A summary of recent books by Russell Brand and Naomi Klein about current events, global conflict, and corporate accountability associated their views with John Steinbeck and William Blake, the English poet and artist admired by John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. But how accurate is it to compare literary artists like Blake and Steinbeck with activists like Naomi Klein or Russell Brand, cultural critics whose appeal is topical and in the moment? It’s true that all four writers oppose oppression and speak truth to power in their work. But the similarity ends there, and the earlier discussion ignored another English poet: John Milton, a writer who has more in common with John Steinbeck and William Blake than Russell Brand or Naomi Klein.

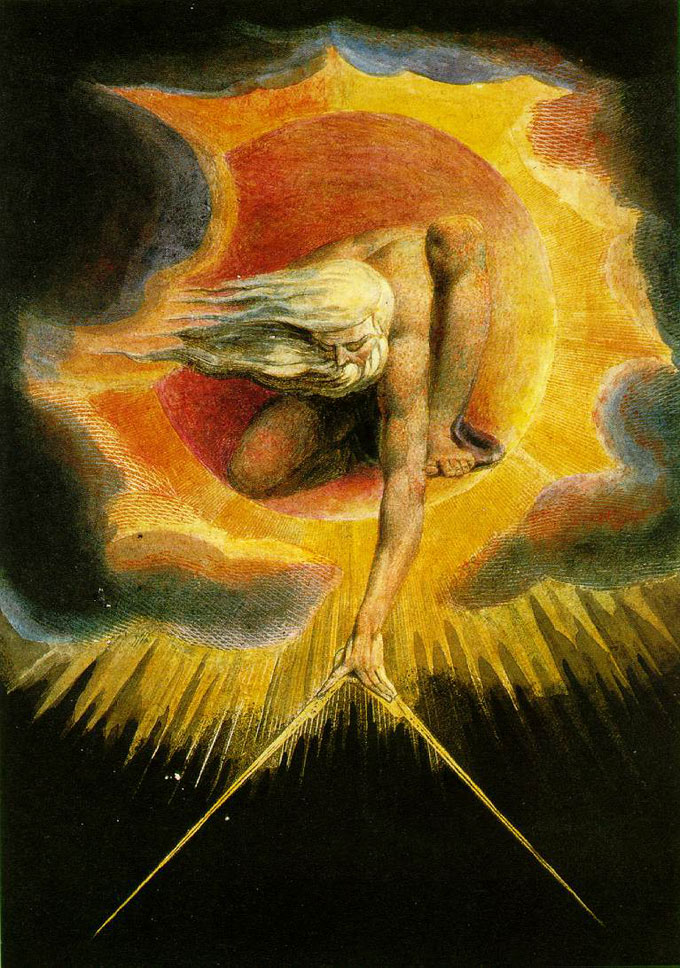

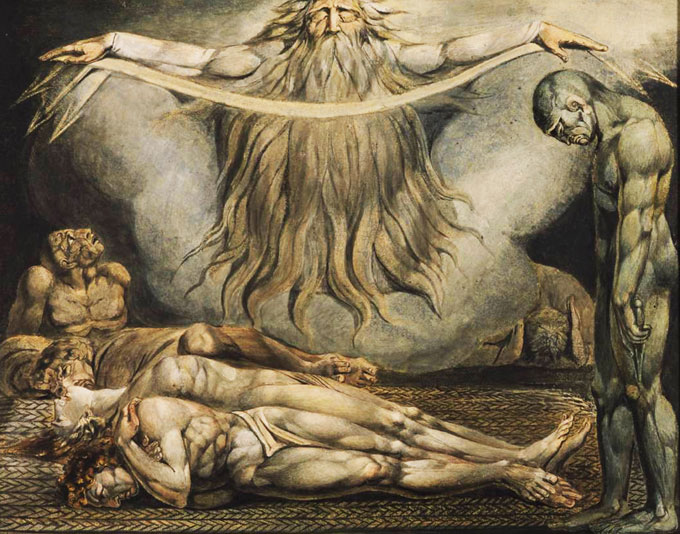

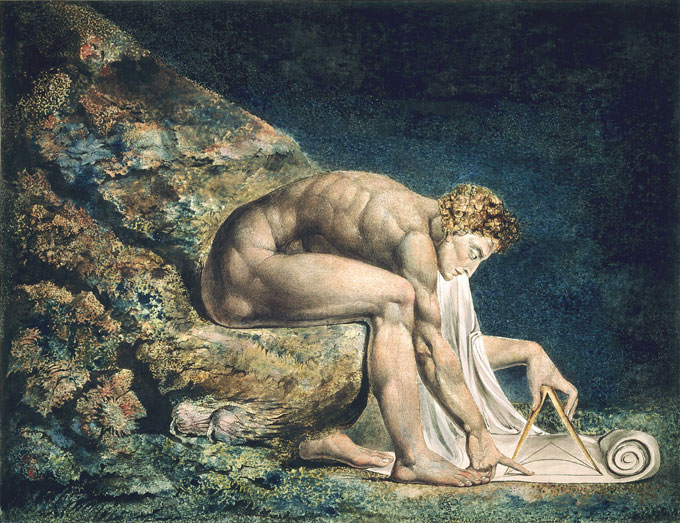

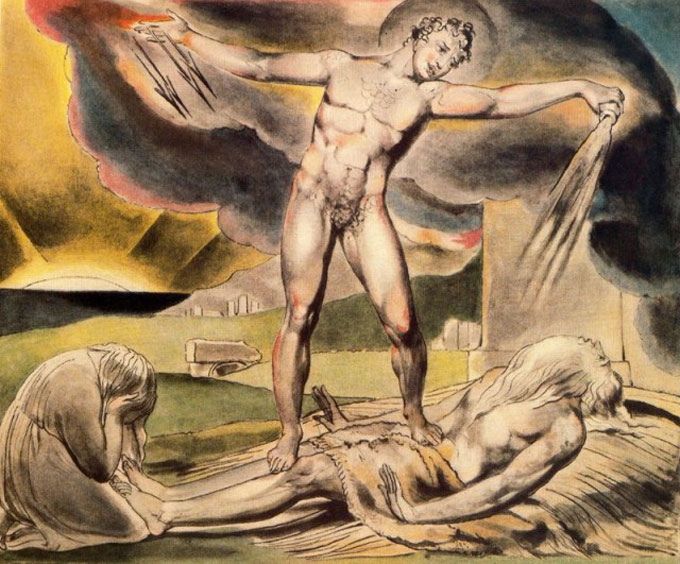

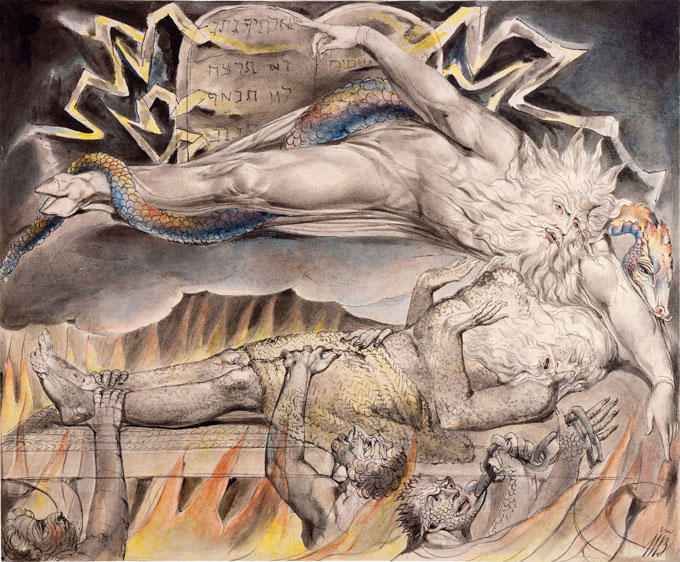

William Blake’s dramatic etched and painted images—drawn from the Bible, world mythology, and Blake’s imagination—have been speaking powerfully since he died in poverty in 1830 and are sampled here for readers unfamiliar with his extraordinary art. His reach is cosmic, and the significance of his work is symbolic, not local or literal like modern writers. Likewise, John Steinbeck’s fiction, even at its most realistic, transcended the time and place in which it was set and tells a universal story applicable to every age. I consider both Blake and Steinbeck to be prophetic poets, like John Milton, who explored the human spirit and who will be read for years to come. Klein is an accomplished journalist and Brand’s jeremiads are often amusing, but neither achieves the depth or breadth to justify comparison with John Steinbeck or William Blake. The Bible and John Milton tell me so.

John Steinbeck, William Blake, and the Politics of Poetry

