My most recent trip to the Monterey Peninsula as Visiting Scholar at the National Steinbeck Center was organized to further the Center’s connection to the increasingly diverse community of Monterey County and Salinas, California. Speaking at the Center about John Steinbeck’s career as a war correspondent in the context of the exhibit on Steinbeck at war was a real treat, as were my talks to John Wood’s high school English class in Salinas and the audience—mostly adult—attending a Saturday afternoon session at the Monterey Public Library. As a faculty member and administrator at Oklahoma’s largest public university, I make it a point to meet community groups whenever I can, and the individuals I encountered at each stop on my Monterey Peninsula itinerary came with interesting questions and intelligent insights about the author who helped make the region a literary legend. The library in Monterey is the oldest public library in California, and John Wood’s students are writing research papers on John Steinbeck, who attended high school in Salinas and college at Stanford. But the highlight of the trip was the time I spent with the youngest people on the schedule—fifth and sixth graders from area schools named for Cesar Chavez, John Steinbeck, and Dr. Oscar Loya, former superintendent of the Alisal school district east of Salinas. The kids’ energy was contagious, and their questions kept me on my toes most enjoyably. Their teachers and principals thanked me for coming, but on reflection the greater pleasure was mine. Helping to make John Steinbeck’s life and work relevant in children’s lives today can be a heady experience—one I recommend to those who, like me, research and write about John Steinbeck as faculty members at institutions of higher learning from Oklahoma to California.

Test Drive John Steinbeck’s America and Leave Feedback

Early in 1938, as Steinbeck began writing The Grapes of Wrath at his home in the mountains, he was nervous about doing justice to an American tragedy unfolding in real time: the flight of desperate farm families from the Dust Bowl states of Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas to the Promised Land of California. “I’m trying to write history while it is happening,” he explained in a letter to his agent Elizabeth Otis, “and I don’t want to be wrong.” In the spring semester of 2017 I taught a course on John Steinbeck’s America that showed how right he was. It resulted in a new author website devoted to the world that John Steinbeck critiqued and created.

Twenty-three upperclassmen and two graduate students (one from Poland) enrolled for the course, offered in the University of Oklahoma’s College of Arts and Sciences. They came from Biology and Psychology and Letters as well as English and History, the departments in which it was cross-listed for credit. They read a variety of John Steinbeck’s works and discussed them within the context of American history and current events. They wrote papers on Steinbeck’s travels and wartime writing, works on stage and screen, Oklahoma, and East of Eden. They created the website introduced here for the first time for your comment.

The effort had excellent support. Mette Flynt, a PhD candidate in History, helped tighten prose, ensure accuracy in citations, and achieve consistency of language and layout. Paul Vieth, an MA student in History of Science, assisted with the Resources and Research page. Sarah Clayton—the University of Oklahoma Libraries staff member who won a national award for her innovative work with digital humanities course initiatives like this one—provided the class training in website construction using Omega, an open-source publishing platform. You can help by test driving the site and making suggestions.

Go to John Steinbeck’s America and give us your feedback in the comment box below.

Grapes of Wrath Views from the University of Oklahoma: Two Photographers, Two Novels, and Two Migrations

The day after John Steinbeck’s recent birthday, I spoke to an audience at the University of Oklahoma in Norman, where I teach, about three forgotten stories behind the writing, impact, and unintended consequences of The Grapes of Wrath. The occasion was an exhibition of works by the Great Depression photojournalist Horace Bristol, one of Steinbeck’s collaborators in the run-up to The Grapes of Wrath.

The day after John Steinbeck’s recent birthday, I spoke to an audience at the University of Oklahoma in Norman, where I teach, about three forgotten stories behind the writing, impact, and unintended consequences of The Grapes of Wrath. The occasion was an exhibition of works by the Great Depression photojournalist Horace Bristol, one of Steinbeck’s collaborators in the run-up to The Grapes of Wrath.

The venue was the Fred Jones Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma, which figures significantly in the narrative behind John Steinbeck’s novel. Steinbeck may not have visited the state before he wrote The Grapes of Wrath, but Oklahoma cared deeply about his work—and not just in the negative way portrayed by the press. Closer consideration of John Steinbeck, his collaborators, and his fictionalized migrants seemed appropriate in preparing my talk as I contemplated the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath. What I uncovered wasn’t new but hidden. Here is a summary of my remarks to my University of Oklahoma audience.

Unequal Collaborators: John Steinbeck and Horace Bristol

Traveling on weekends on assignment for Life magazine from the end of 1937 to March 1938, Horace Bristol accompanied John Steinbeck to migrant camps in California’s Central Valley. The Steinbeck-Bristol partnership proved less than equal. Bristol needed the collaboration with Steinbeck more than the writer needed the photographer.

In Dubious Battle, the 1936 novel in which Steinbeck charted the anatomy of a Central Valley fruit pickers’ strike, hit sore nerves at both ends of America’s political spectrum and attracted noisy criticism from communists and conservatives alike. In August he moved on to the San Joaquin Valley to examine the living conditions of California migrant workers and their families for the left-leaning San Francisco News. His hard-hitting account of the struggle for survival of Great Depression migrants from the country’s ravaged heartland was serialized in the paper under the title “The Harvest Gypsies.” It was reprinted (with an additional chapter) in pamphlet form by the Simon J. Lubin Society in 1938 under the title Their Blood is Strong, with revenues going to migrant relief.

