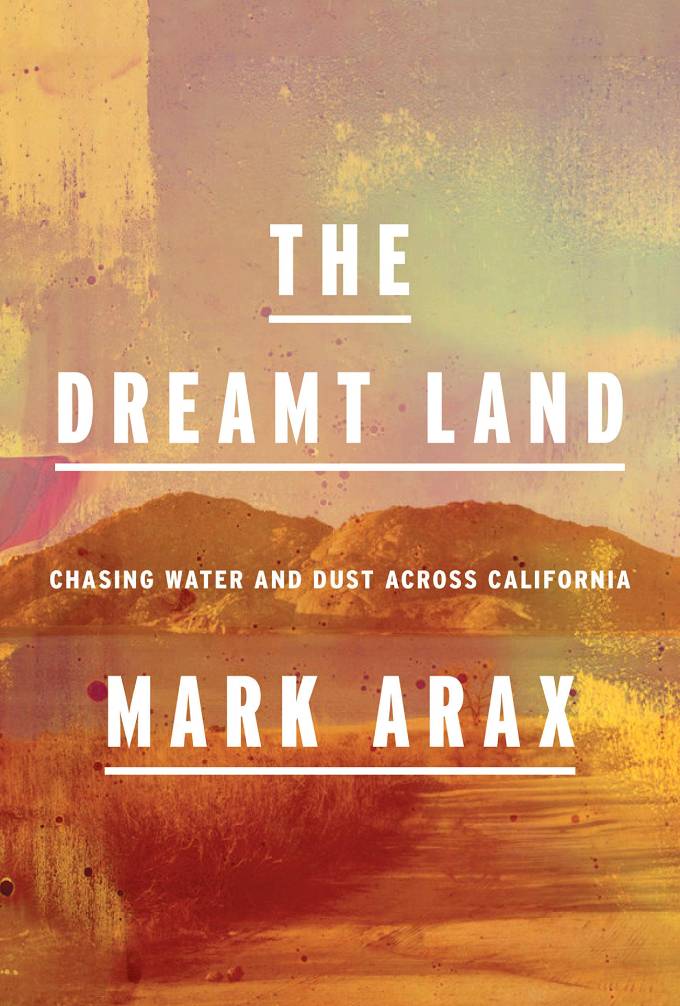

The Ghost of John Steinbeck Inhabits The Dreamt Land

The spirit of John Steinbeck haunts the world of Mark Arax, the award-winning author and journalist from Fresno, California whose latest work—The Dreamt Land: Chasing Water and Dust Across California—continues the investigation of land abuse and human tragedy in California’s Central Valley that began with The King of California: J.G. Boswell and the Making of a Secret American Empire (2003) and remains, like Steinbeck’s style of dudgeon in The Grapes of Wrath, both detached and intensely personal. A restless son of Fresno’s substantial Armenian community, Arax first reported on Central Valley life for the Los Angeles Times while pursuing the people behind his father’s 1972 murder in the 1996 memoir, In My Father’s Name, that made Fresno feel more like Blue Velvet, the 1986 movie by David Lynch, than The Human Comedy, the 1943 novel by Steinbeck’s contemporary and the Arax family’s neighbor William Saroyan. Like The King of California (co-authored with Times colleague Rick Wartzman), Arax’s third book—West of the West: Dreamers, Builders, and Killers in the Golden State (2009)—followed the founding crimes of overbuilding, exploitation, and genocide from their roots in Gold Rush greed to the case of “The Last Okie in Lamont,” the Central Valley town that stimulated Steinbeck’s spleen in The Grapes of Wrath. A splendid sequel to West of the West, The Dreamt Land is Arax’s longest book to date, and—for fans of Steinbeck’s ghost—his finest.