Blake and Steinbeck championed the downtrodden and called out the kings and corporations responsible, in their view, for pervasive poverty, inequality, and political corruption when they were alive. The context of Blake’s writing included the three great revolutions of his time—the political revolutions in America and France, which he praised, and the industrial revolution in England that created the “dark Satanic mills” he decried. Volumes have been written about the political origins and implications of Blake’s work within the framework of the English Romantic movement of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, and Byron. Like Byron and sometimes Shelley, Blake was a rebel with a cause. But Blake was also a religious visionary, and the Bible inspired his art, not political pamphlets, love affairs, or misadventures in foreign lands.

Wordsworth started in the same radical vein, supporting the French Revolution and opposing urbanization, commodification, and the industrial revolution’s displacement of England’s agricultural poor. If this sounds familiar, it’s because John Steinbeck tells a similar story in The Grapes of Wrath (a Biblical title with a Blakean ring). But Wordsworth became a conservative in old age, writing sonnets praising duty and domesticity that promoted comfort with the status quo. Likewise, John Steinbeck defended America’s intervention in Vietnam, causing various liberal friends and literary critics to view him as a turncoat against progressive principles. As with Wordsworth, Steinbeck’s late-life change damaged his reputation as a public figure. At a minimum it complicates matters when comparing him to William Blake, Naomi Klein, or Russell Brand—a passionate ranter whose first name should be Fire. Unlike Steinbeck, Klein, or Brand, Blake was involved in a lifelong project of deconstructing social theory into metaphysical truth, ridiculing parties and politicians until the day he died. Like Steinbeck, however, he distrusted polemics and rejected identification with any ideology.