The Steinbeck-Bristol partnership proved less than equal. Bristol needed the collaboration with Steinbeck more than the writer needed the photographer.

Steinbeck’s 1937 novella Of Mice and Men—the searing story of the daily labors, fragile hopes, and ultimate tragedy that befall the itinerant ranch hands George and Lennie—became a national sensation; the New York stage version played to critical acclaim and ran for more than 200 performances. Clearly, Horace Bristol saw the professional benefits of collaborating with John Steinbeck, despite differences. Like the writer, however, the photographer was drawn on a deeply personal level to the suffering migrants they observed living in tents, makeshift shacks, and broken down vehicles, hidden along California’s byways and back roads.

The Horace Bristol-John Steinbeck collaboration for Life resulted in unforgettable examples of Great Depression photojournalism. But Bristol’s goal for the project—a book of his photographs accompanied by Steinbeck’s text—never materialized. By late May, Steinbeck had begun the hectic hundred days of writing that produced The Grapes of Wrath: Steinbeck’s sprawling manuscript, completed in November, was published in April 1939 to acclaim and attack. Clearly, one reason the Bristol-Steinbeck partnership never achieved full fruition is that Steinbeck was too busy writing his novel and dealing with the celebrity and controversy that ensued.

But there is another reason: John Steinbeck could be an undependable collaborator. A proposed partnership with the photojournalist Dorothea Lange, whose pictures of Great Depression migrants deeply moved the author, also failed to materialize. And there was a third reason, too: Life refused to publish the text written by Steinbeck to accompany Bristol’s photographs. Although some of Bristol’s pictures appeared, the author’s language was too liberal for the magazine’s conservative tastes. John Steinbeck’s relationship with the Time-Life publishing empire never recovered; almost without exception, his books were panned by Time’s reviewers, despite the Pulitzer Prize he received for The Grapes of Wrath and the Nobel Prize for Literature he was awarded in 1962.

John Steinbeck could be an undependable collaborator. A proposed partnership with the photojournalist Dorothea Lange, whose pictures of Great Depression migrants deeply moved the author, also failed to materialize.

It is also worth noting that, while Steinbeck appreciated the visual arts and understood the power of words wedded to images, as a writer he may have doubted that documentary photography was the most desirable medium to illustrate his powerful prose. Indeed, as pointed out by James Swensen—whose manuscript “Picturing Migrants” is scheduled for publication by the University of Oklahoma Press—the 1939 dust jacket of The Grapes of Wrath featured, not a real-life image by Bristol, Lange, or any of the other Farm Security Administration photographers documenting the Great Depression in disturbing detail, but a made-to-order painting by the commercial illustrator Elmer Hader. To the chagrin of Ron Stryker, head of the Historical Section of the Farm Security Administration, the deluxe two-volume version of The Grapes of Wrath published in 1940 by Viking Press featured a series of paintings by the Midwestern artist Thomas Hart Benton, not the photographs of Bristol, Lee, or Lange.

As a writer he may have doubted that documentary photography was the most desirable medium to illustrate his powerful prose.

