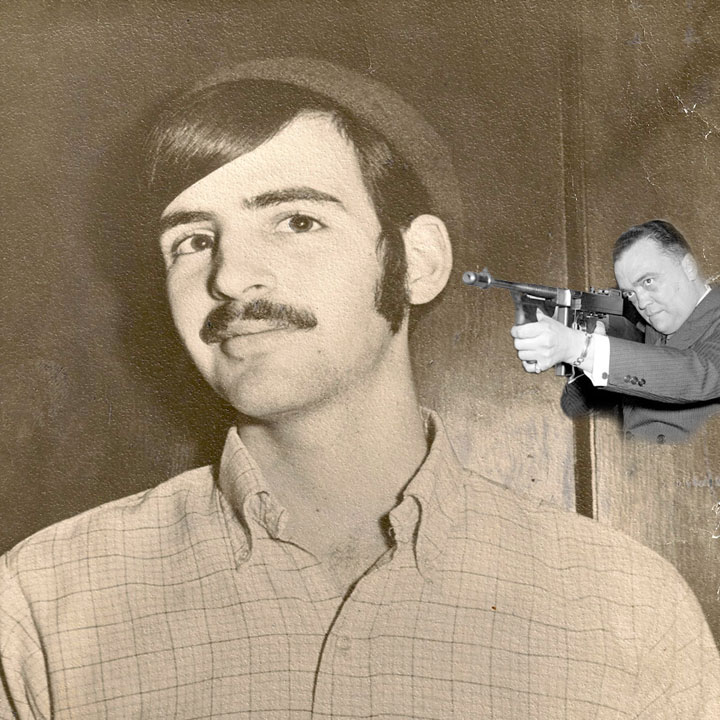

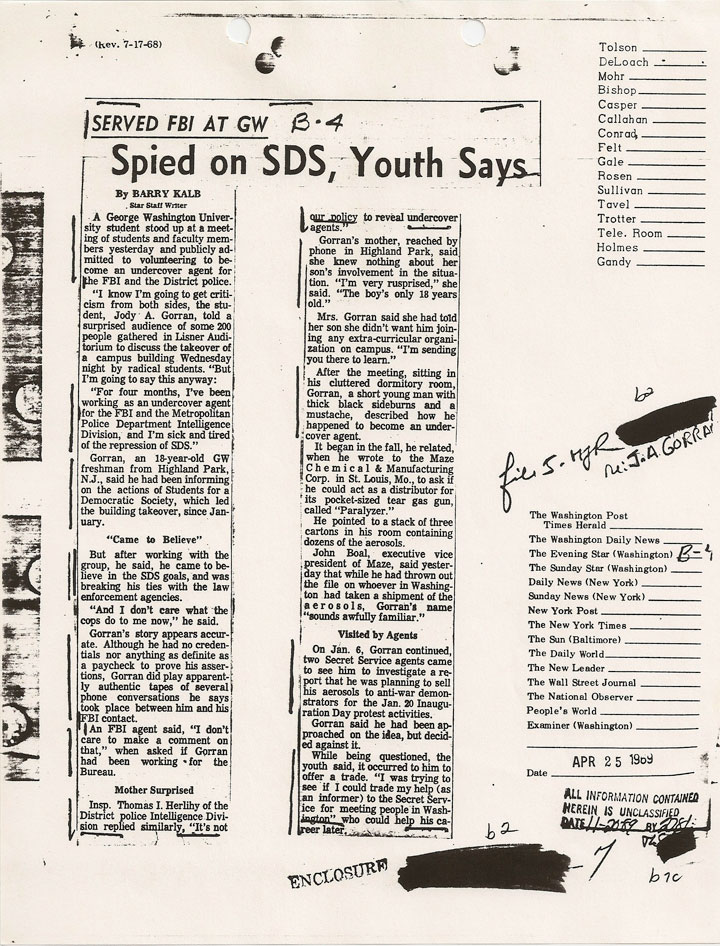

As an ambitious George Washington University student during the Vietnam War, Jody Gorran came to share John Steinbeck’s dim view of J. Edgar Hoover. Becoming an undercover operative for the Federal Bureau of Investigation and posing as a member of Students for a Democratic Society led to a personal crisis of conscience, changing his mind about politics and altering his plans for a government career. An avid Steinbeck reader, he relates his education in the turbulent politics of the Vietnam War era, explaining how he became involved with the FBI and why he risked reprisal by extricating himself from the agency following an accidental George Washington University building takeover that caused injury and led to punishment. His account, published here in his own words with photos he supplied, provides fresh insights into a divisive period in the life of America, John Steinbeck, and a college freshman on the front line of domestic dissent. The parallels with Steinbeck’s life and times are striking, and the lessons Jody learned still apply.—Ed.

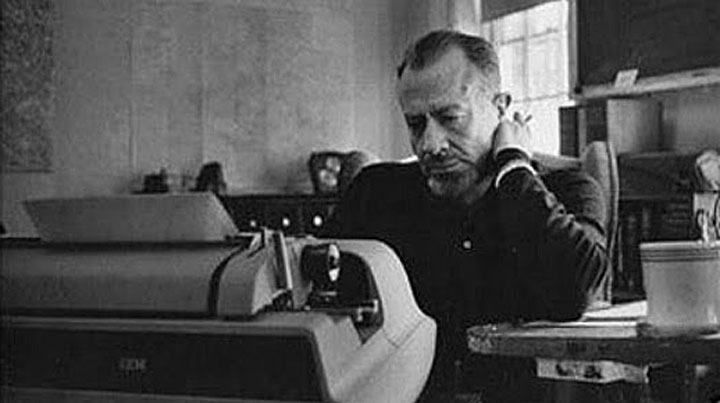

Readers familiar with John Steinbeck’s life already know that the federal government snooped on American citizens at home long before 9/11. The Federal Bureau of Investigation opened a file on Steinbeck as early as 1942, annoying the controversial author and motivating his letter to a highly placed contact in the Roosevelt administration complaining about J. Edgar Hoover. As dramatized in Steinbeck’s published fiction and noted in his private correspondence, city police departments around the country were also poking into people’s lives, even in his hometown of Salinas. Military intelligence agencies had long noses, too—one reason Steinbeck didn’t get the commission he hoped for when the U.S. entered World War II. America’s security-state apparatus expanded exponentially in the cold war that followed , a period of aggressive domestic surveillance justified in the name of anti-Communism. When John Steinbeck died, I was a college freshman. Four months after his death, I got caught in the same net that snagged him three decades earlier. This is the story of my education.