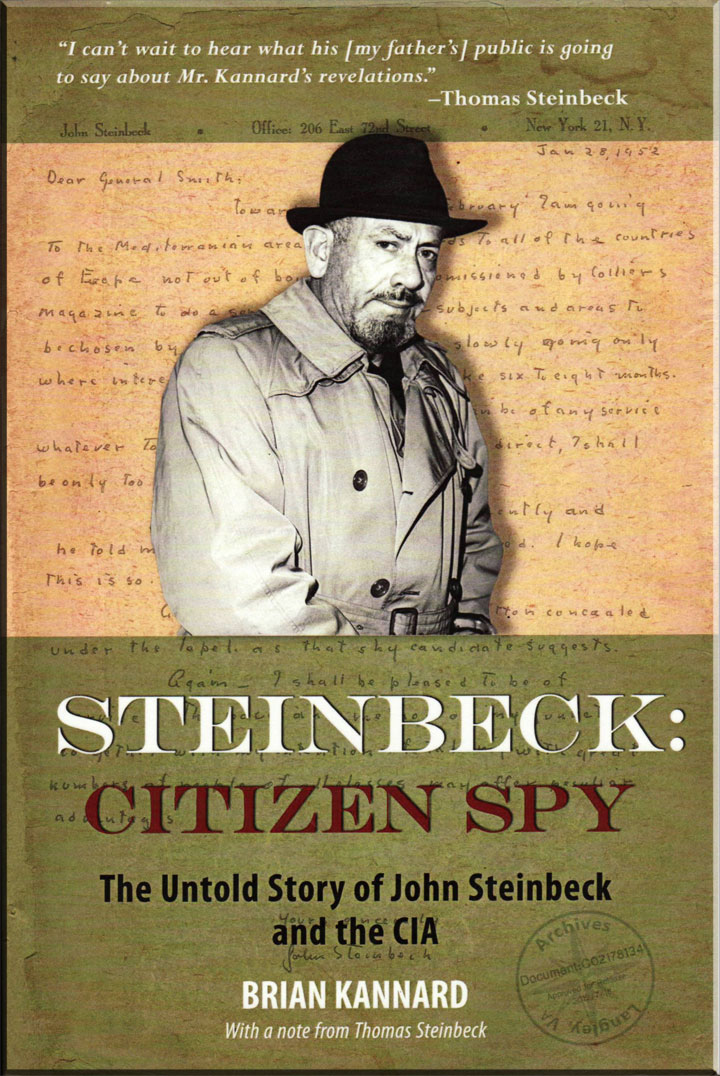

Christopher Dickey Asks: Was John Steinbeck a CIA Informant in Paris in 1954?

Was John Steinbeck acting as a CIA informant in Paris the summer he wrote the satirical short story for Le Figaro, published in English for the first time in the current issue of The Strand, about a haughty French chef and his hyper-finicky cat? That’s the question raised in a provocative Daily Beast piece by Christopher Dickey, the Daily Beast’s Paris-based world-news editor. Working his way to a firm maybe, Dickey quotes John Steinbeck’s contemporaneous correspondence with his New York agent, Elizabeth Otis, and Thom Steinbeck’s eye witness account—first cited by Brian Kannard in his 2013 book Steinbeck: Citizen Spy—of daily visits to the Steinbeck’s residence at 1 Avenue de Marigny by a man from the U.S. embassy with an attaché case. The son of a famous father, like Thom Steinbeck, Christopher Dickey is a frequent contributor to Foreign Affairs, Vanity Fair, The New York Times, MSNBC, CNN, France 24, BBC TV, and Al Jazeera.