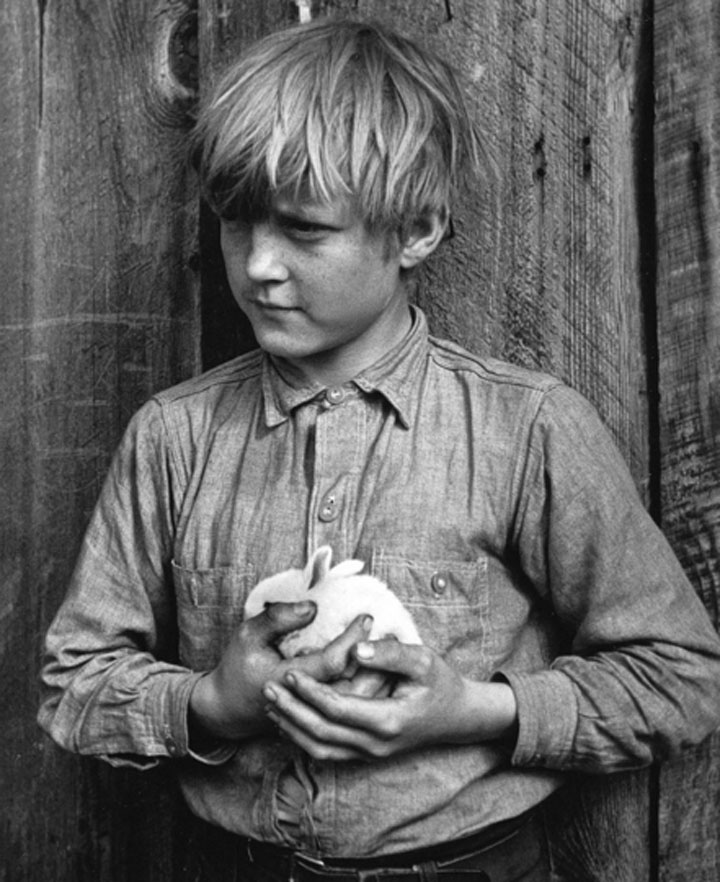

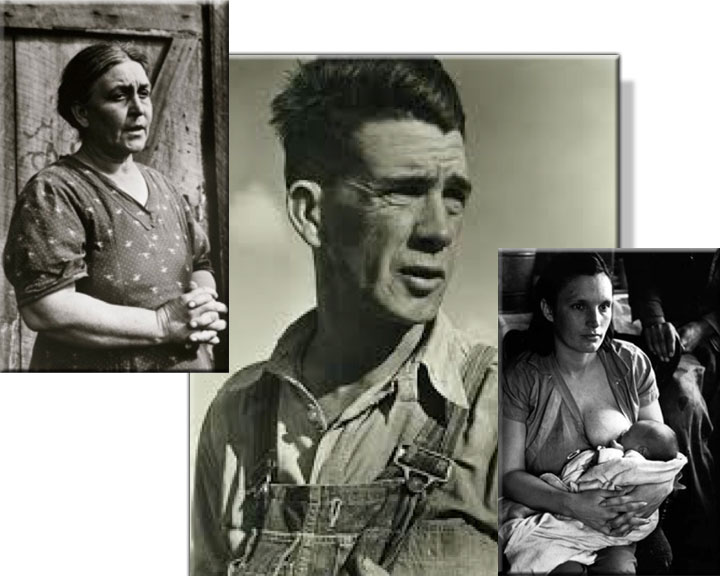

The pictures Bristol took on his travels with Steinbeck became famous anyway, thanks to their publication—along with images by Lange—in the April 1939 issue of Fortune and the June issue of Life, popular magazines with wide readership. As a result, Bristol’s photographs were used by the director John Ford in casting and costuming Ford’s award-winning movie adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath, released in January 1940. A second Life magazine article followed a month later. It featured Bristol’s “Joads” (shown above and at the top of the page) and the movie’s characters (shown below), displayed side by side with the telling tag, “Speaking of Pictures. . . these by Life prove facts in ‘Grapes of Wrath.’” However reluctantly the editors recognized the truth of Steinbeck’s book, they never approved of its author.

Russell Lee, The Grapes of Wrath, and a Great Depression Photography Exhibition at the University of Oklahoma

Now to an unfamiliar twist in this oft-told tale, one that is explored by James Swensen in his forthcoming study for the University of Oklahoma Press. To capitalize on the success of John Steinbeck’s novel and John Ford’s film, Ron Stryker’s Historical Section began mounting Grapes of Wrath exhibitions of work by the agency’s various photographers—with text taken from the novel—showing the conditions in Oklahoma and other parts of America’s Southern Plains that precipitated the exodus of native farm families, the problems they faced on the road, and their plight once they reached California. In March 1940, an FSA exhibition of 48 works by Russell Lee, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, and Ben Shahn (although none by Horace Bristol) appeared in the University of Oklahoma’s Memorial Student Lounge, sponsored by the departments of Sociology and Anthropology.

Willard Z. Park, an Anthropology Department faculty member, was the person most responsible for bringing the exhibition to campus. Park—whose brief tenure at the University of Oklahoma lasted from 1938 to 1942—was also part of a faculty group that purchased four copies of The Grapes of Wrath for the university library to help meet demand for the book—more than 100 University of Oklahoma students were on the waiting list to check out John Steinbeck’s novel. Swensen notes that in the wake of the campus exhibit “several [University of Oklahoma] students made trips to a local migrant colony in Norman, called ‘Tower Town,’ to see the plight of the migrants themselves.” Tower Town was located near 804 East Symmes Street, just east of Porter Avenue.

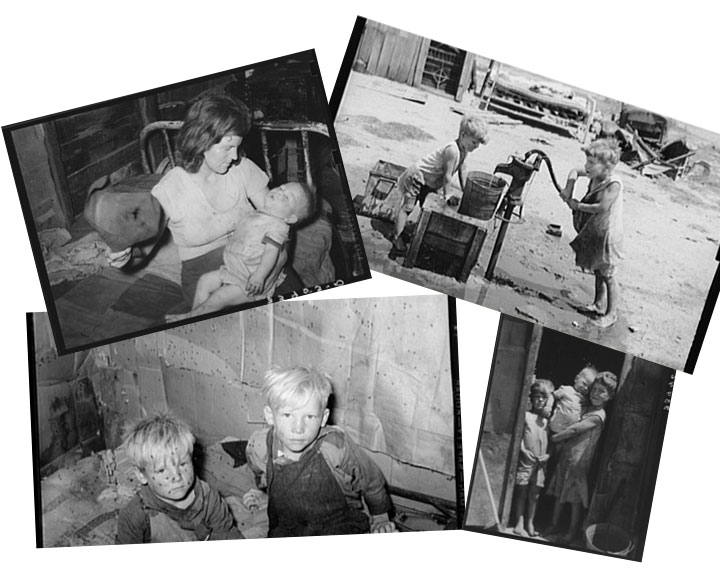

As poor as living conditions were for some Norman residents, Swensen explains that the FSA photographers who documented the plight of displaced Oklahomans during the latter years of the Great Depression traveled instead to the banks of the Canadian River in Oklahoma City, where more than 3,000 homeless Oklahomans had camped out. The University of Oklahoma Grapes of Wrath exhibition featured photographs of the Oklahoma City camps made by Russell Lee in 1939. Four examples of Lee’s harrowing images are shown above. They bear visual witness to Henry Hill Collins’ description of Oklahoma poverty in his 1941 book America’s Own Refugees: Our 400,000 Homeless Migrants (Princeton University Press):

Many of the inhabitants of this camp, a rent-free shack-town fashioned over and out of a former dump, were drought and tractor refugees from farms elsewhere in the State. . . . The ‘Housing’ . . . was almost entirely pieced together out of junk-yard materials by the unfortunates . . . . Neither camp provided sanitary facilities; children, looking like savages, played in the dumps, wandered along the neighboring, muddy banks of the half-stagnant Canadian River. . . . [S]o foul were these human habitations and so vast their extent that some authorities reluctantly expressed the belief that Oklahoma City contained the largest and worst congregation of migrant hovels between the Mississippi River and the Sierras.