George Washington University: The Place To Be in 1968

As an 18-year-old student at George Washington University, I wound up playing an unplanned part in the national security excesses of the Vietnam War protest era. American campuses became covert battlefields where J. Edgar Hoover’s agency waged undercover war on dissidents, often in complicity with local police. Like Steinbeck, my parents had been young adults during the Great Depression and trusted government, encouraging me to focus on academics so I could get well-paying federal job with a pension. As I considered various colleges, I thought majoring in political science made sense for someone, like me, contemplating a foreign service career with the State Department. At the time, Washington, D.C., seemed like the best place to be for my particular goal. What happened after I enrolled at George Washington University changed my politics and my career plans.

What happened after I enrolled at George Washington University changed my politics and my career plans.

Before registering for the fall 1968 term, I spent the summer working as a Fuller Brush Man in my hometown of Highland Park, New Jersey. Unlike Steinbeck, I enjoyed door-to-door sales, which earned me money and got my entrepreneurial juices flowing. While reading a direct marketing sales magazine one day, I noticed an ad offering distributorships for a new product called the Paralyzer, a pocket-sized tear gas canister designed for personal protection. D.C.—a high-crime city where riots occurred—seemed like a natural market. In my ambitious 18-year-old mind, who better than me to supply the demand for security anyone could carry in a pocket or purse? I scrapped together the money I needed to secure start-up inventory and started my side business, unaware that I’d set off a chain reaction that would alter the course of my life at and after George Washington Unversity.

Coming-of-Age Politics in the Anti-Vietnam War Era

Despite my ambition, I arrived at George Washington University in the fall of 1968 apathetic about partisan politics, pretty typical for kids with my background. Though a certain percentage chose to attend colleges in the District of Columbia because they were engaged by current events, this was long before the internet, social media, and cable TV brought daily news into every den and dorm room. Even with the Vietnam War raging and John Steinbeck’s unpopular friend Lyndon Johnson on his way out as president, having a student deferment served to insulate most college students from what their government was doing in Southeast Asia—let alone on campus.

Even with the Vietnam War raging and John Steinbeck’s unpopular friend Lyndon Johnson on his way out as president, having a student deferment served to insulate most college students.

But I became curious about what was taking place in the nation’s capital on Election Day that November. The George Washington University chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, also known as SDS, had tried to stage a march from the Lincoln Memorial to Lafayette Park across from the White House to protest the election, a close contest between Hubert Humphrey and a man Steinbeck hated—Richard Nixon. Anti-Vietnam War protests had disrupted Humphrey’s nominating convention in Chicago, where Mayor Daley’s police overreacted in force and may have cost his party the election. Tension was high when Election Day protestors at George Washington University were denied a permit to demonstrate by D.C. authorities. They marched anyway until they were forced back onto campus by the Metropolitan Police Department.

Tension was high when Election Day protestors at George Washington University were denied a permit to demonstrate by D.C. authorities.

I was standing on George Washington University’s urban campus, made up of intersecting city streets, when I noticed a crowd of demonstrators headed my way and crossed the street to get a better look—just as the police moved in. Suddenly, a cop ran by swinging a club, hitting me on the back and forcing me to the ground. One of many bystanders who were attacked without warning, I was less than happy about the behavior of the police. When I heard about an SDS meeting being called to discuss what occurred, I was curious to find out what had happened to others and decided to go. I knew next to nothing about Students for a Democratic Society, but I learned soon enough.

I knew next to nothing about Students for a Democratic Society, but I learned soon enough.

Students for a Democratic Society started at the University of Michigan in 1960 with a political manifesto known as the Port Huron Statement, formally adopted at the organization’s first convention in 1962. Drafted by Tom Hayden, a University of California anti-Vietnam War activist, it faulted the political system of the United States for failing to achieve international peace and critiqued Cold War foreign policy, particularly America’s super-sized military arsenal and the very real threat of nuclear war. Vietnam War opposition aside, SDS was pretty close to John Steinbeck’s thinking on domestic issues, including racial discrimination, economic inequality, and the big corporations, big unions, and political parties that benefited most from the accelerating arms race.

Students for a Democratic Society started at the University of Michigan in 1960 with a political manifesto draft by Tom Hayden, a University of California anti-Vietnam War activist.

It has been suggested that Steinbeck sent his sons to fight in the Vietnam War out of loyalty to LBJ, whose First Lady was a childhood friend of Steinbeck’s wife. I don’t know enough to comment. But when Johnson escalated the conflict in February 1965 by bombing North Vietnam and sending American troops to fight the Viet Cong in South Vietnam, SDS chapters on American campuses staged small, localized demonstrations against the Vietnam War, coordinated through the group’s central office in New York, which led in organizing the national anti-Vietnam War march on Washington in April that year. By then there were 52 SDS chapters in the United States, and America’s mainstream media began to pay attention. The youthful New Left—misunderstood and distrusted by most adults of John Steinbeck’s generation—had arrived. The Vietnam War-era draft provided a particularly potent calling card for student recruitment, and college protests spread. Back in Washington the government’s most experienced Communist-hunter, J. Edgar Hoover, was watching. The Federal Bureau of Investigation may have lost interest in John Steinbeck by 1965, but a hot wind was rising on campuses from California to New York, and J. Edgar Hoover knew how to stop a storm.