1954 Short Story by John Steinbeck Written in Paris Published by The Strand

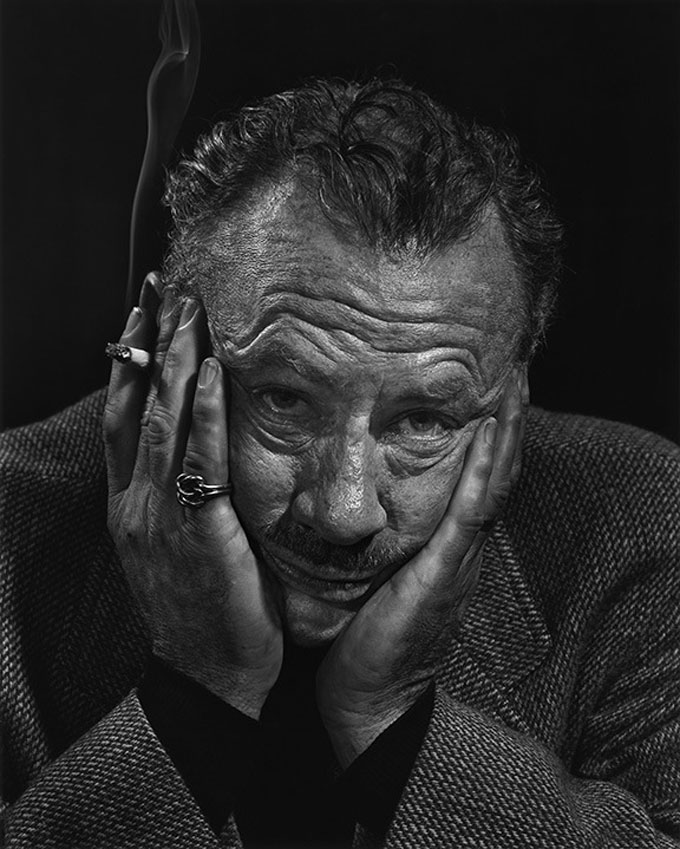

The current issue of The Strand Magazine features a fun find—the English version of a whimsically satirical short story John Steinbeck wrote for the Paris paper Le Figaro, where it appeared on July 31, 1954 as Les Puces sympathiques. An expression of the Gallic wit exemplified by Steinbeck’s 1936 short story Saint Katy the Virgin and his 1957 novel The Short Reign of Pippin IV, “The Amiable Fleas” recounts a tragic-comic contretemps involving Monsieur Amité, a nervous French chef, and Apollo, his temperamental cat. The tongue-in-cheek item about the publication of the short story in today’s Guardian newspaper—“Crêpes of wrath: unknown John Steinbeck tale of a chef discovered”—quotes this understatement by the magazine’s enterprising editor, Andrew Gulli: “Don’t expect to read something dramatic in the vein of Grapes of Wrath.” According to The Guardian, Gulli found the manuscript among the Steinbeck holdings at the University of Texas, where he also came across the typescript of the Steinbeck sketch titled “With Your Wings”—written for radio broadcast in 1943-44 and published by The Strand in 2014. The Yousuf Karsh photograph above was taken at the Steinbecks’ residence in Paris about the time Steinbeck was writing “The Amiable Fleas” for Le Figaro, where he was a regular contributor, frequent interviewee, and favorite American.

New Light on John Steinbeck at Stanford’s Green Library

A trove of documents donated to Stanford University—the S.J. Neighbors collection of John Steinbeck papers, 1859-1999—adds dramatic detail to a literary life story that started in 19th century Germany and Palestine and became synonymous with 20th century California and America. Totaling 256 items, the acquisition is the largest since 1999, when Wells Fargo funded the addition of a major collection of Steinbeck material to the holdings of the newly renovated Green Library, which first opened in 1919, the year Steinbeck enrolled at Stanford as a freshman. The new collection includes correspondence to and from John Steinbeck, notebooks kept by his American grandmother, Almira Steinbeck, and lecture notes written by her earnest, German-born husband about their missionary work in Palestine and the attack on their compound in Jaffa that sent them packing for the United States, just in time for the outbreak of the Civil War. According to Rebecca Wingfield, curator of British and American literature, the addition of the S.J. Neighbors collection makes the Stanford University Library the most important resource anywhere for research on Steinbeck’s roots. Her colleague Ben Stone, curator of American and British history, notes that the school’s commitment to Steinbeck includes access to the collection by regular readers of the restless American writer who never got around to telling his grandparents’ back story and disappointed his family by leaving Stanford without a degree.

