John Steinbeck’s split-screen picture of women—Mother Virgin vs. Vestibule Whore—continues to trouble contemporary readers of East of Eden and his Cannery Row fiction. Male characters like Doc, Lee, and Sam Hamilton are complex . . . intelligent men, like Steinbeck, with mixed moral motives. Dora, Suzy, and Cathy, all prostitutes of one type or another, also show a range of feeling and behavior, but far narrower. Steinbeck’s depiction of whores almost seems bipoloar, flat and forced and, the case of Cathy, not completely convincing. Was Steinbeck, with the shining exception of Ma Joad, a male chauvinist whose writing failed to understand or value women equally with men? Reading East of Eden and Steinbeck’s Cannery Row novels in the context of Steinbeck’s contempt for conventional morality suggests that he was far from it.

Was Steinbeck, with the shining exception of Ma Joad, a male chauvinist whose writing failed to understand or value women equally with men?

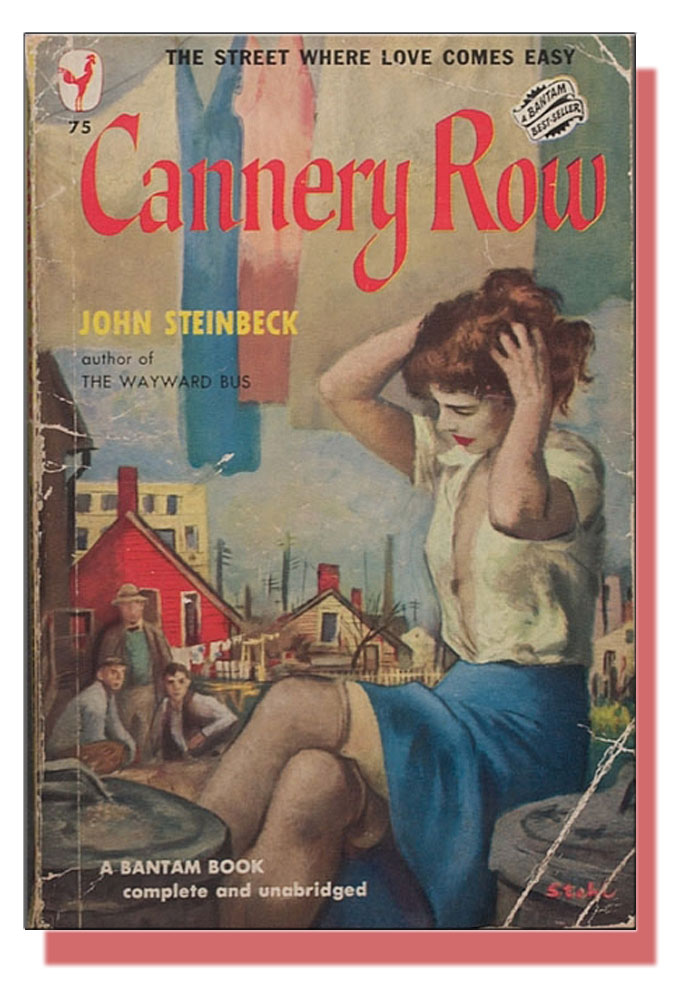

John Steinbeck was, in fact, atypical of his gender and time in reversing the status of “churchy” mother-wives and the “ladies of the night” with hearts of gold who were their moral superior from Steinbeck’s point of view. In Steinbeck’s Cannery Row books, “nice women” are gossipy, negative Nancies living lives of hypocrisy, while the “working girls” offering sexual services to husbands and single men are positive, contributing members of society who display compassion and honesty without shame. Cathy, the sociopathic madam in East of Eden, is the exception who proves the rule.

In Steinbeck’s Cannery Row books, ‘nice women’ are gossipy, negative Nancies living lives of hypocrisy, while the ‘working girls’ offering sexual services to husbands and single men are positive.

But this begs a nagging question: Is it sexist to sort women into dramatically opposed categories of character, behavior, and moral worth, however heavily weighed in favor of whores? From a feminist point of view, probably so. In the context of Steinbeck’s age, however, the writer’s inversion of current values was both radical and, by today’s standards, agreeably accepting. Depicting prostitutes as positive role models was intended to shock Steinbeck’s readers, and did. But even from the perspective of modern feminism, his portrayal of their status was ahead of its time. Steinbeck’s Cannery Row whores and East of Eden prostitutes were, exceptions noted, more financially secure and less dependent on men than the wives and mothers whose husbands and son used their services.