The youthful New Left—misunderstood and distrusted by most adults of John Steinbeck’s generation—had arrived.

Protests became more and more militant throughout the winter and spring of 1967. Actions aimed at Army recruiters on college campuses accelerated, and demonstrations against Dow Chemical Company—the manufacturer of Napalm—added a combustible element to the anti-Vietnam War mix. New Left Notes, the newspaper of the movement, was creating a sense of coherence and solidarity among local SDS chapters; when Madison riot police injured and arrested students protesting the presence of Dow employee-recruiters at the University of Wisconsin in October, the growing national network was electrified. Four days later, 100,000 people marched on the Pentagon, with hundreds of protestors injured and arrested. Nighttime raids on local draft offices became more common, and a million students boycotted classes on April 26, 1968. The shutdown at Columbia University in New York—known, simply, as the Revolt—received major media attention, and SDS became a household word. Although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, the stage was set for my personal political awakening.

My First Date with the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The day after the November 1968 election, someone I happened to remember seeing at the George Washington University SDS meeting must have recognized me as a guy who had pocket-sized tear gas canisters for sale, because a few weeks later he approached me with an offer. Would I be willing to sell him a large quantity of Paralyzers from my supply? As a budding businessman, I liked the idea because sales so far had been less than robust. Because I was now paying attention to political news, I also understood clearly from our conversation that the proposed purchase was directly related to the presidential inauguration—an event I suspect contributed to the death of John Steinbeck, a passionate anti-Nixonite, six weeks after Richard Nixon’s election. In what lawyers like to call an abundance of caution, I declined the deal, a rational decision that failed to save me from J. Edgar Hoover’s unwanted attention. Someone was already watching me.

I also understood clearly from our conversation that the proposed purchase was directly related to the presidential inauguration—an event I suspect contributed to the death of John Steinbeck, a passionate anti-Nixonite.

On the evening of January 8, 1969, there was a knock at my George Washington University dorm room door. The two men standing in the hallway identified themselves as Secret Service agents and said they’d gotten word that I was going to sell my tear gas canisters to demonstrators for non-peaceful use during Nixon’s swearing-in. When I explained that I turned down the guy from the SDS meeting who had approached me, they suggested that they hold on to my inventory for safe keeping until after the inauguration. Sensing that they didn’t trust me, I agreed—and I was worried. I came to George Washington University because I wanted a government career, and as they talked all I could think about was how I could prove my loyalty and keep the incident from ruining my future. John Steinbeck had goaded J. Edgar Hoover in a well-written letter. I was afraid of the man, so I just improvised. Was there any way I could prove my loyalty, I asked? Maybe, they said. The Secret Service didn’t need campus operatives . . . but the Federal Bureau of Investigation did.

How J. Edgar Hoover Kept Up with the Joneses at the CIA

So why would the Federal Bureau of Investigation consider someone like me useful? Readers of Brian Kannard’s book Steinbeck: Citizen Spy are aware of the government’s secret surveillance program called COINTELPRO, a clunky acronym for an elusive enterprise created in 1956 to ferret out suspected Communists, including Steinbeck’s friends and (from J. Edgar Hoover’s point of view, no doubt) Steinbeck himself. Though the acronym stands for “Counterintelligence Program,” the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s targets were not enemy spies but American citizens considered radical and worth eliminating through exposure, harassment, and prosecution for real or imagined political crimes—an FBI version of the kind of covert action for which the CIA, its rival agency, was criticized by writers like Gore Vidal.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s targets were not enemy spies but American citizens considered radical and worth eliminating through exposure, harassment, and prosecution.

Under the new program, Hoover’s headquarters instructed its field offices to propose schemes to “misdirect, discredit, disrupt and otherwise neutralize” individuals and groups considered dangerous to the status quo. Close coordination with local police and prosecutors was encouraged, but ultimate authority rested with top FBI officials in Washington, who demanded assurance that “there is no possibility of embarrassment to the Bureau.” More than 2,000 individual actions were officially approved. The methods used, uncovered long after the fact, confirm John Steinbeck’s suspicions about J. Edgar Hoover’s dark side:

- Agents and undercover informers were to discredit and disrupt, not simply spy on subjects of interest.

- Agents and police collaborators were to wage psychological war on approved targets through bogus publications, forged correspondence, and anonymous letters and calls.

- Harassment, intimidation and violence, eviction, job-loss, black bag operations and break-ins, vandalism, grand jury subpoenas, false arrests, frame-ups, and physical violence were to be threatened, instigated, or executed to intimidate activists, mislead the public, and disrupt protest plans. When challenged, officials were to deny, conceal, or fabricate legal pretexts for their actions.

J. Edgar Hoover Needs You: You’re in the Agency Now!

Of course I knew none of this at the time. As I pondered my approach to the Federal Bureau of Investigation the day after my visit from the Secret Service, I saw a notice about that evening’s SDS meeting at George Washington University. I attended out of curiosity, my first regular SDS meeting. The guest speaker was a Mr. Al McSurly, who made statements advocating the overthrow of the government of the United States, though not violently. His comments didn’t sit well with me, and I thought that telling the FBI about the meeting and the speaker could serve as my ticket to J. Edgar Hoover’s forgiveness. The following day I walked down to the FBI’s Washington Field Office, known as the WFO—then located in the Old Post Office Building. There I was escorted to a small office where I spoke with an agent and signed on. From that point forward events moved quickly.

I thought that telling the FBI about the meeting and the speaker could serve as my ticket to J. Edgar Hoover’s forgiveness.