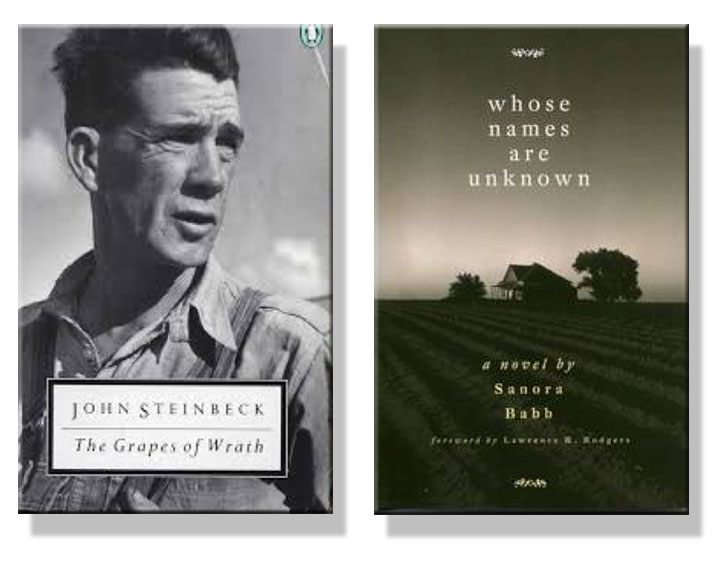

Whose Names are Unknown: Oklahoma’s Forgotten Novel

Our next story concerns a Great Depression novel written at the time of The Grapes of Wrath that remained unpublished until 2004. Its author was the remarkable Oklahoma native Sanora Babb. Born in the Territory’s Otoe Indian community in April 1907, seven months before Oklahoma became a state, Babb was living in California in 1938 and working for the Farm Security Administration. A contemporary of John Steinbeck, she actually met the author twice. She also kept detailed notes on what she observed in the California camps, copies of which were loaned by her boss Tom Collins—the man to whom Steinbeck dedicated The Grapes of Wrath—along with the meticulous reports Collins wrote about Oklahoma migrant culture and dialect.

John Steinbeck used Collins’ anecdotes and statistics to research The Grapes of Wrath. Sanora Babb used the stories she gathered to write her own novel, Whose Names are Unknown. Its title and subject attracted the attention of Bennett Cerf, the editor at Random House, who wanted to publish her book. Cerf abandoned his plans when The Grapes of Wrath became an overnight bestseller, another collateral casualty of John Steinbeck’s phenomenal success. When Babb approached Pascal Covici, Steinbeck’s loyal editor at Viking, he also declined.

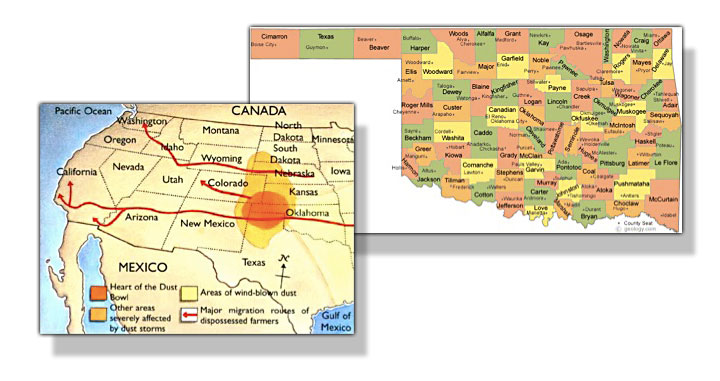

As a result, Whose Names are Unknown was unread for 65 years years before being published by the University of Oklahoma Press. But Babb’s book stands on its own feet as a classic of Great Depression fiction with significant differences from Steinbeck. While The Grapes of Wrath deals with migrants from far east-central Oklahoma—Sallisaw, in Sequoyah County, which was affected by drought and decline but wasn’t a Dust Bowl environmental disaster—Babb’s novel is set in Cimarron, the state’s westernmost county, roughly 450 miles from Sallisaw and squarely within the area of America’s Dust Bowl devastation. Unlike the author of The Grapes of Wrath, Babb was an Oklahoma native who experienced extreme poverty as a child and knew her people and their land firsthand.

Whose Names are Unknown was unread for 65 years before being published by the University of Oklahoma Press.