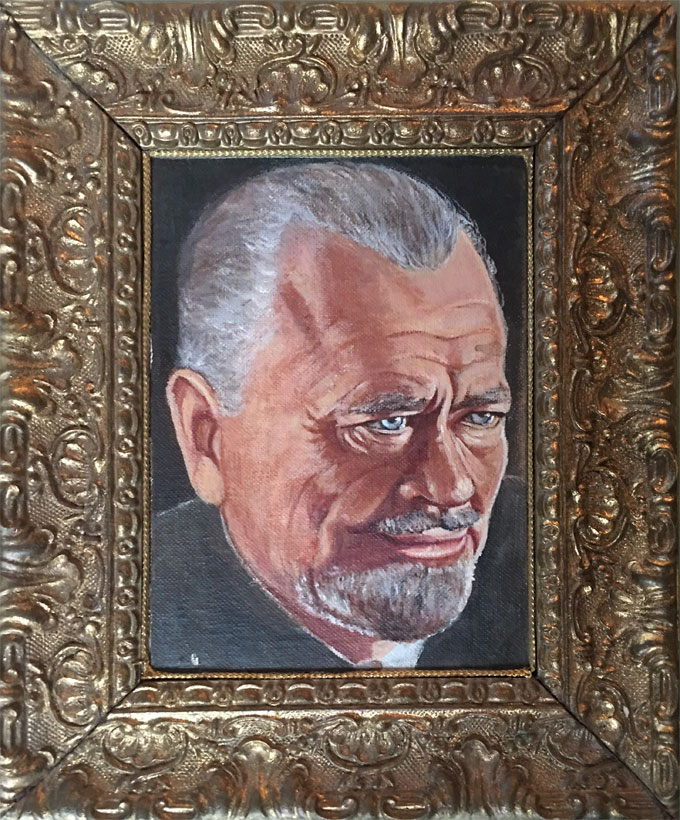

Painted 50 Years Ago, Lost Portrait Comes to Light

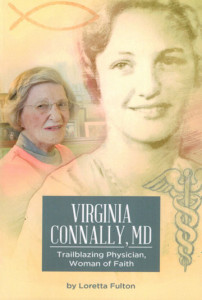

The lucky purchase by a young couple in Austin, Texas—of a lost portrait of John Steinbeck painted by an admirer 50 years ago—presents intriguing questions about the California author’s connection to Texas, the state he celebrated in Travels with Charley because, he said, his wife Elaine grew up there. Anthony Verdecanna, a specialist in mid-20th century furniture, and his wife Whitney, a musician, came across the elegantly framed find recently at an estate sale near Austin. The inscriptions on the back—“To Elaine Steinbeck” and “Virginia Boyd in Thailand 1969”—piqued their curiosity about its provenance. Following the trail of “Jenny Boyd,” the person who signed the work, they learned that the Virginia in the inscription was most likely the artist’s mother, Virginia Hawkins Boyd Connally, a pioneering physician in Abilene and the widow of Ed Connally, chairman of the Texas Democratic Party during the heyday of Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson. An eye-ear-nose-and-throat specialist whose first husband

The lucky purchase by a young couple in Austin, Texas—of a lost portrait of John Steinbeck painted by an admirer 50 years ago—presents intriguing questions about the California author’s connection to Texas, the state he celebrated in Travels with Charley because, he said, his wife Elaine grew up there. Anthony Verdecanna, a specialist in mid-20th century furniture, and his wife Whitney, a musician, came across the elegantly framed find recently at an estate sale near Austin. The inscriptions on the back—“To Elaine Steinbeck” and “Virginia Boyd in Thailand 1969”—piqued their curiosity about its provenance. Following the trail of “Jenny Boyd,” the person who signed the work, they learned that the Virginia in the inscription was most likely the artist’s mother, Virginia Hawkins Boyd Connally, a pioneering physician in Abilene and the widow of Ed Connally, chairman of the Texas Democratic Party during the heyday of Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson. An eye-ear-nose-and-throat specialist whose first husband  was named Fred Boyd, Dr. Connally was born in 1912 and died on March 31, 2019, leaving her daughter Genna Boyd Davis, an art education major in the 1960s, as her sole immediate survivor. Like a story by Steinbeck, the heroic narrative of Virginia Connally’s life presents multiple possibilities. Did she and Ed meet John and Elaine in Texas through the Johnsons, with whom the Steinbecks were friendly? Or was the writer’s generous portrait of Texas in the pages of Travels with Charley enough to win her affection—and the tribute of a devoted daughter’s painting, lost for 50 years until its discovery by yet another power couple from Elaine Steinbeck’s home state?

was named Fred Boyd, Dr. Connally was born in 1912 and died on March 31, 2019, leaving her daughter Genna Boyd Davis, an art education major in the 1960s, as her sole immediate survivor. Like a story by Steinbeck, the heroic narrative of Virginia Connally’s life presents multiple possibilities. Did she and Ed meet John and Elaine in Texas through the Johnsons, with whom the Steinbecks were friendly? Or was the writer’s generous portrait of Texas in the pages of Travels with Charley enough to win her affection—and the tribute of a devoted daughter’s painting, lost for 50 years until its discovery by yet another power couple from Elaine Steinbeck’s home state?