I was asked to join the George Washington University SDS chapter, as well as the national group, and to provide written reports on the activities of the organization and its members. I would be paid $15 for each report, plus expenses. While I could generally choose the subjects of my reports based on discussions with my FBI handler, from time to time I would receive instructions about specific subjects or events that J. Edgar Hoover’s people wanted me to research or attend and report. I was provided with a direct telephone number where I could leave messages for my handler, along with a code number for reporting. I was told that the Federal Bureau of Investigation would perform a field background check on me—just as they had on John Steinbeck, without warning, three decades earlier.

I was told that the Federal Bureau of Investigation would perform a field background check on me—just as they had on John Steinbeck, without warning, three decades earlier.

My first assignment was to attend a regional SDS conference being held across town at American University. There I learned that the national organization had decided in December to stay out of inauguration demonstration events in January. Instead, a group called Mobilization Against the War in Viet Nam would handle these activities. I also met the Washington Regional SDS coordinator, a 24-year old named Cathy Wilkerson who I later learned was a major focus of agency attention. To me Cathy seemed an unlikely agitator, the child of parents in Connecticut and a graduate of Swarthmore College. I was even younger than she was, but I was learning fast—though not, I soon discovered, fast enough to avoid the crisis of conscience that would derail my relationship with the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

To me Cathy seemed an unlikely agitator, the child of parents in Connecticut and a graduate of Swarthmore College.

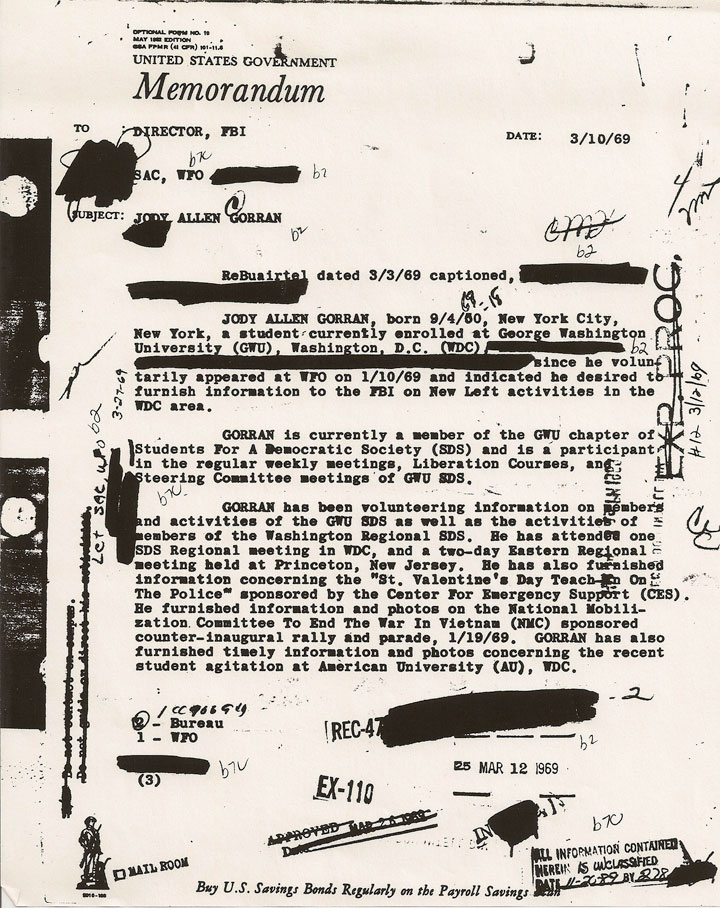

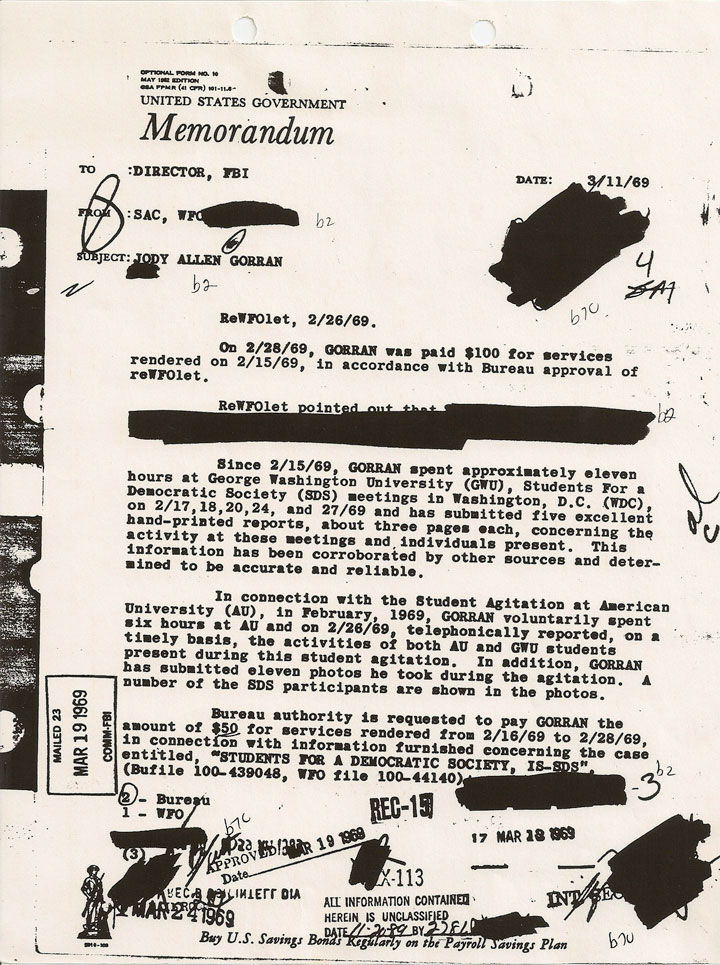

The first 60 days of my undercover activities were cataloged by the FBI in documents obtained under a Freedom of Information Request I filed years later. Here is what my handler wrote about my work:

Gorran has voluntarily expended an estimated 69 hours in attending SDS meetings and the National Mobilization Committee counter inaugural activity. He has furnished 29 pertinent photographs, and his written reports have totaled approximately 44 pages.

