Mexico was a magnet for John Steinbeck, a frequent visitor and sympathetic observer who explored the threats posed by assumptions he questioned to a culture he admired in fiction (The Pearl), film (The Forgotten Village), and history (the writer’s superbly researched introduction to Viva Zapata!). Fresh evidence that the feeling was mutual can be found in Steinbeck y Mexico: Una Mirada Cinematografica en la Era de la Hegemonia Norteamericana by Adela Pineda, Associate Professor of Spanish at Boston University and Director of Latin American Studies Program at Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies. “Steinbeck’s engagement with the history and the cinematic archive of revolutionary Mexico took place in an embattled field of political and cultural activity on both sides of the Río Grande, hence it could not be but complex and contradictory,” explains Pineda, winner of the Malcolm Lowry Fine Arts Literary Essay Award from the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes for Las Travesías de John Steinbeck Por México, El Cine y Las Vicisitudes Del Progreso. Pineda’s archival research revealed “the many facets of Steinbeck as a novelist, scriptwriter, film collaborator, and public intellectual”; writing a book about “Steinbeck going global from the vantage point of Mexico” is a fitting tribute to an admiring author whose research into a vanishing way of life became material for enduring art.

Why Cultural Appropriation Is Much Worse than Alcohol

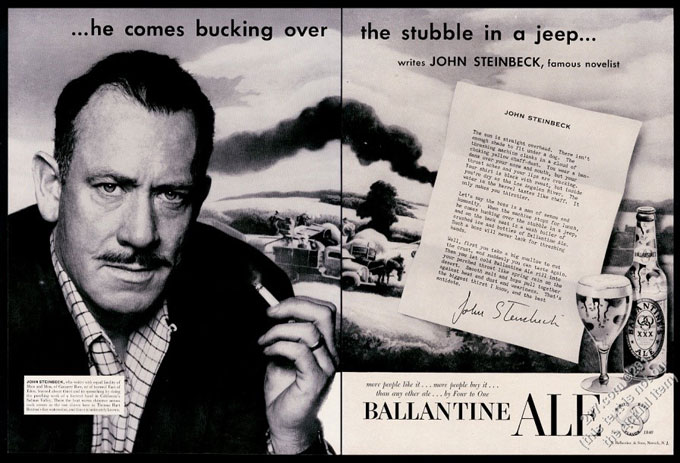

Identity politics aside, quoting John Steinbeck out of context is an act of cultural appropriation calling for correction when the interest being served is one Steinbeck criticized in his writing. Ballantine Ale benefited from his endorsement in this 1953 advertisement, true, but the author of The Grapes of Wrath distrusted big business and condemned consumerism in Travels with Charley and The Winter of Our Discontent. “If I wanted to destroy a nation,” he confided to Adlai Stevenson in 1959, “I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy and sick.” Forbes magazine had been defending corporate power and prestige for decades when Steinbeck wrote his letter to Stevenson, and our so-called business president began his career as a serial liar by gaming his score on the magazine’s annual wealthiest-list in the 1980s. Reason enough to object to today’s cultural appropriation of John Steinbeck’s advice to budding writers by the expert who posted “How to Use Targeted Content Marketing to Gain More Customers” at the magazine’s online edition for budding entrepreneurs: “Remember that great outreach is an act of storytelling. As author John Steinbeck wrote, “Forget your generalized audience. In the first place, the nameless, faceless audience will scare you to death and in the second place, unlike the theater, it doesn’t exist. In writing, your audience is one single reader.” If you wanted to destroy a nation in 2018, having Donald Trump for president and Forbes magazine for literary light would be a sobering way to start.