In the context of Steinbeck’s age, his inversion of current values was both radical and, by today’s standards, agreeably accepting. Even from the perspective of modern feminism, his portrayal of women’s status was ahead of its time.

Steinbeck’s upside-down vision was no doubt rooted in his upbringing by a repressed, retiring father and a strong-minded mother with social ambitions in a small frontier town. To his way of thinking, the moral framework and sentiments about sex he learned at home and in Sunday School lacked logic and, worse, justification in the natural scheme of things. To Steinbeck, the worst aspect of Salinas culture was its hypocrisy, especially with regard to sex, but also money. Salinas hypocrites of both kinds (often the same people) populate his fiction, particularly East of Eden, one reason the novel still feels so fresh to contemporary readers.

To his way of thinking, the moral framework and sentiments about sex he learned at home and in Sunday School lacked logic and, worse, justification in the natural scheme of things.

The inspiration for Steinbeck’s characters wasn’t limited to Salinas. His Cannery Row prostitutes—notably Dora, the madam with a heart of gold—were based on real-life figures from nearby Monterey, a place he much preferred to the town where he grew up. In Sweet Thursday, a Christian Science official arrives on Cannery Row to check on a group of female Christian Science followers who, to his dismay, he learns are working for Dora, the heart-of-gold madam of a popular brothel. The idea for this over-the-top incident originated in Steinbeck’s experience, decades earlier, as a struggling writer in New York City. During his time there he dated a chorus girl and met her chorine friends, many of whom belonged to a large Christian Science church, probably the one led in the 1920s by a charismatic female Christian Science practitioner with a prosperous following.

A Christian Science official arrives on Cannery Row to check on a group of female Christian Science followers who, to his dismay, he learns are working for Dora, the heart-of-gold madam of a popular brothel.

But what of Cathy, the murderous madam in East of Eden? Christian Science was farthest thing from her deeply disturbed mind. Steinbeck biographers have suggested that Cathy’s inspiration was Steinbeck’s second wife, though that’s less important to this discussion than the profile Steinbeck creates of a heartless character—irrespective of gender—born bad. Cathy isn’t condemned because she’s a whore who refuses to remain with her husband and babies. Clearly, she was never the parenting type (nor, for that matter, was John Steinbeck). Her sin isn’t whoring; it’s monstrous, premeditated murder. Exploiting the affections of the kindhearted madam who takes her in after she abandons her home, Cathy poisons her heart-of-gold host and takes over her business, running a notorious house where anything sexual goes . . . for a price. Blackmail is on her mind, too, and her desire to expose the town’s hypocritical citizens seems somehow justified and strangely satisfying, despite her dark motives.

But what of Cathy, the murderous madam in East of Eden? Christian Science was farthest thing from her deeply disturbed mind.

And yet . . . Despite Steinbeck’s ironic moral inversion of virgin and whore, can the prostitutes who populate his fiction still be seen as stereotypes? The answer has to be a qualified yes, and it tends to blunt the impact of Steinbeck’s blow against hypocrisy for readers today. Yet he took his small town “working girls” seriously, and they got him into trouble, even among certain sophisticates in his high-flying circle of New York colleagues and collaborators. Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, the musical team that based the Broadway musical Pipe Dream on the Cannery Row characters from Sweet Thursday, turned Steinbeck’s heart-of-gold heroine Suzy, who worked at Dora’s and fell in love with Doc, into what Steinbeck bitterly described as a less-than-believable “visiting nurse.”

Steinbeck took his small town ‘working girls’ seriously, and they got him into trouble, even among sophisticates in his high-flying circle of New York colleagues and collaborators.

Because he was serious, I prefer to give John Steinbeck the benefit of the doubt on the subject of prostitutes. It’s important to remember that his “whore with a heart of gold” characters like Dora and Suzy are a literary trope with a moral purpose, social stereotypes notwithstanding. In Cannery Row, Sweet Thursday, and (Cathy excepted) East of Eden, they represent a courageous reversal of conventional values that no doubt would have offended Steinbeck’s mother, had she lived, while probably pleasing his father, who died shortly before Steinbeck’s first book success. That was in the 1930s, back in small town Salinas. But did sophisticated New York in the 1950s react that differently? Even Rodgers and Hammerstein, the kings of Broadway musical theater, choked on Steinbeck’s whores when they staged Cannery Row and failed, or so Steinbeck felt, as a result.