Babb had moved to California in 1929 to take a job at the Los Angeles Times. When she arrived the stock market had crashed, the Great Depression had begun, and the promised job dried up. A migrant without a home, she slept in a city park before leaving for Oklahoma in the mid-1930s, where she witnessed the terrible poverty gripping her native state. Eventually she returned to California to work for the FSA, serving migrant families stranded without a home or a job, just as she had been years earlier. In contrast, John Steinbeck gained much of his understanding of Great Depression conditions in Oklahoma second hand, through reading reports by federal aid workers like Babb and Collins and from his experience delivering food and aid to California migrants from the Southern Plains.

Still, the John Steinbeck-Sanora Babb story sounds like a classic smash-and-grab: celebrated California author steals the material of unknown Oklahoma writer, resulting in his financial success and her failure to get her work published. Ken Burns’ 2012 documentary The Dust Bowl touches on the subject, devoting space to Babb’s life and book in The Grapes of Wrath’s giant shadow. But Steinbeck absorbed field information from many sources, primarily Tom Collins and Eric H. Thomsen, regional director of the federal migrant camp program in California, who accompanied Steinbeck on missions of mercy.

As noted, John Steinbeck acknowledged Collins’ importance in his research for The Grapes of Wrath, although his promise to write an introduction and help Collins’ get his reports published failed—not unlike John Steinbeck’s book project with Horace Bristol. If Steinbeck read Babb’s extensive notes as carefully as he did the reports of Collins, he would certainly have found them useful. His interaction with Collins and Thomsen—and their influence on the writing of The Grapes of Wrath—is documented because Steinbeck acknowledged both. Sanora Babb went unmentioned.

Whose Names are Unknown was published by the University of Oklahoma Press shortly before Babb (shown above hanging wash with Tom Collins, standing beside an identified labor organizer and girl, and sitting with a group of migrants) passed away at 98. Like The Grapes of Wrath, Babb’s novel is must-reading for serious students of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression in Oklahoma. Its primary characters are Julia and Milt Dunne, an Oklahoma couple with two daughters—Lonnie and Myra—who are caught outside with their pregnant mother when a sudden storm blows up and Julia takes a fall. As a result, Julia’s third child is still-born, like Rose of Sharon’s infant in The Grapes of Wrath, and Milt buries the baby in the yard. Rose of Sharon’s abandonment by her husband in Steinbeck’s story is physical. Julia’s growing distance from Milt Babb’s narrative is psychological:

Sometimes Julia thought of the little boy who was so nearly born, saying in her mind it was better that he was dead, but in spite of this reasonable comfort, she felt the monotonous ache of grief and of Milt’s frustration. That peculiar ripening joy she had felt—with the child filling her and moving strongly with his secret life—had left her. The emptiness of her womb crept into her emotions, and she went through the days and nights feeling numb and alone. Milt was morose and easily angered, and although he spoke of the boy only once or twice, she felt coming from him some undetermined blame toward her.

Parallel Migrations: The Southern and the Northern Plains

Unlike our focus on two novels and two photographers in exploring the background of The Grapes of Wrath, our view of their Great Depression context requires a wide-angle perspective on the contrasting demographics of migration patterns from the Great Plains to the promised lands of the American West in the 1930s. I say promised lands because migration to California from Oklahoma and other Southern Plains states wasn’t the only instance of mass westward movement during the decade recorded in John Steinbeck and Sanora Babb’s writing and the photographs made by Horace Bristol and Russell Lee.

James Gregory, the preeminent historian of the migration of Southwesterners to California during the Great Depression, places the total figure for out-migration to the Golden State in the 1930s from the Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas at 315,000-400,000. (California received about a million American migrants during the decade, and they came from all over America, not just the Southern Plains.) Notably, fewer than 16,000 of these Great Depression refugees—less than six percent of the total number of migrants from the four states mentioned who ended up in California—came from the area of the Dust Bowl. Gregory notes that journalists of the period are primarily to blame for “confusing drought with dust” and oversimplifying the facts: “the press created the dramatic but misleading association between the Dust Bowl and the Southwestern migration.” The subtitle of Gregory’s excellent book—American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (Oxford University Press, 1991)—makes this critical point.

Migration to California from Oklahoma and other Southern Plains states wasn’t the only instance of mass westward movement during the decade recorded in John Steinbeck and Sanora Babb’s writing and the photographs made by Horace Bristol and Russell Lee.

So it isn’t surprising that the role played by Oklahoma and its residents looms so large in the public memory of the Southern Plains migration to California during the Great Depression. The Federal Writers Project’s publication Oklahoma: A Guide to the Sooner State (1941) reported that half of the state’s population was on relief by the late 1930s. In his remarkable 1942 study, Ill Fares the Land: Migrants and Migratory Labor in the United States, California’s progressive journalist Carey McWilliams stated that by 1935, “61.2 per cent of farms in Oklahoma were operated by tenants” and between 1935 and 1940 Oklahoma lost a total of 32,000 farms or more at a rate of 18 per day. Moreover, McWilliams noted, from July 1, 1935 to June 30, 1939, almost 71,000 Oklahomans crossed the Arizona border into California. Interestingly, the bulk of this exodus came from Oklahoma’s populous central counties; the four counties with the highest number of outbound migrants were Oklahoma, Caddo, Muskogee, and Tulsa.