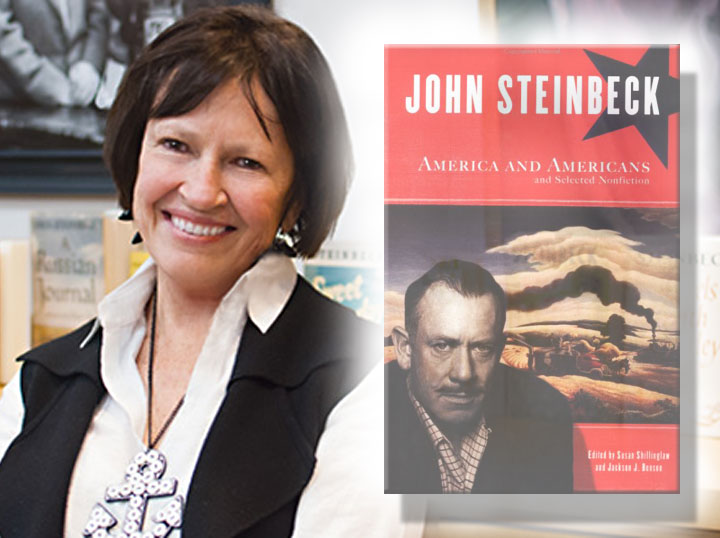

John Steinbeck’s Women in Sag Harbor and Salinas

The village setting of The Winter of Our Discontent closely resembles Sag Harbor, the Long Island town where John Steinbeck liked to loaf and write, and the women in The Winter of Our Discontent reflect aspects of the women in Steinbeck’s personal life, the focus of the 2018 Steinbeck Festival in Salinas, the California town where the author of The Winter of Our Discontent grew up with a sister named Mary and a girl from church who went on to marry a man named Hawley. Susan Shillinglaw wrote the introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of The Winter of Our Discontent and conceived of the idea for this year’s Steinbeck festival, so there’s a pleasant symmetry to the May 18-20 celebration of the novel being planned in Sag Harbor, where Shillinglaw (in photo) will lead public discussion and the book will be read aloud, cover to cover, at Canio’s Cultural Café. Salinas and Sag Harbor were bookends in the life of John Steinbeck. So were the trio of Marys from Steinbeck’s family and the family of the novel’s hero Ethan Hawley—Steinbeck’s beloved sister; Ethan’s steadfast spouse, and the enlightened daughter who prevents his discontent from becoming despair. The temptress in Ethan Hawley’s tale also has a correlative in Steinbeck’s personal history. To find out who she was, sign up for the May 4-6 celebration of The Women of Steinbeck’s World and note whose name is missing from the honor roll. If Long Island is more convenient, show up for the May 18 talk by Susan Shillinglaw, the link between Steinbeck’s Sag Harbor and Salinas, and ask.

Art of the River That Runs Through Steinbeck’s World

John Steinbeck’s love affairs with women, the fine arts, and the Salinas River valley come together at the 2018 Steinbeck Festival in Salinas, California when the artist and writer Janet Whitchurch talks about Underground and Running North, a new fine art book featuring her images and text. Sponsored by the National Steinbeck Center, “The Women of Steinbeck’s World” runs Friday, May 4 through Sunday, May 6 in Salinas, Monterey, and Pacific Grove and includes daytime lectures and tours, after-hour social events, and an art-feature talk by Whitchurch about the local river that inspired her book—and, like the women in his world, both inspired and frightened John Steinbeck, whose lifelong love affair with fine art and writing was fortunately less ambivalent. Don’t miss out on the variety and fun. Purchase your ticket today.