Gorran has been volunteering information on members and activities of the GW SDS as well as the activities of members of the Washington Regional SDS. He has attended one SDS Regional Meeting in Wash DC and a two-day Eastern Regional meeting held at Princeton, NJ. Gorran has also furnished timely information and photos concerning the recent student agitation at American University.

On 2/15/69, Gorran, at risk to his personal safety, voluntarily furnished a vast amount of invaluable information, not otherwise obtainable, in connection with the Center for Emergency Support sponsored St Valentine’s Day Teach-In on the Police. This information included over 200 names of individuals of interest to the Bureau, with current addresses and organizational affiliations. Many of these names and organizational affiliations were not previously known to the WFO. Also included in this information was data concerning 28 financial disbursements made by the organization, the current financial status of the organization and miscellaneous notes, memos and material relating to this organization.

What my handler failed to mention was that this information was obtained through an illegal black bag operation—in this case, a literal black bag. Though compliance was voluntary on my part, I had been tasked to snatch a briefcase containing the information from its location at the rear of the crowded room in which the meeting was being held. It was simple. I got up, walked purposefully to the back of the room, carefully picked up the briefcase, exited the building, and headed for my George Washington University dorm two blocks away. My heart was in my throat the whole way, but apparently no one saw me; the next day I took a cab downtown to the Greyhound Bus Station as instructed, placed the purloined briefcase in a locker, then delivered the key to my handler. I was given a $100 bonus for my boldness.

As my file shows, J. Edgar Hoover’s boys were pleased with me—for the moment:

Also according to the FBI, the information reported by Gorran has been current, detailed and accurate. His reports are considered very good to excellent. Of unusual value was Gorran’s detailed 12 page report and copies of proposals and materials concerning the SDS Eastern Regional Meeting at Princeton, NJ. The information furnished to date by Gorran has been corroborated by other sources and is considered to be 95 to 100 percent accurate.

In my interaction with my handler, I noticed that the more information I could provide regarding Cathy Wilkerson, the happier he seemed to be. But the bulk of my reporting concerned proposals that filtered down from the SDS national office through the Washington regional group. The implications of the protest plan called “Smash the Military in the Schools” would have appalled an egalitarian like Steinbeck. It exposed the problems encountered by campus military recruiters and the tracking systems supposedly used to ensure that African-American and Puerto-Rican students were shoved into the armed forces or toward menial civilian jobs when they finished high school.

Visit Cuba, Courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

As part of my undercover job for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, I helped develop and distribute flyers in an effort to stop recruiting by Sikorsky and other military-equipment suppliers for the Vietnam War, and I warned fellow students, as instructed, about CIA recruitment activity at George Washington University. But there was also a chance to travel. At one point my handler asked if I would like to visit Cuba during summer vacation, something SDS members seemed to find particularly appealing. Though the agency would pay my way, it couldn’t offer protection if I got arrested. Despite prodding, I declined.

At one point my handler asked if I would like to visit Cuba during summer vacation, something SDS members seemed to find particularly appealing.

Later I was assigned by my handler to tape-record a George Washington University speech by Hans Dietrich Wolff, a member of West Germany’s version of SDS. Wolff’s main point—one that probably flattered as much as it frightened the Feds—was that a revolution in any country had to be coupled with a revolt in the United States. For some reason, Wolff’s plan to solicit funds in the U.S. to support German SDS activities appeared to interest the agency more than his vision of world revolution. Though he didn’t pass the hat at George Washington University, he did sell posters showing Karl Marx with a caption that read (in German) “Everyone talks about the weather. We don’t.”

For some reason, Wolff’s plan to solicit funds in the U.S. to support German SDS activities appeared to interest the agency more than this vision of world revolution.

I still couldn’t shake my concern about the FBI’s interest in sending me to Cuba. Frankly, I thought the CIA was a safer bet if push came to shove on foreign soil. After making an extra copy of my recording of Wolff’s speech, I took a cab to the CIA in Langley, Virginia, where I was admitted and handed over my tape. During my debriefing interview, the possibility of my going to Cuba with CIA oversight was discussed. Due to my doubts about the FBI, there I sat, offering myself up as a CIA asset, though the agency never followed through. Incredibly, I was able to walk into CIA headquarters unimpeded, though I needed a pass to leave. Whether or not John Steinbeck was ever involved with the agency, as Brian Kannard believes, I think he would have appreciated the irony.

Policemen, Polygons, and Vietnam War Protest Pressure

In mid-March of 1969 my handler informed me that due to agency cutbacks I was being asked to transfer my efforts from the Federal Bureau of Investigation to D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department Intelligence Division—another irony worthy of a writer like Steinbeck. Where the FBI gave me $15 per report on an a la carte basis, the MPD would pay me a flat fee of $60 a week.

As noted, the FBI had a close relationship with the MPD, and my former handler would still have access to the fruits of my labors. This time, however, instead of a number I was given the code name Polygon, a term meaning “many-sided figure”—Irony #3, since the head of the D.C. police intelligence division was a chip off J. Edgar Hoover’s shoulder who insisted that anyone opposed to the Vietnam War was subversive. This overreach resulted in surveillance of peaceful anti-Vietnam War organizations with a commitment to nonviolence, a bitter reminder that the civil rights leaders Martin Luther King, Jr. was targeted for character assassination by J. Edgar Hoover long before being killed by James Earl Ray in Memphis. Other big-city police departments were also active in surveillance against the New Left at the time, including New York, Los Angeles, and—of course—Richard Daley’s Chicago.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was targeted for character assassination by J. Edgar Hoover long before being killed by James Earl Ray Memphis.