As Oklahomans, Californians, and readers of The Grapes of Wrath quickly learned, the term “Okie” became a derisive identifier for all migrants to California, not only from Oklahoma but from other Southwestern states as well. “Little Oklahoma” was the local name for the Alisal, the area east of John Steinbeck’s hometown of Salinas where white migrants from the Plains states were clustered, out of sight and out of mind of respectable Salinians—as Steinbeck noted in his letters and in L’Affaire Lettuceberg, the angry satire he wrote (and destroyed) before beginning The Grapes of Wrath.

‘Okie’ became a derisive identifier for all migrants to California, not only from Oklahoma but from other Southwestern states as well.

Even today, it is hard to avoid perpetuating the “Okie” and “Dust Bowl” stereotypes and the oversimplifications that they represent. These became so pervasive that historians of the Great Depression have paid little attention to a parallel migration of similar size—approximately 300,000 individuals—from the Northern Plains states of Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota to the Pacific Northwest states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. One historian, Rolland Dewing, has helped correct the record, explaining that Northern Plains migrants left their home states because of drought conditions and economic collapse, much like their counterparts to the south. In Regions in Transition: The Northern Great Plains and the Pacific Northwest in the Great Depression (University Press of America, 2006), Dewing notes that approximately two-fifths came from North Dakota, two-fifths from South Dakota, and one-fifth from Nebraska.

Steinbeck’s Oklahomans and America’s “Other Migrants”

But as massive in scale as the migration from the Northern Plains to the Pacific Northwest became during the Great Depression, the particulars of this phenomenon have for a variety of reasons remained largely forgotten. As Rolland Dewing explains in his book, there was no agribusiness equivalent to California’s Central and Imperial valleys in the Pacific Northwest—no foundation for the systematic economic exploitation and mistreatment of the newcomers.

The Northwest timber industry was doing quite well as the Northern Plains economy collapsed, and this stability—along with other positive economic factors in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho—helped ease the transition of Northern Plains migrants, which peaked in 1936, when the economy of the host region was picking up. Because the population of the Pacific Northwest was aging at the time of the Great Depression, younger migrants were welcomed by many as a demographic addition, unlike those arriving in California from Oklahoma and other Southern Plains states, like the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath.

Because the population of the Pacific Northwest was aging at the time of the Great Depression, younger migrants were welcomed by many as a demographic addition, unlike those arriving in California from Oklahoma and other Southern Plains states, like the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath.

Then, too, the socioeconomic and educational levels of Northern Plains migrants were closer to those of the Pacific Northwest states, so newcomers and hosts shared more in common than Southern Plains migrants did with less friendly Anglo-Californians. Indeed, many residents of the Pacific Northwest had been born or maintained family roots in the upper-Midwest: Northern Plains migrants seemed more alike than different in background and behavior to their hosts.

Like Steinbeck’s migrants in The Grapes of Wrath, Northern Plains residents suffered terribly during the Great Depression. South Dakota, for example, experienced a seven percent population decline in the 1930s. The population loss for Oklahoma was much less: the state’s population was 2,396,040 in 1930 and 2,336,434 in 1940 (a 2.5 percent decline). But migrants from the Northern Plains to the Pacific Northwest never experienced suffering on the scale of their southern counterparts who migrated to California. No one wrote a Grapes of Wrath about them. As a consequence their stories have been largely forgotten.

Rescuing Sanora Babb from John Steinbeck’s Shadow

Horace Bristol and Russell Lee were among the most important documentary photographers of Great Depression America. Like the pictures of migrant mother and children made by Dorothea Lange, their images helped sear the truth behind The Grapes of Wrath into America’s collective consciousness. The photographs Bristol took on assignment with Steinbeck for Life proved essential to the casting and costuming of the Joads in the movie version of the novel. But if The Grapes of Wrath hadn’t been so successful, Sanora Babb’s novel of Oklahoma would probably have been published as promised and might have become a Great Depression classic being celebrated, like The Grapes of Wrath, on its 75th anniversary.

Finally, if Steinbeck’s timeless prose—along with photographs by Bristol, Lee, and Lange and John Ford’s movie—hadn’t evoked the Southern Plains exodus to California so powerfully for Americans living through the Great Depression, our memory of migration in the 1930s might include the parallel movement of Northern Plains refugees to the Pacific Northwest. But the migration of these displaced Americans wasn’t chronicled by a John Steinbeck or a Sanora Babb: their suffering was on a smaller scale and they encountered less hostility. Thus art copies history but also reflects it. New light on Great Depression migration and the forgotten background of The Grapes of Wrath from the University of Oklahoma further illuminates Steinbeck’s masterpiece. It also helps rescue a forgotten work, written by a native Oklahoman, from the shadow of a greater writer.

SteinbeckNow.com is proud to publish David Wrobel’s feature as the 80th post produced by our website in its first eight months. A scholar of United States history, David is also an avid reader and deep thinker on the writing of John Steinbeck. He contributed a chapter about Steinbeck’s social-protest fiction to Regionalists on the Left, an anthology of essays edited by Michael C. Steiner, and he gave a lecture, John Steinbeck’s America: A Cultural History of the Great Depression and World War II, to a large audience at the University of Oklahoma’s 2013 Teach-In on the Great Depression and World War II. He is currently working on “John Steinbeck’s America: A Cultural History, 1930-1968.”