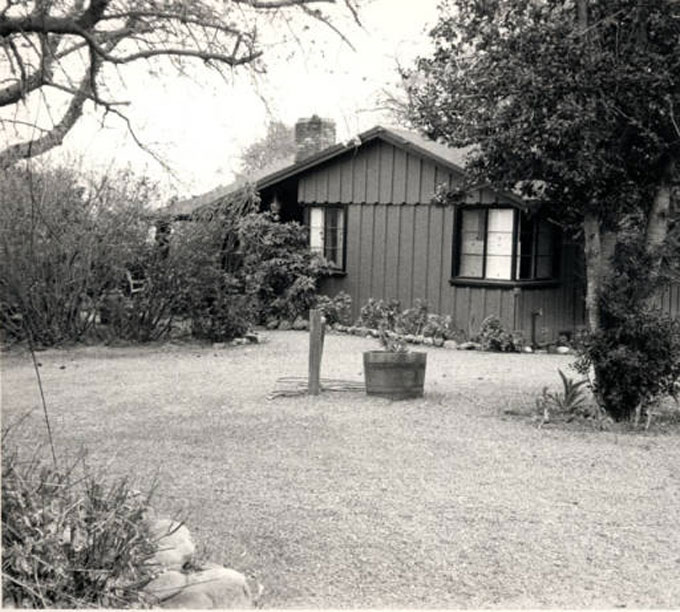

Not John Steinbeck’s View

Purple sofas, 4,000 square feet, and an elevated view of midtown may make the New York apartment where John Steinbeck died in 1968 a bargain at $5 million, as asserted in the sale listing for 190 East 72nd Street, but the stark contrast with Steinbeck’s unvarnished view of the world in 1938 will not have escaped thoughtful readers of The Grapes of Wrath. A house is not a home if you’d rather be somewhere else, and Steinbeck preferred the little getaway he and his wife Elaine bought way out on Long Island because he preferred small towns, small houses, and doing his writing without a distracting view, however elevated. When Elaine Steinbeck died, new owners doubled the space of the apartment and added bedrooms and bathrooms (six of each) but kept the roll-top desk used by Steinbeck and offered as part of the sales pitch. But a sales picture is worth a thousand words. Compare the hard lines and assertive scale of the souped-up, for-sale living room, with its massive, grape-purple sofas and $5-million view, and the solitary appeal of the modest house where Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath—an unvarnished depiction of the stark contrast, then and now, between people with no home and those who live in glass houses but insist on throwing stones.

Photo of John Steinbeck’s Santa Cruz mountain home courtesy Los Gatos Public Library

Looks Like Tom Joad and Sings Like Woody Guthrie

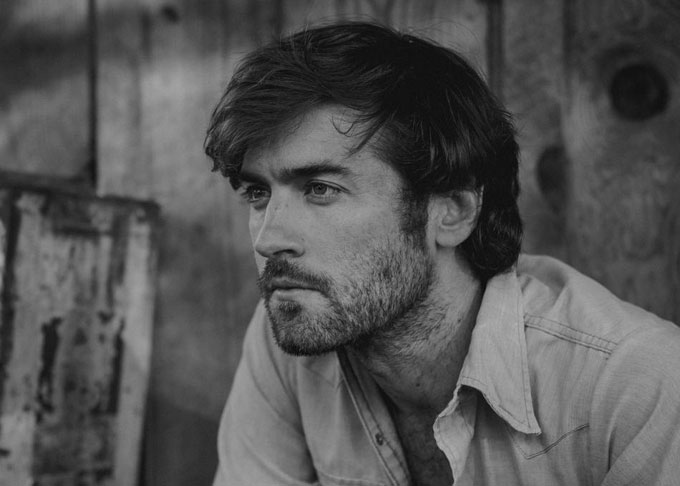

John Craigie speaks from experience about the title of his recently released tour recording John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. The soft-spoken West Coast singer-songwriter explains that performing as a warm-up act is like “having to read a short story by another author before getting to a work by John Steinbeck,” an artist who understood the perils of playing second fiddle. A born-and-bred Californian with the face of a sweet Tom Joad and the voice of a young Woody Guthrie, Craigie combines folk music, stand-up comedy, and situational storytelling to elicit the kind of audience response espoused by Steinbeck from listeners—to judge from the live recording—who are with him all the way on the perils of presidents named Trump and books named Leviticus. “The storytelling enables listeners to relate,” says Craigie, who majored in math at UC-Santa Cruz and got his start singing and playing in a band called Pond Rock. “Really good music doesn’t make you feel good,” he adds, echoing John Steinbeck on why he wrote fiction. “It makes you feel like you’re not alone.” Sample the track, then buy a signed CD of John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. (Photo of John Craigie by Bradley Cox)

John Craigie speaks from experience about the title of his recently released tour recording John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. The soft-spoken West Coast singer-songwriter explains that performing as a warm-up act is like “having to read a short story by another author before getting to a work by John Steinbeck,” an artist who understood the perils of playing second fiddle. A born-and-bred Californian with the face of a sweet Tom Joad and the voice of a young Woody Guthrie, Craigie combines folk music, stand-up comedy, and situational storytelling to elicit the kind of audience response espoused by Steinbeck from listeners—to judge from the live recording—who are with him all the way on the perils of presidents named Trump and books named Leviticus. “The storytelling enables listeners to relate,” says Craigie, who majored in math at UC-Santa Cruz and got his start singing and playing in a band called Pond Rock. “Really good music doesn’t make you feel good,” he adds, echoing John Steinbeck on why he wrote fiction. “It makes you feel like you’re not alone.” Sample the track, then buy a signed CD of John Craigie Live: Opening for Steinbeck. (Photo of John Craigie by Bradley Cox)