Although the FBI always seemed to want to know everything, the Washington PD was only interested in clear and present danger. As a result my work became a matter of diminishing returns, despite the higher pay. While undercover I was never privy to the identities of other government operatives planted in local and regional SDS groups, though I sensed they were there. But legitimate SDS members tended to speculate amongst themselves about various individuals, especially non-students who hung around, showed up for meetings, and participated in campus demonstrations without having a known connection to George Washington University. I suspected that several of these characters were fellow agents: two in particular—a man named Smiley, who dressed poorly and claimed to be an army veteran, and a bearded guy I called Dave whom no one seemed to know much about. Smiley and Dave appeared to be friends.

CONUS Once Shame on You; CONUS Twice Shame on Us

Because of Smiley’s supposed army service, I wondered if he might be working for military intelligence, which I later learned had expanded domestic surveillance activities significantly in the years following the failure of John Steinbeck’s friend Adlai Stevenson, a liberal, to win the presidency. These activities accelerated in the administrations of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon as a result of perceived threats posed by the civil rights movement, anti-Vietnam War feelings, and urban riots. By 1965 a new intelligence command had been established at Fort Holabird, Maryland, to coordinate the work of counterintelligence agents at army commands throughout the United States., preparing daily civil disturbance situation reports on right-wing extremists, civil rights activists, and Vietnam War dissidents.

By 1965 a new intelligence command had been established at Fort Holabird, Maryland, to coordinate the work of counterintelligence agents at army commands throughout the United States.

By 1966 the U.S. Army’s Intelligence Command at Fort Holabird had broadened its civilian surveillance, including operations that clearly violated regulations and probably occurred without the approval of senior commanders. In 1968 it was renamed Continental United States Intelligence (CONUS Intel), producing daily computerized field reports on civilians assembled by more than 1,000 plainclothes agents who monitored civil rights and antiwar organizations, infiltrated radical groups such as SDS, and engaged in provocative and illegal acts to discredit protest efforts—just like the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The extent of CONUS Intel domestic military surveillance activities became the center of controversy when a former intelligence officer exposed its operations in the January 1970 issue of Washington Monthly magazine. Thirty years earlier John Steinbeck’s chance for a wartime commission had been sandbagged by the same military mentality, another case of “John was there first” in the troubling history of domestic spying on U.S. citizens.

Barbarians at the George Washington University Gate

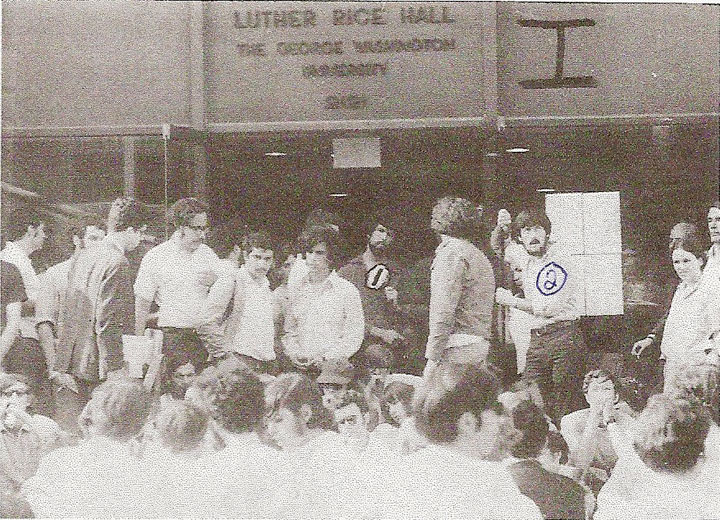

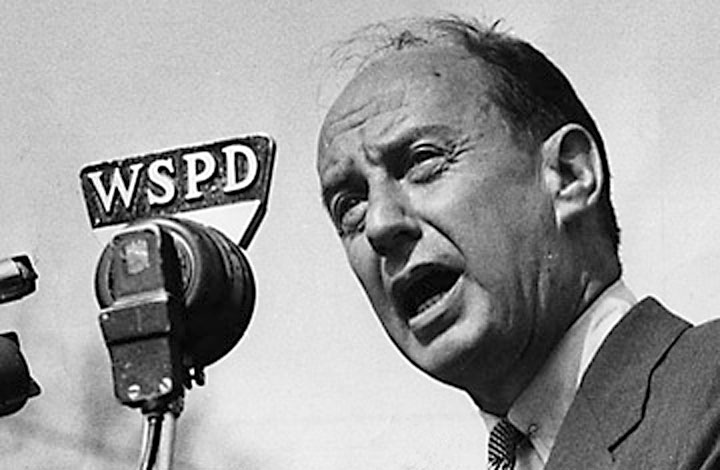

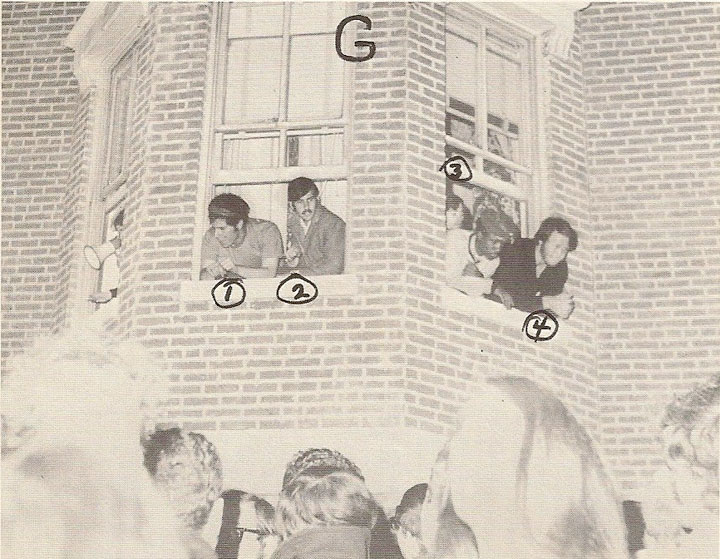

Things were heating up for both SDS and me at George Washington University on the evening of April 23, 1969, when the Black Panther film Pig Power was shown along with the Columbia University takeover documentary, Revolt. The well-publicized event drew a crowd of about 200 SDS members and non-members. Cathy Wilkerson, the subject of Federal Bureau of Investigation interest from Connecticut, was in the crowd, and so was I. At approximately 10 p.m. the leader of the local SDS chapter stood up and announced, “Our brothers have taken a building. Let’s join them!” And we were off to nearby Maury Hall, the George Washington University building that housed the Sino-Soviet Institute, a think tank with presumed military ties.