John Steinbeck’s Powerful Ambivalence: Book Review

John Steinbeck remained a force in American cultural life for three decades after his so-called years of greatness between 1936 and 1939—a remarkably productive period marked by the publication of In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), The Long Valley (1938), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). On the 75th anniversary of Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, the reasons for its continuing popularity—despite the dismissive evaluations of critics—are worthy of reconsideration.

John Steinbeck remained a force in American cultural life for three decades after his so-called years of greatness between 1936 and 1939—a remarkably productive period marked by the publication of In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), The Long Valley (1938), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). On the 75th anniversary of Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, the reasons for its continuing popularity—despite the dismissive evaluations of critics—are worthy of reconsideration.

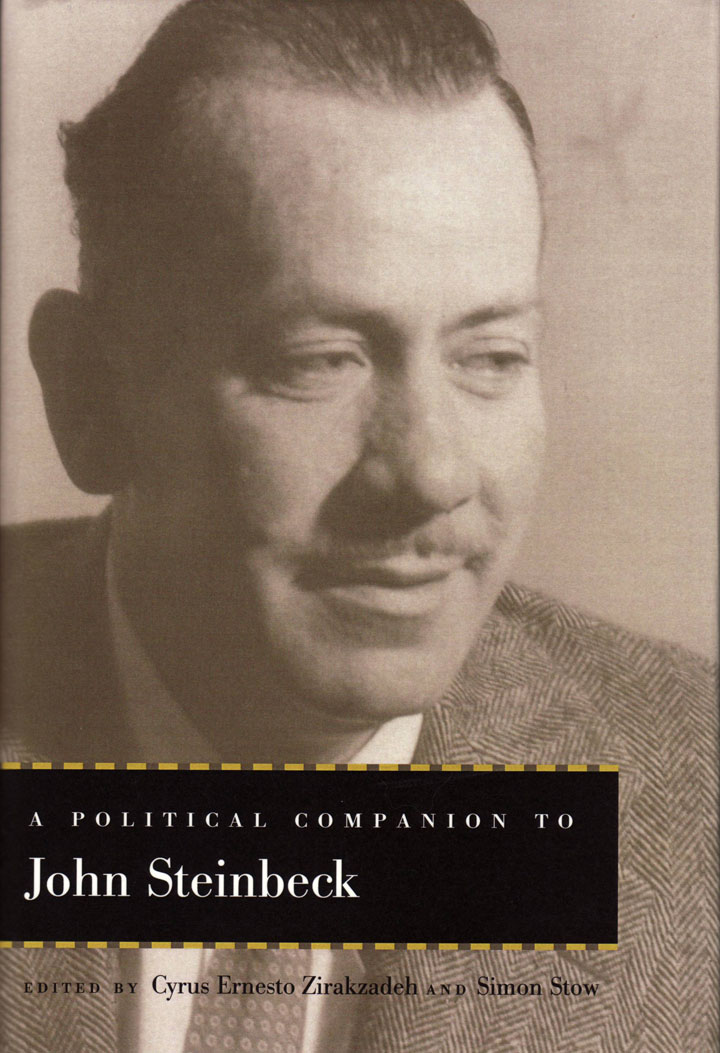

‘Critics do not like to be confounded in their attempts to compartmentalize,’ Simon Stowe reminds us in ‘The Dangerous Ambivalence of John Steinbeck,’ his introduction to A Political Companion to John Steinbeck.

“Critics do not like to be confounded in their attempts to compartmentalize,” Simon Stowe reminds us in “The Dangerous Ambivalence of John Steinbeck,” his introduction to A Political Companion to John Steinbeck (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2013), co-edited with Ernesto Zirakzadeh. Stowe shows how Steinbeck’s ambivalence about America, government, community, and individualism confounds Steinbeck’s critics and helps explain the disconnect between Steinbeck’s readers and many academics. Other contributors illuminate other areas of interest with equal vigor.

From The Grapes of Wrath to World War II and Beyond

During World War II, John Steinbeck was subjected to federal background investigations, even as he worked to advance the nation’s cause, writing the much-maligned yet influential novel and play The Moon Is Down (1942)—not explicitly, yet quite obviously about the Nazi invasion of Norway—and Bombs Away (1942, the positive account of a U.S. Air Force bomber team. He traveled to England in June of 1943, then on to North Africa, Sicily, and the Italian mainland to report on the war on the ground for the New York Herald Tribune. He also wrote a pair of works set in Mexico—The Forgotten Village (1941) and The Pearl (1947)—that addressed the ethical complications surrounding the intersections of modern medicine and indigenous folk cultures, followed by Cannery Row (1945), a divergent work that might be considered the first novel of the coming American counterculture.

Cannery Row . . . might be considered the first novel of the coming American counterculture.

While less productive in the 1950s, Steinbeck completed one of his most successful and enduring novels, East of Eden (1952), reflecting the generational conflicts that came to mark the post-war period, as well as Sweet Thursday (1954), the critically undervalued sequel to Cannery Row. In addition, the 1950s saw the publication of John Steinbeck’s screenplay for Elia Kazan’s acclaimed film Viva Zapata! (1952) and Once There Was a War, the writer’s collected World War II dispatches (1958).

In 1966, John Steinbeck reaffirmed his deep attachment to his country in his last book, America and the Americans.