Why We Don’t Delete Facebook But You Should

If the medium is the message, what does Facebook’s demeanor say about its dependent users? I don’t have boundaries—or enough to do to fill my time? I don’t have real friends, so pokes, shares and likes from fake ones fill my need to feel in touch? I don’t care if they sell my information because convenience is more important to me than privacy? Much as wish we could, we won’t delete Facebook from this website’s social media menu because some readers still use it to receive weekly post updates. But if you’ve tried reaching out to us there, we apologize for the inconvenience. We don’t respond to pokes and messages because we never liked the look and feel of the platform, or its potential for addiction and abuse. As explained in today’s report in The Hill on Facebook’s misappropriation of user data, recent events have confirmed our worst suspicions. If you decide to delete Facebook in protest, SteinbeckNow.com applauds you. You’re sending a message that the author who always preferred privacy to convenience would no doubt approve. Let us know when you do . . . but don’t use Facebook.

A Pilgrim’s Progress for Students of John Steinbeck

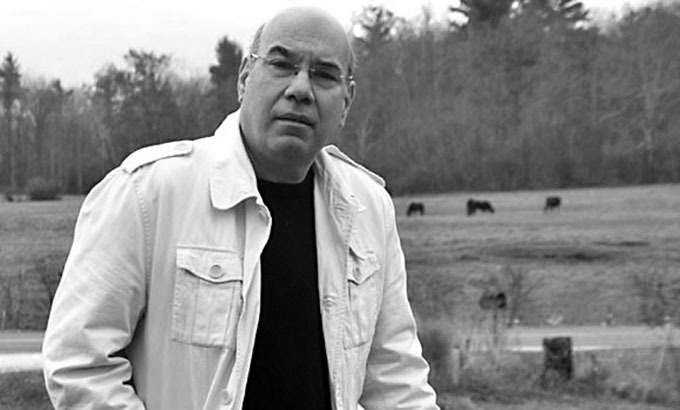

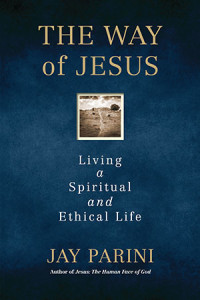

John Steinbeck studied Pilgrim’s Progress at his mother’s knee. Literally. John Bunyon’s allegory of sin and salvation was still family reading when Olive Steinbeck taught her pre-school son the alphabet 100 years ago and home libraries like the Steinbecks’ had books like Pilgrim’s Progress, so essential to Christian living that they were read aloud at family gatherings like the Bible. Like his father, John Steinbeck was often depressed about life, and Bunyon’s Slough of Despond colored his dark view of home town Salinas, a place of sloughs in both senses of Bunyon’s word—“swampy” and “characterized by lack of progress.” Like his mother, he had conflicting views about religion, “a curious mixture [for her, he said] of Irish fairies and an Old Testament Jehovah.” Her parents were frontier Calvinists, but she sent her son to the Episcopal church, where he stayed, nominally, until he died. He told his physician that he didn’t believe in an afterlife, but he wanted an Episcopal church funeral anyway and his fiction is full of religion gleaned from books he read in childhood—the Bible, Pilgrim’s Progress—and mined for material in books still read today. Fortunately for readers without grounding in Steinbeck’s religion, Steinbeck’s biographer Jay Parini (in photo) has provided a Pilgrim’s Progress for the post-Christian century in The Way of Jesus, a spiritual autobiography by a gifted writer that also serves as a reader’s guide to Christianity in the spirit of Steinbeck’s fiction—progressive, companionable, and inviting participation.

The Way of Jesus: A Better Way to Understand Belief

Like John Steinbeck, Jay Parini found refuge in the Episcopal church from the fundamentalism of puritanical forebears. Like William Faulkner and Gore Vidal, authors whose lives he chronicled after writing about Steinbeck, Parini is a working novelist with a foot in the film world and—like Robert Frost, another subject—a people’s poet with a Vermonter’s view of America. He teaches creative writing at Middlebury College, and The Way of Jesus is a teaching book with all the traits of a well-taught course. A second-semester sequel to Parini’s life of Jesus with a literary approach to scripture and belief, it explores the poetry of T.S. Eliot and the aggregation of writings we call the Bible with equal agility. Designed for readers without special knowledge, its explanation of esoteric topics like Christian liturgy, Calvinist theology, and the church year—features of Steinbeck’s fiction from Tortilla Flat to The Winter of Our Discontent—is abundantly clear and courteous to newcomers. The ease and efficiency will appeal to students, and the extra equipment, including source documentation, will please their professors. Happiest of all will be fans of literature (if not religion) who love somebody else’s story when it involves them and invites action, like Steinbeck at this best.