Why do we continue to read William Blake and John Steinbeck with a shock of recognition at old truths made new? Because their politics of poetry transcends time and place and speaks to every age. (We’ll see whether Naomi Klein and Russell Brand have the same appeal for readers generations from now.) Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath portray the Biblical symbol of a barred Paradise following a human Fall, an ancient archetype that powerfully the expresses the human condition. Like William Blake, John Steinbeck discovered the origin of evil in the Snake within each of us: the self-divided consciousness that conflicts every person who is truly alive. Tip O’Neill, the former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, claimed that “all politics is local.” Russell Brand appears to agree, while Naomi Klein thinks global politics matter most. Neither point of view pierces the human heart where Blake and Steinbeck find the beginning of all conflict, global or local. Today we don’t read William Blake as counterpoint to John Stuart Mill, or John Steinbeck as ally or antidote to Karl Marx. Connecting Brand and Klein to Marx and Mill makes more sense than wishful thinking about “channeling” John Steinbeck.

Russell Brand, Naomi Klein, and the Ideology of Politics

But differences between the art of John Steinbeck and that of William Blake are worth noting. The Grapes of Wrath depicts the triumph of predatory capitalism over family farming as a fight between political interests with conflicting ideologies. While denying that he was an ideologue, Steinbeck supported the New Deal and (to his credit) took sides in the fight. Russell Brand and Noami Klein, on the other hand, don’t pretend to be above politics, interpreting current events as a clash of ideologies, not cultures or faiths. In an era of even bloodier revolution, William Blake saw every ideology as a form of mental tyranny, “mind-forg’d manacles” that tie down the soul and perpetuate the cycle of conflict among individuals, interest groups, and nations. It was the spirit, not the ideology, of revolution that engaged Blake’s imagination as a writer.

Blake believed that the work of the artist and poet is to help free individual consciousness from conceptual chains, like the prophet Ezekial in “A Memorable Fancy.” Blake’s reference to native cultures sounds very modern:

I then asked Ezekiel why he ate dung, and lay so long on his right and left side. He answer’d, ‘The desire of raising other men into a perception of the infinite: this the North American tribes practise, and is he honest who resists his genius or conscience only for the sake of present ease or gratification?’

John Steinbeck’s version of Blake’s Ezekial figure is the preacher Jim Casy in The Grapes of Wrath, a prophet who endures pain to “cleanse the doors of perception” and achieves salvation through self-denial, self-sacrifice, and self-transcendence. Jim Casy dies in Steinbeck’s story but, like Tom Joad, his holy ghost lives on. In Dubious Battle presents a similar pattern of questioning introspection and self-transcendence in the character of Doc, the doubting physician who sees beyond the conflicting ideologies of capitalism and communism to a cosmic vision worthy of William Blake: Group Man as godlike, a corrupted version of Blake’s “human form divine.” Ed Ricketts has been identified by scholars as the inspiration for each of these characters in John Steinbeck’s fiction; it’s worth noting that Ricketts deeply distrusted ideology and rejoiced in reading William Blake, one of a handful of ageless poets he identified as “breaking through” to higher vision and cosmic consciousness in their art.

John Steinbeck, William Blake, and their Poetic Prophets

Blake always called his poetic vision “prophetic.” Steinbeck presents both prophetic figures—In Dubious Battle’s physician Doc, The Grapes of Wrath’s preacher Casy—in the same mode of thought and speech. Each is a seer in two senses, like Blake’s Old Testament prophets: they see into the human soul and they see into the immediate future. Doc speaks of “the Blood of the Lamb.” Casy’s dialog becomes increasingly poetic as the novel progresses, as when he prays reluctantly over a woman dying on the exodus to the Promised Land of California. Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost must also be kept in mind to complete the picture. Blake and Steinbeck were intimately familiar with Milton’s great narrative of human fall from grace, innocence, and Paradise. Blake considered Satan the true hero of Milton’s poem because Satan, not God, represents energy, imagination, and “breaking through,” and Steinbeck was familiar with Blake’s radical reinterpretation of Milton’s moral message. It clearly colors Casy’s rejection of religion and helps us understand Doc’s prophecy about the ambiguous outcome of the “dubious battle” (a phrase borrowed from Paradise Lost) between the strikers and police.

Which brings us back to Russell Brand and Naomi Klein. Neither writer has John Milton, William Blake, or John Steinbeck’s grounding in the prophetic literature or language of the Bible, and the gap is apparent. As a result, reading either one feels a bit like skating on thin ice. Firebrand rhetoric (Brand) and statistical analysis (Klein) fail to convey the sense of depth and permanence about politics found in John Steinbeck, who has far more in common with William Blake and John Milton than with Russell Brand or Naomi Klein. It might be better to describe Steinbeck as channeling these writers than to assert that Klein or Brand has channeled John Steinbeck in books that, however relevant they seem today, are too busy taking the pulse of the body politic to get to the heart of the matter.