At approximately 10 p.m. the leader of the local SDS chapter stood up and announced, ‘Our brothers have taken a building. Let’s join them!’

A group of 20-30 attendees proceeded down G Street past a row of George Washington University fraternity houses, where a claque of jeering frat boys decided to follow us to Maury Hall. When I reached the building the front door was open and a few people were standing around in the lobby near a cleaning lady with keys to the locked interior offices loosely tied around her waist. I remember that someone said we couldn’t ask her to give us the keys because it might get her into trouble while somebody else gently unsnapped her key ring and led us on. Fights broke out between the frat-boy hangers-on and student protesters who had just walked in. As the violence escalated, the SDS chapter leader’s wife was hit repeatedly, sustaining a serious blow to the head.

As the violence escalated, the SDS chapter leader’s wife was hit repeatedly, sustaining a serious blow to the head.

Soon the dean of students arrived and announced that the front doors would be locked for 15 minutes with us inside, then reopened so we could leave safely—clearly a command, not a request. The SDS leader with the injured wife suggested that we had made our point by peacefully entering the building and should comply with the dean’s order: the bullies outside were thirsty for blood, and we’d be smart to exit the building while we still had the chance. Others present, egged on by the mysterious Smiley, were adamant about remaining. A vote was taken about whether or not to leave Maury Hall. The chapter leader lost and we stayed.

A vote was taken about whether or not to leave Maury Hall. The chapter leader lost and we stayed.

In the end, the SDS barricade of Maury Hall at George Washington University was as unplanned as my involvement with the Federal Bureau of Investigation—something, as Steinbeck would say, that happened. The Greek-letter warriors outside were already climbing the fire escape to get in, literal barbarians at the gate. So we built barricades, using desks, chairs, and bookcases that we moved from fortified floors to those with exposed windows. I knew how the Romans must have felt with Goths and Vandals at the gate: when I looked out from the second floor window the crowd below was chanting jump, jump, jump!—Steinbeck’s Mob Man incarnate. I was disgusted with the goons, but I was also disgusted with myself. Furniture had been damaged, people had been hurt, and the occupiers had done nothing to deserve this. I wanted out—out of Maury Hall, out of J. Edgar Hoover’s paranoia, and (ultimately, I discovered) out of George Washington University.

The Greek-letter warriors outside were already climbing the fire escape to get in, literal barbarians at the gate.

At 3:00 a.m. the school’s vice president said we had to leave immediately or be subject to violating a federal court injunction that could expose us to penalties for contempt, including jail without trial. Within 30 minutes we had abandoned Maury Hall. Later that day several hundred George Washington University students and faculty members assembled in Lisner Auditorium to discuss the takeover. Some expressed support, others disapproval. I had already made up my mind when walked to the lectern to speak. “I know I’m going to get criticism from both sides,” I said. “But I have a confession to make. For the last four months I’ve been working as an undercover agent for the FBI and the Metropolitan Police Department Intelligence Division. I’m sick and tired of the repression of SDS. And I don’t care what the cops do to me now!”

At 3:00 a.m. the school’s vice president said we had to leave immediately or be subject to violating a federal court injunction that could expose us to penalties for contempt, including jail without trial.

My confession made quite an impression, and it wasn’t friendly. As I was escorted from the building by a group of SDSers, I saw Dave with the beard making a fast exit through a side door. I realized then that he was what I had suspected—another undercover operative. Like a character in a Steinbeck strike story, I seriously wondered if I was going to be killed. Instead, I was debriefed by Cathy Wilkerson, who obviously knew that she was the subject of ongoing surveillance by J. Edgar Hoover & Company. I made it clear to her and those listening that I was done with both sides of this conflict and wanted out. But not everyone was done with me.

Leaving the Federal Bureau of Investigation? Get a Lawyer

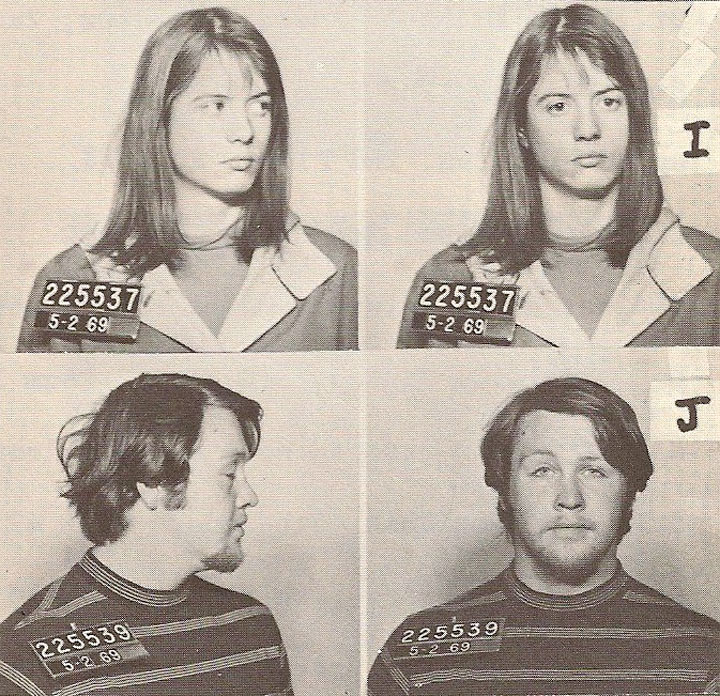

A week later, 14 other George Washington University students and I were charged with unlawfully seizing Maury Hall. The Federal Bureau of Investigation couldn’t and wouldn’t help me. Fortunately I had a good lawyer—myself. Though I was always paid in cash and had no check stubs to prove that I was working as an agency operative, the tape-recordings I had made of numerous phone conversations with my FBI and MPD handlers spoke volumes. I played the tapes at my hearing and George Washington University dropped the charges.