Like John Steinbeck, Jay Parini found refuge in the Episcopal church from the fundamentalism of puritanical forebears. Like William Faulkner and Gore Vidal, authors whose lives he chronicled after writing about Steinbeck, Parini is a working novelist with a foot in the film world and—like Robert Frost, another subject—a people’s poet with a Vermonter’s view of America. He teaches creative writing at Middlebury College, and The Way of Jesus is a teaching book with all the traits of a well-taught course. A second-semester sequel to Parini’s life of Jesus with a literary approach to scripture and belief, it explores the poetry of T.S. Eliot and the aggregation of writings we call the Bible with equal agility. Designed for readers without special knowledge, its explanation of esoteric topics like Christian liturgy, Calvinist theology, and the church year—features of Steinbeck’s fiction from Tortilla Flat to The Winter of Our Discontent—is abundantly clear and courteous to newcomers. The ease and efficiency will appeal to students, and the extra equipment, including source documentation, will please their professors. Happiest of all will be fans of literature (if not religion) who love somebody else’s story when it involves them and invites action, like Steinbeck at this best.

Doctors and Empathy: East of Eden Makes Medical News

Bedside manner works both ways. When John Steinbeck was hospitalized halfway through 1968, his doctor Denton Cox wrote on his chart, “The patient has sent me to Ecclesiastes,” a biblical book with the stoical view that the ultimate antidote for suffering is surrender. The physician followed the advice and Steinbeck was sent home, where he died in December. “What do I want in a doctor?” he asked in a letter he wrote to Cox at the beginning of their relationship: “Perhaps more than anything else—a friend with special knowledge.” Explaining his disbelief in “a hereafter” in clinical terms of “experience, observation and simple tissue feeling,” he went on to defend euthanasia, insisting “that the chief protagonist should have the right to judge his exit” when the time comes to let go and die. East of Eden, like Ecclesiastes, is a quotable book, and one medical news source says physicians should be more like Cox and pay attention to its message of empathy. A February 28, 2018 editorial in Medical News Report—a proprietary publication of Healthline Media UK Ltd.—quotes East of Eden to help contemporary healthcare professionals understand how empathy differs from sympathy, and why John Steinbeck continues to require medical attention, though of a different sort, today.

John Steinbeck on Social Media; Trump on Twitter

We thought tweets were only for twits like the “Hemingway of Twitter” who currently resides in the White House. Riane Konc, the bright young humor writer seen here who introduced John Steinbeck to the world of social media with great success, has made us think again. In a February 16, 2018 interview about the popularity of her comic blog posts and social-satire tweets, she explained: “To be extremely specific, I think I am at my top functioning when writing a 600-800-word piece where the central joke is something about John Steinbeck. I have, so far, tricked three entire publications into publishing my Steinbeck jokes, which feels way too high.” “Excerpts from Steinbeck’s Novel About the Drought of 2013-2017,” Konc’s pitch-perfect parody of The Grapes of Wrath, appeared at NewYorker.com in July, followed by “A Mommy Message Board Dissects the Ending of The Grapes of Wrath,” a send-up of faux social media communities, at PasteMagazine.com. “Season’s Greetings from the Steinbeck Family!”—Konc’s Christmas Letter from Steinbeck Land (“It has been another dry and brutal year in the Salinas Valley”)—was published in December and reposted at Reddit, where it attracted a thread of clever responses from literate fans (“Our youngest, John Jr., is an exceptional student and was given responsibility for the class pet, a turtle. We were not surprised when it died, for the crops were bad that year.”) A former English teacher who admits that “Twitter has indisputably lowered my quality of living,” Konc says she was gratified nonetheless when “thousands of people on Twitter decided that they were going to riff on a William Carlos Williams poem for several weeks.” Great. But Donald Trump is still riffing, too.