John Steinbeck began the 1960s with what would be his last novel, The Winter of Our Discontent (1961), followed by his endearing and enduring narrative Travels with Charley (1962)—an attempt to reconcile his growing sense of alienation from his culture—and the Nobel Prize for Literature, awarded in 1962 over the lamentable protestations of his critics. In 1966, he reaffirmed his deep attachment to his country in his last book, America and the Americans, essays on various aspects of national life and character. In 1966-67 he toured Vietnam, where one of his sons was serving in the U.S. Army. As in World War II, the newspaper dispatches he sent home supported his country and its policies, although he later changed his position regarding his friend Lyndon Johnson’s increasingly unpopular war in Southeast Asia.

Steinbeck and Politics from Great Depression to Cold War

In short, John Steinbeck’s writing of four decades serves as a remarkable guide through the controversies and complications that characterized American politics and culture in the middle third of the 20th century. If it is appropriate to consider the nation in the middle third of the 19th century under the rubric of Walt Whitman’s America, as David Reynolds’ 1995 book of the name has done, and to label the last third of that century Mark Twain’s America as Bernard DeVoto did in his earlier book, then it seems no less reasonable to view the years from the Great Depression to the Great Society through the lens of John Steinbeck’s acute vision, as Cyrus Ernesto Zirakzadeh and Simon Stow do in A Political Companion to John Steinbeck. A strong addition to the excellent series of volumes called Political Companions to Great American Authors—one that includes Henry Adams, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson—the anthology attempts a fuller consideration of Steinbeck’s centrality to at least the first part of American life and politics in the mid-20th century.

John Steinbeck’s writing of four decades serves as a remarkable guide through the controversies and complications that characterized American politics and culture in the middle third of the 20th century.

Not surprisingly, Steinbeck’s work in the 1930s and 1940s gets most of the attention of the book’s many contributors. This includes co-editor Zirakzadeh’s provocative discussion of Steinbeck as a “revolutionary conservative or a conservative revolutionary”; Donna Kornhaber’s treatment of politics and Steinbeck’s playwriting; Adrienne Akins Warfeld’s examination of Steinbeck’s Mexican works from the 1940s; Charles Williams’ insightful exploration of Steinbeck’s “group man” theory in In Dubious Battle; the volume’s standout essay by James Swensen on Dorothea Lange’s photographs and the work of the John Steinbeck Committee to Aid Agricultural Organization; Zirakzadeh’s treatment of The Grapes of Wrath as novel, film, and inspiration for the music of Bruce Springsteen; and Mimi R. Gladstein and James H. Meredith’s “Patriotic Ironies,” an account of John Steinbeck’s wartime service. Other essays examine Steinbeck’s legacy in the songs of Springsteen, Travels with Charley and America and Americans (together), and The Winter of Our Discontent.

John Steinbeck’s Enduring Relevance, Despite the Critics

In addition to the absence of any extended treatment of Cannery Row, the second half of Steinbeck’s career in general gets short shrift. There is no significant coverage of East of Eden, nor of Steinbeck’s powerful defense of the playwright Arthur Miller in 1957 against the charges of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the political context of Cold War paranoia in which HUAC operated. Partisan politics are also largely absent from the essays, although as evident from his correspondence John Steinbeck held strong political opinions, beginning in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s. Steinbeck’s dispatches from the Vietnam War (recently republished by the University of Virginia Press) are ignored, and greater attention to the 1950s and 1960s would have made the anthology more complete. With notable exceptions, senior Steinbeck scholars such as Robert DeMott and Susan Shillinglaw are absent from the roster of contributors: Kevin Hearle’s deep perspective on the politics of race and place would have augmented the volume but is missing.

John Steinbeck held strong political opinions, beginning in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s.

Despite the gaps, however, A Political Companion to John Steinbeck achieves the goal of its editors and contributors to illuminate the complexities of John Steinbeck’s political thought and underscore the enduring contribution of his work to American political thought. Well-edited and integrated, the essays explore nuances and complications of Steinbeck’s personal political thought while providing an effective response to the generations of critics who have found his work excessively heroic, sentimental, moralistic, or didactic—or too popular to be taken seriously. Whatever the tensions in John Steinbeck’s writing at a particular moment—between group man and the individual, traditionalism and liberalism, communism and capitalism, alienation from and affirmation of America—contradictions and ambiguities are distinctive characteristics of his art and ambivalence frequently defines his thinking. These traits help account for his continuing relevance.

Whatever the tensions in John Steinbeck’s writing at a particular moment . . . contradictions and ambiguities are distinctive characteristics of his art and ambivalence frequently defines his thinking. These traits help account for his continuing relevance.

John Steinbeck may not be honored everywhere in the academy 75 years after The Grapes of Wrath, but he remains popular with readers worldwide. His dedication to the advancement of human welfare and the nurturing of human relations through art may seem too low-brow to arbiters of the current literary canon, and political extremists on both right and left continue to attack his work, from In Dubious Battle to The Grapes of Wrath and beyond. But a significant segment of the reading public still feels deeply connected to his fiction. More than any other writer of his day, Steinbeck captured and conveyed the striving of average Americans during the Great Depression, World War II, and two subsequent wars—one cold, the other hot. By placing Steinbeck’s powerful, productive ambivalence center stage, A Political Companion to John Steinbeck nudges us toward a fuller appreciation of the writer and his work in a year in which we celebrate The Grapes of Wrath, his masterpiece.

A different version of this review appeared in The b2 Review.