Burning Issues Keep Name John Steinbeck in the News

The 80 year milestone of John Steinbeck’s best seller, the Holy Week fire that burned through Notre-Dame in Paris, and civic controversies in Sag Harbor sent a crowd of commentators scurrying back to their copies of The Grapes of Wrath, published on April 14, 1939, and The Winter of Our Discontent, the 1961 novel Steinbeck set during Holy Week and over July the Fourth in mid-century America. The self-explanatory title of an edgy piece by Nicolaus Mills—“Why Steinbeck’s Masterpiece is Disturbingly Relevant to Trump’s America”—appeared on the Daily Beast politics site on the eve of the anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath. “A Song Calling to a New Day”—a more serene appreciation of the novel—posted from the Zen priest James Ford at Monkey Mind, a Buddhism blog site, at the same time. “Seeking redemption a timeless tale”—an April 20 Tulsa World column by Ginnie Graham—drew on Notre-Dame, Dickens, and Steinbeck to look on the bright side of things, followed by a less sanguine piece in the McAlester News-Capital—“’The Grapes of Wrath’ begins in McAlester”—reminding readers that the governor of Oklahoma officially disinvited Steinbeck to their state in 1957. A review of James Agee’s 1951 novel Morning Watch by one Joseph Bottum posted at the right-wing news site Washington Free Press on April 20, recommending The Winter of Our Discontent as appropriate Holy Week reading for unhappy conservatives. The stew in Sag Harbor over a pothole believed to be mentioned in Steinbeck’s novel got the satire it deserved in a May 5 write-up in Dan’s Papers—“Sag Harbor Considers John Steinbeck Memorial Pothole Solutions”—that proved Steinbeck’s point about humor’s superiority to holiness.

Photograph by Christian Delbert courtesy Dan’s Papers.

Exhibit, Conference Show Steinbeck is in Good Hands

The local link between Ludwig van Beethoven and John Steinbeck, a man who loved Broadway but preferred Bach, gave minds at San Jose State University—where the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies shares space with the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies—the bright idea for The Art of Biography, an exhibit of images and objects from the two collections that runs through July 6, 2019 on the fifth floor of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library. Timed to coincide with the 2019 Steinbeck conference, held May 1-3, the exhibit’s Steinbeck content was created by Alexandra Mezza and Allison Galbreath, graduating students in the MFA creative writing program directed by Nick Taylor, who also serves as director of the Steinbeck center.

The local link between Ludwig van Beethoven and John Steinbeck gave San Jose State University the idea for an exhibit of images and objects from the two collections.