A week later, 14 other George Washington University students and I were charged with unlawfully seizing Maury Hall. The Federal Bureau of Investigation couldn’t and wouldn’t help me. Fortunately I had a good lawyer—myself.

In July the U.S. House of Representatives Internal Security Committee investigating SDS activities on college campuses subpoenaed me. (This was the successor to the House Un-American Activities Committee, the body that failed to call Steinbeck as a witness in its investigations of suspected writers and artists a decade earlier.) In my testimony I made it clear that anything I testified to had already been disclosed as part of my undercover work for the federal government. The Congressmen present appeared to know the answers to the questions they were asking, and it all struck me as little more than a public show. The only thing they seemed seriously concerned about was that I not go into too much detail about the FBI, something I couldn’t do and answer their questions honestly. (Did John Steinbeck also have information about government surveillance that Congress didn’t want to hear?)

Did John Steinbeck also have information about government surveillance that Congress didn’t want to hear?

Although I eventually transferred to Rutgers, I returned in the fall for another year at George Washington University. During an October afternoon walk off campus, I happened to find myself near the Washington Monument watching an anti-Vietnam War demonstration by a Mobilization Against the War group. Off to the right I noticed a uniformed army officer conferring with two men in J. Edgar Hoover attire—white shirts, dark suits, conservative ties, and trench coats. One was easy to recognize. It was Smiley, the SDS member who was so adamant about staying in Maury Hall despite the danger. I had never seen him dressed so well. Now I knew why: Smiley was an agent provocateur who encouraged people to do destructive things that they hadn’t planned on doing.

The second man was a harder to identify, but I managed. It was Dave with the beard, clean-shaven and spiffy. I went up to him and said, “Hi Dave!—or whatever your name is. I always thought you and Smiley might be army intelligence and now I know for sure.” (I’m no Steinbeck and I don’t plan to write a story of betrayal featuring these characters, but someone probably should.)

After the Fall: Cathy Wilkerson’s Unhappy Ending

On the morning of March 6, 1970, Cathy Wilkerson stumbled onto 11th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village in tatters, bleeding, her clothes shredded. Her father’s townhouse at 18 West 11th Street had just been blown to pieces, killing three members of the Weathermen group who were building bombs in the basement. After the explosion Cathy went underground for a decade, surrendering in 1980 and serving less than a year in prison. The only other survivor, Kathy Boudin, was captured in 1981 during the robbery of a Brink’s truck in which three people were murdered.

After the explosion Cathy went underground for a decade, surrendering in 1980 and serving less than a year in prison.

Following the takeover of Maury Hall in 1969, Cathy had been arrested and prohibited from setting foot on the campus of George Washington University, or any other college in the District of Columbia. Precluded from continuing the campus organizing she so enjoyed, she joined the Weathermen, the explosive group that evolved out of SDS two months after Maury Hall and adopted much more violent tactics.

J. Edgar Hoover, John Steinbeck, and America’s Aftermath

During the 1960s and 70s, COINTELPRO, CONUS, and other government surveillance programs distorted the public’s view of radical groups in a way that helped, as intended, to isolate them and to de-legitimize lawful political expression in America. The efforts of the Federal Bureau of Investigation in particular reinforced and exacerbated the weaknesses of these groups, making it difficult for sincere but inexperienced activists to learn from their mistakes and build solid, durable organizations opposed to the Vietnam War and domestic government overreach. Covert manipulation by undercover operatives, media manipulation, and agents provocateurs like Smiley eventually helped to push committed and seasoned activists such as Cathy Wilkerson to abandon grassroots organizing and join groups like the Weathermen, further isolating them and depriving peaceful protest movements of experienced leadership.

During the 1960s and 70s, COINTELPRO, CONUS, and other government surveillance programs distorted the public’s view of radical groups in a way that helped, as intended, to isolate them and to de-legitimize lawful political expression in America.

COINTELPRO succeeded in convincing some of its victims to blame themselves for problems the government created, leaving a legacy of cynicism and despair that has worsened with time. By operating covertly and illegally, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and police and army intelligence professionals were able to severely weaken domestic political opposition—a phenomenon unimaginable to John Steinbeck when he wrote his letter complaining about J. Edgar Hoover in 1942. It really happened, and for a brief period in the late 1960s I was a part.

COINTELPRO succeeded in convincing some of its victims to blame themselves for problems the government created, leaving a legacy of cynicism and despair that has worsened with time.

As for John Steinbeck’s alleged involvement with the CIA, I asked someone in a position to know more than most people about this controversial question. Commenting for background only, a former Deputy Director for Intelligence of the CIA explained the possibilities to me:

“There were two ways a U.S. civilian might be used for intelligence gathering by the agency. He might be actively tasked by the operations directorate to obtain specific information or take a more passive role by simply being debriefed regarding any information he might have inadvertently obtained during his travels.”

The former DDI added that, though he had absolutely no information about John Steinbeck, “the latter situation would have probably been the more likely scenario for Steinbeck if he had been providing any intelligence for the agency, but the former more active role could not be excluded.”