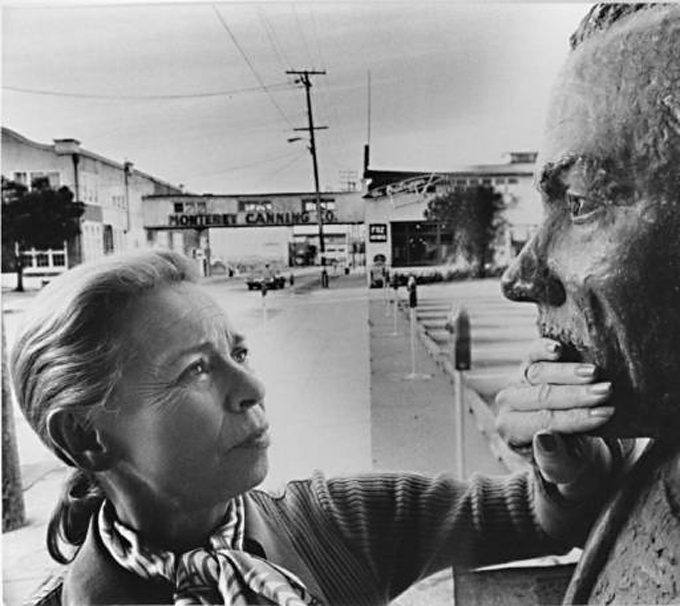

Like this exhibit photo of Elaine Steinbeck, taken at Cannery Row in 1975, the 2019 conference field was dominated by women with a special touch for John Steinbeck. Speakers included Mary Papazian, the Milton scholar who became San Jose State University’s president since the last Steinbeck conference was held three years ago; Noelle Brada-Williams, the new chair of the university’s English department; Susan Shillinglaw, English professor and author of the artful biography, Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage; Marisa Plumb, also of the English department; Barbara A. Heavilin, professor emeritus at Taylor University and editor-in-chief of Steinbeck Review; Mimi Gladstein, the University of Texas, El Paso, superstar who writes about Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Faulkner’s women; Cecilia Donohue, a retired professor of English at Madonna University; Elisabeth Bayley, who teaches at Loyola University in Chicago; Aya Kubota, a professor at Japan’s Bunka Gakuen University; Lori Newcomb, a teacher at Wayne State College; Naama Cohen of Tel Aviv University; Danica Cerce, a member of the faculty of the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia; Debra Cumberland, a teacher at Winona State University; Robin Provey, a graduate student at Western Connecticut State University; Jennifer Ren, an entering law student at the University of Houston; and Audry Lynch, the veteran educator from Boston who had the unusual experience of interviewing each of Steinbeck’s three wives in California.

Like the exhibit photo of Elaine Steinbeck taken in 1975, the 2019 conference field was dominated by women with a special touch for John Steinbeck.

Women also filled the stage for after-hour attractions during the conference. Three 2018-19 Steinbeck Fellows in Creative Writing at San Jose State University—Katie M. Flynn, Kirin Khan, and Christine Vines—read from their fiction on opening night. When the formal program closed on Friday, 20 of 50 conference attendees boarded the bus for Salinas, where Susan Shillinglaw led a look-and-listen tour that included the Red Pony Ranch, the Steinbeck House, and the National Steinbeck Center, where Michele Speich—a nonprofit professional from Monterey—recently succeeded Shillinglaw as the Salinas organization’s executive director. Steinbeck House dinner was served by members of the Valley Guild, the group of mostly female volunteers who bought the home in the 1970s and pay the bills by running the restaurant and encouraging donations. If Martha Heasley Cox had such women in mind for the future of John Steinbeck’s legacy when she started the center that bears her name, also in the 1970s, today’s results would have to make her happy.

Photograph by John Bryson courtesy of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies.

William Souder Booked for 2019 Steinbeck Conference

William Souder—the Minnesota journalist whose book-length lives of John James Audubon and Rachel Carson established his reputation as an ecology-minded biographer with a nose for the human back story—will discuss the art of biography, and his upcoming life of John Steinbeck, as featured speaker for the 2019 International Steinbeck Conference, May 1-3, at San Jose State University. “The Subject is Steinbeck: Thoughts on the Theory and Practice of Biography” may sound academic as a title for the talk, but Souder as a speaker rarely does—as demonstrated by this 2016 interview, in which he explains how writing about Audubon, Carson, and a plague of frogs led him to undertake the first major life of Steinbeck in 25 years. Scheduled for publication in the summer of 2020, when environmental collapse and humanitarian crisis are destined to dominate the most divisive presidential election news cycle since 1968, Souder’s biography of an author who stayed “angry at the world” for most of his life is likely to make literature newsworthy again by connecting books, as Steinbeck did, to burning issues.

A Night at Madison Square Garden with John Steinbeck

“Revisiting the American Nazi Supporters of ‘A Night at the Garden’”—Margaret Talbot’s political think piece in this week’s New Yorker—raised the intriguing question posed by Robert DeMott in an email to Steinbeck fans today. Was John Steinbeck aware of the racist rally that attracted 20,000 Hitler fans to Madison Square Garden, the midtown Manhattan building where he’d once done grunt work, on February 20, 1939? Even in California, it’s hard to imagine he wasn’t, despite being otherwise engaged at the time worrying about his novel The Grapes of Wrath, which came out two months later. World War I had sensitized Americans with German names like Steinbeck to issues of loyalty and ethnicity, and anti-New Deal attacks on The Grapes of Wrath included criticism from Americans convinced that Steinbeck and Roosevelt were both Jewish names. Talbot says the Nazi movement in the United States was saved from itself by Pearl Harbor, and that raises another intriguing question for Grapes of Wrath fans. Without the jobs or moral clarity created by World War II, would folks like the Joads have sided with liberals like Steinbeck, or with the pro-Nazi crowd at Madison Square Garden in 1939? As this film of the event shows, it looked a lot like the kind of rally where Americans like the Joads are expressing their enthusiasm for Donald Trump in 2019.

Photograph courtesy Marshall Curry / Field of Vision